ABSTRACT.

Sidney Nolan’s 1947 painting Mrs Fraser, now in the collection of the Queensland Art Gallery, is one of his best known works. I recently discovered an image of a companion work, along with images of several other hitherto unreported works from the February 1948 exhibition of twelve Fraser Island paintings at Moreton Galleries in Brisbane. There now remains just one of the dozen with no known image.

Sidney Nolan, Fraser Island painting 1947, probably “Urang Creek”, whereabouts unknown

BACKGROUND

Sidney Nolan turned 30 on 22 April 1947. His twenties had been dominated by his time at Heide, the old farmhouse on acreage at Heidelberg outside Melbourne where John and Sunday Reed lived. She the daughter of Melbourne’s prominent and prosperous Baillieu family, he the Cambridge-educated lawyer son of a wealthy Tasmanian pastoralist, they had wealth allowing them to indulge their passion for modernism. Heide became home and haven to a procession of avant-garde artists, and the Reeds not only bought their works, but mentored and financially supported them.

Nolan is the artist most associated with Heide. Born in Melbourne in 1917, he lived in bayside St Kilda where, the son of a tram driver, his education was basic. At age 14 he left school to commence a design and craft course and then worked with a firm of hat makers for six years. In 1934 he commenced art school night classes at the National Gallery of Victoria and four years later, not long before he married Elizabeth Paterson, one of his fellow students at the Gallery Art School, his search for a measure of financial security brought him into contact with the Reeds. Nolan was just 21 and his meeting with the older couple would redirect his life. He spent more and more time at Heide and he and Sunday became lovers. Soon after the Nolans’ daughter was born early in 1941, Elizabeth told Nolan that the marriage was finished and when she refused to relent, in due course he moved in at Heide.1

In 1946 the Reeds holidayed in Queensland where they met Barrett (Barrie) Reid, editor of the Brisbane little magazine Barjai. At their invitation he visited Melbourne for Christmas, stayed at Heide and established a strong rapport with Nolan who was then in full swing completing the Kelly paintings. According to Reid, “as the four of us walked over the paddocks, Nolan talked of poetry, of rhyme and image and metre, and for a long time it seemed we never stopped talking.”2

By his thirtieth birthday Nolan’s world of the past several years and his life at Heide were falling apart. Before returning to Brisbane, Barrie Reid had suggested to Nolan that he should come north for a period,3 and finally, amid much inner turmoil, he decided to move on.4 He flew to Brisbane on 13 July 19475 and stayed in Queensland for five months. He would travel far and wide, but Fraser Island in particular would captivate him more than anywhere else. He first visited late in August for a few days with Barrie Reid and then in early October with poet Judith Wright and her husband Jack McKinney.6 This second time he would stay on by himself for a month and produce a dozen paintings, arguably, as a body of work, unlike anything else he ever painted.

THE MORETON EXHIBITION

Nolan’s northern excursion ended when he flew to Sydney on New Years Eve having arranged with John Cooper of Moreton Galleries to exhibit his Fraser Island paintings in February. Although passing mention appears in the literature of two other exhibitions of Nolan paintings during his stay in Queensland – one in the Ballad Bookshop, the other under the auspices of Miya Studio7 – the exhibition in The Moreton Galleries in the basement of A.M.P. Chambers in Edward Street from Tuesday, February 17th to 28th, 1948 was Nolan’s first in a commercial gallery.

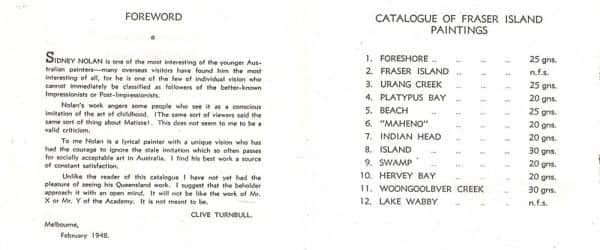

Sidney Nolan, Catalogue of Fraser Island Paintings, The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, February 17th to 28th, 1948

NOTE that since this article was posted in 2014, further information has come to light regarding the history, identity and whereabouts of a number of the paintings mentioned here. Consequently a little updating is necessary. However rather than editing the existing article, a short summary is provided in this endnote.8 It is suggested that this endnote be read before continuing, so that the sense of the original can be retained whilst allowing it to be read in light of this further information.

The Moreton Exhibition was hardly a success. Only one painting was sold by the gallery itself and the exhibition was lampooned by public and critics alike. Today no more than three or four of the paintings are at all well known, although the following trio are among Nolan’s better known works.

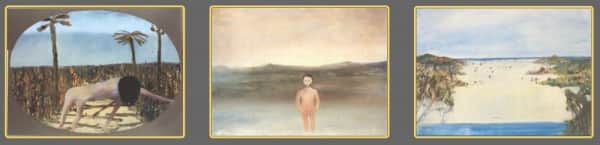

left to right: Sidney Nolan’s “Mrs Fraser”, Queensland Art Gallery; “Fraser Island” Art Gallery of New South Wales; “Lake Wabby”, Heide Museum of Modern Art

