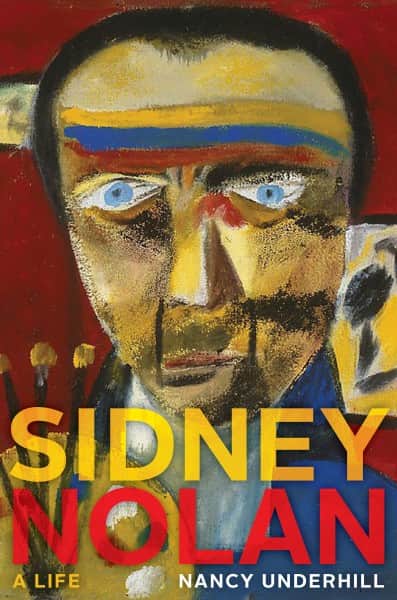

Dr Nancy Underhill’s new Nolan biography Sidney Nolan: a life is very good.

The first biography to really look at his life as a whole1 rather than in segments bearing on a particular theme or exhibition, it will become a classic standard text. And deservedly so.

Nancy Underhill, “Sidney Nolan: a life”, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015

Having regard to Sidney Nolan’s much avowed Irishness, I once worked out that he was just two days old on the first anniversary of Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising. This new biography of Australia’s best known painter went on-line exactly 99 years from the day the last of the Rising leaders were shot by the British.

Sidney Nolan: a life reveals to surprised Nolan devotees, long drip-fed Nolan’s Irish ancestry and his policeman grandfather’s pursuit of Ned Kelly, that Sid’s much vaunted Irishness had its roots in Protestant Northern Ireland rather than in the tribal Catholicism of the likes of the Kelly clan. Moreover his grandfather Bill Nolan was not a regular member of the Victorian Police Force, but rather was taken on “especially for duty re Outlaws” and absconded from duty after 18 months – a fact which Underhill sets beside Nolan himself going AWL from the Australian Army in WW2.

This Celtic revisionism of Nolan is up front and prominent, indeed it is all of Chapter 2 in this new biography, just released by NewSouth Publishing and to be launched at Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne this weekend.

And there are other things about Nolan found here in print for the first time.

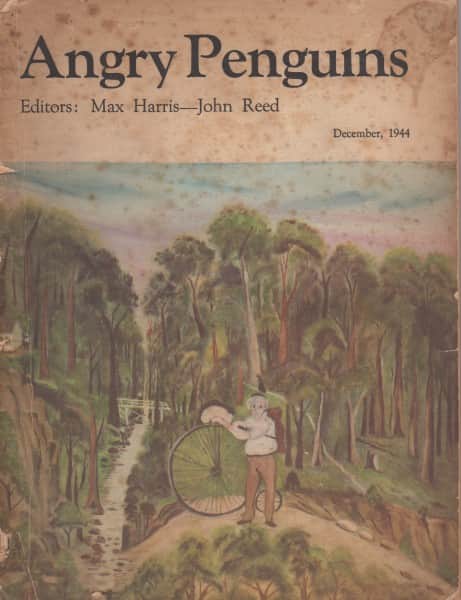

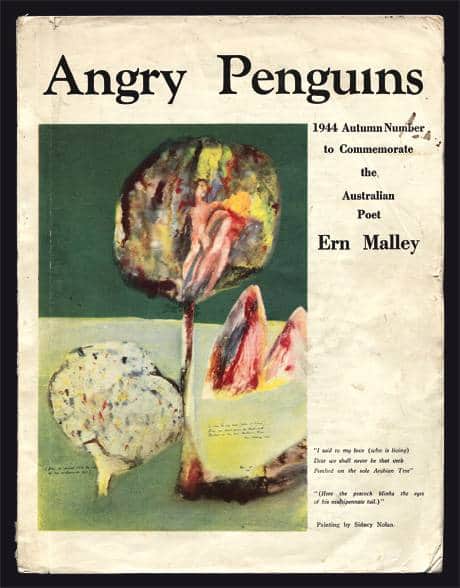

Among them that Nolan probably had a hand, along with Bert Tucker, in what was most likely another hoax hard on the heels of Ern Malley – the “H.D.” or Professor Tipper affair involving naive daubings which surfaced in Melbourne in the mid 1940s and were published in Angry Penguins.

