INTRODUCTION

.

The Ménage at Soria Moria is a fictitious two act solo performance piece exploring the relationship between Sunday Reed and Sidney Nolan. Their story, particularly the heady days at Heide during the 1940s until Nolan left in July 1947, is well documented. Soria Moria also examines the less well known degeneration in their relationship over the next 35 years. In particular it imagines what might have prompted Nolan’s increasing animosity.

The play is dedicated to the late Shelton Lea, friend, poet and person extraordinaire, who gave me books with Heide connections (including Sunday’s copy of Dylan Thomas’ Deaths and Entrances), and from whose storehouse of Heide knowledge – he was a close friend of Barrie Reid – I gleaned much. Indeed, Saturday omelettes at DeHavillands with Shel led to Sunday. It was to him I sent the first draft synopsis for Soria Moria in 2005.

Soria Moria is written for Belinda Bromilow, a dear friend and a fine actor.

Although the play follows known and acknowledged primary and secondary sources of information which are referenced in the text as endnotes,1 some central matters are entirely the creation of the writer. Sunday’s utterances are of course imagined, except for some passages borrowed from the reported words of others of the time; these are acknowledged in the endnotes.

As for imaginings, I know of no suggestion in the literature of any particular visit of Nolan and Sunday to Merthon; nor of their activities on Nolan’s 30th birthday; nor am I aware of any suggestion she wrote to him after seeing Riverbend in 1967, or wrote again in 1981 just before she died. These, and any other excursions of the imagination, are acknowledged in the endnotes. May they not be devoid of plausibility.

It is tempting to think that some catalyst in the late 1960s, other than the much vaunted issue of the first series Kelly paintings, prompted Nolan to become more proactive in denigrating the Reeds, particularly Sunday. This has been the subject of some surmise but there appears to be little concrete evidence. Accordingly, two forthcoming biographies: Sidney Nolan by Nancy Underhill (from NewSouth, scheduled for May 2015), and of the Reeds, Modern Love by Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan (from MUP, scheduled for October 2015), are eagerly awaited; as is the 2021 lifting of the embargo on Cynthia Nolan’s archive held in the National Library of Australia.

The research of many others is acknowledged, particularly Nancy Underhill, Lesley Harding, Kendrah Morgan, Janine Burke, Damian Smith and Jane Clark; all of whom have not only published so much excellent material, but have also spoken with and emailed me freely and generously.2

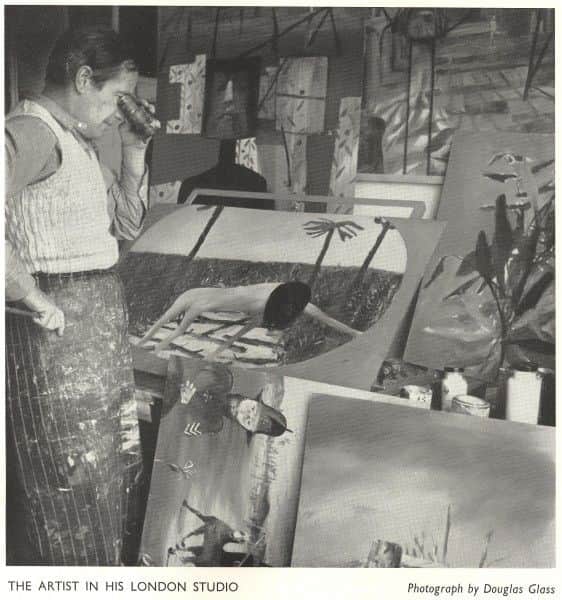

The following text is illustrated by low resolution images which would be suitable, with appropriate permissions, for a son et lumière-styled stage production. Indeed, on a fine summer’s evening one mid-December, I fondly imagine a “Sun et lumière” in the grounds at Heide where it all happened – or might have happened.

The entire text is included here for the sake of completeness. For actual performance, the text could be truncated. Similarly, whilst the embedded images may amplify the text when read on a website, there are perhaps too many for use in a performance. In the end it is the words and performance that should matter most.

.

.

.

PERSONAE (in order of mention)

.

Principal

.

SUNDAY REED. Born Melbourne, 15 October 1905; died Heide, Melbourne, 15 December 1981. Adoptive mother of Sweeney Reed. Patron of the arts and artists, muse, benefactor. Married Leonard Quinn 1926, later divorced; married John Reed 1932. Lived at Heide 1935 to 1981.

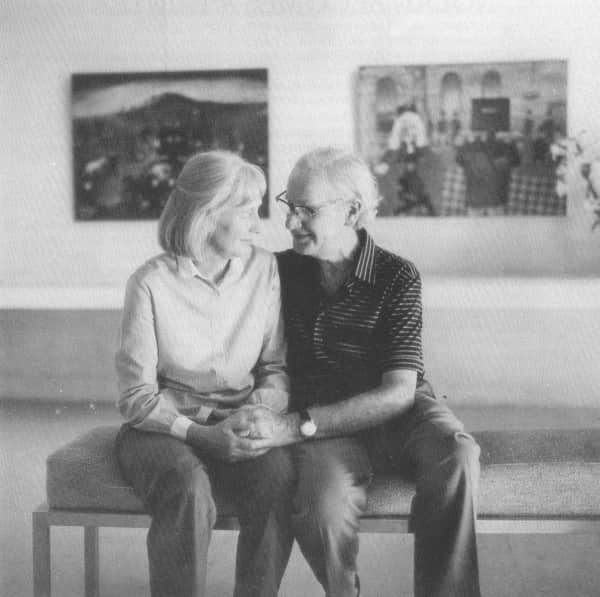

JOHN REED. Born Evandale, Tasmania, 10 December 1901; died Heide, Melbourne, 5 December 1981. Brother of Cynthia Reed. Adoptive father of Sweeney Reed. Lawyer, publisher, art critic, patron of the arts and artists, benefactor. Married Sunday Baillieu 1932. Lived at Heide 1935 to 1981.

SIDNEY NOLAN. Born Melbourne, 22 April 1917; died London, 28 November 1992. Major Australian modernist painter. Married Elizabeth Paterson 1938, later divorced. Lived at Heide in ménage à trois with John and Sunday Reed 1940-1947. Supported by them financially. Married Cynthia Reed 1948. Moved to England permanently 1951. Married Mary Perceval (née Boyd) 1978. Best known for his Ned Kelly painting series.

BARRIE REID. Born Brisbane, 8 December 1926; died Heide, Melbourne, 7 August 1995. Librarian, poet, writer, editor, literary and art critic. First met John and Sunday Reed in Brisbane 1946; first visited Heide that December. Moved to Melbourne 1951. Not related to Reeds; became their close friend and associate. Supported by them financially. Lived at Heide from 1981 to 1995.

SWEENEY REED. Born Melbourne, 4 February 1945; died Carlton, Melbourne, 24 March 1979. Son of Joy Hester. Adopted son of John and Sunday Reed. Supported by them financially. Gallery owner, publisher and poet.

.

Secondary

.

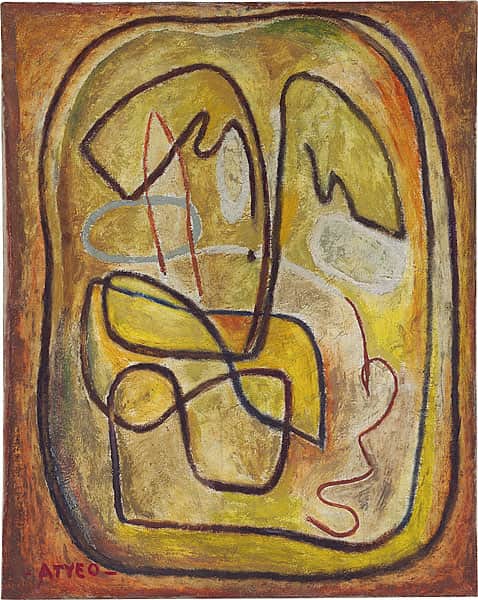

SAM ATYEO. Born Melbourne, 6 January 1910; died Vence, France, 26 May 1990. Australian modernist painter, designer, diplomat. Lover of Sunday Reed 1933-1936. Designer for Cynthia Reed’s modern interior-design shop and gallery 1934. Moved to France 1936 with long-time girlfriend Moya Dyring. Moved to Dominica 1940 where an affair with Cynthia Reed. Married Moya Dyring in Barbados 1941, later divorced. Private secretary to H V Evatt 1942-1946.

MAX HARRIS. Born Adelaide, 13 April 1921; died Adelaide, 13 January 1995. Poet, critic, columnist, editor, publisher, bookseller. Edited Angry Penguins magazine. With John and Sunday Reed established publishing house Reed & Harris 1943; Sidney Nolan a partner 1944. Close friend and associate of the Reeds and their circle at Heide, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s.

CYNTHIA NOLAN. Born Evandale, Tasmania, 18 September 1908; died London, 24 November 1976. Sister of John Reed. Known as ‘Bob’. Writer. Associated with Fred Ward’s modernist furniture shop, then opened her own interior-design shop and gallery 1933. Overseas 1935-1940. Returned to Australia 1940 via Dominica where an affair with Sam Atyeo. Stayed briefly at Heide 1941 after birth of daughter before moving to Sydney. Married Sidney Nolan 1948.

MICHAEL KEON. Born Melbourne, 19 October 1918; died Rosebud, Victoria, 22 May 2006. Art and literary critic, political journalist, international bureaucrat, author. Heide habitué in the early 1940s. His autobiography Glad Morning Again illuminates those years.

ALBERT TUCKER. Born Melbourne, 29 December 1914; died Melbourne, 23 October 1999. Major Australian modernist painter. Supposed father of Sweeney Reed. Married Joy Hester 1941, later divorced; married Barbara Bilcock 1964. Close friend and associate of the Reeds and their circle at Heide, particularly in the 1940s. Supported by them financially.

JOY HESTER. Born Melbourne, 21 August 1920; died Melbourne, 4 December 1960. Major Australian modernist painter. Mother of Sweeney Reed. Married Bert Tucker 1941, later divorced; lived with Gray Smith from 1947, they married 1959. Close friend of the Reeds and their circle at Heide. Supported by them financially.

MARY NOLAN. Born Melbourne, 8 November 1926. Youngest daughter of potters Merric and Doris Boyd; sister of major Australian modernist painter Arthur Boyd. Married painter John Perceval 1944, later divorced. Close friend of John and Sunday Reed. Married Sidney Nolan 1978. Lives in England.

.

Minor

.

DANILA VASSILIEFF (1897-1958). Russian-born; major Australian painter and sculptor. Became close friend and associate of the Reeds 1940s. Major influence on younger emerging modernist painters. Built fortress-like home “Stonygrad” at Warrandyte c 1941. Died of heart attack in library at Heide.

H V EVATT (1894-1965). Jurist, lawyer, parliamentarian, writer. Variously High Court judge, Leader of Federal Labor Party, Minister for External Affairs, first Chairman of the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, and third President of the United Nations General Assembly. In Heide circle through his wife Mary Alice, close friend of Sam Atyeo and Moya Dyring. Atyeo his private secretary 1942-1946.

JOHN SINCLAIR (1915-1991). Journalist, music critic. Close friend of Sidney Nolan and hence the Reeds. Heide habitué in the 1940s. Married Jean Langley 1952.

CLIVE TURNBULL (1906-1975). Journalist, author, poet, art critic, collector. Championed work of Sidney Nolan; purchased Stringy Bark Creek 1948.

MOYA DYRING (1909-1967). Australian painter. Close friend of Mary Alice Evatt; lover of Sam Atyeo 1930s and 1940s; thence friend of the Reeds; affair with John Reed mid 1930s. Joined Atyeo in France 1937; married Atyeo in Barbados 1941, later divorced.

FRED WARD (1900-1990). Furniture and interior designer; leading Australian modernist designer in 1930s and 1940s. Worked with Sam Atyeo and Cynthia Reed.

ELIZABETH PATERSON (1917-1993). Australian painter. Married Sidney Nolan 1938, later divorced.

REG ELLERY (1897-1955). Psychiatrist, essayist, poet, author. Friend of the Reeds and frequent visitor to Heide.

JEAN LANGLEY (b. 1926). Australian painter. Decorated pottery at Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery c. 1945. Met John Sinclair and through him the Reeds 1947. Became their close personal friend, particularly Sunday. Married John Sinclair 1952, later separated. Lives in Mt Martha, Victoria.

NADINE AMADIO (1929-2009). Author, journalist, poet, script-writer, critic. Introduced to Heide and the Reeds by Barrie Reid c. early 1950s.

SHELTON LEA (1946-2005). Poet, performer, publisher, antiquarian bookseller. Introduced to Heide and the Reeds by close friend and mentor Barrie Reid c. mid 1970s.

ALISTAIR McALPINE (1942-2014). British businessman, politician, author, avid collector. Advisor to Margaret Thatcher; friend, publisher and patron of Sidney Nolan; lover of Australia. Keen purchaser of early Nolan works.

GRAY SMITH (1919-1990). Australian painter. Lived with Joy Hester from 1947, they married 1959.

.

ACT 1

.

THE KITCHEN AT HEIDE, HOME OF JOHN AND SUNDAY REED, WITH WINDOW AND FIREPLACE TO REAR, KITCHEN TABLE AND CHAIRS CENTRE, DOOR RIGHT EXIT TO HALLWAY. DOOR LEFT EXIT TO PANTRY ETC. PAINTS, BRUSHES AND PAINTINGS ARE STACKED AGAINST THE WALL R. SUNDAY IS 41. IT IS MID DECEMBER 1946. AFTERNOON.

.

