I’m writing this fresh from the book launch at Heide of Modern Love: The Lives of John and Sunday Reed, and yet another familiar roam through the old Heide farmhouse where much of these lives played out and where is now hosted an accompanying exhibition of the same name.

This first biography of the Reeds, by Heide curators Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, is the second in a 2015 biographical trilogy that covers four central weavers in the fabric of Australian Modernism: John and Sunday Reed, Sidney Nolan (Nancy Underhill’s Sidney Nolan: a Life) and Max Harris (Betty Snowden’s Max Harris: with reason, without rhyme). Each a first biography, the books have taken a surprisingly long time to be written since the deaths of their subjects: thirty four, twenty three and twenty years respectively.

Much has been written of the Reeds. Indeed few essays into modernist Australian art and culture ignore them and their influence. Rather than larding this post with the common regurgitation of a reviewed book’s content, readers looking for a quick snapshot of Heide and the Reeds can find it here.

What distinguishes Lesley Harding’s and Kendrah Morgan’s new book from its predecessors, and in a sense advantages it, is that it is the Reeds’ first biography. It paints their whole lives, rather than giving fragmentary accounts of their interests, passions and acquaintances from a particular perspective. No earlier work benefits from being cast in the broad prism of biography.

Perhaps it is best to begin, in a manner of speaking, by putting the sex to bed.

The most casual of Heide cognoscenti would be well aware of the hints and innuendo of sexual allure, intrigue and mystique linked with the Reeds and their place in the artistic sun at Heidelberg. With Modern Love, these hints and innuendo are unclothed and appear as naked fact. This however is amply backed by the authors’ scholarship, by their access to previously inaccessible primary sources and by disclosures to them of hitherto unknown information by Reed contemporaries.

Moreover, the sexual relationships mentioned in Modern Love, even if relatively few of them were completely unknown, are many and varied. Here is a mud map of sorts.

Marital: Sunday and her first husband Leonard Quinn, Sunday and John, Sidney Nolan and his first wife Elizabeth Paterson, Nolan and his second wife John’s sister Cynthia Reed, Nolan and his third wife Mary Boyd Perceval, artist Sam Atyeo and artist Moya Dyring, artist Albert Tucker and artist Joy Hester; Joy Hester and artist Gray Smith.

Extra-marital: Sunday and Sam Atyeo, John and Moya Dyring, Sam Atyeo and Cynthia Reed, Sunday and conductor Bernard Heinze, Cynthia Reed and Bernard Heinze, Sunday and journalist Peter Bellew, Sunday and journalist Michael Keon, Sunday and Nolan, Nolan and Pauline McCarthy, Nolan and psychoanalyst/educator Janet Nield, Nolan and artist Alannah Coleman, Nolan and Reg Ellery’s wife Mancell Kirby, Nolan and Joy Hester, Nolan and Cynthia Reed.

Same sex: Sunday with the unnamed wife of a well-known musician (and with Nolan participating), Sunday and Joy Hester, Nolan and Barrie Reid, Barrie Reid and Charles Osborne, Barrie Reid and Philip Jones.

Bisexual: Barrie Reid who boasted of pleasuring Melbourne’s most beautiful boy and girl both, Sweeney Reed.

Voyeuristic: John on Sunday with Sam Atyeo, with Michael Keon and with Nolan.

There you have it, or most of it, and although you’ll hardly read it in much greater detail in the book, at first blush it might all seem to demand Venn diagrams and Org Charts. However it seems quite different to Tim Burstall’s description of nearby Eltham as a ‘sexual madhouse’ and to the comment by Hilary McPhee, editor of his recently published 1954 diary, that “sex for Tim is a major focus, and it sometimes seems as if his sense of himself is measured by his ejaculations. His manipulations of women and his misogyny will outrage some readers, as perhaps will Betty’s complicity at times.”1

Life at Heide would not seem to have been like Burstall’s at Eltham – the difference, I suggest, being of more substance than Nolan’s much later line that sex at Heide was “made discrete by morning tea.”2

To date I’ve read only one review, and it fails to resist disproportionate emphasis on the sexual aspect of the story. It would indeed be a shame if Modern Love became best known as the book lifting the lid on what really went on “out there at Heide” – wink wink, nudge nudge. The book is about much more than this, as were the Reeds and as are the authors.