These three are also most likely the only paintings Nolan parted with at the time of the exhibition.9 The painting now known as Mrs Fraser most likely appeared in the Moreton exhibition as Swamp10 which was the only work purchased off the wall and was owned by Brisbane medico Dr Leopold Lofkovits. This sale of 20 gns, and a subsequent payment to Nolan of 15 gns, are recorded in the Moreton Cash Ledger.11 The ledger does not identify which painting was sold, but we can assume it was Swamp because a year later the regular Courier-Mail art panel of three or four works chosen to hang in the Queen Street vestibule of the Courier-Mail building included “The Swamp by Sidney Nolan (N.S.W.) … lent by Dr. L. Lofkovits.”12 Judith Wright and Jack McKinney probably purchased Fraser Island from Nolan direct13 which accounts for it being marked not for sale in the catalogue. Lake Wabby, the other n.f.s. designation, was Nolan’s 1947 Christmas gift to Sunday Reed. Nolan eventually re-acquired both Mrs Fraser and Fraser Island,14 and they would remain with him for the rest of his life – his Estate selling Mrs Fraser to QAG in 1995 and Fraser Island to AGNSW in 2001.

Two landscapes from the exhibition have appeared at auction over the years. In August 2013, QAGOMA purchased Platypus Bay for $94,550 inc. premium against an estimate of $35-45,000 at a Bonhams auction of early works from the Nolan Estate;15 the second work below, described as “inscribed with the title Frazer (sic) Island centre left,” was auctioned by Christie’s in 1999 and fetched $65,000 Hammer against the estimate of $30-50,000.

left to right: “Platypus Bay”, Queensland Art Gallery; work described as “Frazer (sic) Island”, whereabouts unknown

I became interested in the Moreton exhibition when researching in the Reed archive at SLV, and quite by chance stumbling on two black and white photos of Fraser Island paintings sent to the Reeds by Nolan.16 The discovery prompted an article reconstructing the well known Mrs Fraser to its initial version and deconstructing the common if incorrect belief that he had painted the work with intentional malevolence directed toward Sunday Reed.17

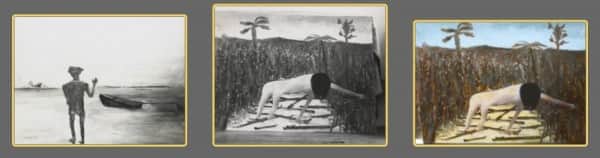

left to right: two photos of Fraser Island paintings, sent from the island by Nolan to Sunday Reed in 1947; computer enhanced coloured reconstruction of second photo

One other image of a work from the exhibition is on the public record. Labelled as The Beach, it was printed in Brisbane’s Courier-Mail newspaper along with a number of letters to the editor, including one from Judith Wright, responding to E.C.W.’s scoffing critique a week earlier.

The Courier-Mail, Brisbane, 19 February 1948

THE MISSING WORKS

With images of seven of the Moreton works known, I had hoped that inspection of the John Cooper papers at the Fryer Library, University of Queensland, would reveal the missing five. Whilst I did find some photos of the Moreton exhibition,18 the quest fell tantalisingly short of being complete.

In 1948 the dozen Moreton works were mounted for exhibition on easels and it would appear that three photos, each of a group of four paintings, were most probably taken. However only two of the three remain, and from what we already know of the works in the exhibition, the missing set would have included Lake Wabby, Swamp, Beach and one other. The absence of this third grouping is doubly frustrating; it means that one image remains unknown, and it deprives us of the certainty of knowing the exact format of Mrs Fraser/Swamp when first hung.

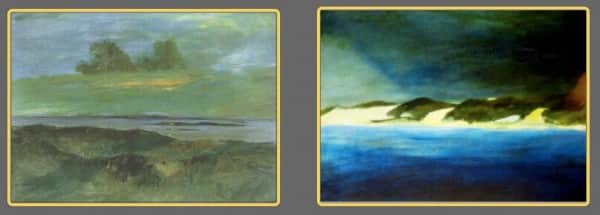

The two remaining photos of the sets of four are seen below. They reveal four new works: the Mrs Fraser image in the first photo, and the 1st, 2nd and last painting in the second set.

Sidney Nolan, 4 of 12 Fraser Island paintings exhibited at The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, 17-28 February 1948.

Sidney Nolan, 4 of 12 Fraser Island paintings exhibited at The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, 17-28 February 1948.

Squared-up images of each of the four new works appear below. The identity of three of the four has been suggested with some small basis for confidence. Their whereabouts are unknown.19

Sidney Nolan, Fraser Island paintings exhibited at The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, 17-28 February 1948. (L) possibly No 3 “Urang Creek”; (R) possibly No 10 “Hervey Bay”

Sidney Nolan, Fraser Island paintings exhibited at The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, 17-28 February 1948. (L) identity uncertain; (R) possibly No 6 “Maheno”

The dozen paintings comprise a unique set in more ways than one. They appear to be all the same size – certainly those in the two photographed sets of four are, and we know the exact dimensions of one work in each, Platypus Bay and Fraser Island, which are almost the same at 76 x 105 cm – as is Lake Wabby and would have been Swamp before it was cut down to the size of Mrs Fraser. These proportions are the same as can be scaled in the newspaper reproduction of Beach. It is certain therefore that ten of the twelve works are the same size – 30 x 42 inches in the old Imperial scale – and that Beach is probably also this size. We cannot be sure of the size of the painting which remains without an image. The known works are all painted in Ripolin on Masonite board.