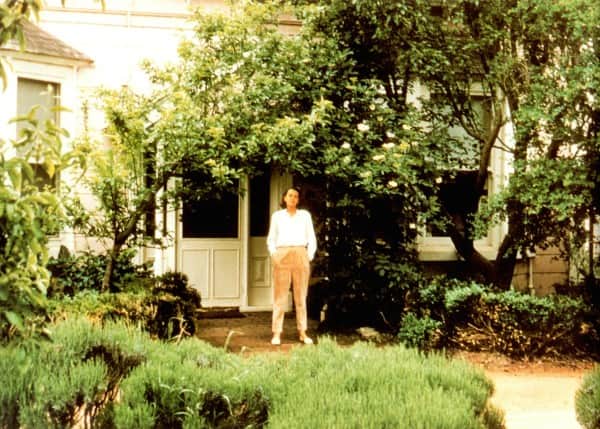

Sunday Reed by the front door of Heide. Mid-1940s. Photo by Albert Tucker

.

(Curtain rises to reveal a scrim at front of stage on which is projected the mid 1940s colour photograph of Sunday dressed in slacks standing in the garden in front of old Heide. On stage, our Sunday is similarly dressed and stands similarly with legs at ease and hands in trouser pockets. She is not visible, standing behind and hard up against her image on the scrim. The colour photo image disappears, the scrim drops away revealing a second scrim with the same image but without her figure. She turns and walks towards front of house with secateurs. Stops and cuts lavender from hedge.)

.

CALLS OUT TO STAGE L

.

Arvo tea coming up John. I’ll start it once I’ve arranged this lavender.

.

(She opens the door and walks into the house. The photo image disappears, all lights down, the second scrim is raised away and the kitchen setting lights up. Sunday enters R into kitchen when lights rise.)

.

CALLS OUT WINDOW TO JOHN

.

Nolan hasn’t rung? Hasn’t called has he? He should be back from Stonygrad3soon.

.

TO HERSELF

.

Danila was only away in Sydney for a month.

Nolan, Nolan, aah Nolan. We haven’t seen a lot of you this year, have we No. But it doesn’t matter … doesn’t matter. Or does it matter No? We probably saw more of you when you were in the army.4 Those weekends in the Wimmera were marvellous. Weren’t they No? I’d go up to Horsham with your canvases.

We’re a team, you and I Nolan, a team. Not just you and me. Johnny too. We’re all a team.

And Sam would be too if he were here. He’d still be part of us, just like he used to be. Not like that night he came here drunk though, that time he was on a UN visit for Doc Evatt.5 Supposed to be hush hush. Ha, hush hush I don’t think – you could have heard him over at Heidelberg. And his language even made me blush.

.

CALLS OUT WINDOW TO JOHN

.

I came across your letter to Max about Sammy’s visit.6

.

TO HERSELF (Reads from John’s letter)

.

“It was Sam all right, drunk because he would not have had the courage to ring if he had been sober: and so he came out and landed in the family circle, Sun and myself, Nolan and Sinclair, loud-voiced and declaiming, shitting, fucking, crapping, cock-sucking, pricking straight from America per Liberator on a secret mission, incognito and not supposed to show himself to a soul.

“And we learned all the strange Odyssey of his last nine years, all the famous figures of our world in Paris, all the brutalities of France in Spain, the personally measured 13″ tools of the West Indian negroes, the utter and complete fascism of the U.S. State Dept., the beauty of Fats Waller and Jelly Roll Morton and the broadcasting of Snozzle Durante.

“With paintings all round him he hardly noticed them – crap, shit: moments of laughter such as we don’t often have and moments of hatred culminating at 3 o’clock in the morning when he called us all bastards and strode out of the house.

“Nolan says he lost half a stone of weight that night and by this time was in a condition of white heat and marched after Sam telling him if he didn’t come back he would carry him back – Sam who isn’t used to being talked to like that and had thought Nolan an “aesthete”.

“Finally between love and despair the night ended and Sam fell asleep.

“Evatt is his evil genius, using him for his own purposes indifferent to the death of his creative faculties.

“None of us will ever forget that night, its shattering of time …. the disillusion of internationalism and the intelligentsia …. Awake the new intelligentsia! – where the bloody hell are they?”

God, your hand writing’s awful John!

…. I wonder if Sam got up to Sydney to see Bob and the girl.7

There was no need for her to live up there. Urrgh. Sydney.

.

(Shudders)

.

She could have stayed here. I wanted her to stay. I’d have helped her raise the little one …. I wanted to help … I wanted to. But she left. Bob just left me.

.

(She starts preparing scones for Arvo Tea)

.

TO OFFSTAGE

.

Johnny, remember that night Sam came back. Do you think he was jealous? Jealous. No, not Sam, Sam wasn’t jealous …. do you think Nolan was jealous? Well he shouldn’t have been – and you shouldn’t have been either.

I’ve told you that. You know I have, so often. I realise it was hard for you – but they were both here, here together. I know. I know. I didn’t want to hurt you Johnny …

.

TO HERSELF

.

Darling John, always there for me. You’ll always be there for me, won’t you Johnny?

.

TO OFFSTAGE

.

Stay there a while. The scones aren’t in yet. Be about twenty minutes. I’ll call you when they’re ready. We’ll have it in the library. It’s too hot in here.

Aah Nolan. When will you be back? Today? Please come today No.

.

TO HERSELF

.

Remember Nolan the time I showed you Merthon.8 The family was away and we drove down to Sorrento.

.

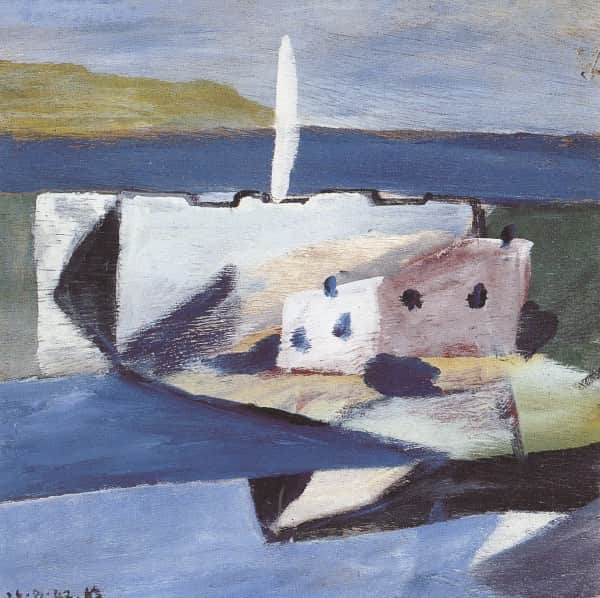

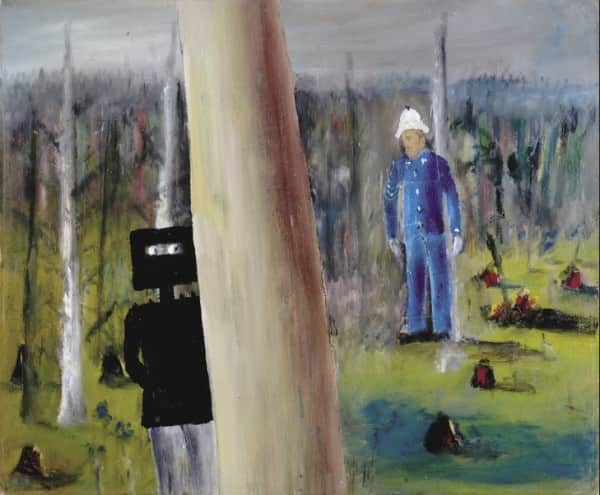

This is perhaps Merthon, 1942, Sidney Nolan

.

On the spur of the moment, it was.9 John was in town at the office and I was telling you about our holidays at Merthon when I was little. You just picked me up and carried me to the car shouting “Off to Merthon, let’s go to Merthon”. And we did – just like that.

“Let’s make love at Merthon” was what I said. And we did – just like that. On the sofa, in the sun, in the living room. Then we raided the pantry and the fridge and took half a cold pie down to the beach for lunch. Bacon and egg pie.

And I found that magic lantern toy Mother brought back from Paris. You couldn’t put it down. “Look how it blinks the images at you – it tricks your mind.” You were going to give that a go you said. It had a funny name …. “praxi” something or other. That’s right … Praxinoscope – I called it the Praxi No Scope.

I showed you the book of Norwegian fairy stories I loved when I was little. About the Ash Lad and his search for the princess at Soria Moria castle – the magic castle east of the sun and west of the moon.10

God. I do remember that day. We talked about everything – about us, about the future, about the war, about art. Lots about poetry, Rimbaud’s poetry. I read to you in French …

.

Je ne parlerai pas, je ne penserai rien :

Mais l’amour infini me montera dans l’âme,

Et j’irai loin, bien loin, comme un bohémien,

Par la nature, heureux comme avec une femme.

.

Then you read my translation. It’s better than the others you said …. none of that linguistic sophistry that hides the real Rimbaud. “You’ve caught the poignancy, his sudden deepening of experience and inner illumination that transforms his verse in such a miraculous way” you said, “we’ll put it in Penguins.”11

I can still hear you reading it. Read it to me No.

.

I will not speak, I will not think,

But love will fill my heart,

And I will go far, far away, bohemian

By nature – happy, as with a woman.

.

(Suddenly shivers)

.

Don’t leave me Nolan. You’ve been at Stonygrad too long. Never leave me and Johnny. You need me No.

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

We got home late that night. John was upset. I could tell. Nolan stopped and showed me his old school at Brighton.

.

“Brighton State School” or “Perspective Love Song”, 1944, Sidney Nolan, AGSA collection.

.

We wandered all around the schoolyard, and he pushed me on the swings. Like he said he used to push all the girls. And then he took me down to St Kilda. We lay on the beach and we loved, and we loved …. God, how we loved. And the biggest fullest moon ever shone all over us. My moonboy lover I called him.

.

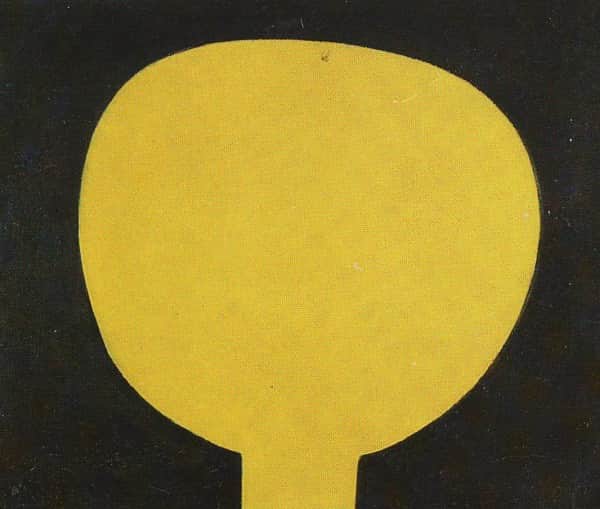

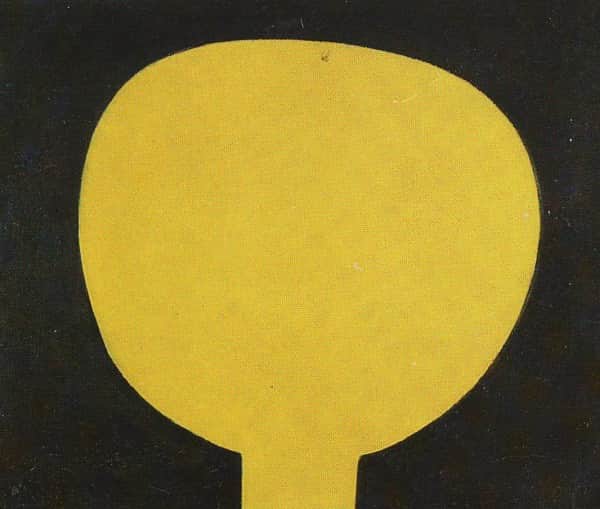

“Moonboy” or “Boy and the Moon”, c 1939-40, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection

.

TO HERSELF

.

And you painted it for me. Our St Kilda secret. “Lovers, Luna Park.” You wrote that on it. Well I’ll tell you something. I’m going to hang it in my dressing room – I’ll get John to put a nail in after tea.12

.

“Lovers, Luna Park”, 1941, Sidney Nolan, Private collection.

.

You and I – we’re ready to paint now Nolan. To paint, and to paint, and to paint. As soon as you get back Nolan, that’s when we’ll start. We will paint Nolan, we will, and there will be nothing like it anywhere – not here, not in Europe, not anywhere.

We found the key No, didn’t we? We found it by accident when you went awol.

Johnny decided you should have another name. I thought of “Robin Murray”. It was my idea. No one will think Robin Murray is you, I said. You’re Nolan, you’re No, you’re Sid – you’re not a Murray, you’re not even a Sidney.

You’re my own Robin Redbreast.13 My little Robin – my Cock Robin.

.

(Sings softly)

.

“Who killed Cock Robin? I said the sparrow, with my bow and arrow, I killed Cock Robin.

All the birds of the air fell a-sighing and a-sobbing

When the heard of the death of poor Cock Robin,

When the heard of the death of poor cock, Robin.”

.

Our little song No.

.

(Singing again)

“… with my bush and marrow, I killed cock, Robin.”

.

Ah Nolan, Nolan, come back today Nolan. Come back today.

I’ll be your sparrow. Ha, there’s special providence in the fall of a sparrow. Hamlet. But I don’t fall quickly do I No? I don’t fall quickly. [SINGS] “Poor cock, Robin.”

Providence in the fall of a sparrow. Ha. I much prefer Rimbaud to Shakespeare. A robin and a sparrow …. [SINGS] “All the birds of the air.”

Johnnie watches birds. And that’s not all he watches. I saw him that night watching us.14 Poor John. He looked so sad. I shouldn’t have told you that Sid. It was your fault in a way. You always knocked on the wall with your rat-a-tat-tat when we were together.