“Angry Penguins” No. 7, December 1944, with cover painting “by H.D. an Unknown Australian Primitive”

Underhill also argues that Nolan’s boss Vernon Jones at Fayrefield Hats, where the artist worked for several years in the 1930s, remains an underestimated influence, as does Nolan’s training there as a commercial artist. “In Australia, insufficient attention was paid to how advertising energised contemporary avant-garde imagery.”2 She compellingly argues how this period influenced him far more than has been acknowledged, and informed much of the “calculated shock” character of the more iconic and landmark works among his early paintings.

Aside from the Irish question and the H.D. story, the avid Nolan enthusiast or researcher may find relatively few revelations shedding light on hitherto unknown facets of his life. However the author’s take on the man and his art and on the influences which shaped them, often runs counter to conventional wisdom. Witness for example the influence of his advertising experience mentioned above, the role of friends and patrons like Alistair McAlpine, Elwyn (Jack) Lynn and Stuart Cooper, and the views of his siblings and their families. A hitherto unknown source, at least to me, is an unpublished family memoir Sidney Nolan: a brush with life by Nolan’s brother-in-law Laurie Sweet.

But what sets the book quite apart from anything previously written about Nolan, is not the depth and scope of the sources relied upon, nor is it the various views as to what or who may have been of greater or lesser influence. Rather it is that in Sidney Nolan: a life, precisely because it sets out to tell the story of a life rather than to focus only on certain aspects or periods of that life, we finally have for Nolan a coherent narrative, without gaps, spanning his 76 years.

The book traces the well known story. It tells of his major works, his alter-egos (Ern Malley as much as Ned Kelly), his travels, his loves, his fallings-out – the whole panoply – but often tells it with embellishments that add a human dimension to what hitherto may have been little more than a bare fact. Thus whilst it was known that Nolan and his first wife Elizabeth (Betty) Paterson briefly ran a pie shop in Melbourne’s Lonsdale Street and lived in upstairs digs, we learn here how they were financed into this venture with ₤50 from Sid’s dad (who would only give the money to Betty) and how to parental consternation they simply walked out on the investment when keen on the idea of moving to Sydney – a decision prompted by their 1940 visit when Nolan was commissioned by Serge Lifar to design the set for the Ballets Russes opera Icare.

A Montreal friend recently sent the photo below. I irreverently imagine that perhaps Ern Malley didn’t return to Sydney in 1942 to die at the same age as Ned Kelly, Keats and as Nolan was then, but rather, mindful of the Sid & Betty Pie Emporium, took the idea with him to Canada and made his fortune selling pies instead of poems!

Ned Kelly pie of the day, Montreal, 2015

Underhill writes with great clarity, succinctness, and candour. She cuts quickly to the chase and is able to present complex matters in simple, often refreshingly colloquial language. Thus commenting on Nolan’s own throwaway line “I’m just a lurking larrikin on standby” she comments “Too right, but Nolan is more complex than that.”3 As for the ubiquitous Kellys of his latter years she concludes “…. during the 1980s …. Ned Kelly was still there, but in more relaxed roles such as private references among friends, a witty moment, or a private cash cow.”4 She mentions that “Lord Vestey bought two outback landscapes to remind him of the large chunk he actually owned”5 and speaking of a Stephen Spender catalogue Introduction observes “the result is a bob each way ….”6

She opts for what one might term ‘common sense’ or ‘most likely’ answers and opinions. Thus she opines of “an Australian painting style, as opposed to just Australian subjects” that it is “surely a pursuit as aesthetically misguided as Australian-style music, poetry, or indeed golf.”7 As to the most likely reason why artists were prone to leave Heide after a certain exposure, she proffers the simple straightforward answer “I believe the answer to a changing of the avant-garde at Heide lies more in the fact that those talented men and others simply craved independent adult lives over which they had real control.”8

The book will find wide appeal. It strikes a fine balance between the more esoteric analysis expected of an art historian and a down to earthiness which makes it readily accessible to the lay person.

No punches are pulled in calling a spade a spade when describing Nolan’s dealings – whether in business or with others. Thus we learn of Vernon Jones summing him up as having “one of those babyfaces and (he) was the biggest bluffer on earth – a liar,”9 and Max Harris’ view that “Nolan’s personality is about as open as death row at Sing Sing. He manages his life as (if) it were a one man MI5. He is not a beautiful person. Although he can suffer sporadic and painful attacks of friendship he gets over them quickly ….”10 And Harris was a friend!

