A portrait of Cecily by David Rainey.

It is Melbourne, September 1940. The Swans have just thrashed the Tigers to win their fourth premiership flag, and Australia has been at war for a year – a reality biting across a nation that once again has answered the call. Factory bench and office desk alike collect dust as men and women depart for uncertain fates – some to battlefields in the Middle East, in Europe and in Africa; others to local training camps for conscripted Militia, the ‘chockos’ as they become known, who one day soon will march up a track called Kokoda and into history. In 15 months Pearl Harbour will be attacked, catapulting the United States into the war, thereby to launch not only the chockos up the Owen Stanley ridges where against all odds they will halt the Japanese advance; but also to launch wave upon wave of US soldiers on a largely welcoming Australia where, in the parody of the time, they are ‘over paid, over sexed and over here’.

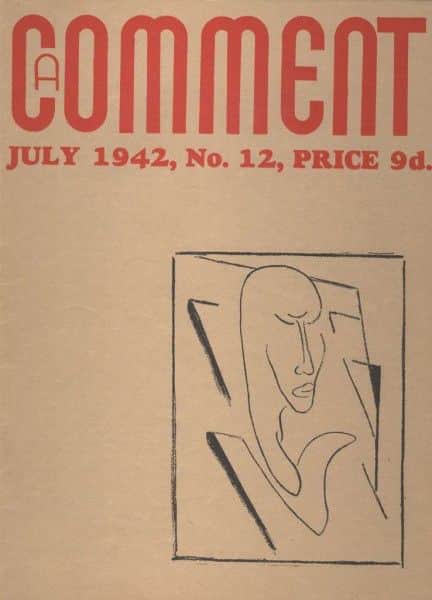

September 1940, and in a flat in suburban Malvern, arm’s length from the theatres of war if not from homefront anguish, Comment is born. It will be one of two little magazines dedicated solely to avant garde art and literature to be published in Melbourne during World War 2.

The better known of the two is Angry Penguins which famously published the hoax poems of Ern Malley. Mainly published and edited by Max Harris and John Reed, a total of nine Angry Penguins appeared between October 1940 and June 1946. The magazine today brings to mind the heady days of an antipodean Bohemia where the Angry Penguins, as the painters and writers who gathered at Heide became known, traveled a road of modernist discovery and experimentation that was wholly captivating for them, enlightening for the more open-minded public if mystifying for most others, and quite enraging for the conservatives – artists, poets and politicians alike.

