THE BECKONING

– a short story blending fact and fiction –

<> <> <>

Their honeymoon began rather ordinarily. They’d had to wait a week which didn’t please her any more than him, but she’d never been much good at maths and had got the dates wrong.

Then there was the train trip. Why train for goodness sake, she would ask her visitors years later, why not a hire car? The question betrayed her wavering state of mind and her scant recall of how few were the transport options back in 1936 for her August wedding.

Not forgotten though was its eventual consummation up on the north shore beach the night they camped by the coloured sands. And she remembered all too well the sand invading their nuptial couch. Neither had she forgotten the white dingo – if dingo it was. She would never be quite sure.

<> <> <>

The mountains of Mourne sweeping down to the sea in County Down were unseen by John Graham in 1824 when, shackled in the back of a prison cart under watch of the Royal Irish Constabulary, he travelled to the Dundalk assizes. There, five feet tall and tried for the theft of six pounds of hemp, the little Irishman was sentenced to seven years transportation.

Twice seven was the lot of David Bracewell, a cockney from Shadwell on the banks of the River Thames in London’s East End. As set down in the official record of court proceedings at the Old Bailey in 1826, he received fourteen years despite failing in his attempt, ‘a watch to the value of 20 shillings violently and feloniously to steal’.

Another ten years, and these two convicts would have much more in common than their exposure to the vagaries of British justice. The likes of Eliza Fraser for instance, a braw Scots lass from Orkney. With her they would share experiences none of them could once have imagined.

<> <> <>

A fisherman had driven them in his old utility along 40 miles of pristine beach, unmarked, so it seemed, by human let alone tyre tread. He would pick them up next morning on his return.

Memory of that drive would be almost her last vivid recollection. The blue of the ocean to the right, flecked at its margin by a surf that at times could sweep right across the wide ebbtide sand extending ahead in a long gentle arch.

To the left, the littoral – first low scrub and sand dunes, then a more pronounced line of hills with a long wide gully, inviting of visitors, where the escarpment tumbled abruptly to the beach in a cascade of coloured sands.

<> <> <>

No visitors came to Cork harbour where at His Majesty’s pleasure, if not his own, John Graham waited in the rotting hulk of an old warship, his floating prison. From it he was transported to the penal colony of New South Wales, where chained in the hold of the ‘Hooghly’ as she sailed through the Heads, John was oblivious to the magic of Sydney harbour, its waters more his keeper. As also was the Parramatta mill owner to whom he was assigned as labourer, and against whom an act of petty larceny doubled his sentence to fourteen years – not to be served in Sydney, but rather at Moreton Bay Convict Settlement, the latest outpost of despair and privation.

Nor were there visitors to the hulks on the Thames where David Bracewell awaited his passage to penal servitude. Immediately his ship the ‘Layton’ arrived in Hobart, it was to the Moreton Bay hell hole Bracewell’s bad reputation saw him consigned. His gaoler’s report bluntly stated “In gaol before, bad” and a character report from the hulks opined “Mutinous, very bad fellow.”

By the time David Bracewell arrived in Brisbane Town in late 1827, John Graham had already escaped a regime unimaginably brutal.

<> <> <>

Their lovemaking had been an immersion, each in innermost depth of other, their very souls seemingly one. So they thought as they moved in the moonlight toward another immersion where the stream of fresh water seeping from a spring behind the dunes entered the ocean, and where the surf could wash the invading sand from their bodies.

It was walking back across the beach they first sighted the dingo. Unlike any other dog they’d ever seen, and much larger, it stood in the little stream and surveyed their approach, as like a human kneeling as an animal standing. In the moonlight its coat, perhaps it was skin, appeared pale cream with greenish hue – like a cadaver, he would come to learn.

Stock still in the stream, its head a mass of dark hair, the creature extended a limb toward them, seemingly in welcome, beckoning almost beseechingly.