Underhill too makes a number of trenchant observations – among them: “Nolan became a specialist at providing interviews and so could be his own most attentive journalist. His ability to control biographical data is amazing, with there being little or no interrogation during his lifetime.”11; “Hand in hand with his volatile and surprisingly sensitive ego, Nolan’s insatiable obsession with self promotion became evident …”12; “Obviously at war with himself, Nolan allowed his ruthless artistic ambition and his enchantment with being considered wondrous to lay waste to his marriage.”13; “In retrospect after 1976 Nolan presents as an artistic personality rather than a productive innovative artist”14 and “Nolan formed his dual persona of artist and PR machine, but by then nobody could grasp the whole Nolan and he grew comfortable with that sense of subterfuge.”15 Underhill quotes Nolan himself on what she says “could be his singular rule for life: ‘It seems a matter of twisting a situation and of acting simply and effectively within it.’”16

But neither is the biography short on plaudits. Underhill writes “…. despite admitting Nolan had a rogue, secretive facet to his personality, his colleagues all found him intellectually stimulating company who continued to intrigue and whom they genuinely still missed. For those who owned any, his art was more a memento of a friendship than a trophy hanging on their wall. What greater compliment could an artist have?”17

She also “puts paid to the view Nolan was primarily an autodidact, half grasping their (a book’s) intent and primarily keen to show off by dropping names of books and people,”18 and quoting Elijah Moshinsky from Nolan’s obituary in the Guardian we learn that “the vitality of his creative personality was something I had never come across in anyone else …. the energy that seized him, his self-criticism, his lack of pretension and his ambition to reach out to something visionary and mythic I shall never forget.”19

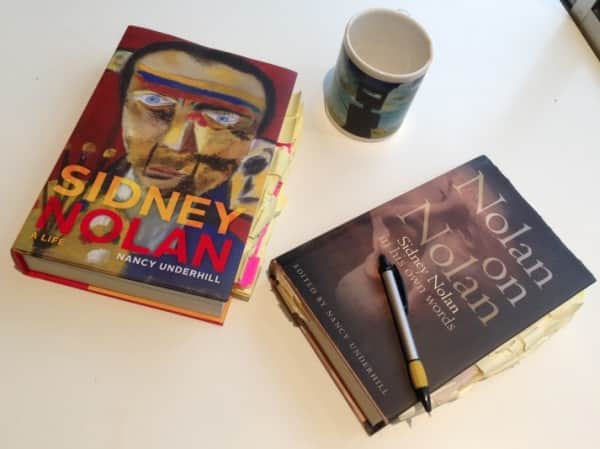

Nancy Underhill is well placed to write on Nolan. Apart from having met him several times and convincing him to sell his slate paintings to the Quensland University Museum of Art where she was Director, she collaborated with Barrie Reid (who fell in love with Nolan as a young man)20 in editing the letters of John Reed – lawyer and art patron who with his wife Sunday lived with Nolan in a ménage à trois of sorts at Heide outside Melbourne for several years in the 1940s. Underhill has also compiled Nolan on Nolan, an encyclopaedic gathering of Nolan’s writings and utterings about himself and his work, and which has become a standard text for Nolan researchers since its publication in 2007.

Dr Underhill’s two Nolan texts earmarked for research

Given her belief that “Nolan deserves a more broad-reaching critical biography informed by historical assessments”21 and that the hitherto undue emphasis of the Reed/Heide factor has been at the expense of “above all Nolan’s subsequent life and art making in Sydney and overseas, “22 on first blush it may seem odd that whilst the ten year period between 1938 when Nolan first met John Reed and March 1948 when he married Reed’s sister Cynthia accounts for less than a fifth of his adult life, discussion of this period occupies almost half the pages in the book devoted to his adult life.

Given too that Underhill writes “Somehow, at least in Melbourne, Nolan still hovers over Heide despite having lived and painted elsewhere for forty-five years.”23 those who attend this weekend’s book launch at old Heide, where Nolan lived and loved 70 years ago, might be permitted a wry chuckle.

But none of this is really surprising. Reverberations from that ten year period would profoundly affect all of them for all of their lives. It is well accepted that the Reeds never got Nolan out of their systems – there is less acceptance that he never quite managed to rid himself of them.

The book is well illustrated with 48 mainly colour plates carrying over eighty images, almost fifty of them of Nolan paintings. It is a shame though that two paintings in particular, his 1984 Self Portrait in Youth and his 1942 Wimmera, are not among them. Underhill makes interesting comparisons between the former and his 1943 Self-Portrait, and the latter and his 1942 Landscape. It would have been fascinating to have the visual comparisons alongside the textual.