(She demonstrates the knock)

.

Childish perhaps. Boyish. But bloody effective.

Let the bird of loudest lay, on the sole Arabian tree. Shakespeare again. The Phoenix and the Turtle. Ha. We laughed at that line didn’t we No? Ha ha. You’re the phoenix aren’t you my green lad? I’m the turtle.

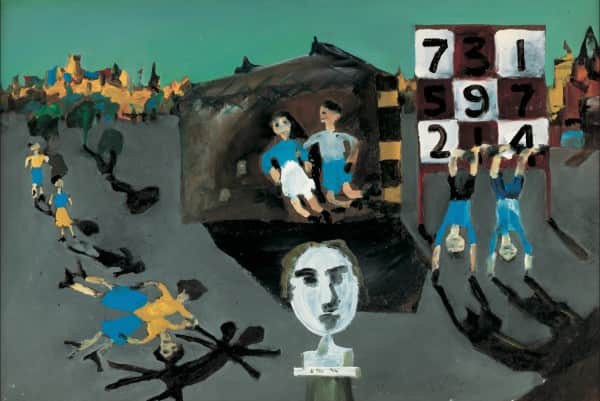

That poem of Ern Malley’s is uncanny. We shall never be that verb perched on the sole Arabian tree.15

.

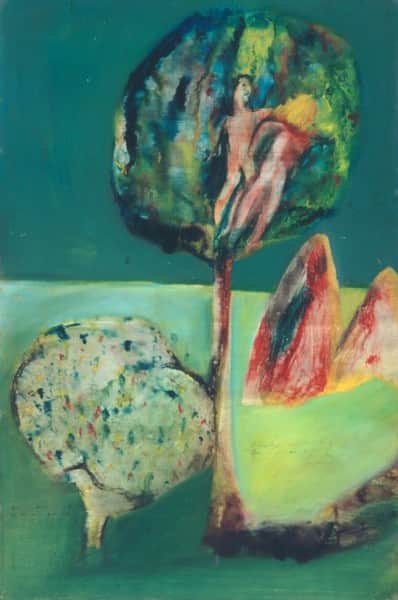

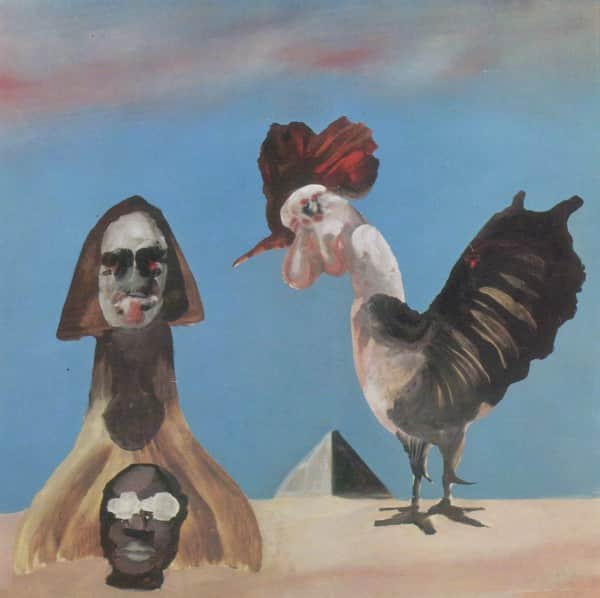

“Arabian Tree”, 1943, Sidney Nolan, Heide collection

(Shudders)

Perhaps we won’t. Will we stay in our Arabian tree No?

.

(Picks up the paintings and looks at them closely)

.

Ah Nolan. Those watching, watching eyes of yours, those beautiful blue watching eyes.

.

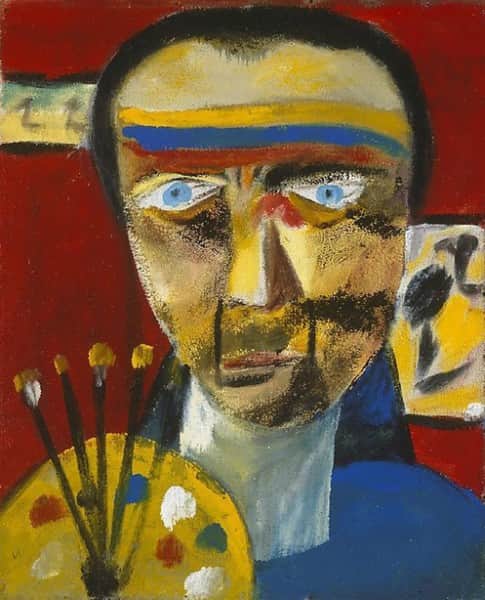

“Self Portrait”, 1943, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW collection.

.

We painted a Ned Kelly helmet over your eyes, didn’t we.

.

Detail, “Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek”, March 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

Poor No, hiding away in your loft in Parkville with the Bechstein.16

.

Sidney Nolan and Joy Hester in his loft studio, Gatehouse Street, Parkville, Melbourne, 1945, photo by Albert Tucker.

.

Ha. Not that you can play it – even before you lost those fingers at Ballarat.17 I’m sorry about that Nolan …. I am. It seemed a good idea.

(Shudders)

Urrgh. New Guinea. You must never leave me Nolan. You wouldn’t have survived. You’d have died up there. I’d have been alone.

.

SPEAKS TO AN IMAGINARY ONSTAGE NOLAN

.

You don’t have to hide anymore Nolan – not anything, not from anyone …. not from anyone, ever again. You don’t have to. Who are you hiding from No? What have you got to hide?

Ah yes …. I must tell you. Barrie Reid. He’s coming down from Brisbane for Christmas.18 You’ll like him. He’s younger than you. A poet – or thinks he is. But you’re a better poet, and you’re not even going to be one. Are you No? You must promise me … LISTEN to me. You must promise me you’re always going to paint.

Don’t go back to thinking you can do both. You know what I think. Poetry and puberty go together, not poetry and painting. WELL? We’ve had this argument before. Don’t go back there!

ANSWER me. Do they or don’t they? Poetry and puberty. Go together? You must always paint what you see Nolan. What you SEE. Not what you THINK. Yes, it is harder. But you must paint it as you SEE it, not as you THINK it.19

That’s just what we did out in the Wimmera.

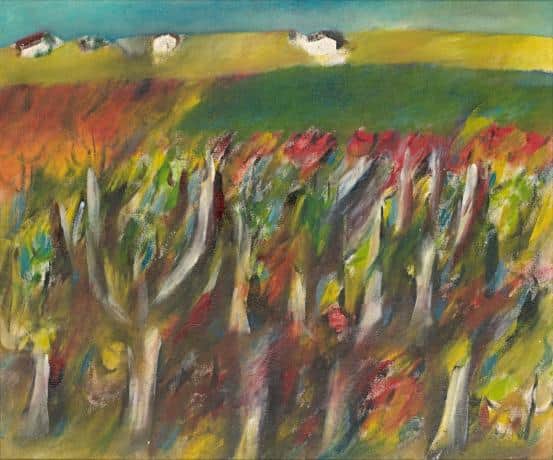

.

“Near Dimboola”, 1944, Sidney Nolan, NGV collection.

.

We saw it differently No – different to the way anyone else has ever seen it and that’s what you painted.

I took out all those canvasses – and you painted. We talked about it in our letters – they’re really a conversation about seeing. I’ve only got these ones you wrote. We should put mine with them …. all together.

.

TO AUDIENCE (Sifting through a bundle of letters ribboned together)

.

There was a letter he wrote about the Little Desert near Wail. Where is it? Here we are: 24 May 1942 – he’d only just got there.

.

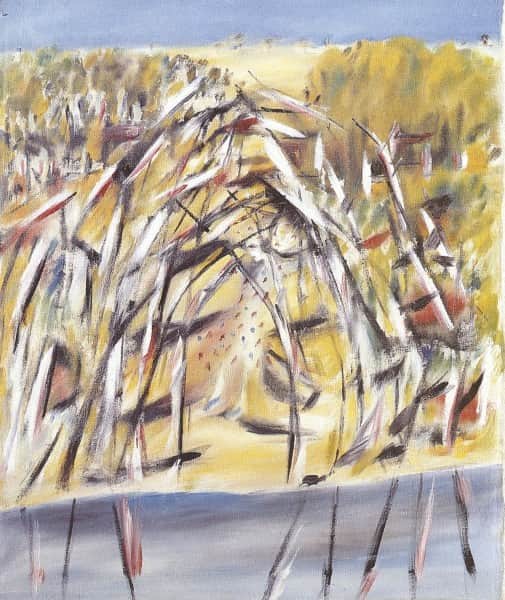

“Little Desert”, 1943, Sidney Nolan, NGV collection.

.

“I wished you could have seen this morning the sun when it first came through. The air was clear and distinct but the sky seemed a soft mist almost as if there was an ordinary morning mist, but one that stopped a few feet away and the air between belonging altogether to another day. The line of the desert was a dark blue, the colour the sea often promises during the thunder storm but never quite reaches. ….. On top of this blue line and more like a million ropes heaped together than anything else was a semi-circle of this compact pink light, isolated in its own feeling and part of the sky only because of nostalgic mischance. A strange thing to float over the burnt honeysuckle trees.”20

He does write well. And he’s right … I know Little Desert well …. we camped there years ago with Sammy.21

.

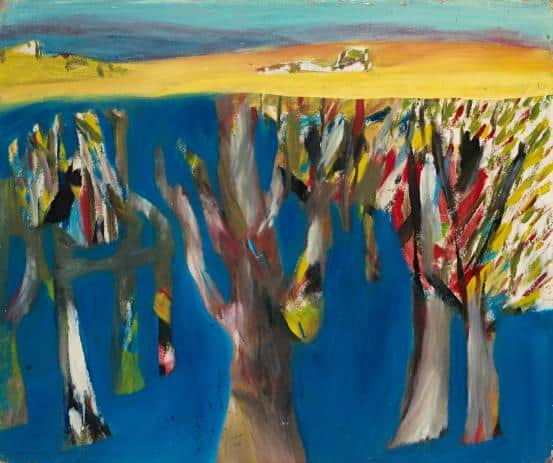

“Lagoon Wimmera”, 1943, Sidney Nolan, NGV collection.

.

We’d write to each other as if we we were both there talking about what we saw, how we saw it, and how we’d paint it. We wanted to shift things about.

There’s another one here somewhere about just that. Here it is:

.

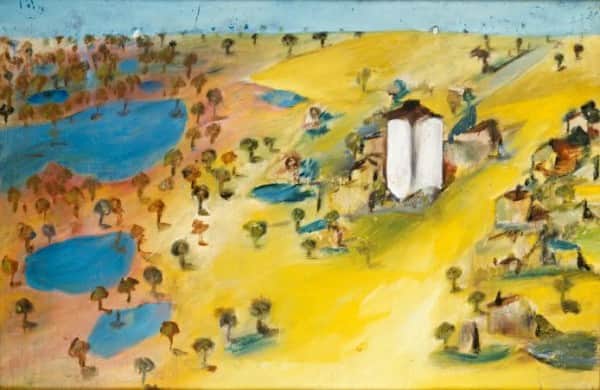

“Wimmera (from Mt Arapiles)”, 1943, Sidney Nolan, NGV collection.

.

“Juxtaposition of things as they really are, not a selected array of images posed up to make a picture that will fit in with whatever symbols you have decided they mean. No symbols.

“Perhaps that is where things go astray with painting. We’re not asked to say what figures, or apples, mean. We’re asked to say what they look like …

.

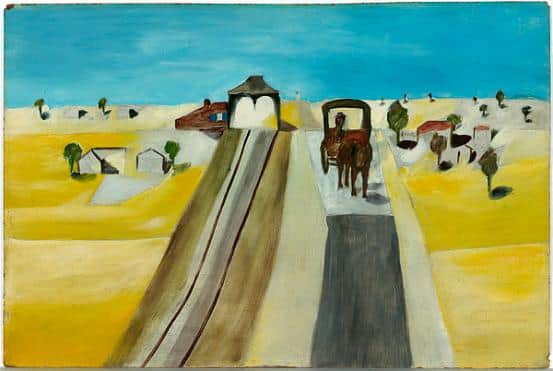

“Kiata”, 1943, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

“Railway lines are never far away from the story & up here the silos are not far either, & that is the way they have got to be painted.”22

Where was I? Oh yes. Poetry and painting.

Nolan’s quite brilliant you know. I can pick a painter – even if I can’t be one myself. Those Wimmera paintings of Sid’s are much much better as paintings than his poems are as poetry He SEES so well. I prompt him. John swears he’s got such a subtle, meditative mind that it embraces his eyes … his unfailing eye, and elucidates it. He has ultimate …… simplicity, sensitivity, extreme sophistication.23

God, I wish I had your eyes Nolan. Then I could create – how I would create ….

So ….. no more serious poetry thank you very much young Sidney Nolan.

But he can write poems for me. Listen to this one I keep on the mantle here. Johnny’s seen it. He likes it. He’s happy for me.

.

(Tenderly, lovingly reads Nolan’s poem from the sheet)

.

“We walked here

remember.

Somewhere near

the creek began to run,

its scent like your caress, warm in the sun.

Somewhere here the bush began.

.

“Girl in a spotted dress”, c 1943, Sidney Nolan, Private collection.

.

The leaves close to us,

only the birds

saw us looking,

only the creek

ran with us,

only the scent, warm,

caressing, saw our caress.

The sunlight

on the creek shines on me,

your scent touches me

and years of parting

part the bush for me.”24

.

TO HERSELF

.

Only the birds saw us looking. Michael Keon. I’d forgotten him.

Nolan told Michael that Heide was Soria Moria – somewhere east of the sun, west of the moon.25

.

(Smiling, musing)

.