I’ve now known Kendrah Morgan and Lesley Harding for ten years since I first loaned ephemera for a Heide exhibition, and then in 2009 Kendrah and I co-curated the exhibition Ern Malley: the Hoax and Beyond. Sex sells, but when they told me the title Modern Love was their own choice rather than the publisher’s, I was confident any revelations of sexual relationships the book might contain (and there were many that might be told) would be quite subservient to a much broader authorial brush painting the Reeds’ love for the Modern. Sexual love, its tempests, trials, trappings and tribulations (and there were many tribulations for the main players) would be but one part of this tale.

And that is how it is with this quite remarkable book. Modern Love tells of a great and enduring love – but one which, for all its modernity, proved to be destructive.

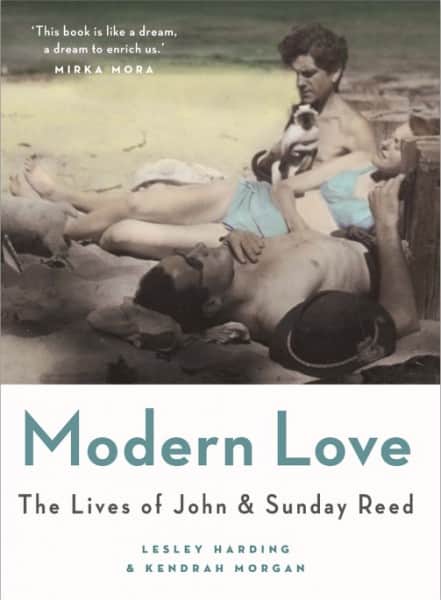

Turning first to the cover with its little known photo – a real gem. Photo-shopped from the original black and white to give Sunday’s bathers her favourite pale blue hue, it mirrors the Reeds’ story as does no other image: on the beach at Point Lonsdale with John in the distance looking troubled, remote and nursing a pet of more Simian than Siamese appearance; Sunday reclining in the certain reveries of loves received; and beside her, foremost, a nonchalant Nolan being …. well, being Nolan.

John Reed (holding Min the cat), Sunday Reed and Sidney Nolan, Point Lonsdale, c. 1945, photographer John Sinclair, SLV

Here is the ménage à trois par excellence – but one destined not to last. Quintessentially capturing a relationship that would blight all their lives forever, I suspect this photo is from around New Year 1946. Perhaps John’s hat in the foreground, looking quite incongruous at the seaside, is a Fayrefield Fedora.3

It all brings to mind Johnnie Fedora and Alice Bluebonnet, the evocative song of lost love from that same year, which, in the context of the cover photo, can be parodied thus:

Johnnie Fedora met Sunday Blue bathers

Next to Nolan on the Point Lonsdale shore,

‘Twas love at first sight and all promised one night

They’d be sweethearts for evermore.

Nolan would serenade Sunday

Tooralay, tooralie, tooraloo

He said that he dreamed of a someday

When their ménage à trois could be two.

But Johnnie Fedora and Sunday Blue bathers

Were soon alone on Point Lonsdale’s shore,

‘Cause Nolan so fraught by the plight he was caught by,

Took off and was seen never more.

“Oh Nolan, my Nolan” sighed Sunday Blue bathers

“I always will love both of you.

Dear No, stop your dreaming; our Kellys are gleaming;

My true love will see us all through.”

But it was not to be.

As Nolan would say almost fifty years later: “she wanted it both ways you see …. . Everyone wanted something that was impossible, which is natural for human beings …. but they don’t usually get it.”4

However, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Modern Love is about much more than just the Reeds and Sidney Nolan. First and foremost it is the story of John and Sunday and of their love for each other, second of their love of modern art, and third their love of those they saw as gifted to create and foster it – these last two so often incompatable and causing conflict.