The text is most comprehensive and wide reaching. Its thirty page index has no fewer than 100 references to individual Nolan paintings, 200 references to places and locations, 600 references to individual people, and even more references to subject. It is well edited – indeed in this veritable cornucopia of facts I found but one small, completely inconsequential error of fact. Some few other matters, such as whether Mrs Fraser was originally painted in 1948 or 1947, to which I incline, are matters for interperetation. The convict David Bracewell persists as Bracefell, and contrary to the official record he still rescues Eliza Fraser only to be betrayed – however, as the author correctly points out, this version of events is how Nolan understood the story.

Dr Underhill’s book is the type of Nolan biography I once dared to think I might have written. I could never have produced the good result found in Sidney Nolan: a life. Thus it seems rather mean-spirited if not impertinent, to suggest, as I later will, that something more could perhaps have been included.

Sidney Nolan: a life sets out “to explore the man who created the paintings as opposed to taking the art historian approach of using the paintings as a porthole through which to view the man. …. Nonetheless” the author continues, “I must acknowledge that the truth, or even a fair assessment of events, often remains up for grabs. Nolan planned it that way.”24

A few months ago in a preview Arise Sir Sidney for this new biography, I wrote: “The sheer volume of his works, the intensity of their themes with their national, cultural and mythological significance, his desertion from the army, his absence from Australia, his British knighthood, his unparalleled successes, his loves and his famous fallings-out – all this is the stuff of legend. And made a legend of Nolan his many cataloguers, curators, historians, gallerists and enthusiastic journalists certainly have. In all this it has seemed difficult for scholars to find the real Sidney Nolan – perhaps for the very good reason, as those who knew him well will say, that there was more than one Sid and he did his best, usually with success, to disguise them all.”

In talking of her approach of seeing the man first and then the paintings, rather than the man through the paintings, Underhill acknowledges that Nolan “made it his business to obscure what made him tick.”25 Today, twenty plus years beyond the grave – his in company with Karl Marx, Anna Mahler, Douglas Adams and Sir Ralph Richardson in London’s Highgate Cemetery – this obscuration by Nolan remains remarkably effective.

Sidney Nolan’s grave, Highgate Cemetery (East), London

The book’s subtitle Sidney Nolan: a life is well chosen. While we have Nolan’s life documented as never before with a biographical account chosen to be “warts and all,” we do not have, at least to quite the same extent, a full picture of Sidney Nolan: a person.

A virtual wellspring of latent energy can be seen to underpin many of Nolan’s early landscapes – whether it be the magical splendour in his first Kellys, the lyrical sparse lushness in his first Fraser Island paintings, the surreal vistas of his first Central Australian canvases, or the arid parchings of his drought carcasses.

Of this brief period in the history of Australian art, truly it can be said a terrible beauty is born, to borrow these words from that great Irish triumphal lament by Yeats, “Easter 1916”:

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse —

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Which brings us to the title of this review.

Much of Nolan’s painting had about it a terrible beauty. Much of his life, compellingly set out here in Sidney Nolan: a life, had about it a terrible beauty.

But what of the essence of the man …. his soul if you will. Did it have a terrible beauty …. or did it have, perhaps, a terrible torment? And what effect did that have on his oeuvre, on his influence on others, indeed on his life?

And Sidney Nolan: a life only partly answers this.

The biography acknowledges that “Serial escape routes and total immersion in a project would become hallmarks of Nolan’s approach to life. But so too in dandy fashion was his ability to appear urbane and confident while riddled with anxiety. Much of his art stemmed from what seems to have been a dark, haunted interior.”26

The reader however scarcely gets to visit this interior.

It can well be asked why one’s dark, haunted interior should be on public display? We all of us remain part mystery and this is perhaps no bad thing. Indeed Nolan, when speaking of his note book journals, said “I don’t show these notes, because I think everybody should have an area which they don’t expose.”27

However, looking at what makes an artist of Nolan’s stature tick need not be emotional voyeurism and can be considered a legitimate avenue of scholarship and enquiry – disguise it though he might.