The old book of Mother’s I showed you at Merthon that day … with Norwegian folk stories and the wonderful painting.

.

“Soria Moria Castle”, 1881, Theodor Kittelsen, Nationalgalleriet Oslo collection.

.

It reminded us of Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea.

.

“The Monk by the Sea”, 1808-1810, Caspar David Friedrich, Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin collection.

.

And Ned Kelly.26

.

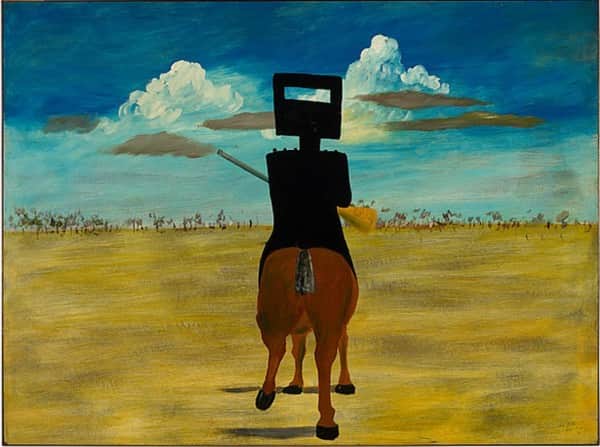

“Ned Kelly”, August 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

Only the birds saw us looking. Ah yes. Michael Keon. Michael liked Hopkins. Used to quote him. He thought he owned Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Nolan was jealous of Michael. He needn’t have been …. even though I’d take Michael for a walk now and then … and we’d come home hot and sweaty.27

Michael loved my mind. I loved watching his little bare bottom. He was such a boy Michael.

He quoted Hopkins about me. My heart in hiding stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing! Ha, I can quote Hopkins too.28 He told John perhaps I hid my heart away from being stirred.

John’s said that. John knows though. He knows my heart stirs for Robin Redbreast. Poor Johnny.

.

your scent touches me

and years of parting

part the bush for me.

.

That’s right. Part the bush .… That’s when we thought of it. Let’s put Kelly in our landscape.

.

(She sets out one by one the other paintings with Kelly from the dozen standing against the wall. As she does the sequence begins of images of these early Kellys)

.

Art and life ….

.

“Death of Constable Scanlon”, April 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

and myth and love ….

.

“Bush picnic”, September 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

and separation and leaving ….

.

“The chase”, September-October 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

and …. all of it,

.

“The encounter”, September 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

all of everything in this landscape – in our landscapes No. The landscapes of our minds. The landscapes of our lives together. Yours and mine. All fired in the crucible of our Australian landscape.

The suns are hammered nightwards as they sleep … The suns are being hammered by the terror. We’re painting those lines by Kershaw, you and I Nolan, we’re painting them.29

And it’s working. It really is.

Have you painted anything out at Stonygrad? I wonder. I hope not. You said you’d wait till I got back from Brisbane.

Whose idea was the helmet No? Was it Max’s up at Glenrowan with you last year?30 No. It couldn’t have been Max. You’d already painted Kelly on those smaller boards.

.

(She flicks through a stack of smaller paintings)

.

Yes, here’s one, March 14. That was last year. This is the first.

.

“Kelly and Sergeant Kennedy”, March 1945, Sidney Nolan, CMAG collection.

.

I’m not sure who it was – we were excited – was it you or was it me? I don’t know. No. It must have been us together. We are one, you and I – and John too. But we are the painters Nolan, you and I are the painters.

It really is a pity about Stringy Bark Creek not being here any more.

.

“Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek”, March 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

You shouldn’t have sold that to Clive Turnbull No. Even if it was in the South Melbourne exhibition last year.31 The first Kelly to be shown, and all by itself.

.

City of South Melbourne Arts Festival, May-June 1946. The first exhibition of a Kelly painting. The woman is Esther Paterson, the aunt of Nolan’s first wife Elizabeth.

.

Yes, I know he’s going to have a photo of it in his new book. And yes, I know he set you going with his little Kellyana book. But you really didn’t have to sell it. We’d have given you money. We’ve been doing that for years.

What a circus that catalogue – alphabetical listing and you’re there mixed in with all your Paterson in-laws.32 Well, former in-laws.

.

TO OFFSTAGE

.

Almost ready Johnny. Scones are just going in.

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

I’m over forty! Surely not you say – well, I am. I’m forty one. And fortunate I suppose. We are fortunate, John and I. Not exactly heaps of money, but certainly enough to do what we want.

No that’s not right. Not to do what we want – that sounds selfish. But we do have something to offer – and after the last six years of war, the world surely needs things that uplift. We have something important. More than important. It’s …. so vital after these dreadful dreadful years. And the peace looks like it mightn’t be all that different. We are slow learners .. slow learners.

That’s why it’s all the more important of course. What is? Well, Art – of course. No, not your ordinary village scene, or still life, or your nice gum tree or a lovely wheat field. No. What is essential for life is Art that challenges and inspires. Art that makes a difference.

And we can afford to do this. Here in Melbourne. For the whole country. In our own way.

Kenneth Clark’s just written something about this. Here it is in Cornhill. Listen to this:

Art and Democracy.

Where’s the bit I want? Here.

“We know that certain minds can create an order in the chaos of appearances which other minds can contemplate with delight.

“We know that certain eyes can see in nature shapes and colours to which our eyes were blind; and can persuade us gradually to see them for ourselves.

“And we know that these revelations of the order and mystery of the universe cannot be made immediately understandable to the average man.”33

Is that pompous? I don’t think so. That’s what I want to do. Bring worthwhile Art to those who have the … the good fortune to be able to appreciate it.

And not just to bring it. To create it. Yes, create it. With people we love, who we share our lives with, our thoughts with. These people are our life. And of course, we do help them a little bit here and there with money. We can afford to do that. And we want to.

I’ve always wanted to create. But I can’t really. Not me myself. Not directly.

I’ll tell you.

When I was little I was … well I always thought I was just like everyone else. We lived in a nice house. In Toorak. I had a lovely nanny. I didn’t go to school until I was 13 or 14. I had my own teacher at home. And we had lovely long summer holidays at Merthon down on the bay at Sorrento. I suppose I thought everyone was more or less like that. Well not quite.

I didn’t like school. I wasn’t really very good at some things. Well, I wasn’t best. And some of the other girls would tease me. They teased me a lot … and I don’t like that. I didn’t stay – only a few years.

I suppose I don’t really like not getting my own way. Not that so much. But I do like to do things well, and I know how to do things well …. and properly. I …..

And I’m shy really. Although you probably don’t think so. I’m still shy. Even now, but I don’t let on. I’ve learned to get by … get my way. Most of the time. Not always.

I get upset then.

Did I say I was a Baillieu? Yes, well. That wasn’t as good as it may sound. Especially if you weren’t a Baillieu boy. Baillieu girls were just meant to be seen – not heard. But I like to be heard. If you have something to say …. say it. And I do have things to say.

I suppose I should tell you about Lenny. Leonard Quinn. My husband. Well, my first husband. From Boston. They all told me not to marry him. I was silly. Young and silly. In love and silly. Engaged the moment I turned 21. Married in 3 months. Finito in three years.

He left me in Paris … in a hospital in Paris. Left me with his bloody gonorrhea, no womb and deaf in one ear. Daddy came and brought me home.

It was the talk of Toorak

.

(Suddenly sobbing uncontrolably)

.

I … just … so … much … wanted …. a child … of … my … own. And I never will. I never will.

.

(Recovering)

.

That’s enough of that. I don’t tell people about that. I shouldn’t have mentioned it. It upsets me … upsets me too much … so much..

Nolan knows. John told him. He thought he had to – to explain about me getting upset sometimes. Highly strung is what people say. I’m highly strung …. ha.

And then I met John. At a tennis afternoon. Dear Johnnie. So understanding my John.

He understood about me and Sammy. Sam Atyeo. Well, fair enough too. He and Moya amused themselves together. Well I told John he should. And she still loved Sam. She still loves him. Even now.

She went out to him in the West Indies after Bob stayed there on her way back. Bob – that’s John’s sister Cynthia. We call her Bob. Why? No idea.

We used to see a lot of Bob and her crowd in those days. She and Sam were good friends – indeed, more than just good friends. That’s the expression I think. Moya, Moya Dyring, was Sammy’s girlfriend. She was always around him. And there was Fred Ward who had the shop with Bob. And Doc Evatt and Mary Alice.

Sammy had eyes. He could see. Not like Nolan, not like me. But he could see. Sam and I were a team too. And John. Not Moya – although she painted in her way. Better with watercolour. She painted me for Sammy. Funny thing to do.

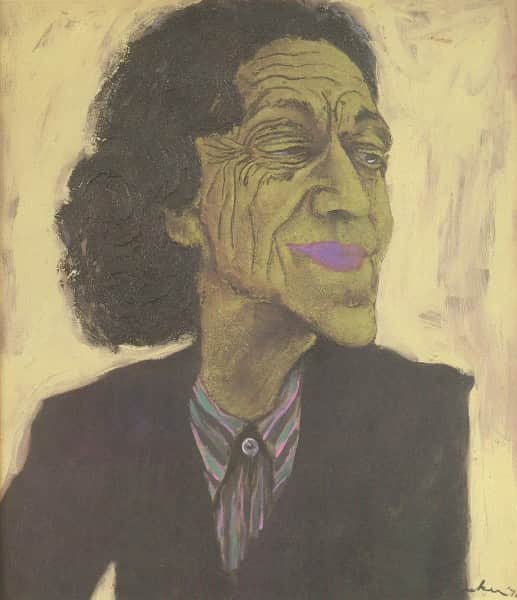

.

“Sunday”, c 1934, Moya Dyring, Private collection.

.

I tried to paint … to be a creator. Do you understand? I know I was meant to create. Create “great Art” I thought. I wanted to paint. So I went to George Bell’s classes. Sammy knew him …. and Arnold Shore. But they criticised me and it was all quite awful.

I know I had the right ideas – I tried to paint what I saw. As I SAW it. With these eyes. But I couldn’t. My eye wasn’t true enough, and my brush couldn’t, wouldn’t, do what I wanted. It was a false brush.

They always looked like everyone else’s. All I did was paint what other people saw – not what I saw.

I was very competent he said. Tsch … competent. What a ridiculous word. Who wants to be competent. Painters who are competent shouldn’t paint.

I told him that. “Painters who are competent should not paint” I said. I suppose I shouldn’t have raised my voice so much.

So I stopped it all. Burned everything except just the one. I’ll show you.

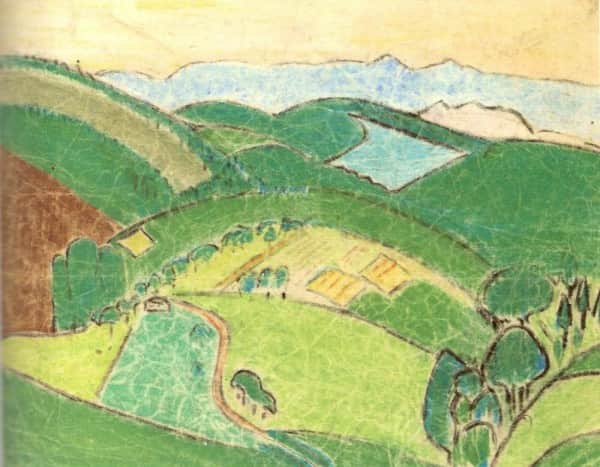

.

“Landscape”, c 1933, Sunday Reed, Private collection.

.

There. See …. Ah well. If you have an eye, you’ll understand.

But look at this one. This is Sammy’s.

.

“Organised line to yellow”, c 1933, Sam Atyeo, NGA collection.

.

It’s his best. By far. Organised Line to Yellow. See the difference!

And then Sam left me. We’d only been out here at Heide a year. And he just announced he was going … off …. leaving me. Off to Vence. Vence! He wouldn’t have known of Vence if I hadn’t told him. I stayed there with Lenny.

I went all to pieces when Sammy left. I wouldn’t have survived without Johnnie. Darling John.

You are so good to me Johnnie.

God. I’ve been talking too much. The scones are burning.

.

(Takes scones from oven)

.

TO OFFSTAGE (calling out window to John)

Ready John. Ready. Just boiling the water.

.

TO HERSELF

.

Why did I say all that?

I should have told them about Nolan. Not about Sammy.

Ah Nolan. It’s 8 years since you came into my life. I’ll never forget that night.

“Sun” John said. He telephoned from the office. “Sun. I’m bringing someone home for dinner. A young man who says he is a painter. His name’s Nolan. Sidney Nolan. You’ll like him.”

That’s what he said – “You’ll like him – and you’ll like his painting even more”.

You were right John. Right on both counts.

That very first night I asked Nolan was he a painter or an artist. He just looked at me and said nothing. Absolutely nothing. Just raised an eyebrow a bit and tilted his head back. And said nothing.

.

RECREATING

.

“Don’t just sit there. Answer me. What are you? An artist or a painter”

“Smiling is not an answer. Well? I’ve seen your work? I know I’ve seen the work you brought out with John. Telling me what I know is not an answer”

“Me tell you? That’s not an answer either. I know what I think you are. I want to know what you think you are.”

“Why? I’ll tell you why Sidney Nolan. You need to decide whether you want to be an artist or a painter for this very good reason.”

“Painters should not have wives. And it seems you soon will.”34

.

TO HERSELF

.

Well you don’t now No. Do you?

And that’s for the best. Elizabeth was not good for you No – you would never be what you are now if we hadn’t told her. Well it was John told her.35

But I did want to help you both. I did. Johnnie told her everything that day in his office. You could have both lived at Heide. I would have helped her raise the baby when it arrived. I wanted to do that.

John only told her about you and me, so she’d understand how important it was that we worked together. John knows that. She’s an artist – even an artist should have understood that.