<> <> <>

<> <> <>

Chained by day and locked up by night, the convicts worked from dawn to dusk with just one midday break. The slightest insubordination would provoke a flogging with the cat-o-nine-tails, a vicious flail having nine knotted leather braids woven into a springy handle and all kept well oiled in a leather bag. They soon learned little was needed to let the cat out of the bag.

Their souls seared and their backs scarred by the lash, many convicts attempted escape. However the sea to the east and mountains to the west were formidable barriers, as were the fearsome ‘natives’ populating the coastal plains to south and north. Regarded as savage cannibals, they demonstrated a hardly surprising reluctance to depart their land and lifestyle.

Most escaped convicts returned voluntarily from the terrors of the bush or were recaptured. More than a few were killed by the first people. Some though, a mere handful, were recognised as white-skinned ghosts of dead relatives and welcomed. John Graham and David Bracewell were two such ‘white blackfellas’.

<> <> <>

When was it that things first began to go wrong for them? She certainly never seemed herself after the child was born. Most likely it was post-natal depression, not then an expression used or a condition treated.

Once war was declared he didn’t wait to be conscripted. Against her wishes – she would never manage their young son in her fragile state, she pleaded again and again – he enlisted. It was early in May 1940, just after the boy’s third birthday. Why, she asked, why? He couldn’t have said why himself at the time. Later he would realise it was much less an act of patriotism than an escape from her increasing emotional fragility and unpredictability.

In stark contrast, his strength, fearlessness and incisive initiative quickly marked for him an army life different to most. He became a commando and by the boy’s fifth birthday was in secret training at the Commando School on Fraser Island.

<> <> <>

When an Aboriginal woman recognised him as her dead husband, John Graham lived with her people for several years, learned their language, how to hunt and fish, and became thoroughly familiar with their land and customs. On her death he returned to Moreton Bay, only to learn he had to serve out the entirety of his sentence.

David Bracewell absconded no fewer than four times, each recapture rewarded with increasingly severe floggings. His last 150 lashes steeled a resolve to escape one final time and never return.

In 1836, when John volunteered to guide a party of soldiers and convicts to find and ‘rescue’ a white woman from the clutches of ‘savages’ who ‘held her captive’, David was living among them.

<> <> <>

She didn’t cope at all with his absence. She couldn’t think or concentrate, couldn’t even remember whether she’d fed or bathed the child. One day her mother had to retrieve them from town when a neighbour reported she’d boarded a tram in her nightdress with the boy still in pyjamas.

Her dreams became worse. Particularly the one with the dingo. Although the medication helped, it only worsened other things. She would doze off completely. One day she woke in panic to a knock on the door by the man at the corner store, who realised things were amiss when the youngster came in with a five pound note to buy a threepenny icecream.

She shouldn’t have taken the tablets the day they went to the swimming pool. It was so difficult to wake her – so much better had they not. “Why dear God, did they wake me?” She could never understand why and would repeat over and over “why … wake … me?” As years passed it became her mantra.

<> <> <>

Bound for Singapore and thence London, in 1836 the heavily pregnant Mrs Fraser set sail from Sydney with her husband James aboard his brig ‘Stirling Castle’. Their progress rudely interrupted by a reef off the Capricornia Coast, they abandoned ship and took to the longboat with ten crew and made south.

Six weeks later they cast up on a beautiful sandy beach, now called Orchid, on the northern shores of the world’s largest sand island which now bears their name and, more recently, the name given by its own first people …. K’gari.

In the long boat she had given birth to a baby boy who died soon after, drowned in unbailed seawater.

<> <> <>

His numbed reaction to their son’s drowning, and the indecision it induced, combined to end his time with the commandos of Z Special Unit. It meant he could not join their attacks on Singapore Harbour, either to return triumphant with them after Operation Jaywick, or a year later to die with them on the failed Operation Rimau.

In time he wondered whether it was this he was unable to forgive her, rather than his son’s death.