Thus for example, there is little discussion of Nolan’s sexuality and what effect various experiences may have had on his work. We hear only of his three wives and of course his affair with Sunday Reed; nothing more than that though – other than some rather coy references: to a “friendship between Pauline (McCarthy) and Nolan (which) continued (from early 1945) until he left Melbourne in July 1947”28; to “his trip from Cairns to Magnetic Island with the beautiful painter Joy Roggenkamp”29; to a confession to John Reed “that he was fond of Joy (Hester) in a deeper way”30; and to his wife Cynthia’s suspicion of “a probable mistress.”31 Tom Rosenthal, in his 2002 monograph, describes him as “vigorously heterosexual.”32

Underhill summarily lays to rest the question whether Nolan and Barrie Reid may have briefly been lovers with the statement “I was told of this in the late 1980s when there was much intrigue about outing people, whether or not they liked it or had the right of reply. I suspect the stories of Nolan were spread after he became famous and therefore carried a certain cachet.” The book continues “a quick scan of future compatriots … (no fewer than 16 are listed) … should let the issue rest. Those who were homosexual had long-standing partners.”33 This non sequitur seems equivalent to concluding his friendships with Reid and Osborne, Britten and Pears, White and Lascaris prove the opposite.

As with many things about Nolan, the man’s own words can be the most revealing. Underhill’s 2007 book Nolan on Nolan records his comment, when interviewed at the 1990 Aldeburgh Festival and speaking of his exhibition at Aldeburgh in 1964 of two dozen paintings based on Shakespeare’s sonnets, “that was a very sombre exhibition, and it was all about a personal experience of mine, you know, rather like the Vere, the captain thing.” This reference to the homo-eroticism in Britten’s opera Billy Budd is rather unambiguous. Nolan continues “It was a hidden thing in me which I coudn’t discuss now, but it was a kind of hidden relationship, I suppose, in my life that I never discuss and – but I was able to put it into the sonnets; you know, Shakespeare was exactly it ….”34 And there follows one of those comparatively rare moments in Nolan interviews when his guard drops and he talks from the heart rather than the head.

For a biographer to pursue matters such as this is not mere idle curiosity, not salacious tittle tattle, not nudge-nudge wink-winking gossip. Nolan is probably the best known and most influential Australian painter of the 20th century and what made him tick, what made him paint, is legitimately worthy of analysis.

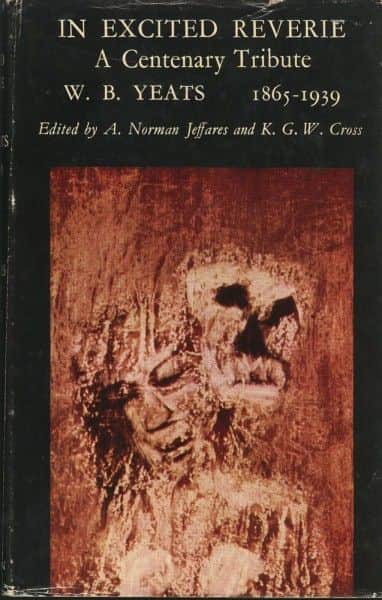

It is little known that in 1965 Nolan painted a work for the cover of In Excited Reverie, a centenary tribute to Yeats. Nolan’s image comes from his Shakespearian Sonnet series – Sonnet 71, one of a Shakespearean transformational trio in which an older lover confronts mortality and implores his younger, almost certainly male, partner to move on “Lest the wise world should look into your moan / And mock you with me after I am gone.”

ed. A. Norman Jeffares and K.G.W. Cross, “In Excited Reverie: A Centenary Tribute, W.B. Yeats 1865-1939”, Macmillan, London, 1965.

There will be a time when a future biographer of Nolan might discuss his Shakespeare Sonnet paintings. Their significance is not discussed here, not hinted at, let alone analysed – they are barely mentioned. If a painter’s oeuvre is to be examined through the prism of a life – as is the author’s stated intent here – what may be crucial aspects impacting that life need to be examined and not easily dismissed.

When that time comes, and knowing of Nolan’s life through biographies such as this, we might journey with tomorrow’s writer and discover Nolan the person. We might see for example his Sonnet paintings with new eyes, see in his invocation of Sonnet 71 arguably a self-portrait head cradled against the Simian-like skull; and ponder how it, and all the others, might reveal the person.

Interestingly, one of the contributors to In Excited Reverie was Randolph Stow who in my view plumbed Nolan’s depths better than most. Almost 20 years younger than Nolan, Mick (as he was known to friends) Stow became a close friend.35 They collaborated on a book of his poems, one of which “The Land’s Meaning” is dedicated to Nolan. It concludes with the lines:

“I was bushed for forty years.

And I came to a bloke all alone like a kurrajong tree.

And I said to him: ‘Mate – I don’t need to know your name –

let me camp in your shade, let me sleep, till the sun goes down’.”