But no. And so much the better.

Because you are a painter Nolan. No mere artist you. Even if you’re not so sure yourself.

I knew it from the moment I met you. Not from those scraps you brought with you that first night. I guessed you’d slapped them together the day before – and I was right wasn’t I? Not that they weren’t good.

No. I knew you were a painter when I saw your eyes. And what they did. WHAT they saw, and HOW they saw. You have a painter’s eyes Nolan. And together we will show the world something they’ve never seen before.

This landscape of ours, with its light, and its shade, and its wheat fields, and its brown ploughed fields, and its bush fired black, and its pock marking trees, and its flatness and its ranges. This landscape we will paint as it’s never been seen before.

.

TO IMAGINARY NOLAN

.

Here Nolan. I have this idea. Remember Bert’s myth essay in Penguins a few years back. I’ve looked it up to show you.

Here it is.

.

(Reads from Penguins 4)

“Art can assimilate and condense experience into the form of a valid myth ….. and transmit it back into society, thus raising human consciousness to a higher magnitude of fullness and complexity.”36

Bert’s quite right. He’s clever Bert. And that’s exactly what we’re doing with the Kellys. But we can do more. Still more. I want to try something. Something that will be very special.

And here’s my idea No.

When are we most creative of all? When we make love – that’s when you and I are most creative. Well, it should be, except …. you know. But it still can be. I can still create …. with you.

I want to tell you just what I see, what I really SEE, when you part the bush for me … when

.

(singing)

.

“I kill cock, Robin” …. And then I want you to paint it. Paint it just as I tell you it is.

It will be my own creation. My very own, my own special creation. And yours too, of course. Yours too.

.

TO HERSELF (as she picks up a largish doll sitting on a chair)

.

Gethe. What are you doing here? Who told you I cut fresh lavender for your stuffing? Clever Gethe. But you’re not having arvo tea with us. You should be resting.

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

This is Gethe. Gethsemane. She’s my doll without a face. My substitute child if I’m honest… substitution therapy.37

Gethe’s not been well. In fact, Joy’s been painting her.

.

“Gethsamene”, c 1946, Joy Hester, Heide collection.

.

That’s Joy Hester … Bert Tucker’s wife, Sweeney’s mother. Joy hasn’t been well either.

I look after Joy. Well, John and I look after them both. We help with money … and with love, and books, and talk. But she’s had this dreadful cough for ages, and that big lump on her neck.

I said to her we could look after Sweeney. He’s almost two, darling Weeno. And Joy said a strange thing. Promise me she said – and she was very serious – promise me that if anything ever happens to me, you and John will look after Weeno.

It struck a chord because Nolan said something similar once. Interesting. Joy confides in me. I know she had a bit of a fling with Sid soon after he got back from the Wimmera.38

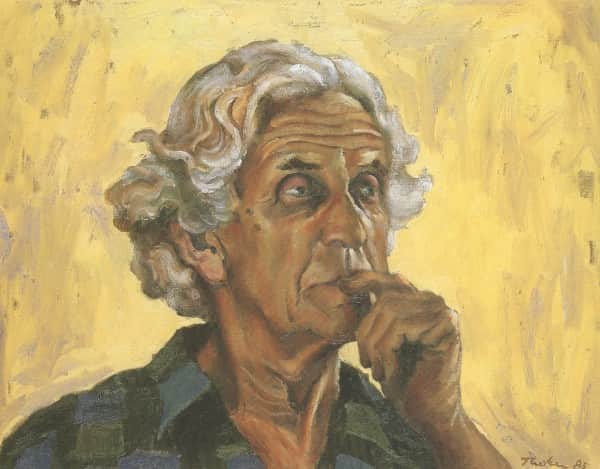

And Nolan’s so fond of Sweeney. One day down at Point Lonsdale about a year ago, the five of us went for the day. No carried the little fella for ages and Bert took some wonderful photos of us all.

Anyway, enough of that. And it’s soon off to bed with you young Gethe.

Reg Ellery says Gethe’s good for me. Reg Ellery’s one of us …. a psychiatrist. You might know his book Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare. We published it. Reed & Harris that is.39 … Sid did the cover … perhaps you know the painting?

.

“Head of Soldier”, December 1942, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

It’s supposed to be his commanding officer … Captain Bilby I think. I met him.

Well the book certainly didn’t please the warmongers, and we used the Goya paintings for illustrations. “Disasters of War”.40

.

“Wonderful Heroism” from “The Disasters of War”, 1810-1820, Francisco Goya.

.

Timeless. Hopeless. Senseless. Haunting. See them once and you’ll never forget them. Which is just the point of course. No one ever forgets the dismembered bits of that corpse stuck up on the tree. But how much difference does it make really I wonder?

.

TO OFFSTAGE (calling out window to John)

Kettle’s boiled John. Tea’s made. Scones are ready. Leave it now. Come on in.

(She commences stacking a tray with teapot, cups, scones etc. Stops and listens to sounds of a car on a gravel drive, male voices, car leaving. As she walks off R with tray, there comes the distinctive rat-a-tat-tat sound of Nolan’s door knock. She almost drops the tray putting it down hurriedly, and runs off R shrilling, almost wailing in happiness)

.

Eeeaaah. He’s here. No’s here. Eeeaaah. Nolan, Nolan!

.

CURTAIN

.

————————————–

.

ACT 2

.

AGAIN THE KITCHEN AT HEIDE. THE PROPS HAVE CHANGED TO REFLECT THE PASSAGE OF TIME FROM AN AFTERNOON IN DECEMBER 1946 TO ANOTHER AFTERNOON 35 YEARS LATER – PERHAPS TO THE DAY. SUNDAY IS 76. IT IS MID DECEMBER 1981. CURTAIN RISES ON SUNDAY SITTING AT KITCHEN TABLE. THERE ARE NO PAINTINGS. SHE GAZES AT WALL R WHERE THE PAINTINGS WERE STACKED IN ACT 1.

.

TO HERSELF

.

And so it goes. So it all goes. All goes. Goes. Ha. Gone, more like. Everything, everyone is gone. You went 35 years ago Nolan and everything else has followed. It’s been a long procession. I’m emptied …. and I’ve written you Nolan, written a last letter to tell you how I feel.

Tell you that I understand. At least I think I understand.

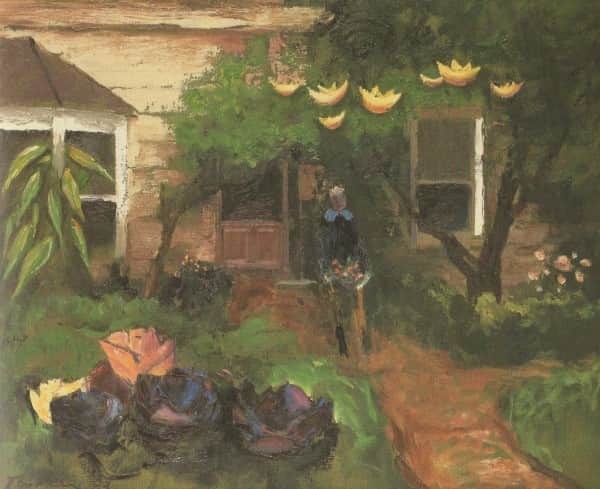

Everyone has left me Nolan. And everything. No, that’s not quite right. Not everything. Our Kellys are still here. Actually they’re back here. Back from the National Gallery. I gave them to Mollison. With love.

But you know that don’t you. You tried to remove my “with love” message when no one was looking.41Mary tried to stop you. Naughty No. Still the Irish scallywag – that’s what Jean thought you were. “Your great Nolan,” she said, “the great No is nothing but an Irish scallywag.”42Ha. Perhaps she’s right.

Is that all you are Nolan? An Irish scallywag?

Ah, yes. The Kellys. They’re in the new house down the hill towards the river. Heide II. It’s a gallery now. Johnny and I gave it to the people. Well sort of gave it.

Old Heide’s still here and I’m still here, sitting in the kitchen at the table where we painted them. Well – we painted them in the dining room mainly.

Yes, I’m still here …. just. Most likely I’m only just still here. Barrie will look after Heide when I’m gone.

.

TO IMAGINARY NOLAN

.

Ah Nolan – of course you know John died last Saturday, don’t you? We’d always intended to go in our own way, on our own terms. John’s been so brave, but he’d had enough. Me – I’m just so tired …. and empty …. I’m emptied.

I don’t want another week like this last one. I always told John I’d follow swiftly if he went first. And I think I will. Love will follow swiftly. Barrie thinks I should. He’ll help me.

We spoke about you last night Nolan. He told me you’re in Australia again. But I already knew that. Nadine Amadio said she’d seen you and told you John was dying and you should visit him.43

John was furious. Not that he didn’t want to see you Nolan. He just didn’t want to see you if you’d only come because he was dying. There’s nothing he’d have wanted more than to know you wanted to see us again.

Nadine shouldn’t have done that. She presumes a little too much. And I wonder too how still her tongue is. I told her once Nolan, how I felt most creative with you inside me.44 I shouldn’t have told her that.

You know, sometimes I still think you’ll come back Nolan. You’ve never seen the new house – or have you? Have you been back to Heide since that time with Bob?

“We’re married” you said. Just that. The two of you breezed in unannounced and you looked at me and said “we’re married”.45

And I just said “no”

.

RECREATING (In a cadenza of ‘no’ at least 35 times)

.

“No Nolan” I said. “No no no no no No. No no. No No. Nolan, no…… etc”

.

TO HERSELF

.

What time is it. Yes, 3.30. I should prepare arvo tea. I can’t be bothered doing fresh scones. I’ll reheat yesterdays.

God. I almost forgot. That clever girl who’s just done the exhibition on Joy – what’s her name? My memory’s getting atrocious! She’s coming at 4, bringing back the stuff I loaned her.46

Johnny and I went in to the opening. The last time we went out together. We both wore white …. it was John’s elegant farewell …. but people didn’t know. I felt a faint shadow at his side. Barrie’s friend Shelton was here as we left …. “Keep writing poems Shelley my boy” John said as we got into the car, “stay alive and I bid you a fond farewell.”47

.

(She commences preparation of afternoon tea. Her movements doing this reflect her 76 years – on one occasion when standing up from a kneeling position she will hold her thighs on straightening and exclaim “Oh, my sainted hams!” She gradually becomes less focussed on preparing afternoon tea, and eventually, once the jug boils, pays no further attention to it.)

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

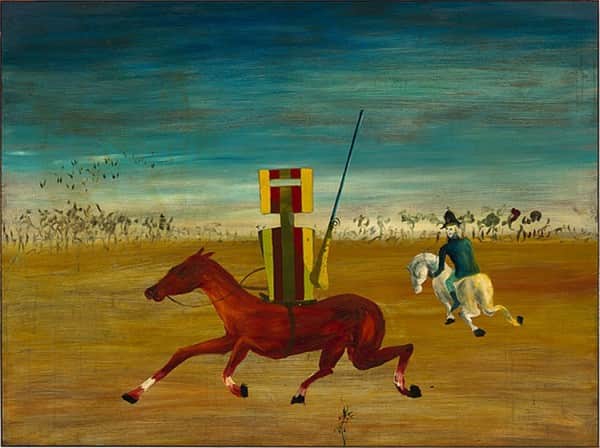

It’s a strange feeling knowing our Kellys are so close again. Well not all of them. Just the twenty five I gave the nation. With love. Not that first one Turnbull bought. And not the one Nolan brought back from Stonygrad.

He waltzed in that day with half a dozen four-by-threes under his arm, John in his wake, slapped them over there against that wall, picked me up and whirled me around yelling “I’m back Sun, I’m back. And have I got some things to show you!”

And he surely did.

.

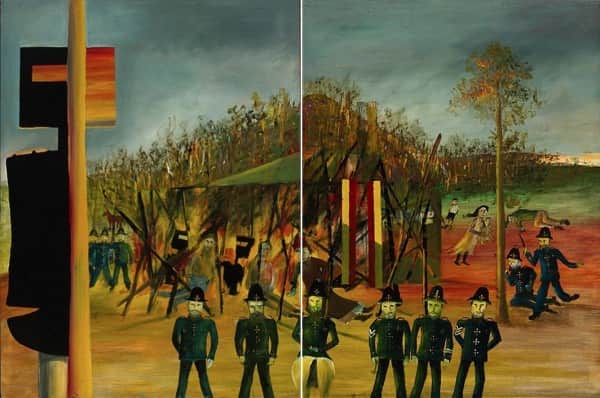

“Burning at Glenrowan”and “Siege at Glenrowan”, October-November 1946, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

He’d chopped the big six-by-four Glenrowan in half, right down the middle, right through the horse’s bum. “Bloody hell Sid” we both said, “what possessed you?”

“Too big, it was too bloody big. Jack Bellew said so.” They’d had a bit too much of the Vassilieff home brew, so he just grabbed a saw and cut it clean in half. “Now there’s two masterpieces Sun, not just the one.”48

Crazy. He could be plain crazy. But it was so good he was back.