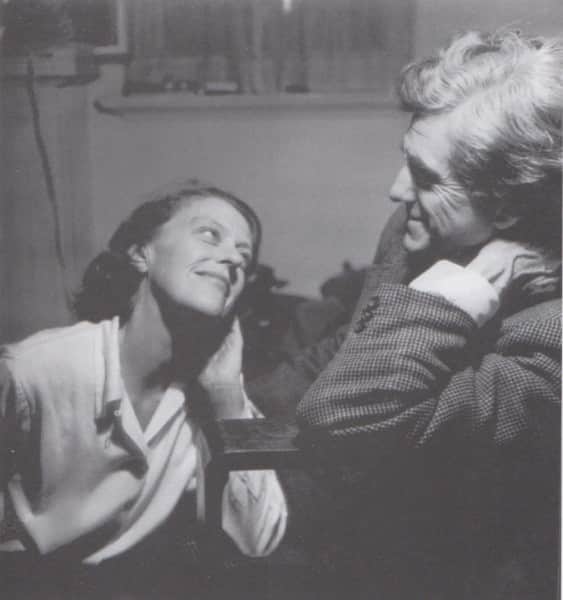

John and Sunday, 1962, photographer Nadine Amadio

The authors are uniquely placed to write on the Reeds. Curators at Heide for a combined total of twenty five years, they have been treading the boards as it were of old Heide (Heide I in modern parlance), the concrete floor of the ‘new’ McGlashan-Everist house down the hill (Heide II) and the gardens in between and around, passing by the old scar or ‘Canoe’ tree (Yingabeal) at the foot of which John and Sunday’s ashes have rested now for more than thirty years. Their two previous co-authored books, Sunday’s Kitchen in 2010 and Sunday’s Garden in 2012, build on catalogue essays for the several Heide-centered exhibitions they’ve curated.

From MUP’s Meigunyah Press, Modern Love presents quite beautifully with over forty colour images of art works, and almost 150 contemporary black and white photographs. Mirka Mora, artist and close friend of the Reeds from the late 1940s, says “this book is like a dream, a dream to enrich us” and that “it is a tour de force, they have come alive again.” Art historian Richard Haese, whose landmark 1981 Rebels and Precursors first drew general public attention to Heide and the Reeds, suggests “Modern Love is a rich and satisfyingly detailed account of the remarkable lives of John and Sunday Reed , the champions of Australian radical modernism, and of the extraordinary array of artists and writers who came to stay and work at Heide.”

Our taste for Modern Love is whetted with the Prologue’s opening sentence “Sunday Baillieu was worldly but damaged, and John Reed was just coming into his own when they met in 1930.” They marry and the prologue, no more than an amuse-bouche, concludes with young painter Sam Atyeo joining them “in their first experiment with an alternative model of relationship, one that would come to define the terms of their marriage: what the French discretely call a ménage à trois.”

The chapter headings allow us to chart Modern Love’s course: Beginnings, Awakening, The Enchanted Domain, Modern Times, Angry Penguins, Love and War, Paradise Lost, Exodus, La Vie Bohème, A Child on the High Seas, A Gallery to Be Lived In, Agony in the Garden, and the Epilogue: Despair Has Wings. And that is sufficient primer for this review – those with some knowledge of the story will glean what lies ahead, while those breaking new ground are surely tempted to learn more.

Those reading this book will discover tantalising glimpses into hitherto unknown or unpublished material: a draft biography of Albert Tucker written by Michael Keon; transcripts of Michael Keon interviewed by Richard Haese in 1981; transcripts of Barrie Reed interviewed by Richard Haese in 1981, 1984 and 1985; a transcript of John Sinclair interviewed by Richard Haese in 1982. It is to be hoped that this material, now retrieved from its attic repository, will remain available for further research. Other fresh insights come from the authors’ more recent interviews with the likes of Jean Langley, Pauline McCarthy, Susie Brunton and Pamela McIntosh, all Reed contemporaries going back as much as seventy years.

John Reed with Sweeney and Gray Smith near the Heart Garden at Heide, c. 1949, photographer John Sinclair, SLV

Modern Love was launched on a glorious spring day in the side garden at Heide, seen in the 1949 photo above. The Heart Garden, planted by Sunday to mark Nolan’s flight from her, is clearly evident. When this photo was unearthed several years ago, her little garden was replanted, and at the launch I sat beside it, by chance sharing the very spot with the authors of the Reed, Nolan and Harris biographies.

Reflecting on the occasion now as I finish writing this review, I wonder what John and Sunday would have made of it all. They would have eschewed the public spotlight I’m sure. The milling throng stayed largely within the garden however, and perhaps there were but few who, when leaving, visited the ancient Canoe tree where their ashes lie – barely fifty meters to the right of the heart-shaped tribute.

I looked too at the faces in the crowd and recognised some who would have been in the garden many years ago on other occasions, or whose parents certainly could have been there in its hey day and perhaps on differing sides of the many entanglements playing out. Suddenly the never-ending debate about the Reeds seemed quite secondary to the actuality of their real legacy – this place in which we were standing, the art on its walls, and the art that found expression within those walls.