He nevertheless saw much action in the regular army, and much death. Every glimpse of a blueish-green corpse brought to mind his drowned son, and also the creature they saw the night he was conceived.

<> <> <>

Unable to relaunch the longboat, the castaways set off south along the beach – the fearsome otherness of the ‘natives’ giving way to existential necessity.

They bartered their way south until equipment and clothing were as exhausted as the patience of their aboriginal hosts, who saw these boat people as completely lacking a self-sufficiency they took for granted and their ancestors had known for millennia.

Stripped of clothing, the refugees shouldered the workload of what seemed to them a primitive day-to-day existence.

<> <> <>

After the war they tried hard to make the marriage work. He wanted to show her Fraser Island, show her the lake into which they parachuted, show her the long curving jetty from which they jumped naked, and most of all show her the little creek at the Forestry settlement. He thought its waters the purest he’d ever seen. If they washed there, somehow …. surely …. he thought, they must heal.

They went to the island in late 1947. An artist there reckoned it was impossible to tell where the water meets the sand, saying “your feet find themselves in water but your eyesight swears you are still walking on sand.”

Casualties of their times and of their lives, they made love for the first time in a long time – right there, in the noontime primeval waters of the creek. Both swore they had opened eyes shut in passion to see the dingo beckoning them, just as it had eleven years earlier.

<> <> <>

Travelling along the island, the aboriginal women realised the white woman had recently given birth. Still lactating, she was given a sickly child to suckle.

They took her then to a special woman’s place. There, in a clearing surrounded by trees and ferns, they bathed her in a stream of water more pure and more clear than she had ever seen before – even on Orkney. Calling the setting Woongoolbver, they coated her with grease and marked her with ochre.

After weeks of hardship, Mrs Fraser and five others were canoed to the mainland. Another five, including her husband, had perished on the island.

<> <> <>

The artist they’d met on the island was Sidney Nolan. He later sent them a personal invitation to see the exhibition of his Fraser Island paintings and, five months pregnant, she reluctantly braved Brisbane’s fierce February sun.

There were only a dozen, downstairs in a basement, each on its own easel and arranged in an arc.

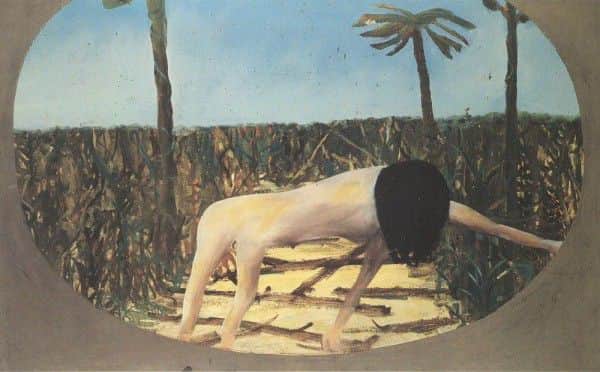

One work stood out. Named Woongoolbver Creek in the catalogue, it showed their dingo, if dingo it was, standing in water so clear you had to look close to be certain a creek was there. Head covered by hair and outstretched arm beckoning, the creature’s sallow cream coat (or perhaps it was skin) seemed mottled with blueish green. It led their thoughts to a dark, dark place.

<> <> <>

“Mrs Fraser” (initially called “Woongoolbver Creek”) 1947, Sidney Nolan, collection QAGOMA. The preceding black and white photograph of the original version was taken by Sidney Nolan on Fraser Island in 1947

<> <> <>

And so the convicts and Eliza Fraser met. She with strong motive to return to civilisation, they with motive just as strong – to receive a pardon.

Most likely they collaborated; David to take her from a woman’s camp to a corroboree ground near today’s Lake Cootharaba, John to walk 20 miles along the beach to a gully near a patch of coloured sands where fresh water trickled to the surf.

At the corroboree ground the two would liaise, and helped by their aboriginal families, paddle Mrs Fraser across the lake. Here David hesitated, and John alone would lead her through the gully to the small party of soldiers and convicts who had followed him along the beach and were waiting at the coloured sands.