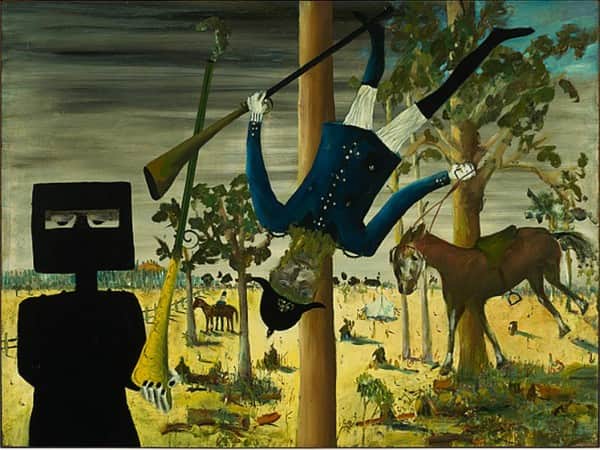

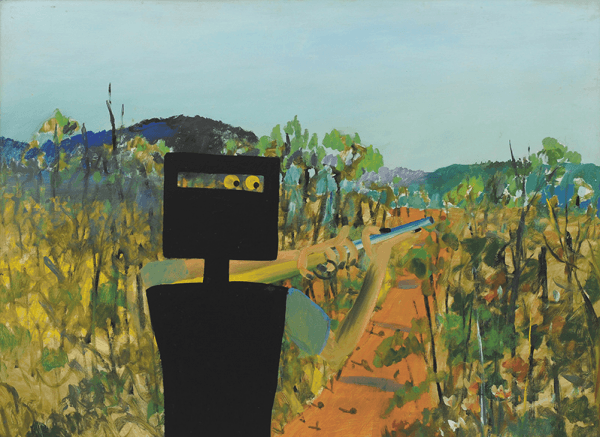

And then he showed me the new one – First Class Marksman.49

.

“First Class Marksman”, December 1946, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW collection.

.

“All my own Sun, all my very own. How brilliant is that!”

And I just stared at it. “No, it’s not brilliant” I said. “I’m not sure I approve of it at all. It’s … it’s …” I couldn’t quite find the words.

No, that’s not right. I know exactly why I didn’t approve. He’d done it without me. Instead, I told him I didn’t like the look of this Ned.

.

RECREATING

.

I don’t like his eyes Nolan. Look at his eyes. I’ve just noticed them. He’s looking both ways …. front and back. You’ve painted Janus.

Why is Kelly two faced Nolan? Don’t just stand there smiling. Tell me No – why is he Janus-faced? Who is he shooting at?

It’s target practice? Maybe … maybe it is … but target practice for what?

Why is he looking back at me if he’s aiming ahead? He’s not looking back you say? You stand here …. right HERE. See if he’s not looking back at you! You should know, you painted the thing.

Why Nolan? Tell me why.

All right. You can’t … or you won’t. Either way. Put it away, hide it … I don’t want him looking at me like that. I don’t want to see it. Put it away I said.

Thank you.

We’ll move on shall we? I’ve something important to tell you No … but it must wait till tomorrow …. after tonight.

.

TO HERSELF

.

Ah yes … tonight … that night. We went to bed early.

I told you again …. didn’t I Nolan? …. I told you I wanted to describe exactly what I saw, what I really SAW, when we made love. And then you’d paint it. Paint it just as I told you it was.

It would be my very own, my own special creation.

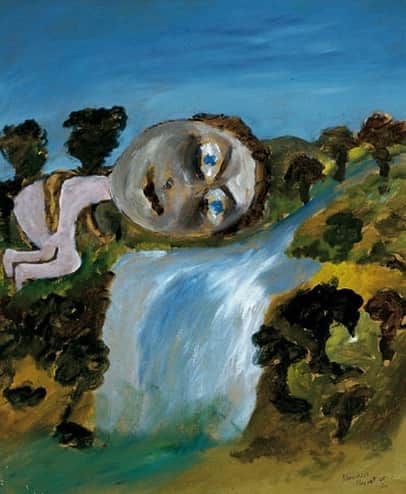

And that night, as we made love, what I saw … I can see it now … still.

.

“Soria Moria Castle”, 1881, Theodor Kittelsen, Nationalgalleriet Oslo collection.

.

What I saw was Soria Moria castle – that painting. I felt one with everything, with the golden spires of the castle, with the landscape, with the Ash Lad, with you … inside me.

And I told you what I saw. Not just the landscape. I saw what the landscape would see if it had eyes.

That Kelly landscape’s not finished after all, I said. It must show what the landscape sees. Paint the magic castle into the landscape – paint it as the waterhole sees it.

.

Detail from”Soria Moria Castle”, 1881, Theodor Kittelsen, Nationalgalleriet Oslo collection.

.

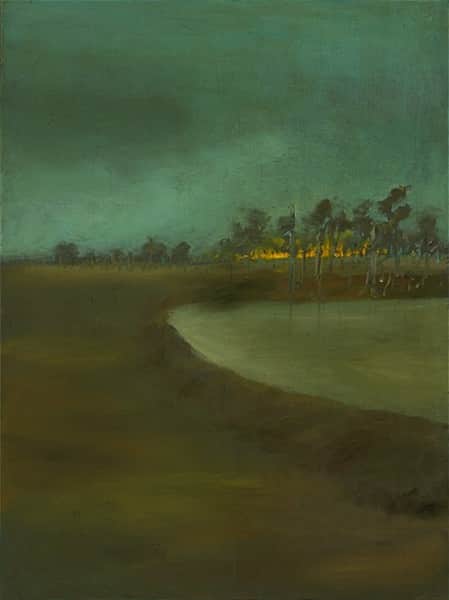

And that’s just what we did. The landscape became the bush eternal with sun, and fire, and castle – all of them, there on the horizon.

.

Detail from “Landscape”, January 1947, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

And that’s how it finished up.

It was a busy January. Ha. I’d not thought of that before …. it was January …. the two faces of January.

About half a dozen Kellys were finished that January. The first was Landscape.

.

“Landscape”, January 1947, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

I wont go through them all. But things had changed. I see it now looking back. He always painted more than me of course, but now he was doing much more. I was doing much less.

You can notice too, after Marksman the tonings are darker and more sombre. Before Marksman there was brightness and light …. an exuberance. Not a lot of Rousseau and sunlight after Marksman.50

Looking back, I wonder perhaps if we’d sensed something because we each signed off on a painting. Visual signatures. I painted the red floor tiles in Trial51 and you might have noticed …. Nolan painted in a Robin Redbreast sitting on the fence in Quilting.

.

“Quilting the armour”, January 1947, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

There. Can you see the Robin?

.

Detail from “Quilting the armour”, January 1947, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

It never occurred to me at the time – but perhaps it was more than a signature. Perhaps even then my Robin was about to fly off.

But whichever way you look at it, there’s no doubting Marksman was a watershed. I never liked it. I ended up giving it to Sweeney and he sold it to McAlpine.52 Ha. It’s probably back with Nolan – he always wanted it back, that one in particular …. and Ned Kelly.

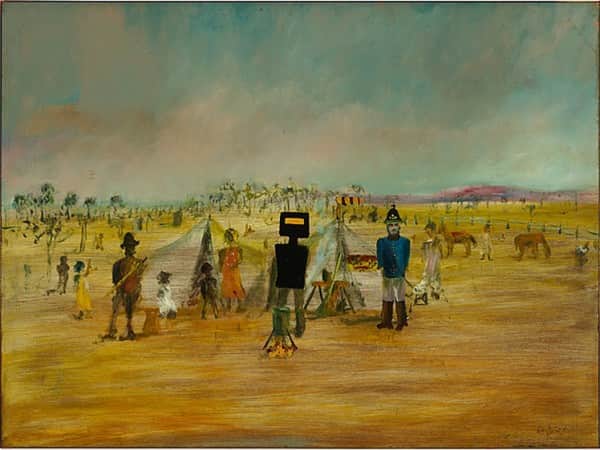

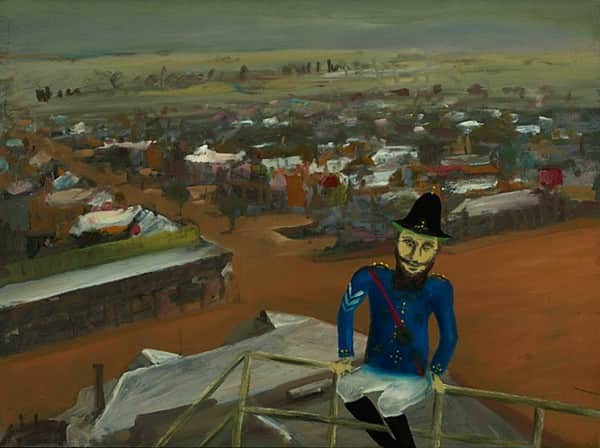

He only did a few more Kellys at Heide. Watchtower was the very last.

.

“The watch tower”, July 1947, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

.

I had nothing to do with any of them. All dark … all gloomy.

That change in tone and mood doesn’t come out when you see them in an exhibition. Right from the beginning, at Velasquez gallery, we hung them in the narrative sequence. But they weren’t painted in that order.

I recognised Watchtower as soon as I saw it. It’s a photo of Longreach from Walkabout Magazine a few months earlier. We had it.

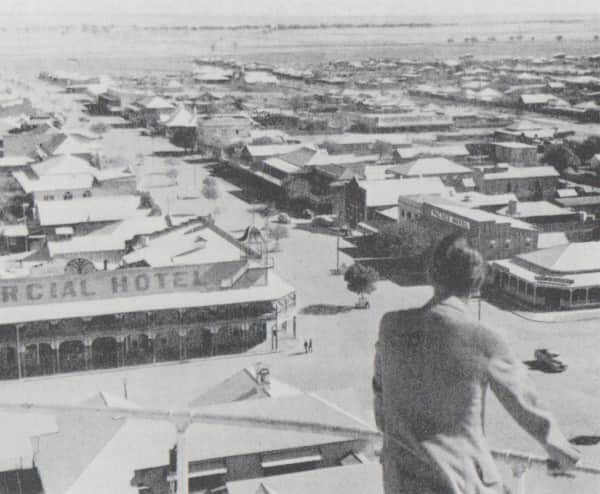

.

Longreach, Queensland, in “Walkabout Magazine”, March 1947

.

Funny thing is …. that man standing on the lookout in the photo is the dead spit of Nolan.53 Ha …. looking for the way out of town were you Nolan?

Well they’re all back here now, all down the hill in Heide II. And with more security than Ned ever had himself. Such is life. Ha. Such is fame.

.

TO IMAGINARY NOLAN

.

I haven’t seen them Nolan. I can’t bring myself to look at them. I could though if you came with me. When they went to Canberra I promised myself – “that’s that” I said. They’d gone too. Just like everything else. Everyone else.

John went down to look at them before the opening …. by himself. It was hard for him He was so ill. But I couldn’t go …. not without you.

.

RECREATING

.

(She takes a telephone and speaks)

.

Why did you leave me Nolan?

.

(Becoming very animated)

.

Why? Why did you leave me. Answer me! [LISTENS] “You’ll turn up one day, just like normal?” No. That is not an answer. What? “I’ll see you coming through the lavender bushes and the sun will be shining?”54That is not a reason. No. No. It isn’t.

I did not say that I would go to Paris with you. [LISTENS] The two of us would go with Sweeney? No, I never said that.

I don’t understand Nolan, I just don’t understand. What? “When you come back you’ll explain to me why I don’t understand?”

It’s you who don’t understand. You don’t understand, do you? I’m not talking about why you left Heide and went to Brisbane, I’m talking about you not coming back. I’m talking about you not contacting me in all these years, [SOBBING] in all these long, miserable, bloody, lonely 34 years. And five months. And two days. [LISTENS] What? Keeping count? Yes, I have kept count.

.

(She crumples, completely distraught. The phone dangles at the end of the cord)

.

TO HERSELF

.

No contact ever – except three years ago when Mary insisted you call. And that was how our conversation went. You were humiliating …. I felt so empty …. so emptied …. you trivialised everything ….

For the first time … the first time ever, I wondered if you had ever loved me .… really loved me .… ever.

And that stark, barren contemplation absorbed me for days and days. I convinced myself you hadn’t …. it was a dark place Nolan … even burning my letters to you brought no light. I burned them all …. I should have known better.55

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

It wasn’t that I didn’t want him to go up to Brisbane to Barrie Reid.56 I encouraged that. He knows I did. But somehow I think its one of the things he’s held against me.

You see Barrie arrived down from Brisbane just before that Christmas. Nolan was back from Stonygrad barely a week – he was so busy painting Kellys he hardly noticed him.

But gradually the four of us fell into a pattern of walking and talking. He and Nolan talked of poetry, and for a long time it seemed they never stopped talking.57 They stayed here at Heide and then at Nolan’s studio in Parkhurst.

Barrie still says Nolan is the most extraordinary man he’s ever known. He puts it quite simply – “I met Nolan and I fell in love with him.”58

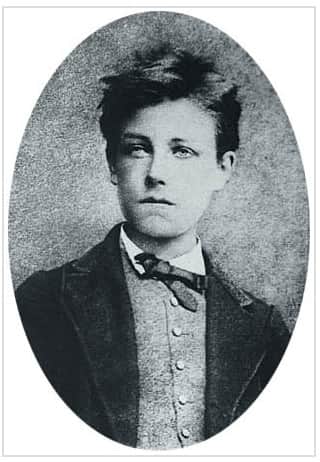

Nolan with him? I don’t think so. Not in love. Barrie was only here for a few weeks. Perhaps later on up in Queensland, but I don’t think so. No doubt Nolan was Barrie’s Verlaine. I suppose Barrie was a Rimbaud of sorts in search of a Verlaine, and he found him in a ten year older Nolan.