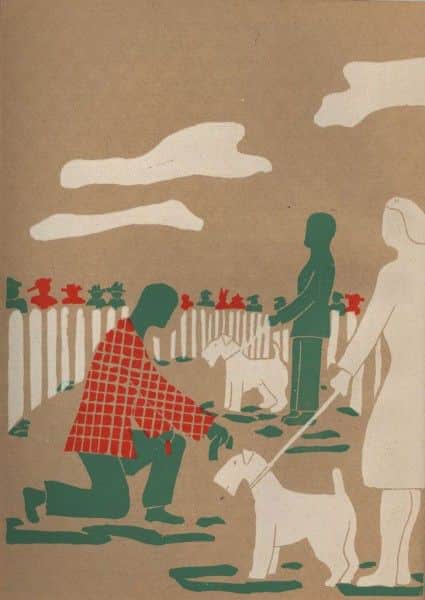

Comment was published by Comment Publications and edited by Cecily Crozier. It first appeared in September 1940 a month before Angry Penguins, and 25 more issues were to follow until declining subscriptions, the fatal flaw with so many little magazines, saw the last issue appear in the winter of 1947 when 150 subscribers could not be found who were prepared to part with the six shillings annual subscription. Mostly designed by Cecily’s cousin Irvine Green, the twenty six issues of Comment are beautiful works of art in their own right. Only one is on ordinary white publishing paper, wartime austerity seeing to that, but rationing restrictions were overcome by using brown wrapping paper which lends the small slim volumes with their tipped in photos and artworks, and their strikingly coloured linocut designs, a charm that makes them unique amongst World War 2 publications in Australia. Comment delighted in publishing opposite views. In an early editorial Cecily wrote, ‘Comment has great pleasure in publishing two such diverse opinions as Max Harris’ and Alister Kershaw’s articles on Adrian Lawlor’s Arquebus. This is one of Comment’s raison d’etre. If you disagree about anything in Comment please write and say so. We want your opinions.’ Contributors included Max Harris, Adrian Lawlor, Alister Kershaw, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester, Noel Counihan, Muir Holburn, and James Gleeson.

Becoming fascinated by the contents of Comment, I wondered even more what was the story behind the publication. Who was Cecily Crozier, what was her background, and how did the magazine commence? What little there was to be found to answer these questions seemed only to whet further both appetite and curiosity. Virtually all references to Cecily ceased with the demise of Comment, and I became all the more intrigued to learn about the magazine, and more about her; particularly what had happened since 1947 when she seemed to completely disappear from the literary map. Then I came across Alister Kershaw’s strangely evocative little memoir HeyDays: memories and glimpses of Melbourne’s Bohemia 1937-1947. 1 HeyDays carries an interesting account of Cecily penned years later by Kershaw (whose poems she published in Comment)looking back 50 years to when as a young twenty year old, who according to Cecily ‘was far too handsome for any girl’s good’,2 he was fascinated by her. In HeyDays Kershaw reports ‘she simply withdrew from the literary world, such as it was, and applied herself to the breeding of dachshunds.’3 Here indeed was a clue. A Google search for ‘cecily crozier + dachshund’ revealed that a Cecily Crozier was a life member of the Dachshund Club of Victoria, and a phone call to its president led to a contact phone number in Adelaide!

Interleaved in my copy of Comment 21 was a small note Cecily had written to a subscriber in October 1944. In indelible pencil, her bold distinctive hand succintly says ‘Your sub was due No 18.’ My first contact with Cecily was for her 93rd birthday when I returned this 60 year old reminder together with three 1940s florins for the subscription and this note. ‘Dear Miss Crozier, a kind man has most generously agreed to look after my outstanding sub for Comment, as per the attached reminder note you put in my October 1944 copy. I do regret that it is 60 years late and I sincerely apologise for this careless oversight on my part. Thank you for your patience. PS Sixpence postage is enclosed.’ Fortunately she was delighted, if somewhat bemused. ‘I thought there must be a madman loose’ she said,4 and in the three years before her death in 2007 I visited her several times, we wrote and telephoned and became close friends.

I learned that Cecily was born in Melbourne in 1911. Niece of Frank Crozier, one of Australia’s official war artists in World War 1, her father Harry was a mining engineer and worked overseas for many years. The family lived first in Burma, returned to Melbourne, and then to London when Cecily was about ten. Deciding that London was too damp and cold for her young family (Cecily had two brothers Laurie and Brian, two and five years her junior) after two years her mother Elsa moved to the south of France, first to Nice and then to nearby Grasse where the fragrances of the flowers grown for perfume making did more harm than the London fog to young Brian’s asthma and bronchitis. The family moved thence to Montpellier where Cecily finished her education – first at a convent , where she was sent “for three months to learn French and good manners. After that I went to the Lycee till I was I think fifteen. Then I learned the piano as I promised my mother to practise four hours a day, which I did for three years till we went to England”.5 Then followed some years in London where she worked as an artist’s model at the time of the notorious exhibition of the ‘obscene’ paintings of D H Lawrence, and several years in Alexandria where her fiancée Nico lived6 and where she designed and made clothes before returning with her mother to Australia once the war began. Deciding that Melbourne lacked an avant-garde literary magazine, without further ado and with little experience but much enthusiasm, one evening in 1940 around a kitchen table reading Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal and translating from the French, she and her cousins Sylvia, Eila and Irvine Green decided to publish one. In July 1941 she married Irvine, a photographic artist and writer, soon after he joined up and was posted to RAAF photo reconnaissance. They were soon to separate, but his brilliant design settings and striking woodcuts and linocuts appear throughout all editions of Comment until it finished six years later.

