‘Am and Tripe coincides with the visit to Adelaide of a major exhibition of Turner paintings from their London home at the Tate Britain. Two Adelaide children enter Turner’s world and there discover new connections between people, places, events and paintings. But beware – some of the discoveries come from the wonderful world of their imagination.

It seems appropriate that this story should center on Adelaide where, 70 years ago this October, Max Harris received a letter in the mail from Ethel Malley – another exercise not entirely of the imagination. Identifying what is real in this story of Turner, and what is not, can be lots of fun because, as Ern Malley intoned in his last poem, “I tell you – These things are real.”

FOREWORD

‘Am and Tripe was written after I heard that Betty Churcher, esteemed former Director of the National Gallery of Australia, was preparing a children’s book for the opening of the Turner Exhibition in Canberra in June 2013. In her book, children in the paintings would step from their canvasses in the wee small hours and tour the exhibition discussing a number of the paintings, including Scarborough, Town and Castle; morning: boys catching crabs and one of the show’s centrepieces, Disaster at Sea. I was prompted to read about the wreck of the Amphitrite and discovered that the name of one of the convicts who perished, along with her three children, was Louisa Turner.

This led me to further researching, imagining and writing – all of which has culminated in ‘Am and Tripe, which centers on these two paintings and was published online on 3 April 2013 coinciding with the latter part of the Turner Exhibition in Adelaide before it moves on to Canberra. Such coinciding is appropriate because the initial spark for the exhibition came in June 2010 when then Premier of South Australia, Mike Rann, a Kentish man by birth with a passion for Turner’s work, met with Tate Director Nicholas Serota. Indeed, the present exhibition follows 63 years after Australia’s first Turner exhibition from the Tate, also initiated in South Australia, opened its doors in Adelaide.

A few days after ‘Am and Tripe went online, it was suggested that online publication in advance of Betty Churcher’s book might give the impression that the idea of linking children of today with Turner’s Scarborough and Amphitrite paintings was not hers – which it certainly was. Her book and this online publication, even if quite different, will have in common the involvement of children with these two Turner paintings. The initial idea of such linking was certainly not mine – my originality began with the nature of the link. This Foreword has been added to make all this abundantly clear.

The Turner Exhibition in Canberra opens 1 June 2013 and is likely, I suspect, to entice half a million visitors and break the blockbuster record at NGA. Deservedly so – it is a marvellous show.

Tim Turner was bored. Not just bored, but really B-O-R-E-D bored. Year 7 was almost finished, the football was finished, the cricket hadn’t started, and his dad was always on at him about something. His two best friends had left for good during the year. Why didn’t he have their luck he thought, and get to live in big exciting places like Sydney and Melbourne rather than tiny Adelaide.

Things were not looking good, and little Lucy next door was getting to be a real pain. She’d been OK until a few years ago when she stopped being fun and started getting nerdy, and now she was full of herself and letting him know all about her latest crazy ideas. In fact Lucy’s crazy ideas were never ending, for she was quite inquisitive and had the most vivid imagination. But as far as Tim was concerned she was becoming more and more a nuisance and no longer the little kid he’d played with for years. Even worse, two years younger, she was now as tall as him.

The final straw was when his teacher told them they would all have a special assignment for the holidays: to find out something interesting about World War 1 because they would be studying it next year. Just how mean was that – homework over Christmas! So when his dad broke the breakfast gloom one morning with “What’s up Timmo?”, Tim let him know just how he felt about this latest and greatest imposition. “Well,” his dad said, “why don’t you take a look in your great great grandfather’s diary. He was in the British Navy around then.”

Lucy knew all about Tim’s glum thoughts for she was well within his circle of complaining. Each an only child of sole parents, they got on surprisingly well given that she was quite bookish – perhaps ‘netish’ or ‘webish’ would be a better word – whereas he was just the opposite, sports-mad and book-shy.

Just why his dad’s idea about the diary appealed to Tim is difficult to say. It wasn’t so much that it did appeal – just that having to read books about the war seemed much worse. He was even thinking he could ask Lucy to Google it; she spent her whole life Googling things, or so it seemed if the constant stream of nerdy things she kept on telling him was any guide.

So Tim agreed with the suggestion and later that day his dad appeared with an old oilskin wrapped bundle and the greeting “What seas did you see, Tim Cat, Tim Cat.” Tim just shook his head – his dad was seriously weird at times – “and make sure you look after it.” Tim folded back the creased and cracked wrapping that had a smell like …. he didn’t know what. It was like nothing he’d ever smelt before, not nasty or unpleasant, but old and musty and somehow special. The smell of excitement.