But Barrie was no Rimbaud – certainly not Nolan’s Rimbaud. Rimbaud himself was the only Rimbaud Nolan ever loved. Still …. he did paint Barrie in the same style as that Rimbaud photograph …

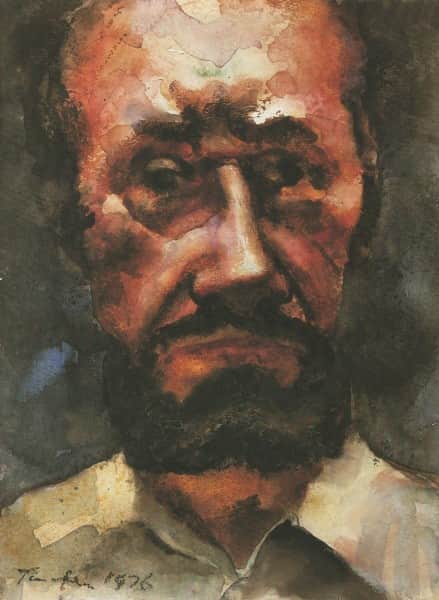

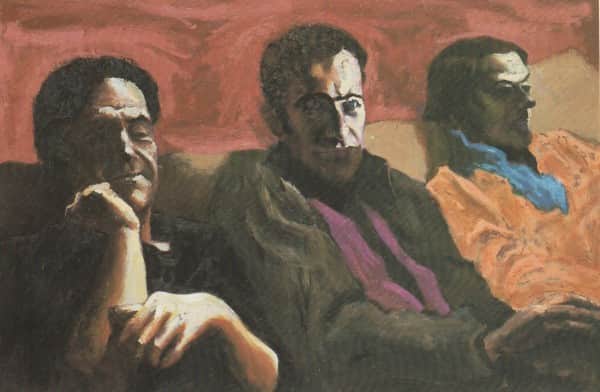

“Portrait of Barrett Reid”, Sidney Nolan, 1947, QAG collection

.

even down to the oval frame!

.

Arthur Rimbaud, photo by Etienne Carjat, Paris, October 1871

.

They wrote each other poetry. Nolan called him his prince. Barrie showed me a poem Nolan wrote to him, for him, just before he left. Prince on a Hill.59

And they wrote to each other afterwards …. Barrie begging him to come north and stay for a time.

And so it goes. And so Nolan went …. that July …. and never came back.

He stayed in Queensland about 5 months. Travelled around a lot. John and I sent him a cheque each month.60What captured his imagination completely was Fraser Island. He went there with Barrie.61

He wrote to us from the island and sent photos of his paintings. Small Box Brownie photos, black and white and hard to get a real feeling from.

.

Photograph of ‘Urang Creek’ (early version of ‘Mrs Fraser’), sent by Nolan to the Reeds from Fraser Island, 1947

.

One was about Mrs Fraser … she was shipwrecked up there and rescued from the aboriginals by a convict.

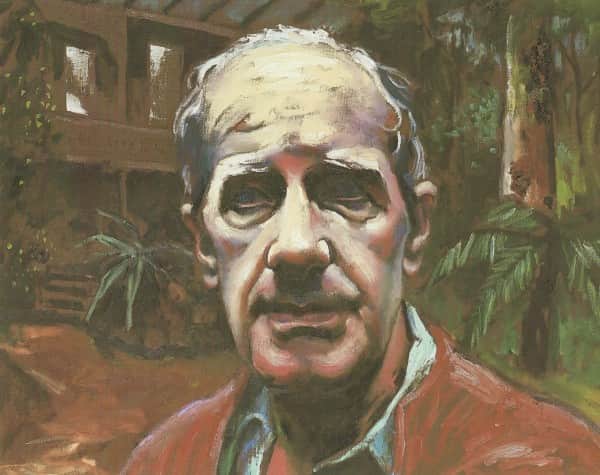

His Christmas gift that year was a Fraser Island painting … Lake Wabby …. quite beautiful, almost traditional. I still have it, treasure it ….it’s the last thing he ever gave me.

.

“Lake Wabby”, Sidney Nolan, 1947, Heide Museum of Modern Art collection

.

Something happened to the Mrs Fraser painting though. In more ways than one. I’ve never seen it, just photos in catalogues. It’s quite different to the photo he sent – he’s painted one of his oval frames around it and then cut off the top.62

.

“Mrs Fraser” 1947, Sidney Nolan

.

I saw a colour photo in a Swedish catalogue a while ago. It’s quite spoiled …. would have been beautiful once.

.

Sidney Nolan, “Urang Creek”,1947, computer enhanced reconstruction

.

The other thing that’s changed is that he and his scribes have managed to link me with Mrs Fraser and him with the convict who rescued her.63

She’s supposed to have betrayed Bracefell, that’s the convict, for not speaking up as she’d promised, to help him get a pardon. I’m supposed to have betrayed Nolan for keeping the paintings … and God only knows what else.

Ha. Hardly. As for Bracefell. I’ve looked into it. Bracefell didn’t even rescue Mrs Fraser. It was another convict …. Graham someone or other.

And as for the paintings. I did return them. All of them – except for the Kellys – and they were mine. He gave them to me.

All the others went back. Hundreds of them.

I’ll never forget them going. Barrie and John were packing them and I was distraught …. utterly distraught.64

.

RECREATING

.

They can’t go. They can’t. They can’t. Don’t take them. No. No. No. Don’t take them.

[SOBBING] You musn’t take them. Please don’t take them. Please …. please … please don’t take our paintings.

John. Leave them alone. John … Johnny. Please …. don’t take … them … please.

Barrie. Stop him. Barrie please …. don’t help him …. stop him.

Both of you …. stop …. taking …. our …. paintings.

Oh … please …. please.

.

(She wails … a shrill keening, and rushes out of the room. Her wailing/keening continues off stage. Her running frantic footsteps can be heard. She suddenly appears, arms scratched and bleeding … and stands stock still staring … slowly, focussing, she screams …)

.

No. Not that one. That is mine. He painted that for me.

.

“Rosa Mutabilis”, 1945, Sidney Nolan, Heide Museum of Modern Art collection

.

I planted that rose tree. He painted it … with me in it …. “I am the day, I am the dew; you, Lady, are the tree”.65 Nolan said that to me …. when he gave it to me. It is …. mine. It …. is …. my …. annunciation.

.

(She crumples)

.

Take them …. all right, take them. But not that one. Not Rosa Mutabilis. Rosa …. Mutabilis …. is mine.

.

TO HERSELF

.

(Absent mindedly she wipes the blood from her arms with a tea towel)

.

And I did throw myself onto the rose bushes. Again and again … until they restrained me. I couldn’t function. Not for hours …. for days.

First you left Nolan, then the paintings. Looking back …. yes …. the paintings going …. that was when everything … really began to empty out.

Only a few years later it was Joy. She’s been dead twenty years now, it must be … at least. The Hodgkins eventually had its way, although she and Gray got ten years more than they thought.

Dear Joy. You and Gray. God, what a time that was. That same Christmas …. everything seemed to happen around then. Bert was in Japan of all places …. not a good move.

He got back about March I think it was …. just after you’d met Gray Smith. You and Gray just clicked.66 I’d arranged for you to see a specialist about the cough and that nasty lump on your neck. And just then Bert gets back from Japan.

I wonder if you had a premonition about the Hodgkins. You didn’t even know the test results when Bert got back …. and you told him you were leaving, leaving him and Sweeney both, that same day. Poor little Weeno. And you did – you and Gray together, straight off to Sydney.

And when you found out about the Hodgkins, you were sure you’d done the right thing. You wrote asking us to adopt Sweeney. And we did eventually, a few years later – once Bert went to Europe and finally realised it would be better for Weeno to be with us.67

So I had a child of my own! At last … at long last.

.

(Long pause)

.

I still find it so difficult to talk about Sweeney. It’s two and a half years since you died Weeno.68

I don’t want to say too much. I can’t. I get too upset. And I know people blame me. At the funeral … I said to them …. “You blame me, don’t you.” It wasn’t a question.

My dear boy …. my poor, dear boy. I’ve come to think that all you really wanted was a mother and a father you knew. One mother. One father. Instead you had two mothers, Joy and me, and how many fathers? Three? Four?

Bert, John … Billy Hyde, that drummer who played at the Hotel where Joy worked. You knew the rumour. I even told you your father had died when I saw Hyde’s funeral notice a few years ago – that wasn’t very nice of me.69

And those blue, blue eyes of yours. Billy Hyde had blue eyes I’m told. But so too Nolan. And Nolan loved you Swene, didn’t he … that time over on Bellarine when you were just a few months old and Nolan carried you for ages and Bert took photos of us all.

.

Albert Tucker, photo of Joy Hester, Sidney Nolan holding Sweeney, John & Sunday Reed, Point Lonsdale, Victoria, 1945 or 1946

.

And that strange thing when you started up the gallery in Fitzroy. You told me Nolan said you could have First Class Marksman for the new gallery.70 Well, I knew you’d met Nolan when you went to London in the sixties …. and I’d never liked the painting anyway.

So I gave it to you Sweeney. And you sold it to McAlpine – which is why it’s not with the others in Canberra.71

Ah, the Kellys. That was another loss for me. A big loss – they’d been so much a part of me …. and him …. us. They went …. and four years later they’re back down the hill for a little bit longer. It’s a homecoming.

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

And Bob dying just before the Kellys went was a big loss. She suicided too. She was going to meet Nolan for arvo tea …. ha …. instead she booked into a hotel with a bottle of tablets.72 We’d hardly been in touch since she and Nolan got married.

But it was Sweeney’s suicide that emptied me out completely. He came out to Heide that Saturday morning.73 But we had no idea …. no idea. We should have known. That’s why I’m to blame. I should have known, but I just had no idea.

He was only 34 …. only 34.

.

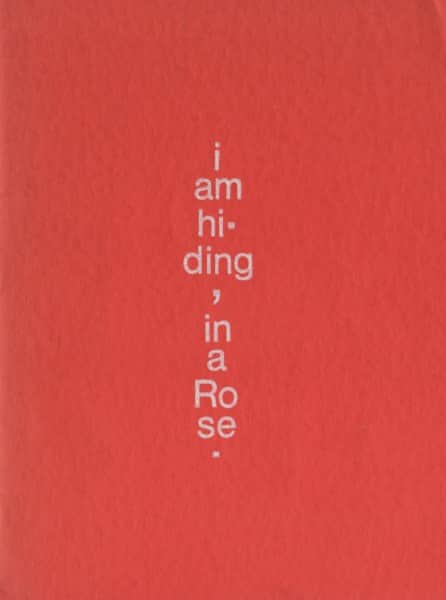

Visual poem by Sweeney Reed, c 1978

.

He loved Nolan’s Rosa Mutabilis. He wrote one of his visual poems about it …. i am hiding, in a Rose. We used it for the funeral book.

.

(Long heavy sigh)

.

Oh my dead dears!

.

(Pause)

.

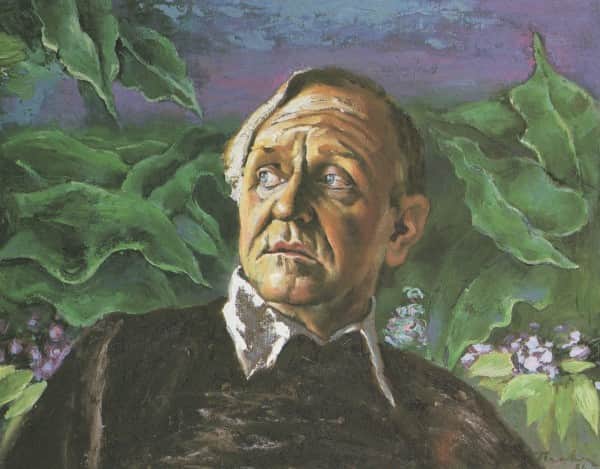

I’ll tell you about Nolan’s 30th birthday.74 He’d woken early, much earlier than usual, and he’d begun painting even before breakfast. I could hear him in the dining room scraping back. You hear everything in this old farmhouse. Ah Johnny, you knew that didn’t you!

I got up, threw on a dressing gown and slippers – his birthday’s late April so it was getting chilly – and I tippy-toed to the door and watched.

He was working fast – faster than usual – even for him. The board laid out on the old refectory table. I’m sure he knew I was there, but he didn’t say anything or turn around for a good twenty minutes.

Then suddenly he swung round on his heel, bright as a button, beaming smile … “Morning Sun. I’ll let you see this one later” and he stacked it face in against the wall. “When it’s finished. I’ve got to draw in a figure. It’s Watchtower …. the last of them.”75

He said I wouldn’t like it. “It’s a bit on the dark and gloomy side Sun” he said, “but don’t worry, I’ve got you a birthday present.” He was crazy like that Nolan – his birthday and I get a present.

“We’ll go down to the riverbank after lunch and read it together” he said. And then, “Bugger! Now you know what it is. I’ve spoiled my surprise.”

And that’s what we did. John had letters to write and stayed up here. And Nolan and I sat on the bank just near where he used to run down and jump in yelling like a banshee …. and we gazed down over the dull, brown, beautiful muddied old Yarra, and he gave me my present on his birthday. Dylan Thomas’ little book of poems Deaths and Entrances. I’ve still got it.

He wanted to read me Poem in October.76 Here it is … this is the book he gave me.

.

(She reads)

.

“It was my thirtieth year to heaven

Woke to my hearing from harbour and neighbour wood

And the mussel pooled and the heron

Priested shore”

.

What a marvellous poem.

And when he got to this part where Thomas speaks of childhood memories …. here, this bit:

.

“And I saw in the turning so clearly a child’s

Forgotten mornings when he walked with his mother

Through the parables

Of sunlight

And the legends of the green chapels”

.

When he read that he told me how his father lived at Shepparton when a boy. Later he’d take his own family back for holidays at Toolamba on the Goulburn River.

.

Daunt’s Bend, Goulburn River at Toolamba, Victoria

.

He and his father had their special spot – a bend in the river near the little township – they’d fish there for Murray cod. “It was like that Sun” he said, “just like that – parables of sunlight and legends of green chapels. It fits perfectly. Even down to my Uncle Bill, who was a legend with an axe.”

He talked about his own “child’s forgotten mornings” and he wept telling me about this special place … it was so moving. He painted the scene in words with that frightening clarity of his. “The light Sun, the light is transcendental” he said, “it completely defies description … you can only be part of it, you can only be within it.”

“Read the next verse Sun, and I’ll read the last.”

So I read:

.