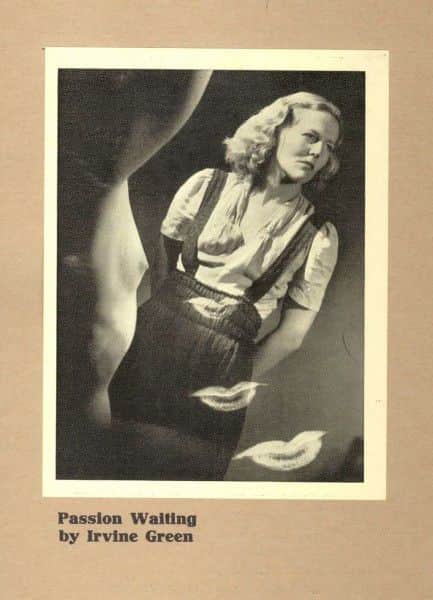

Significantly, Comment also published the work of two Australia-based US soldier poets Karl Shapiro and Harry Roskolenko, and each became Cecily’s lover. Shapiro won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1946 with his V-Letters and he and Cecily had a brief passionate love affair in 1942 when he was stationed in Melbourne for two weeks and she followed him to Sydney for ten short days. His love letters and love poems to her in the months that followed appear as The Place of Love which she published later that year. Many of his poems, writings and translations of Baudelaire appear in the middle years of Comment. Shapiro arranged to meet Cecily, thinking the editor of the little magazine he had seen in a Melbourne bookshop with its striking tipped in avant garde photo of a nude, was a man named Cecil. He visited her Malvern home to discover ‘she’ and not ‘he’ – moreover ‘she’ of the nude photo, the full sized original of which was prominently displayed, along with others, in her home.7

Harry Roskolenko arrived in Australia later in the war and on its completion returned to Melbourne and became more closely involved with Cecily who bore him a daughter in 1947. The last issue of Comment is devoted almost entirely to his poems. In their later autobiographical writings both Shapiro and Roskolenko tantalizingly refer to a Melbourne lady – Shapiro to ‘Bonamy Quorn’ in his Younger Son,8 and Roskolenko to ‘Emily’ in his books Baedecker of a Bachelor and The Terrorized.9 Shapiro’s autobiography is written in the third person, referring to himself as ‘the poet’ and to Comment as Reprise. He writes ‘Almost without kindling, the love affair burst into a conflagration. ….. the poet and Bonamy had fallen in love, in a Little Magazine kind of way, in an avant-garde kind of way, via the upper reaches of the Word, provincial they were both aware, but highly satisfactory under the circumstances, ablaze and no holds barred.’10 In the eponymous chapter Coup de Foudre of her unpublished autobiography Memoirs of an Australian Woman, Cecily tells of her meeting with Shapiro as ‘being struck by lightning.’

The very last words of the last issue of Comment conclude Cecily’s final message to her readers. Telling them rather poignantly that enough is enough, she says ‘Believe me my few faithful readers, I have lived with Comment for seven years and the situation desolates me, but with so many little Magazines the rocks of disaster always loom close. Sincerely. Cecily Crozier. PS Those who have a balance of their subs. can write claiming same or wait with me for a reappearance of Comment.’ The magazine never made that reappearance and Cecily turned her considerable talents and energy towards her love of dogs.

‘Judging the Airedales’, linocut by Irvine Green, Tails Up, ed. Cecily Crozier, Comment Publications

Over the next fifty years Longlo Kennels, her breeding and boarding kennels at Croydon in Melbourne, were to become a leading Dachshund establishment in Australia.11 Divorced from Irvine Green, she married Ernst Heydeman, a strong resourceful Jewish German chemist who had escaped from Germany, spent the war years with the French Foreign Legion in Morocco arriving in Australia about 1950, and was a friend of her music teacher.