With the wrapping gone, on the book cover Tim read SEA JOURNAL – DOUGLAS DUKE TURNER – SURGEON. He slowly turned the yellowing pages and entered the Wonderful World of the Imagination for the first time this long hot summer. It would not be his last visit to the WWI. Throughout the heatwave summer, he and Lucy (who had just drifted in with “What’s that Tim?”) would experience fevers of discovery and imagination.

The first entry in the old sea journal was dated Thursday 10 November 1904. Tim read it aloud: Appointed Surgeon on 23 May and at last here I am. Finally “onboard” HMS Pembroke, but Pembroke doesn’t go to sea – rather it’s a Naval Training Barracks at Chatham and far up River Medway. Still, here it was Drake and Nelson learnt seamanship, so not a bad place to begin! He wondered who Drake and Nelson were but dare not ask Lucy [who, you might have guessed, actually knew all about Sir Francis Drake and his game of lawn bowls, and about Lord Nelson on the Victory at Trafalgar.]

The sea journal kept them busy for hours. Following Pembroke his grandad was on HMS Kent for two years on the China Station, then several more postings before the war began. During the war he served on HMS Sappho and HMS Devonshire. Their imaginations were particularly captured by a three month period from mid-November 1907 when he returned from the China Station to the Home Fleet aboard HMS Amphitrite.

The Amphitrite was launched in 1898 and after several years initial service, had been laid up at Chatham for two years when recommissioned for the Home Fleet in February 1907. That same year she ferried a new crew out to the Kent and early in 1908 returned with the men replaced.

Surgeon Douglas Turner warmed to the Amphitrite as these two entries in his journal show.

Tuesday 21 January 1908. We finally weighed anchor at 6.00 after 2 days on board Amphitrite. Although officially attached to her since she arrived in mid November, I only needed to embark a few days ago once orders finally were given. She seems a good sort and has a nice feel to her. She’s popular with the crew and they call her ‘Am and Tripe. We put in at Kowloon, Singapore, Ceylon, Perim and then the Nore. Should be home in 4 weeks.

Saturday 8 February 1908. Bunkering at Perim Island and taking on 1200 tons. Have been here 2 days and we leave tomorrow at first light. They say we’re the largest ship to enter the harbour! Nothing has changed here in 2 years and I’m sure it hasn’t rained in all that time. The Perim Hotel is still no match for the Royal Marine at Chatham! Looking forward to seeing the Mediterranean again and it will be comfortable in the good old ‘Am and Tripe – she grows on you, even if she exaggerates all weaknesses of the old Powerfuls. Penny pinching! At least we’re not at war beneath her thin 4 inch deck. We should be home about 17th.

As indeed they were and he joined HMS Cochrane at Chatham the next day.

Meanwhile, Lucy had raced away saying she was going home to Google something, and Tim was telling his dad what they’d found, rattling off the names of all the ships. As we will learn, Tim has the most marvellous memory. Without really trying he can recall all sorts of things: events, facts, names, even images! But his dad didn’t seem very impressed. He just smiled his quirky smile and said, “No SS Kidwelly eh. Never mind. I like the sound of the Sappho. No I-love-you-Rosie-Probert tattoos on that ship, Timmo me lad!” What can you do with a dad like that Tim was wondered just as Lucy burst in more excited than usual – even for her. “Look Tim” she shouted, “your granddad’s ship the ‘Am and Tripe. I googled AMPHITRITE and found this.”

HMS Amphitrite

His dad too looked at the photo and they told him what the grandfather had written about the crew’s nickname for the ship. That started up his dad again. “ ‘Am and tripe, Amphitrite; Cockney rhyming slang eh.” Then he talked for too long about Pearly Kings, and how Cockneys were Londoners born in earshot of the great Bow bell, and how they made up nick names that rhymed with the real name of things.

Tim and Lucy found Cockney rhyming slang quite a bit of fun – his dad told them some he knew: Noah’s Ark for shark, Trouble and Strife for wife – but Eau de Cologne for phone, what was that? They thought too it was interesting that tripe was not only the name for the stomach lining of sheep – “Yuk! fancy eating that” – but also a word for a story that was not quite true. This meaning of tripe gave Tim an idea for the school holiday assignment about WW1.

Taking a leaf from Lucy’s book, he was looking up HMS Sappho on Google when he discovered that another ship with a similar name, HMS Sapphire, had landed troops at Gallipoli on Anzac Day. Surely he thought, his granddad must have been on the Sapphire not the Sappho. In the glare of his imagination he could clearly see the WWI diary entry for Monday 26 April 1915.

Writing this mid morning as we await return of the Plymouth Royal Marines. They met severe opposition on the cliff tops, our covering fire of little assistance and after heavy fighting were forced to re-embark. Many wounded. Suspect I will get little sleep over the next few days.