The 30 x 42 inches board size is produced by cutting a 5 ft x 7 ft sheet of Masonite into four. Standard Masonite sheeting at the time did not include a 5 ft x 7 ft sheet and larger 8 ft x 6 ft sheets, when cut into 30 x 42 inch boards, would leave waste (it is not for nothing that so many of Nolan’s early works on Masonite are 4 ft x 3 ft). When Nolan visited Fraser Island in 1947 it is highly likely the World War 2 Commando Training School near Mackenzie’s Jetty a few kilometers south of Urang Creek was still in place. The standard P1 army hut had a 7 ft 4 in ceiling height and a space of approx 5 ft from the end wall to the first window. Although the Australian huts were usually unlined, it is tempting to speculate that the boards for these Fraser Island works just might have originated with the Army, from which in 1947 Nolan was still to be dishonourably discharged for going AWL in 1944.

Whatever their origin, I can find no records of any other Nolan works, at any time, on the 30 x 42 inch boards used for the Fraser Island works at Moreton Galleries. They appear to be quite unique.

POEM IN OCTOBER

An article entitled Poem in October is currently in preparation and should be posted on this website during 2014. In the context of the Dylan Thomas Poem in October, this article will look closely across the full sweep of Nolan’s experience of Fraser Island, the Moreton galleries Exhibition and the way his Fraser time impacted his relationship with Sunday Reed over the years.

On Fraser, amid new-found parables of sun light, he would paint his own Poem in October. Nolan had just turned 30 and at least in the sense of the poem, like Dylan Thomas, it was his thirtieth year to heaven. He could well marvel his birthday away …. but had the weather turned around?

He could little have realized that on another metaphorically high hill in a year’s turning he would gaze back on a year that had seen his connection with the Reeds permanently rupture, had seen his first one man show in a commercial gallery, had seen the first exhibition of the 27 Kellys, and had seen him marry John Reed’s sister Cynthia. All in all – some turning! We may well ponder how the following slightly altered last words from Thomas’ poem might apply to Nolan: O was his heart’s truth / Still sung / On this high hill in that year’s turning. The heart, according to Pascal, has reasons that reason knows not, and it is tempting to conclude that Nolan’s heart’s truth at that time would remain with him, in spite of many purgings, all his life.

The article will also examine in some detail each of the works, much in the manner of the following discussions on Urang Creek and Platypus Bay.

Urang Creek

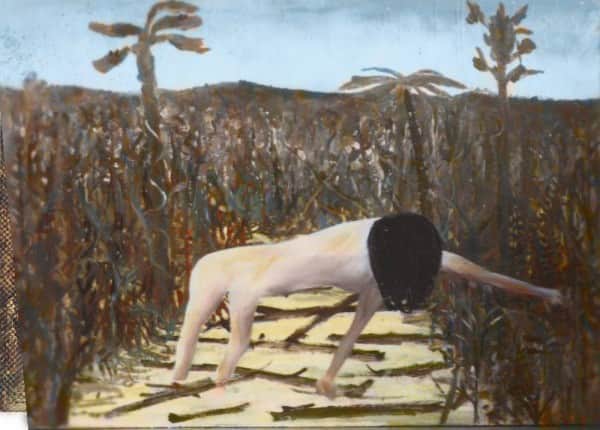

Sidney Nolan, Fraser Island painting 1947, probably “Urang Creek”, whereabouts unknown

Eliza Fraser stepped onto the island now carrying her name in late June 1836 with her husband Captain James Fraser and 10 crew who had sailed and rowed the Stirling Castle’s longboat 400 kilometers from where it wrecked on Swain Reef on 22 May. In spite of fearing the natives whose fires they saw, they put ashore on what is now Orchid Beach above Waddy Point to replenish their water and repair the leaking vessel, with the intention of sailing on to the safety of the penal settlement at Moreton Bay. Their real problems began when they were unable to relaunch the longboat which had become firmly stuck in the sand after days of high tides and bad winds. With no choice but to walk along the beach, they met up with groups of aborigines and bartered their way south until their equipment and clothing became exhausted – as did the patience of their aboriginal hosts who saw these white ghosts as completely lacking the most basic skills for a self-sufficiency they and their ancestors had known for millennia.

The white men and Eliza were stripped of their clothes and naked, were forced to shoulder the workload of a primitive day-to-day existence in which, in a reversal of the biblical fate of the dark-skinned Gibeonites, they became the hewers of wood and drawers of water. Eliza was made to nurse a sick aboriginal child, search swamps for fern roots, and goaded with fire-sticks, climb trees in search of bush honey. Badly sunburnt, with little food, she was forced to sleep without shelter and ‘punished’ in accordance with local custom when seen to be uncooperative.

Five of the group, including Captain Fraser, perished in the several exhausting weeks it took to reach the mainland at Inskip Point near the southern tip of the island. Today at Inskip, barges load 4WD vehicles for ferrying across the narrow passage to Fraser where they drive north along the beach and reach Orchid Beach in less than two hours. Eliza must have pondered how different her life would have been had that longboat not been washed so high onto the beach!

Her time on Fraser Island itself is largely undisputed20 and was known to Nolan by the time he first visited the island in August 1947, when he most likely landed at the log dump at Urang Creek.