<> <> <>

It was Eliza, for so they named the daughter conceived that day in the clear creek waters, who years later would identify their drowned bodies.

First his, found floating face down beneath Mackenzie’s Jetty near the mouth of Woongoolbver Creek close to the scant remains of the old Fraser Commando School. They said it was heart attack.

Then a year later, hers, snagged on rocks beneath the William Jolly Bridge a week after she went missing from the hospital at Goodna. A trusted and unlocked inmate for many years, she eluded vigilance one moonlit night. It could have been her, an enquiry speculated, seen crawling naked through the paddocks towards the river, one arm outstretched.

<> <> <>

Thus was Mrs Fraser ‘rescued’. She remained at Moreton Bay for several weeks recovering from her ordeal and was taken to Sydney where she soon married another ship’s captain. She sailed with him to London and thus began her transition to myth and legend.

John Graham too went to Sydney, received his pardon, was awarded ten pounds, and quite unlike the woman he had found, disappeared from history.

David Bracewell remained with his Aboriginal family until ‘rescued’ in 1842. Accidentally killed soon after when felling a tree on Woogaroo station near Ipswich, he was buried in Brisbane’s first cemetery.

<> <> <>

Eliza is uncertain just when her own last journey began. With her diagnosis perhaps, or was it earlier with their bodies? Was it her discovery of the unfinished manuscript, or was it with her resolve to complete the short story her mother began years before in Goodna?

Perhaps it was in 1995 when she first saw Nolan’s painting Mrs Fraser, newly acquired by the Queensland Art Gallery, and realised from her mother’s description that her parents had seen it almost fifty years earlier. Then called Woongoolbver Creek but later renamed, cut smaller, given a lower skyline and an ugly painted oval border – the one constant remained the animal-like creature at centre stage.

Or perhaps her journey began when her studies of our first people taught her that Woongoolbver Creek was where women traditionally gave birth because of the purity of the water, where men were forbidden, and where a woman was marked in ochre to warn the men she was not to be touched.

Did it begin when she learnt that Woogaroo station, where David Bracewell was killed, eventually became the Goodna Asylum – her mother’s home for too many years? Or was it when she discovered that Brisbane’s long since overbuilt first cemetery, where David was buried, was on the riverbank where the William Jolly bridge today disgorges its traffic from beside the Art Gallery across the river?

Eliza was given to visiting this place where her mother’s body washed up. Perhaps her journey began the moonlit night she was there and saw a large dingo, if dingo it was, trundle across the bridge to sit beside the fountain in the small park now astride the old cemetery.

<> <> <>

But wherever it began, now that she has completed her mother’s short story, Eliza knows where her journey might well end.

When it seems the right time, perhaps if she were yet again to leave remission, she might drive along the beach above Noosa, its sand highway resurfaced hard and flat with each tide and today emblazoned with speed limit signs. She might stop where the escarpment collapses to coloured sands marking the gully between beach and lake, where today hang gliders launch from a platform atop the sanguine sand cliffs.

She’ll camp some distance from the gully, beside the little spring where the brother she never knew was conceived, and where exactly a hundred years before her parents’ honeymoon, David Bracewell probably hid as John Graham and her own namesake Eliza emerged from the scrub.

Next morning, if she feels well enough, she’ll retrace their paddle across Lake Cootharaba from the corroboree ground, and their walk through the gully to the beach.

<> <> <>

Then finally, she might return to K’gari. Hardly a return, for she has never really been there – except in utero, and that only just!

At the ancient birthing place by Woongoolbver Creek, on a cold winter night beneath a full moon, she can imagine removing her clothes and immersing her emaciated body in the cool clear waters. It would be a purification.

But she will not depart until the dingo, if dingo it really is, appears and reaches out to her …. beseechingly …. beckoning.

<> <> <>

Aquis submersus