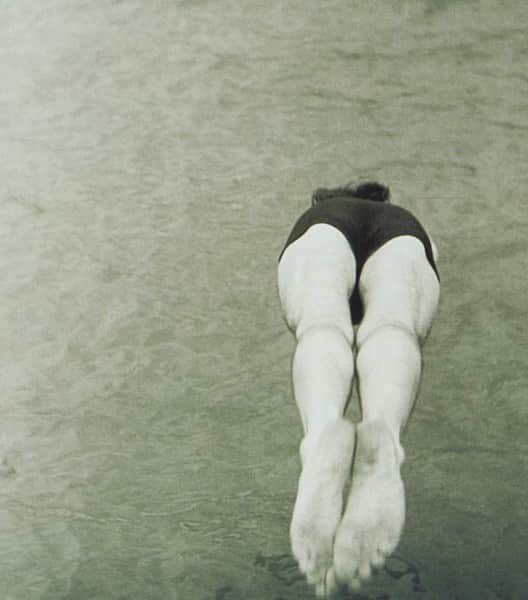

Bert Tucker’s 1942 photograph of Nolan about to make waves diving into the Yarra below old Heide seems apposite. Love, creativity, inspiration, sex, sadness; these are but the splashes and ripples on the steam – big splashes and ripples sometimes to be sure, but as another artist said in paint of Heidelberg almost fifty years before the Reeds discovered their haven, ‘still glides the stream and shall forever glide.’5

Sidney Nolan diving into Yarra River at Heide, c. 1942, photographer Albert Tucker

Richard Haese says that Modern Love is a story “of immense achievement and loss in equal measure.” Too true – and not for the Reeds alone – others in their circles were hostage to the winds of fortune blowing across the Heide waters.

Barbara Blackman, whose first husband Charles was a favourite at Heide in the 1950s but who herself had an uneasy relationship with Sunday, tells of an occasion in the early 1980s celebrating the reality of Heide Park and Art Gallery (as the Heide Museum of Modern Art was originally known.) A nautical toast was proposed: “God bless Heide and all who sailed in her” – to which Barbara added sotto voce, “and all who walked the plank.”6

She tells of the Reeds accusing Charles of stealing the transparencies of Nolan’s Kelly paintings, and failing to apologise for the accusation when it was shown to be false – an incident bringing to mind their accusations against both Micheal Keon and Bert Tucker of the theft of money. They had their detractors and were, it is probably fair to say, both loved and detested, perhaps also in equal measure. Even their staunchest supporters agreed that for many, the Reeds’ support came at a cost.

Perhaps Max Harris summed it up best in a letter he wrote after a less than successful visit to Heide in 1955. “…. the strange inexplicable tragedy of Heide, which aims so high, is that the pattern is ever thus. Why aims so pure and loving should produce a pattern of tension and withdrawal in the world, I do not surely know. …. Perhaps, in down-to-earth psychological terms you desire too actively to establish a deep human involvement. Perhaps people who live easily and seemingly superficially are wise. They let the involvement grow if it will, easily, and of itself.”7

Harris’ is a more measured view than this from Charles Osborne, never a fan, who wrote of them “They were certainly very generous with their money, their time and their interest, but they seemed to want one’s soul in return. …. she was a sad, unfulfilled woman and, perhaps in spite of herself, extraordinarily destructive. People around her seemed to die.”8

This is both fatuous and unfair – vintage Osborne. Death is around us all. Nevertheless, it is not unreasonable to observe that suicides were perhaps more prevalent in their circle than in the general public – the period from the mid 1970s to the early 1980s in particular. John and Cynthia’s uncle, thwarted in love by family obligations, suicided in London at an early age. Cynthia, Nolan’s wife, did likewise in November 1976 – a scant few months after John and Sunday’s close friend Leslie Stack. Their adopted son Sweeney, Joy Hester’s son, took his life in March 1979, then John his on 5 December 1981, and Sunday hers just ten days later.

Sweeney Reed’s death focusses the mind on what Modern Love tells us, and on what it doesn’t. It tells John and Sunday’s story with brilliance, leading us through the magic, the turmoil, the intricacies, the sorrows and despairs of their lives. But it leads us only tantalisingly toward the yet to be fully delineated relationship with Nolan, and barely hints (though much more so than any earlier account) at the tragic, truly tragic, tale of Sweeney – surely a biography awaiting sympathetic scholarship and telling.