He and Barrie Reid had sailed on a timber logging barge down the Mary River from Maryborough, through the River Heads into the lower reaches of Tin Can Bay inlet and out across Hervey Bay to the west coast of the lower half of Fraser Island where they spent the night waiting for the flood tide to float them into the shallow waters of Urang Creek.21 First light would have revealed the wreck of the SS Essex. Run aground at the mouth of Urang Creek on a king tide during the war, local legend has it she was beached to avoid being requisitioned by the navy. Still there today, she is gradually losing her battle with the mangroves growing through her hull. As the tide runs out Urang becomes ‘a shallow small creek that completely dries at low tide. The grey sand in the creek bed has the consistency of mud, and is not friendly to walkers. The log dump, a wharf ramp of logs laid in the white sand, lies 80 meters away ….’22

Urang Creek, Fraser Island, looking upstream at high tide

The comparison below of the Nolan image, Little Woody Island seen in the background, with the real Urang Creek brings a reality and poignancy to the scene which managed to elude the vigilance of the contemporary critics.

(L) Sidney Nolan, “Urang Creek”, 1947, whereabouts unknown: (R) The wreck of the SS Essex at the mouth of Urang Creek

NOTE. Since this article was posted in Jan 2014, Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan’s book Modern Love:The Lives of John & Sunday Reed has been published and includes a photo of a naked Sunday beachcombing on Green Island in 1946.23 It is reasonable to assume Nolan would have seen this photo, which may have been tucked away in his visual memory and a year later surfaced to influence the imagery seen in Urang Creek.

This new Mrs Fraser painting supports the thesis that Nolan did not create his iconic Mrs Fraser image, seen below, with malice aforethought.

The crouching crawling image of Mrs Fraser is simply his response to the accounts he had read of this Scottish woman’s travails on the island of her name, her hardships and deprivations as she collected roots and sticks. This is the Eliza Fraser of which he had read – the Eliza who went naked on hands and knees in the swamp – and in his well known image, her hair hangs low and covers her face from the prying eye of two centuries of voyeuristic scrutiny. It is an image inspired by sympathy for her plight, not by a transplanted animus.

Similarly in this new Urang Creek painting. Nolan places the Eliza of his ken, lost in a gentle moment of his imagining, in the space he knew at Urang Creek. She sits pensive, back to the water, pondering the beached boat that caused it all. What matter the real Eliza never visited the island’s western shore.

Sidney Nolan, Fraser Island painting 1947, probably “Urang Creek”, whereabouts unknown

The whereabouts of the work is unknown. Jinx Nolan does not recall it.24 Neither does Damian Smith who was archivist for the estate of Sidney Nolan and lived at the Rodd between 1996 and 1999. It reminds him of a group of transfer prints by Nolan with images from life drawings of a woman with hair covering her face. From the late 1940s, these works are done with pale green ink, not red or blue as used in the early Kelly mono prints.25

Platypus Bay

Sidney Nolan, “Platypus Bay”, Oct 47, Queensland Art Gallery

Before the days of widespread air-conditioning the people of southern Queensland needed little warning that summer was on its way. Around October, even when one was sedentary, sweat began to bead on forehead, drip from wrist and trickle down cleavage. “Might be a storm this afternoon” was a common prediction, and as weather warnings go, these folkloric forecasts were more accurate than most.

The storm cells which wreak havoc in the south-east corner of Queensland form near the border with New South Wales above coastal ranges that push the humid air higher and higher. The storm clouds thus formed can reach heights of 20 kilometres and are breathtaking in their lightning-charged beauty as they work their way north and head out to sea, a low flat line defines the rain, and all is topped by massive cumulonimbus cloudballs of strobing gold and yellow. Most spectacular are those with sufficient height and updraft for large hail stones to form. These “big bombies” with lots of hail aboard are really something to behold as the ice brings on their distinctive heavy greenish hue. The cry “There’s some hail in this one” has seen many a gardener racing to cover the tomatoes.

Hail storm over Brisbane

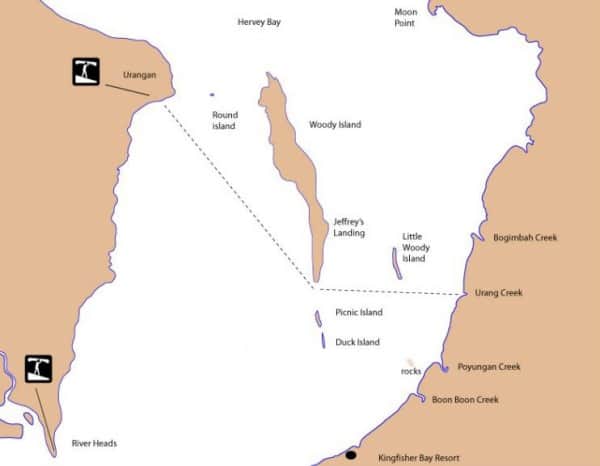

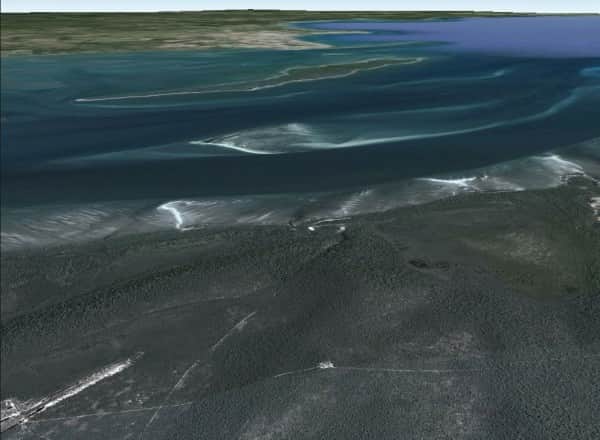

Nolan paints just such a storm cell in Platypus Bay, adding to nature’s palette certainly, but finding the genesis for this evocative work in her spectacular display. One of his most realistic works, its topographical features are readily identified as we look out from a high point on the island, over its west coast to the mainland beyond, with the distinctive forms of Woody and Little Woody Islands afloat in the bay. But the title sits strangely at odds with this realism – for the painting is not a representation of Platypus Bay, which in reality is the large arching sweep of western shoreline on Fraser running from Moon Point to Sandy Cape.