I knew Cecily for only the last three of her 96 years. For most of this time she was hale and hearty, read voraciously, played the piano as someone half her age, and when we first met she was still driving her car around the property where she lived. On my visits to Adelaide we made a habit of dining at a little stone cottage restaurant in the Adelaide Hills, and taking a days drive into the country.

Mostly though, we would talk about Comment and its times, and these conversations were fascinating. Typical of them is one I recall concerning two lesser poets Mort Brandish and Rosa Lemmone whom she published. Brandish was, or so the note accompanying his verse led her to believe, an unknown bard from the Isle of Skye;12 Rosa, without even that much pedigree, she nevertheless considered good enough to be runner-up in the Comment Poetry Competition won by artist/poet James Gleeson.13 I told Cecily of having learned that Mort Brandish was the mythical pre-Malley creation of Adrian Lawlor and Alister Kershaw.14 She too had heard of this and was rather less indignant at having been duped, than disappointed that Alister Kershaw had conspired against her. Kershaw also claimed Rosa Lemmone as his and Lawlor’s, but aware of her time in Alexandria, I suspected that Rosa may well have been Cecily herself and suggested this to her adding that I wondered if the name was her play on rosewater and lemon, ingredients long known to Mediterranean ladies for purposes both culinary and contraceptive. Arching one eyebrow grandly and tilting her head ever so slightly backwards and to the side, she assured me Rosa must have been real, ‘After all, she won second prize in my Poetry competition’.

When I last visited Cecily she was in a Nursing Home. This time our days drive took us to Hahndorf, from where, having overstayed lunch and sundry wheel-chaired perambulations, we eventually arrived back to find ourselves locked out of the home. Gaining entry was not without its difficulties, leading her to express surprise ‘that it was harder to get into this place than out of it!’ Her piano playing was usually not for others, but on this last visit as we moved toward her room, she said she would play for me. In the hall, with an audience of one, she played Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata – beginning to end – with hardly an error, and those few to her great irritation. I wheeled her back to her room, and saying goodbye, said to her – she had asked me to remind her not to criss-cross her legs in the chair as it caused her muscles to cramp – ‘Remember Cecily, don’t cross your legs.’ The eyebrow arched again, the head tilted ever so slightly, and she admonished – or perhaps regaled – me with ‘That David, is not something a gentleman should say to a lady.’

Obviously my more personal account of Cecily tells a small part only of her story and touches only on those facets of her character I saw and experienced. Indeed I perhaps saw the best of her in that my contact took her back more than 60 years to a time of youth and love, a time filled with interest and excitement – her Comment time – which she had all but forgotten. I am sure there was a Cecily I did not experience. We enjoyed each others company and got on very well together, but I suspect she was not a woman to cross. Both Roskolenko and Shapiro mention how her home was decorated with her nude photos – a touch here more of Narcissus than of the shrinking violet; and this was something her family recognised – when I checked with her daughter that it would be appropriate to make contact with her and send the old subscription payment, she said ‘Oh yes, my mother loves to talk about herself.’ She was a firm and resolute person, strong willed, perhaps wilful, held her opinions firmly and was not easily swayed from them, did not suffer fools gladly, and I suspect did not forgive easily or quickly. That said, she told me of things she deeply regretted. One, that she had never again contacted Karl Shapiro after the war ended; ‘he was,’ she said, ‘the love of my life’. Another, that she had treated Irvine Green badly. ‘Irvine was a good man and deserved better.’15

At the time of her death Cecily had two writing projects underway. She had completed several drafts of her autobiographical Memoirs of an Australian Woman and selected chapters will be posted on aCOMMENT – one, The Chinese Gentleman, is now available. Deciding that sixty years was long enough to wait for the reappearance of Comment foreshadowed in her 1947 message, she and I re-established Comment Publications and worked together to re-visit Comment. It was our intention to republish those of her choices from among the many striking covers and original articles which she thought were of special importance and significance. To this end we read through all 26 Comments page by page, and recorded her thoughts and recollections. We intended to publish Cecily’s Choice: A Comment re-visited on the same brown wrapping paper that so distinctively characterised the original Comments, along with her thoughts of today to accompany the reprints and with some words from other writers of yesteryear who are still alive. Cecily’s Choice will still be published by Comment Publications and will include the Foreword she wrote a few months before her death on 26 June 2007.