John, Sunday and Sweeney Reed, in the garden at Heide, c. 1952

These stories remain to be written, either as fact or fiction. I hesitate, but not overly, to draw attention to my own play, The Ménage at Soria Moria, a dramatic monologue portraying the Reeds’ lives in the context of Sunday’s relationship with John and Nolan. Posted on this website in November 2014 and whilst a fiction based closely on fact, some things I thought to be imaginings (John’s voyeurism for example) materialise as fact in Modern Love.

Soria Moria ends with Nolan visiting Heide in 1982, barely six weeks after Sunday’s death. It has been thirty five years since he left. With his wife Mary, he comes to see the inaugural Heide exhibition – his complete first series Kelly paintings.

When checking dates of the visit with Maudie Palmer, Heide’s first Director, I showed her Soria Moria. Two things in particular she said in response have stayed with me, and neatly wrap up this Review: “Women can love more than one man at once!” and “be kind to Sunday’s memory, she made an extraordinary and extremely under acknowledged contribution to Australian art.” Today she added “Our cultural lives would be so much poorer if it were not for them.” Agreed.9

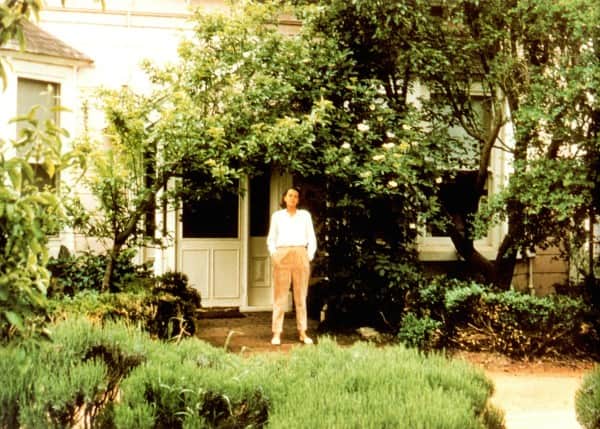

Let this photo by Bert Tucker pay tribute.

Sunday Reed by the front door of Heide. Mid-1940s. Photo by Albert Tucker

On finishing Modern Love, I felt – and this from someone steeped in the Heide legend – the exhilaration of having been in step, for some way, along the path of a worthy quest. Schmalzy, I know, but it brought to mind these last lines of the musical Camelot.

Don’t let it be forgot

That once there was a spot

For one brief shining moment that was known

As Camelot.

Tintagel, Hyannis Port …. Heidelberg? Well, why not draw a long bow!

If legends of great Australian art are of interest, and a touch of ‘happily-ever-aftering’ in a ‘congenial spot’ appeals, then you must read this book.

MORE REVIEWS

END NOTES

- Memoirs of a Young Bastard: The diaries of Tim Burstall, November 1953 to December 1954, Ed. Hilary McPhee, 2012, The Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, p. xvii.

- Nolan’s poem “The Return,” from his derisory 1971 Paradise Garden, contains this line with reference to a brief drunken visit to Heide by Sam Atyeo towards the end of the war.

The failed lover from Paris came

Drunk as drunk could be

he crawled into bed

and then there were three.

The pricks between the sheets

were stiff as Death

but made discreet

by morning tea.

- Upon leaving school Nolan worked for several years in the 1930s at Fayrefield Hat Company, Abbotsford.

- See Sidney Nolan interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 5 April 1991 on this website.

- Arthur Streeton’s 1890 painting Still glides the stream, and shall forever glide looks from Mount Eagle (Eaglemont) over the Yarra valley towards Heide.

- Barbara Blackman, conversation with the writer, 2 October 2015.

- Max Harris, letter to John Reed, 10 September 1955, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 10, File 2.

- Charles Osborne, Giving it Away: memoirs of an uncivil servant, Secker and Warburg, London, 1986, p. 41. My copy of this book is Osborne’s presentation copy to Barrie Reid, his lover from their 1940 Brisbane days. He has written “Barrie. Here it is – the greatest piece of Australian fiction since On Our Selection. Love. Charlie.

- Maudie Palmer, emails to the writer, 12 January 2015 and 7 October 2015.

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

‘But it leads us only tantalisingly toward the yet to be fully delineated relationship with Nolan……’

Nolan’s subsequent behaviour awaits explanation. Love lost seems inadequate and I suspect a pathology that will need a splendid psychiatric opinion. Or better, perhaps a mythological Sunday devoured his soul.