Google Satellite image showing Fraser Island

Nolan’s positioning of the two islands, the larger Woody beyond Little Woody, and their relative lengths, suggests the view point is in the hills above Urang Creek. In the satellite image below, the mouth of Urang Creek appears on the western shore of Fraser directly east of Little Woody Island. The Urang Creek log dump is the lowermost of two side by side white dots on the coastline. The creek runs south-east between and generally parallel with two low ranges and drains a swampy area where the remains of an old airstrip at the Bogimbah Mission Station is still discernible as a white scar on the satellite image.

Google Satellite image showing Woody and Little Woody Islands in Hervey Bay opposite Urang Creek

I first saw the Platypus Bay image in the little catalogue for the 1989 exhibition Nolan’s Fraser at QAG. The work was simply labelled Landscape and kept company with Lake Wabby, Mrs Fraser, Fraser Island and two 1960s convict works – the four from the Moreton show on display together again after 42 years. No painting called Landscape was listed in the Moreton catalogue and I had always assumed, as suggested by the topography, this work must be the one listed there as Hervey Bay. Hence on seeing the actual painting at the viewing prior to the recent auction, it was surprising to learn that Nolan had inscribed “Platypus Bay, Oct 47” on the work.

Not long after seeing Platypus Bay in the flesh I visited Fraser Island for the first time and searched for the view point. The elevated GoogleEarth image below paints the scene. The left-most of the two white dots in the centre of the image is the Urang Creek log dump; the creek threads its way between the hills and to the left/south of the old air strip; all that remains of the 1920s timber rail track skirts the air strip and heads in a a straight line to the log dump; Little Woody Island appears as no more than a sand bar casting a tidal plume; Woody Island is far more anchored; beyond them the mainland reaches north – the urban patch of Hervey Bay township curling around Urangan Point to Point Vernon beyond. The view point, I had decided, was most likely near the elevated white-ish central clearing on the lower track.26

GoogleEarth image looking over Urang Creek and the Woodies west towards the mainland

Sidney Nolan, “Platypus Bay”, Oct 47, Queensland Art Gallery

Standing on the spot where things should have lined up, it was obvious the view point had to be higher – yet I could get no higher. Indeed my lofty vantage point half way up a disused Telecom tower, whose dish now housed an impressive sea eagle nest, was substantially more elevated a position than Nolan would ever have found. Then the penny dropped. He had of course tilted the plane Kiata-like – a similar observation to that made in the 1989 catalogue.27

An odd thread of connectivity by way of conclusion. Nolan’s first wife Elizabeth remarried and in retirement she and her husband moved to the Wide Bay area. She died some time ago now and her ashes are in the cemetery at Vernon Point, on the mainland beyond Woody Island in the painting and opposite Platypus Bay. Indeed, both QAG Nolans from 1947 have time-forged links to final resting places. Mrs Fraser rests on her wall in the Gallery barely half a kilometre from Bracefell’s final resting place in Brisbane’s earliest burial ground, where today the Grey Street bridge disgorges traffic on the other side of Brisbane River. I like to imagine that on moonlight nights, when the guards aren’t looking, she creeps from her frame, trundles across the bridge and keens by his bones.