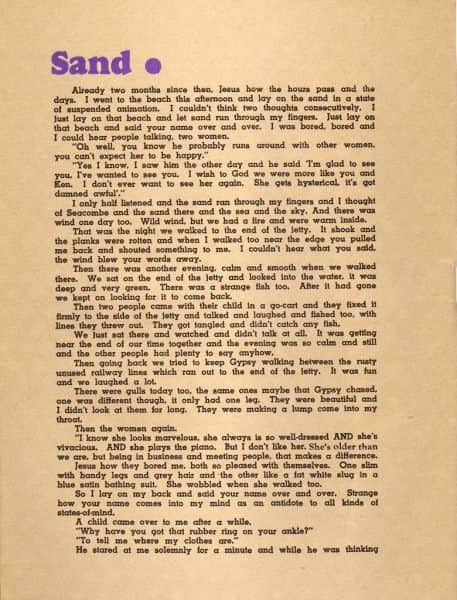

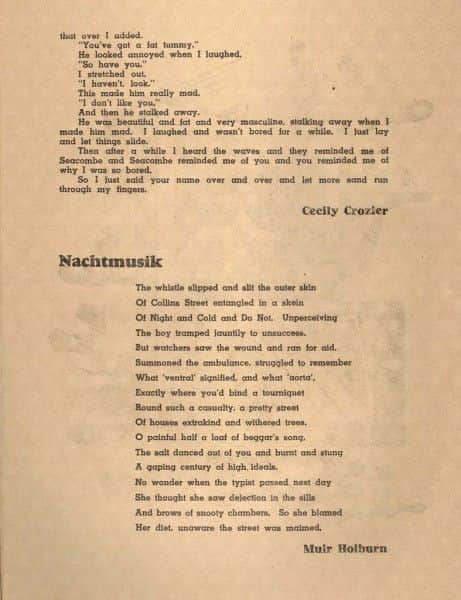

Cecily herself wrote few pieces for Comment. At her funeral two of these were read. She published Sand in Comment 18 in January 1944 and in it she reflects on her final days with Karl Shapiro when they stayed briefly at Seacombe near Sale at the end of their short time together in 1942.

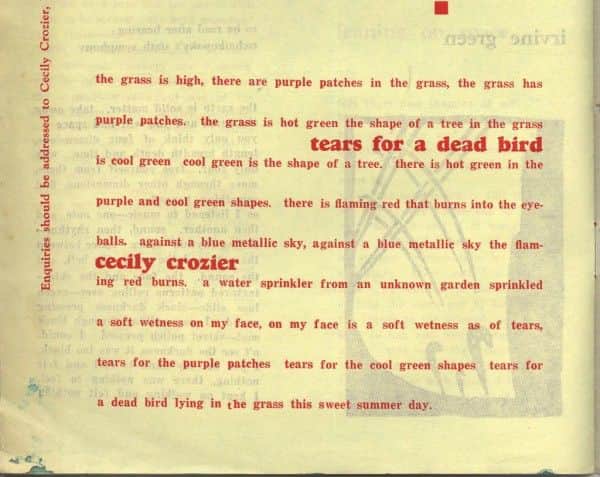

The other is tears for a dead bird published in Comment 3 dated 1940-41. Let this piece be Cecily’s epitaph.

- Alister Kershaw, HeyDays: memories and glimpses of Melbourne’s Bohemia 1937-1947, Imprint, Sydney, 1991, pp 18-26.