Saturday at Port Mudros we embarked half battalion King’s Own Scottish Borderers and gear, weighed anchor at 6.00 and proceeded in company with the Amethyst, transports Southland and Braemar Castle and 7 trawlers. Stopped at the rendevous off Cape Tekeh at 1.00 and transhipped troops to trawlers.

Night calm and very clear, a brilliant moon set at 3.00. Trawlers left for shore at 4.30. At 5.00 opened heavy fire on Turkish troops attacking from northward. Wonder how our Australian friends are going at Anzac Cove – we’re just south of them.

But all that was for school next year.

The whole time Tim’s dad was going on about rhyming slang, Lucy was frustrated. She wanted to tell them both about her other Amphitrite discovery when she Googled AMPHITRITE + TURNER. Finally, when his dad paused for breath, she almost yelled “Look at this!”

“There were lots of ships called Amphitrite,” she told them, “and one of them was this convict ship full of female convicts, and it was lost in a storm and they were all drowned, and there were children too, and there was a big fuss, and here’s a famous painting about it.” Scarcely drawing breath she went on, “and guess what; the painter’s name is Turner. And he’s very, very, famous.”

“Disaster at Sea. The Loss of the Amphitrite”, JMW Turner, c. 1835

“And that’s not all,” she was really on a roll, “mum’s told me there’s a Turner exhibition at the Gallery soon, and this will be one of the paintings.” [Her mum was a volunteer guide at the Gallery and right then in the middle of studying for her tours.] Then just as quickly as she had arrived she was off again, calling back to them as she disappeared out the door, “Going to find out more about that shipwreck. Keep the picture. I’ve got one. See you tomorrow.” But it wasn’t tomorrow. Lucy was back in a few hours, all lit up like a Christmas tree with excitement and information. Her eyes though were watery and Tim thought she’d been crying.

She had Googled some more and found lots of information about the wreck of the Amphitrite. It was lost in a huge storm in the summer of 1833 when blown across the English Channel onto a sandbar off Boulogne on the French coast. Lucy showed Tim a printout of a letter written from France the day after the disaster. Together, they silently read passages written in the language of that day, Sunday 1 September 1833.

The vessel was about three miles to the east from Boulogne harbor on Saturday at noon, when they made land.—The captain set the topsail and main-foresail in hopes of keeping her off shore.

From three o’clock she was in sight of Boulogne, and certainly the sea was most heavy and the wind extremely strong; ….. the captain ordered the anchor to be let go, in hopes of swinging round with the tide.

….. a brave French sailor, named Pierre Henin, ….. said that he was resolved to go alone, and to reach the vessel, in order to tell the captain that he had not a moment to lose, but must, as it was low water, send all his crew and passengers on shore.

As soon as she had struck, however, a pilot-boat, ….. was dispatched, and by a little after five came under her bows. The captain of the vessel refused to avail himself of the assistance ….. The crew could then have got on shore, and all the unfortunate women and children.

When the French boat had gone, the surgeon sent for Owen, one of the crew, and ordered him to get out the long boat. This was about half past five. The surgeon discussed the matter with his wife and with the captain. They were afraid of allowing the prisoners to go on shore. The wife of the surgeon is said to have proposed to leave the convicts there, and to go on shore without them.

…. it was now nearly six o’clock. At that time Henin ….. swam naked for about three quarters of an hour or an hour, and arrived at the vessel at a little after seven. On reaching the right side of the vessel, he hailed the crew, and said, “Give me a line to conduct you on land, or you are lost, as the sea is coming in.” ….. The captain and surgeon would not. …..

The female convicts, who were battened down under the hatches, on the vessel’s running aground, broke away the half deck hatch, and frantic, rushed on deck. Of course they entreated the captain and surgeon to let them go on shore in the long-boat, but they were not listened to, as the captain and surgeon did not feel authorized to liberate prisoners committed to their care.

At seven o’clock the flood tide began. The crew seeing that there were no hopes, clung to the rigging. The poor 108 women and 12 children remained on deck, uttering the most piteous cries. The vessel was about three quarters of a mile English from the shore, and no more. Owen, one of the three men saved, thinks that the women remained on deck in this state about an hour and a half.

….. (One of the survivors) saw a man waving his hat on the beach, and remarked to the captain that a gentleman was waving to them to come on shore. The captain turned away and made no answer.—At that moment the women all disappeared, the ship broke in two.

Detail from “Disaster at Sea – The loss of the AMPHITRITE”, JMW Turner

….. as soon as the corpses were picked up they were brought to the rooms ….. I never saw so many fine and beautiful bodies in my life. Some of the women were the most perfectly made; …..