INVITEES TO THE OPENING

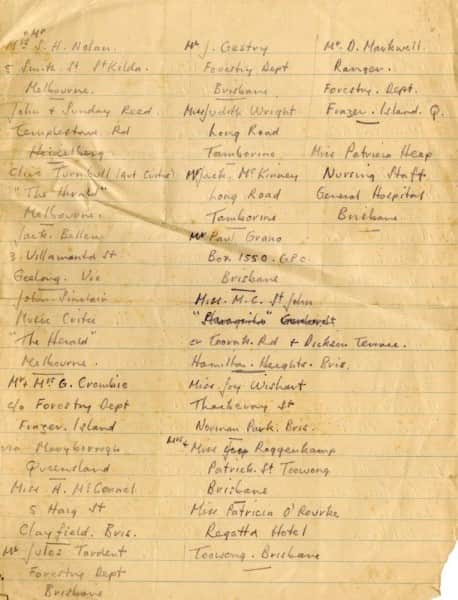

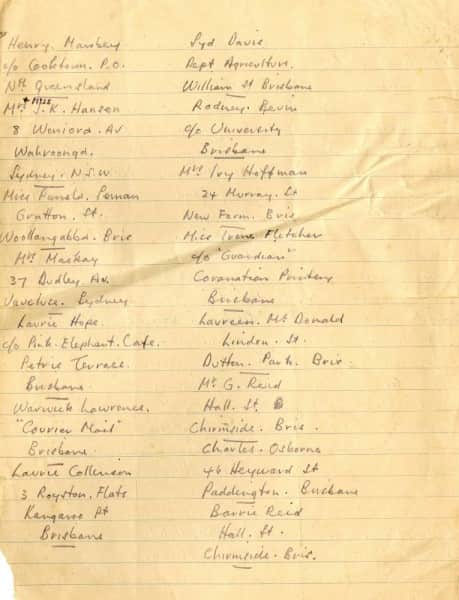

Tucked away in an obscure corner of John Cooper’s papers at the Fryer Library, University of Queensland, I found a list of invitees to the exhibition written in Nolan’s distinctive hand.28 The list provides an interesting insight into a number of facets of his life at this crucial time barely six months after he had parted with Heide and John and Sunday Reed, and a scant month before he married John’s sister Cynthia. It bears witness to his relationships at the time, to his acquaintances, his priorities and his business acumen.

In Sidney Nolan’s handwriting: first page of invitees to 1948 exhibition of Fraser Island paintings at The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane

In Sidney Nolan’s handwriting: second page of invitees to 1948 exhibition of Fraser Island paintings at The Moreton Galleries, Brisbane

An article entitled Nolan’s List is currently in preparation for posting to this website. The article will look closely at these invitees and their various impacts, whether great or slight, brief or enduring, on Nolan’s life and work – much along the lines of the following discussion of Clive Turnbull, the third person on the list.

Clive Turnbull

Stanley Clive Perry Turnbull (1906-1975), whose Australian Dictionary of Biography entry can be read here, was probably a far more influential figure on the early career of Nolan than is generally recognised – particularly in relation to the first Kelly paintings.

Trained as a journalist, Turnbull was associated with the Melbourne Herald newspaper and Sir Keith Murdoch for most of the 1930s and 40s, and was appointed the Herald art critic in 1942. Beyond journalism, he wrote many books of history, biography, art and art appreciation, and published two collections of poetry.

An avid Kelly enthusiast, in 1942 Turnbull wrote a limited edition monograph on Kelly29 and the following year published Kellyana,30 a bibliography of writings on Kelly covering more than 60 years. It records his view that “the most detailed account of the gang’s doings is to be found in Kenneally’s The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang,” and it is perhaps no coincidence this is the book Nolan credits as being the source of his interest. The early 40s was an active period for Kelly aficionados. As well as the Turnbull offerings, there were at least two re-publications of earlier material and appearances of Douglas Stewart’s Ned Kelly: A Play, first as a verse play winning an ABC radio award, and then as a stage play broadcast on radio in 1942 and staged in Sydney and Melbourne in 1943. The Kelly saga was getting a good airing.

In his Nolan biography Sidney Nolan: Such is Life, Brian Adams recounts how Nolan and Max Harris “often discussed ideas for Angry Penguins and one of their recurring themes was the mystique of Ned Kelly.”31 Along with Nolan’s much vaunted Irish ancestry and grand-parental policing at Beechworth, Turnbull could well have been a catalyst for this Kelly mystique – indeed perhaps a direct catalyst, because as a modernist sympathiser he was well known at Heide.

By May 1946 Turnbull was more personally involved with the Kellys. The earliest of the 27 works in the first series, Ned Kelly at Stringy Bark Creek (soon to be known as Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek) had just been completed when it was exhibited in the South Melbourne Town Hall as part of the City of South Melbourne Arts Festival. It was the first public showing of any of Nolan’s Kellys – all of two years before they were first shown together at Velasquez Gallery in Tye’s Furniture showroom, Melbourne. Whether Turnbull, who was on the Art Committee (along with Betty and Esther Paterson, the artist aunts of Nolan’s first wife Elizabeth),32 had anything to do with the Kelly painting being included is not known. Involved or not, Turnbull voted with his pocket. By the time the painting was illustrated in Turnbull’s popular little booklet Art Here: Buvelot to Nolan,33 a year later, it was in his possession.

Nancy Underhill writes that Art Here “provides a simplistic exploration of the nature of art with a capital A.”34 This is exactly the type of book in which a new young painter would wish to feature, especially when his name bookends the title; and exactly the style of author to choose – one who within such a book, would describe him as “…. a lyrical painter, (who) expresses a poet’s view of the world” and “perhaps …. one of the most significant of contemporary artists.”35

Turnbull was an erudite, well connected journalist with an eye for the new and a penchant to express it in his regular Saturday column in the Herald. It is no surprise that Nolan, aspiring and network-savvy,36 would ask him to write a piece for the Moreton Exhibition catalogue and invite him to the opening.37

ENDNOTES

- An account of the breakup of Nolan’s first marriage, told from his wife’s perspective, appears in Frances Lindsay’s essay Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier in the catalogue Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, 2007, p. 67.

- Barrie Reid, ‘Nolan in Queensland; some biographical notes on the 1947-8 paintings,’ Art and Australia, Vol. 5 No. 2, Sydney, September 1967, p. 447.

- Barrie Reid, ‘Nolan in Queensland’, op. cit., p. 447.

- Nolan discusses leaving Heide in an interview with Michael Heyward in May 1991. Of Sunday Reed’s attitude he said “She could never see the logic of why I left … but I couldn’t see the logic of staying”. See Sidney Nolan, Interview Michael Heyward, 5 April 1991, Papers of Michael Heyward, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, PA 96/159, Box 5. A transcript can be read here.