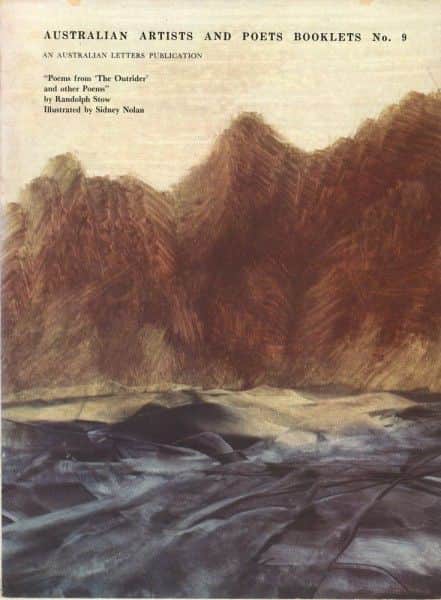

“Australian Artists and Poets Booklets No 9”, published byAustralian Letters, c 1970.

From the outset it is clear that Dr Underhill is having none of what, in its own chapter heading, she cogently terms “the myth of Heide” – her view that “in Australia, the public still tends to truncate Nolan’s life at July 1947 when he quit living with John and Sunday Reed at their home, Heide, outside Melbourne. Like Sunday, the public locks Nolan’s fame onto the group of Ned Kelly paintings he left with her. …. He became simply the man who painted Kelly.”36 She maintains “we collide with legendary life at Heide – now a veritable industry with Sidney Nolan the star attraction. …. This bias led to a focus on the importance of the Reeds which really got out of hand in the 1990s.”37

Whilst no champion of the Reeds, Underhill’s view is well balanced. She concedes that the above slant “has also blurred the serious intellectual and artistic concerns addressed by the Reeds and those around them,”38 and acknowledges that during Nolan’s time at Heide from 1941 to July 1947 “no matter how the period is assessed, it is obvious Nolan’s enormous charm and private emotional games were defined by a deep, genuine commitment to Sunday Reed and her husband.”39

However the book speaks but sparingly of the slings and arrows Nolan directed towards the Reeds in the 1960s and 1970s, and hardly at all of Heide-related demons which beset him, or indeed anything else that may have been the catalyst for his tide of invective. We read that “for Nolan, those Kellys were both his most successful public identity and the focus of private angst directed at the Reeds”40 but it is clear that Underhill understands that more than the Kellys is at play here.

She says “the Heide days in particular haunted Nolan and his notebooks and diaries are full of observations that smack of a payback, lost times and occasional wishful artistic plans,”41 and quotes Nolan writing to Kenneth Clark in 1972 about Paradise Garden: “I was really trying to get rid of some ghosts in me, not having been able to do so in paint. For the simple reason, I expect that painting is a celebration and not suitable for destruction. On reflection, this must be true of real poetry also, so my attempt in writing fails also to deal with the ghosts. Even so, I feel better for having made the attempt.”42 We read from his 13 March 1986 notebook entry “Also I will have to paint a novel, the only way I can deal with the thirties and forties in Melbourne. All this runs the risk of megalomania but I cannot forget the ruined lives.”43

Given Nolan’s obsession with the Reeds, and ‘obsession’ is not too strong a word, I wonder whether he ever made the connection that his mother’s stepfather’s name was none other than John Reid.44 He would also have been intrigued to learn, had he lived into the age of the internet, that the website for John Reed, the British poet whose well-known anti-war poem Naming of Parts Nolan almost certainly knew, is www.solearabiantree.com. The site takes its name from Nolan’s painting for the Ern Malley edition of Angry Penguins which shows him and Sunday perching verb-like and naked in the sole Arabian tree of Shakespeare’s poem The Phoenix and the Turtle.

Sidney Nolan, Arabian Tree, 1943

Cover of Angry Penguins, No 6, June 1944

In this biography we glean little of Nolan’s feelings and thoughts particularly during the late 60s and early 70s. These were years of emotional purging that saw him paint half a dozen Malley portraits in one day; saw the bitter bile of his Paradise Garden poems – unquoted here and barely rating a mention; years which saw his illustrations for McAlpine’s lavish reprint of Ern Malley’s Darkening Ecliptic – illustrations which say far more about his time at Heide, then almost 30 years distant, and far more about the effect it still had on his state of mind, than about Malley’s poems.