- Cecily Crozier, conversation with author, 2006.

- Alister Kershaw, HeyDays: memories and glimpses of Melbourne’s Bohemia 1937-1947, op. cit., p 26 .

- Cecily Crozier, conversation with author, 2004.

- Cecily Crozier, letter to author, 2004. The outline of her early years is condensed in part from our conversations, in part from her unpublished autobiography Memoirs of an Australian Woman, and in part from her brother Brian’s autobiography: Brian Crozier, The Other Brian Croziers, The Claridge Press, Brinkworth Wilts., 2002.

- Cecily met Nicolas Stroumzi in Montpelier where he was studying at the university towards his Doctorate of Law. His doctoral thesis La Question Macedonienne: Etude d’histoire diplomatique et de droit public was published by Bosc Freres, M.et L. Riou, Lyon, 1932, and republished after the war as I, Imprimerie ‘Anatoli’, Alexandrie, 1945. Her engagement to Nico failed to last after she moved to Alexandria to be with him, however she stayed on there and as war approached was joined by her mother.

- The photo Passion Waiting appears in Comment 12, Cecily’s favourite edition. The photo, taken by her husband Irvine Green, was the first photograph to be hung as an exhibit by the Contemporary Art Society which agreed with his contention that photography is a contemporary art.

- Karl Shapiro, The Younger Son, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1988, p. 199.

- Harry Roskolenko, Baedecker of a Bachelor, Padell Book Co., New York, 1952, p. 62-78; and The Terrorized, Prentice-Hall Inc,. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.,1967, p. 55-60, 104, 173. In these books Roskolenko tells of his 1947 journey with Albert Tucker to post war Japan where he received news from ‘Emily’ that she was pregnant.

- Karl Shapiro, The Younger Son, op. cit., p. 205-206.

- An interesting account of her years at Longlo can be found in two tributes published in DachChat, the newsletter of the Dachshund Club of Victoria, Melbourne, January 2008, pp. 9-14. See http://www.dcv.org.au/DachChat/Dach_Chat_Jan_08.pdf

- Comment 8, November 1941: ‘Mort Brandish was born at Skye in the Hebrides in 1909, was educated in Switzerland, travelled extensively, and settled in Australia in 1938. Now he is dead; and it is our sad privilege to present to our readers – as it is their privilege to read – the first of his poems to see publication.’

- Comment 11, April 1942: ‘Mr Gleeson is not unknown – quite apart from his adventures as a painter-explorer in the glimmering caves of Surrealism – as a writer of hallucinatory poems. Miss Lemmone is so far, we think, not at all known as a writer. She has our best wishes.’

- Alister Kershaw, ‘Introduction’, I Shall Not Sleep: The Complete Poems (all six) of Mort Brandish, Angrier Penguin Press, Sydney and Paris, undated (c.1994), p. 6. An interesting analysis of the Brandish/Lemmone hoax perpetrated on Cecily is Tom Thompson’s article, ‘A Comment on Mort and Malley’: Southerly, vol. 63 no. 2, p. 96.

- Cecily Crozier, conversation with author, 2007.

2 Comments

Join the conversation and post a comment.

This was great to find… I was lucky enough to meet Cecily in her later years where I worked for her in Woodcroft Adelaide. I helped look after her dog kennels of 38 Dachshounds. These were one of her true loves. I miss hearing her stories of her life so this was lovely to read and bought back some great memories. I would love to hear more if ever you had the time. Regards Ailie

What a lovely tribute and history. In 1966 I bought a long hair dachshund pup from Mrs Crozier of Longlo Kennels in Central Avenue, Croydon South, as a present for my now wife who was living at home with her parents. My future mother-in-law was not amused, to say the least! However Drucilla or more usually Cilla was such a fantastic dog that she quickly won her way into our hearts. She had several litters and produced lovely puppies too. I am sure that Cilla turned out so well because of Mrs Crozier’s influence on her dogs.