- On 27 July 1947 Nolan wrote to the Reeds from Queensland saying “I cannot realise it is only a fortnight today since leaving.” Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 2, File 6.

- Michele Anderson, Barjai Miya Studio and young Brisbane artists of the 1940s: Towards a radical practice, Thesis, University of Queensland, July 1987, footnote 114, p. 150-151. See also Judith Wright’s address to the 1975 Fraser Island Environmental Inquiry http://www.fido.org.au/moonbi/backgrounders/35%20FI%20a%20cultural%20monument.pdf.

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, Landscapes and Legends, a retrospective exhibition: 1937-1987, International Cultural Corporation of Australia, 1987, p. 18; Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, 2007, p. 242; Michele Anderson, Barjai Miya Studio and young Brisbane artists of the 1940s: Towards a radical practice, ibid, p. 174; D. Helen Friedemanis (Wilesmith), Contemporary Art Society, Queensland Branch, 1961-1973: A study of the post-war emergence and dissemination of aesthetic modernism in Brisbane, Thesis, University of Queensland, February 1989, p. 13.

- The following identifications are definitive, as advised by Nolan authority Geoffrey Smith (email to the writer, 3 February 2014.) The correct identification in the Moreton Gallery catalogue listing (MGCL) of the four works illustrated immediately below is, from left to right: (1) MGCL No 4 Platypus Bay ; (2) MGCL No 3 Urang Creek; (3) MGCL No 2 Fraser Island; (4) MGCL No 1 Foreshore.

The correct identification of the four works illustrated immediately below is, from left to right: (1) MGCL No 10 Hervey Bay ; (2) MGCL No 9 Swamp; (3) MGCL No 8 Island; (4) MGCL No 7 Indian Head.

The correct identification of the three works illustrated immediately below is, from left to right: (1) MGCL No 5 Beach (detail) ; (2) MGCL No 11 Woongoolbver Creek; (3) MGCL No12 Lake Wabby. The only painting for which I have been unable to locate an image is MGCL No 6 “Maheno”.

The painting known today as Mrs Fraser is now at QAGOMA, and is a slightly modified version of MGCL No 11 Woongoolbver Creek. The painting sold at the Moreton exhibition to Dr Lofkovits was No 9 Swamp, but neither Swamp nor No 3 Urang Creek became Mrs Fraser. Swamp was sold at auction in August 2017 to a private UK buyer. It should be noted that MGCL No 8 Island, now at AGNSW, has long been known and until very recently exhibited under the title Fraser Island, whereas MGCL No 2 Fraser Island was given by Nolan to the Forestry overseer with whom he stayed on the Island, thus accounting for its designation n.f.s in the catalogue. It is now in a private collection in London. MGCL No 4 Platypus Bay, now at QAGOMA, was exhibited at QAG in 1989 as Landscape. MGCL No 12 Lake Wabby is now at Heide Museum of Modern Art. A recent post regarding the auction of Swamp is available on this website. See Auction of significant Nolan painting posted 9 August 2014.

- There may be another. Barrie Reid suggested that Nolan may have given a painting to Norm, a Forestry Commission foreman on Fraser Island. See Barrie Reid, ‘Nolan in Queensland’, ibid., p. 447.

- Exactly which of the 12 works listed in the Moreton catalogue is today’s Mrs Fraser has divided the the opinions of researchers. Jane Clark says it is No 2 Urang Creek (Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, ibid., p. 91); critic Joyce Stirling describes a painting which is certainly Mrs Fraser, but she says it is No 4 The Creek (Telegraph, 17/2/1948); and Barry Pearce says it is No 2 Fraser Island (Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, p. 233.) I formed the view that it was No 3 Urang Creek (David Rainey, Nolan’s Mrs Fraser: Reconstruction and Deconstruction). After Moreton, the painting was next exhibited, by now in its present form, in the 1957 Whitechapel exhibition of Nolan works and the Whitechapel catalogue lists it as having been No 9 Swamp in Moreton. I now believe insufficient emphasis has been given to Whitechapel given that Nolan himself would have provided that information only 9 years after Moreton. Moreover a case can be made suggesting that the newly found Mrs Fraser companion piece is likely No 3 Urang Creek.

- Exercise book containing a ledger dated Jan 1948 to Oct 1948. John Cooper Collection, Fryer Library, University of Queensland, UQFL60, Box 3.

- Courier-Mail, Brisbane, 19 April 1949, p. 2. The other paintings in the art panel were works by Harold Herbert and Arthur Murch. The three works were discussed in a talk from radio station 4BK by Professor C. G. Cooper, Head of the Department of Classics at University of Queensland, scheduled for 20 April 1949 but actually broadcast on 24 April 1949. No recording was made, and at the time of writing I am endeavouring to locate photos of the Courier-Mail art panels and also establish whether Professor Cooper may have made notes for his broadcast.

- No record of the sale appears in the Moreton Galleries ledger, ibid.