We learn little more than that “…. nobody really knew what went on at Heide. The illustrated poems Paradise Garden that Nolan published in 1971 are nasty exothermic paybacks that allude to voyeuristic sex.”45

Nor do we journey with the man himself when his second wife Cynthia dies. We learn a little of their increasingly difficult relationship, read again the oft told and well trodden tale of her suicide in a hotel room instead of meeting him for tea at Fortnum & Mason’s, of her telegram to him “Off to the Orkneys in small stages”, of her will’s disinheritance of him. But we don’t journey with Nolan the man along his own via Dolorosa to the Dorchester where he holed up for several days after her death – not quite the unpaying guest of his mate McAlpine, who owned the pub, as he had imagined.46

Indeed it is difficult to get any feeling as to whether there was in Nolan a hint – perhaps more than a hint, and for much of his life I would suggest – of a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief.

The book quotes Nolan’s 1943 love letter to Sunday finishing “Don’t be tired tiger toes something stays very quiet, trust I expect finally, and at the bottom such as it was is the bridge at St Kilda. N”47 Just a year after the film Casablanca was made, perhaps “the bridge at St Kilda” is Nolan’s own “we’ll always have Paris” line. His letter may well reference an intimate little 1941 painting Lovers, Luna Park. With its full moon above Catani Arch and Robe Street bunting, this painting remained on the wall of Sunday Reed’s dressing room all her life.48

“Lovers, Luna Park”, 1941, Sidney Nolan, Private collection.

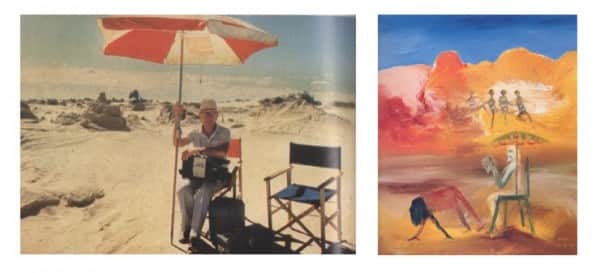

Sunday Reed’s presence for Nolan though, manifested itself quite differently. More bile, less beauty. The last of 48 plates in the book showing Nolan in 1984 on location for the shooting of the Hoyts Edgley film Burke and Wills provides a good example. Nolan used this photo as a model for his 1985 painting Robert Melville at Alice Springs. Mrs Fraser, by now well and truly his Sunday symbol, skulks by to remind all and sundry that she remained a potent presence in his psyche long after he supposedly shed himself of her in 1971 with Paradise Garden and in 1974 with Darkening Ecliptic.

left, Nolan on location for shooting of “Burke and Wills”, 1984; right, Sidney Nolan, “Robert Melville at Alice Springs”, 1985.

Nancy Underhill’s Sidney Nolan: a life is timely. Just two years short of his centenary, it is a mine of information and will deservedly be well thumbed and equally well footnoted in many a future catalogue essay.

However certain aspects of Sidney Nolan: the person remain unresolved, particularly considerations of that ‘dark, haunted interior.’ Underhill writes that “Nolan remains locked into the venerable European view that poets and artists, with their heightened sensitivity, show what others can’t quite see for themselves.”49 Is there then a key to the ‘dark, haunted interior’ to be found in poetry? Perhaps. For those willing to digress from the review of the book, this footnote looks at an outline of how an inner Nolan could be considered from the viewpoint of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Keats’ La Belle Dame Sans Merci.50

Or perhaps it is to some of Nolan’s own words in Underhill’s Nolan on Nolan we can turn for a glimpse of Nolan the person.

His poem Oz Digger51 is written in his personal diary. It recounts how “the painter Brett Whiteley asked us which we regarded the wonders of the world.”

Nolan turns to Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem Wreck of the Deutschland and thinks the wonders of the world might include Hopkins’ floating nun, who “when there … met the master of jay-blue heaven and belled fire.” But he concludes “No. It was none of these.”

It was the jar

Of my father’s cart he drove me in.

The arctic mist on the many fleeces –

Sweet heaven in pieces.

Randolph Stow’s first novel To the Islands, written when he was all of 22, memorably concludes with lines spoken by the ageing Heriot as he looks out over the Arafura Sea to the Aboriginal islands of the dead. ‘My soul,’ he whispered, over the sea-surge, ‘my soul is a strange country.’ I wonder if Stow ever revisited Heriot’s whisper with an ageing Nolan in mind.

Perhaps Nolan should have the last word. Eighteen months before he died he spoke with Michael Heyward52 who was researching his book The Ern Malley Affair. Mid-sentence, when discussing his early collages, his train of thought suddenly faltered:

SN: They were, oh just a book of old master engravings, steel engravings. And I’m very much mixed up with that now. …[very long pause] …

… Well, they’re all dead, including the dog .. [pause] .. except for .. [pause] .. such a curious feeling isn’t it..