“These were the woods the river and sea

Where a boy

In the listening

Summertime of the dead whispered the truth of his joy

To the trees and the stones and the fish in the tide.

And the mystery

Sang alive

Still in the water ……”

.

And he finished the last verse:

.

“O may my heart’s truth

Still be sung

On this high hill in a year’s turning.”

.

And as he finished it, our fingers touched, nothing more … and we sat there for ages, stock still, saying nothing, just gazing into the muddy waters …

Eventually we headed back to the house. And as we walked slowly up the hill I said to him:

.

RECREATING

.

You must paint it Nolan. Paint it. Paint it, yes – but not merely like that …. like you just described it. Yes, paint it as you SEE it – but more than that …. paint it as if you are a part of it.

How do I tell you? How to explain it?

Paint it as if you are integral with it, as if you could become the landscape. Paint that.

I’m not making sense, I know.

Yes. I do know. Remember that day at Merthon and I showed you the old magic lantern … the Praxi No Scope. Remember it had a cylinder with a strip of images on the inside.77

It’s simple Nolan. Don’t you see.

You paint it as the river itself would see everything – and you do that as if you’re sitting in the middle of a magic lantern cylinder with the images of the bank all around you. That is exactly how the river sees it.

And that Nolan, is how you paint parables of sunlight and legends of green chapels!

.

TO AUDIENCE

.

He didn’t say a lot as we walked back to the house that day. It was mainly me. Unusual for Nolan. But he must have listened because he said something about the river seeing it just like the waterhole must see the castle we painted into the Kelly landscape.

As we got up the hill close to the house … our hands brushed again … and he repeated those last lines of the poem:

.

“O may my heart’s truth

Still be sung

On this high hill in a year’s turning.”

.

Looking back, I’m not sure he had anything in mind. Perhaps. I don’t know really. By and large though, I think we were both more or less oblivious to what a year’s turning would bring.

But no doubt about it. In less than three months he was gone. And in less than a year he married Bob.

Well, you know just about everything else.

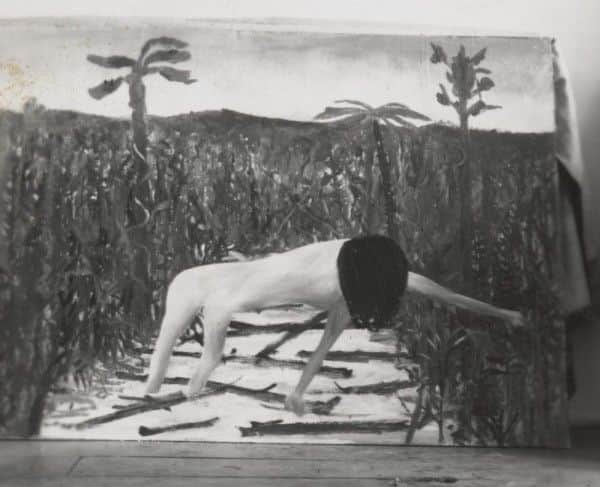

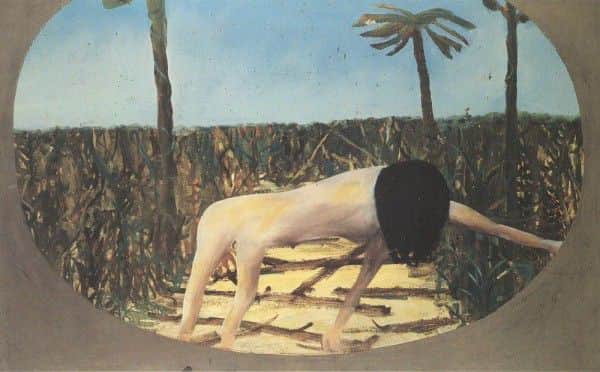

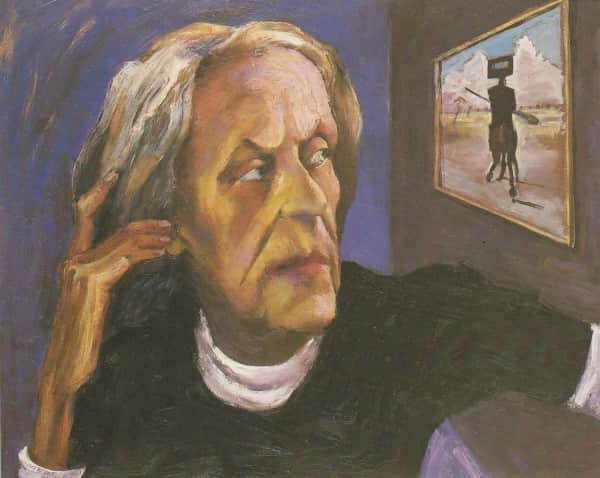

Except perhaps Paradise Garden (SHUDDERS). I’ll show you. It’s here. He sent me a copy.

How do I tell anyone about Paradise Garden? Well it’s a Nolan production from beginning to end. Poems by Nolan, drawings by Nolan, paintings by Nolan. A lavish publication from the private press of his friend McAlpine.78

And there’s even a film I’m told, but no one seems to have seen it – which is no bad thing because the poems are not very nice.79

Everything – the poems, the dreadful dreadful ugly drawings – are all about his time here at Heide. About us, about John. About very personal things, private things. It’s nasty, nasty. Barrie calls him “Herr Dr Conjurer” – and that about Nolan coming from Barrie tells you something!80

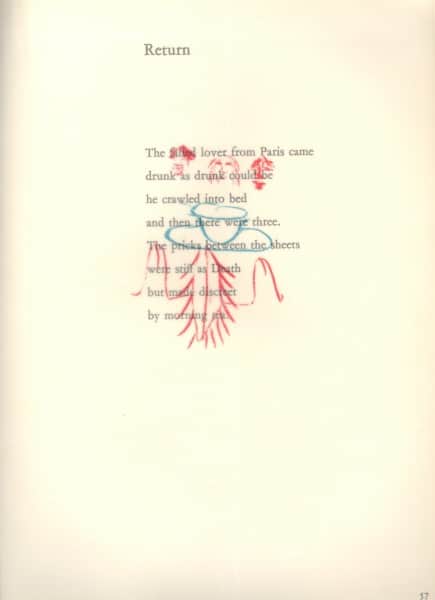

Here, I’ll show you. Remember that letter John wrote about Sam Atyeo coming back one night. Well look at this. He calls it Return81– this is what I mean. Listen:

.

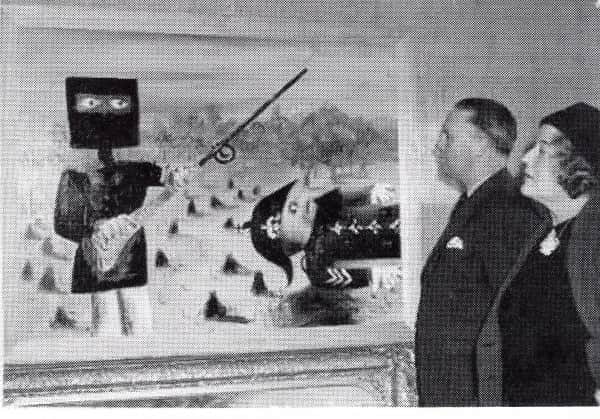

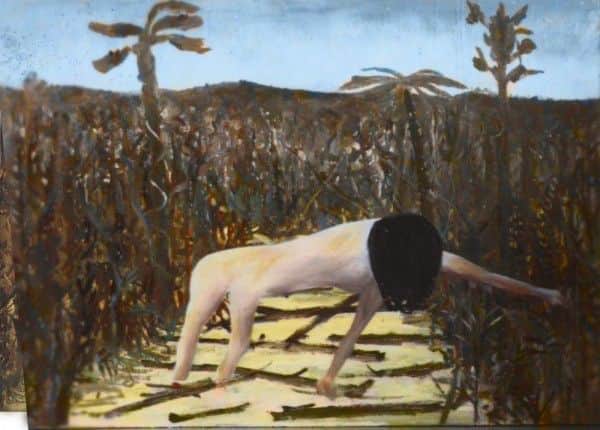

Sidney Nolan, “Return” from “Paradise Garden”, 1971

.

“The failed lover from Paris came

drunk as drunk could be

he crawled into bed

and then there were three.

The pricks between the sheets

were stiff as Death

but made discrete

by morning tea.”

.

And the drawing. Uuurrgh. Not the subject matter – but the quality of it all is just so much beneath him. It’s saddening.

And one called Permanent Erection. Uuurrgh. I won’t read any of them again. No I won’t …

.

So hurtful. So, so personal. Why would he write about that – and let his damn flunkeys write things like this. Listen: “Intercourse with her is a nervous disease. No retraction after orgasm. but an inflamed jutting forth. The poem describes a psychosomatic condition” That’s Robert bloody Melville in his essay Disquieting Muse – if you can call it an essay.82

And it’s rubbish. There’s a medical term for it – “penis captivus.” Psychosomatic condition. Ha. I didn’t have a psychosomatic condition. I had that botched up hysterectomy in Paris, that’s what I had.

And there’s lots more. Much more …. lots and lots …. (a sob) …. steeled by a noon whisky … I enter her old plumbing … 83

You bastard Nolan. You misogynist bastard. You’ve changed your tune, haven’t you No? You didn’t need any whisky to steel you back then, did you? …. my fine young cockaloram …. my green lad moonboy lover?

.

(She shudders – then a long pause)

.

But I never could work out why. Suddenly, almost out of the blue, all those years later. Suddenly this.

I think this notion about the artist’s muse – the disquieting muse – had a lot to do with it. Muses after their time are like prophets in their own land – not welcome.

There was something too I did, quite unwittingly …. it could have sparked off that train of thought for him. And there were other things he probably blamed me for. But first I’ll tell you what I did.

It’s easiest to just read the letter.84 It was 1967 or 68, just a few years before he came up with Paradise Garden. I‘ve only written him two letters since he left, this one ten years ago …. longer …. and the one last week.

.

READS FROM LETTER

.

“Dear No” I began. Ha. I remember wondering how to begin. It was twenty years since he left. I could hardly have begun “My darling Cock, Robin”

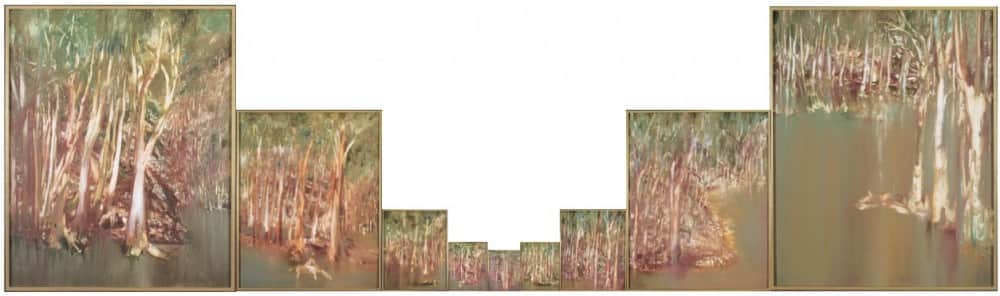

“Dear No. This is to tell you I have just seen Riverbend85 and to tell you that it is magnificent. Truly magnificent. It took me to a place no work of art ever has, before or since.

.

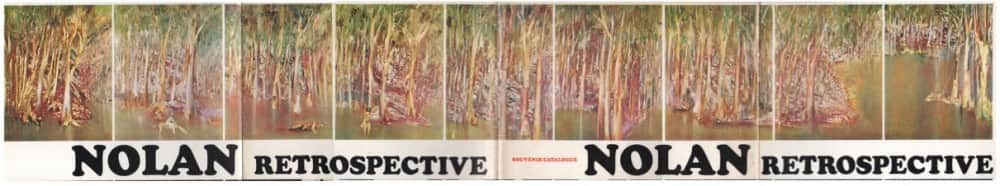

“Riverbend”, 1964-65, Sidney Nolan. Note that the size of the middle seven panels has been progressively reduced in this presentation.

.

Of course I recognised it immediately from the time we sat on the riverbank at Heide on your 30th birthday. Parables of sunlight and legends of the green chapels.

When we walked back up the hill that day… remember how I told you to paint it as the river would see it. Sit in the magic lantern, I said, with the images all around you. And that’s exactly what you’ve done.

I hadn’t intended to visit your big 50th birthday retrospective. Not because of anything you’d said or done – or hadn’t done. Rather because seeing your work, old or new, makes me so desperately sad. Sad for what we lost, sad for everything we could have done … I could have done …. with you, for you. And sad for all the art never made as a consequence.

But when Barrie showed me the souvenir catalog with the nine Riverbend panels stretched back and front across the double folded cover, I knew I had to see it in the flesh. I’ve been in this afternoon and I’m writing this straight away back home at Heide.

I remember that afternoon how you told me your boyhood river had a heavenly transcendental light. Well Riverbend has that No, and more. I was mesmerised. It transports you to another place …. another plane …. another dimension.

I once said to you – it may even have been the very first time you visited Heide with John so long ago – I said that art must challenge and inspire. I probably said uplift too. But it surely is rare that art is at once transformative, transforming, transcending, and transcendental.

Riverbend is all of that. It is surely your greatest work. It eclipses our Kellys. Each of the nine is a masterpiece in its own right – but together …. the whole work is like the place must be itself, beyond words.

As soon as I saw the catalogue I opened the cover right out.

.

Detail, cover of catalogue, “Sidney Nolan retrospective exhibition: paintings from 1937 to 1967”, 1967, AGNSW

.

I folded it round in a circle, outside-in, until the first and last images met and formed a cylinder. And sure enough, they aligned. It was one big continuous panorama. You were inside the magic lantern.

.

Simulated Praxinoscope strip of Sidney Nolan’s “Riverbend”

.