- Assuming that the work we now know as Mrs Fraser was actually the work called Swamp in the Moreton exhibition, whether Nolan re-acquired Swamp directly from Leopold Lofkovits is uncertain. Dr Lofkovits died 10 October 1952 and willed his personal effects to his niece who lived in New York. Whether he still owned Swamp at his death is not known because the Inventory listing his effects is far from detailed. (Queensland State Archive, Item ID747117, Will file no. 578/1953.) One thing is clear – the work we now know as Mrs Fraser belonged to Nolan when it hung in London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 1957. As for Fraser Island, Jane Clark reports its circular provenance back from Judith Wright to Nolan via, inter alia, Charles Osborne and Bryan Robertson. (Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, Landscapes and Legends, ibid, p. 91.) In her Judith Wright biography, Veronica Brady notes that when Jack and Judith’s daughter Meredith “wanted a pony … they sold a painting they had bought at Nolan’s first exhibition in Brisbane … It hung on Meredith’s wall, but she did not like it, finding it frightening, so the sale was no sacrifice for her.” (Veronica Brady, South of my days: a biography of Judith Wright, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1998, p. 153.) Judith Wright mentions the sale in a 1960 letter to Barbara Blackman: “Your Robertson (?) friend with the Whitechapel Galleries didn’t get here in the end … but he did buy the Nolan picture … This was a break for us because Brian (Johnstone) put it up for auction at one stage and the only bid was five pounds, which would never have paid for a saddle and scarcely even a bridle, but in the end we got 40 guineas for it …” (Judith Wright, letter to Barbara Blackman, 10 May 1960, Portrait of a Friendship, ed. Bryony Cosgrove, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2007, p. 72.

- See http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/21379/lot/41/.

- Sidney Nolan, two photographs of Fraser Island paintings, 1947, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, ibid., Box 16, File 1.

- David Rainey, Nolan’s “Mrs Fraser”: Reconstruction and Deconstruction.

- John Cooper Collection, ibid., Box 37, No 60/P/54-55.

- At the time of Nolan’s 1987 retrospective, Jane Clark noted that Platypus Bay and Hervey Bay were in private hands. (Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan, ibid., last footnote on p. 91.) She recently advised that she thought both were in Nolan’s personal possession at the time (email to the author, 10 November 2013.) Perhaps then Hervey Bay is still at The Rodd.

- Her rescue by the convict – a matter of some dispute – was not on Fraser Island itself, but much further south on the mainland at Figtree Point on the shores of Lake Cootharaba.

- Barrie Reid relates ‘There was no jetty at Fraser …. That night the barge lay off the coast and on the early-morning tide we went up a small creek,’ Art and Australia, Vol. 5 No. 2, op. cit., p. 447.

- Notes from article on the wreck of the S.S. Essex at the mouth of Urang Creek: see online magazine “Upstream Paddle Magazine” Issue No 4, Summer 2007, page 11, http://www.upstreampaddle.com/media/Essex%20wreck,%20Fraser%20Island.pdf.

- Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Modern Love:The Lives of John & Sunday Reed, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2015, p. 185.

- Jinx Nolan, email to the author, 2 December 2013.

- Damian Smith, email to the author, 24 November 2013.

- Andrew Dennis is an experienced ranger on the island, and having seen the Platypus Bay painting is positive it is a view from this old Telecom communications site, saying “It’s the only place where you’d get that view and have the islands and sand bars lined up,” and illustrated his point with another GoogleEarth image. Andrew Dennis, email to the author, 27 October, 2013.

- Robyn Bondfield, Nolan’s Fraser catalogue, Queensland Art Gallery, 1989, page 2 (unnumbered).

- This was a lucky find. Having checked the Moreton ledger looking for sale details and idly leafing through some loose pages at the end of the exercise book, I recognised two pages in Nolan’s hand writing. John Cooper Collection, ibid., Box 3.

- Clive Turnbull, Ned Kelly: Being His Own Story of His Life and Crimes, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1942.

- Clive Turnbull, Kellyana, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1943.

- Brian Adams, Sidney Nolan: Such is Life, Hutchinson, Hawthorn, Victoria, 1987, p. 83.

- The exhibition catalogue is arranged in alphabetical order and with some sense of domestic irony, Nolan’s name is sandwiched between Elizabeth’s cousin Barbara Newman and three other Patersons. (The catalogue is held by the Port Phillip Library Service, local control call no 270336). Some interesting photographs of the exhibition survive in the Port Phillip Historical Archive: one shows the Kelly painting in situ; in a second Esther Paterson is seen surveying the work, and a third shows a different reaction from school children.

- Clive Turnbull, Art Here: Buvelot to Nolan, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1947.

- Nancy Underhill and Barrett Reid, Ed, Letters of John Reed, Penguin, Melbourne, 2001, p. 82.

- Clive Turnbull, Art Here, ibid., p. 30. Turnbull’s lay assessment of the early Nolan is more perceptive than that of the academic Bernard Smith,who in his study of Australian art since 1788 published two years earlier, mentions Nolan just the once – as one of four in the Australian neo-surrealist group, and apparently unworthy of further comment. (Bernard Smith, Place, Taste and Tradition, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1945, p. 222.

- Turnbull was the first of a number of such writers Nolan would rely on during his career. He attracted strong and lasting support from the likes of Colin MacInnes, Robert Melville and Charles Osborne.

- There was concern that Turnbull’s piece for the catalogue would not arrive in time, and a second default catalogue was prepared with a piece by local artist, writer and poet Laurence Collinson. In the end this was not needed, but it can be seen here complete with “Sydney” and “Frazer” typos.

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

Dave, have just finished reading this article/ treatise. You are an amazing bloke, and so knowledgeable that I wonder where you get it all from. It is a fascinating quest you are on and one in which I wish you all success.

Cheers

Mike