MH: Sinclair’s still alive

SN: No he’s dead

MH: Is he dead? When did he die?

SN: About three months ago .. [long pause]

MH: Must be a strange …

SN: Mmm, it’s a strange feeling .. [long pause] .. you see cause it’s the opposite of Patrick White in a way. You know I feel [pause] ..

MH: Tremendous affection.

SN: Yeah, I feel for all … yeah .. [long pause]

TAPE ENDS

OTHER REVIEWS

http://www.sydneyreviewofbooks.com/sidney-nolan-biography-review/

END NOTES

- Brian Adam’s biography Such is Life was written several years before Nolan died.

- Nancy Underhill, Sidney Nolan: a life, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015, p. 39.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 1.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 6.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 234.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 279.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 230.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 134.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 39.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 295.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 216.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 229.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 94.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 341.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 241.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 189.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. xiv.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 215.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 318.

- Barrie Reid interviewed by Ramona Koval. (See Ramona Koval, “A Last Overland Journey,” The Age, Melbourne, 24 July 1995, p. 13.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. xii.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 97.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 255.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 3.

- Sidney Nolan: a life., p 3.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 54.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 210.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 159.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 185.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 187.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 304.

- “It is odd that the thrice-married, vigorously heterosexual Nolan, should have made so many of his female figures so asexual.” T. G. Rosenthal, Sidney Nolan, Thames & Hudson, London, 2002, p. 225.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 55.

- Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words, Viking, Melbourne, 2007, p. 358.

- On Stow’s death in 2010 Jinx Nolan posted a tribute saying “when we lived in Putney he would come and have lunch with us and then we would walk along the tow path beside the Thames. Years later he and I would meet for lunch in London.”

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. xii.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 97.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p 97.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 98.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 5.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 349.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 331.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 352.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, Footnote 9, p. 373.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 56.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 307.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 112.

- Michael Dugan, letter to David Rainey, 24 March 2005.

- Sidney Nolan: a life, p. 215.

- An inner Nolan from the viewpoint of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Keats’ La Belle Dame Sans Merci. (An extract from the essay Threads on this website.)

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that a number of events in Nolan’s life were recurring sources of guilt-laden angst surfacing from time to time. Some seem obvious: leaving his first marriage and young daughter, his desertion from the Army, his brother’s drowning on active service, and Cynthia’s suicide; others less so: his occasional reference to the ‘hidden relationship’ he associated with the Shakespearean Sonnet paintings, his dissatisfaction with a deterioration in his marriage to Cynthia, and his isolation from Australia.

These albatrosses of guilt did not fall from Nolan’s neck as they did in Coleridge’s poem with the Ancient Mariner finding redemption on seeing beauty in the creatures from the deep slime moving ‘in tracks of shining white’ with ‘flash of golden fire’ and the Mariner saying ‘a spring of love gushed from my heart, and I blessed them unaware’.

If an albatross fell from his neck, it most likely fell at the feet of Sunday Reed.

Much of Nolan’s painting is intensely personal, yet tragically the magic of all the light, all the shining white and golden fire he saw in the world, and all the beauty – a light and beauty invested in so many of his paintings – seems never for him to have released the albatross. Just as threads in a tapestry come to the surface only to disappear and reappear, so also the troubling threads in life.

It is tempting to think that most of the troubling threads surfacing in Nolan’s life he would trace back to Sunday Reed and in so-doing, time and again re-visit his personal La Belle Dame sans Merci.

The Malley poem from which Nolan derived most imagery in the 1974 Adelaide exhibition is Colloquy with John Keats and Keats’ well known poem of seductive enthralment can be seen as evocative of Nolan’s life from his early twenties. He had just ‘met a lady in the meads, full beautiful – a faery’s child, Her hair was long, her foot was light, And her eyes were wild.’

Much of the poem is redolent of Heide, especially the line ‘she took me to her elfin grot.’ Post Heide, whilst not exactly ‘alone and palely loitering,’ at times he very likely was ‘on the cold hill’s side … though the sedge is wither’d from the lake, and no birds sing.’

One can but wonder whether on occasions an inner voice whispered ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci hath thee in thrall!’

- Nolan on Nolan, p. 447.

- See Sidney Nolan interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 5 April 1991 on this website.

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

I was disappointed to find no reference to Nolan’s ‘Shakespeare Sonnets’ series (small chiaroscuro heads in burnt umber) from the mid 60s – further evidence of the artist’s intensely literary inspirations.