More than 60 have been found; they will be buried to-morrow. But alas! after all our efforts, only three lives have been saved out of 136.

They finished reading and looked at each other in disbelief – but this was real! A lot more real, Tim thought to himself, than killing all the baddies in a computer game.

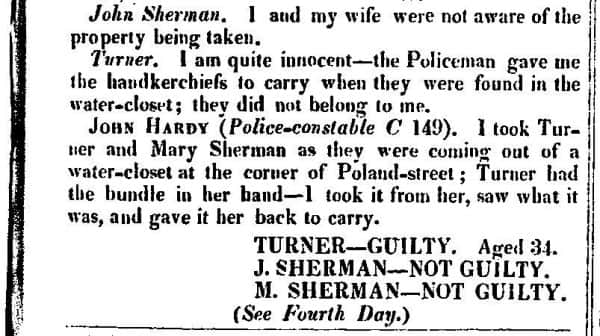

Suddenly Lucy made it all seem even more real when she whispered to Tim that one of the women’s names was Louisa Turner. “She had her nine year old son with her, and a six year old daughter, and a baby. They must have all just drowned.” Tim could feel a most unmanly lump forming in his throat. It made speaking difficult, so he said nothing as Lucy told him about Louisa.

“She was only 34,” Lucy was saying, “that’s how old mum is. There were three of them supposed to have pinched 4 handkerchiefs worth 16 shillings – that’s only $1.60. The other two got off, but she didn’t.” Tim was wondering how she knew so much, but Lucy was just starting. “I don’t think she did it, and she said a policeman gave them to her, and you know what she said?” she asked Tim, “she said ‘I am quite innocent – the policeman gave me the handkerchiefs to carry when they were found in the water-closet; they did not belong to me.’ But it made no difference.”

When Tim said he thought Lucy was making it up, she just looked at him and said she reckoned he’d probably never even heard of the Old Bailey. And he hadn’t of course, so she told him it was where lots of the convicts were sentenced in London and that it was in an old song they had on a CD about being bound for Botany Bay – “which is what they called Sydney,” she added just in case he didn’t know that either. “Well,” she went on, “all the Old Bailey records are online, and I looked it up. The handkerchief business was on the first day of lots and lots of trials. Then three days later the three of them were there again, this time for stealing two pieces of silk that a policeman said he found with the hankies in the water closet – mum said that’s what they used to call a toilet.”

Tim was getting quite interested and asked Lucy what Louisa had said about the silk. “Nothing this time. She said nothing, but the other lady said she’d just met Louisa in the street and that Louisa was sick and that they’d gone together to a house to use the toilet. That made no difference either. And they were sentenced to transportation for seven years. And she had three kids. It’s not fair.” Tim agreed. “It’s worse than just not fair.”

Perhaps when much older, they will recall this day reading about Louisa Turner as the first time they sensed injustice.

Over the next few weeks Tim and Lucy became absorbed in the story of the convict ship, and in the story of Joseph Mallord William Turner whose painting had so captured their imagination.

Tim had never really looked at paintings before and he was amazed that something so blurry and indistinct could seem to be so full of meaning – hardly anything looked real; skies didn’t really look like that, the sea didn’t really look like that, you couldn’t see the ship at all, and lots of it – particularly the women – didn’t even look finished. “Yet,” he told Lucy a few days after she’d given him the printout and he’d surprised himself, and certainly his dad, by looking at it intently for hours, “if it was done like you’d taken a photo, it … it would … ,” he was lost for words, “it just wouldn’t be the same. You’re in it, aren’t you? Not just looking at it.”

Lucy’s mum must have been having a coffee with his dad and heard what Tim had said, because she made a point of telling him that Turner would have been pleased to hear what he’d just said. “Because Turner,” she said, “thought indistinctness was his great strength. He sold most of his realistic paintings, but he kept most of the indistinct ones.” Raising an eyebrow in their direction, she continued, “you pair of budding young art lovers might be interested to know it’s an unanswerable mystery why he never finished that painting.” Lucy and Tim looked at each other – was this a challenge?

Meantime though, they were enjoying learning about JMW Turner. They learned that he was born on Sunday 23 April 1775 in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, London and that this made him a Cockney – did he speak rhyming slang they wondered. He was only eight when his younger sister died aged four. His mother, perhaps unable to cope with her grief, became increasingly deranged and in 1800 when Turner was 25 she was committed to the Bedlam mental asylum. He never visited her and she died there four years later.

He went to school in Margate when he was 12 and his earliest drawings were done here. His father, a barber and wig maker, sold them in his shop. His precocious talent was recognised early and he entered the Royal Academy Schools at age 14, his first exhibit there following within a year – an unheard of accomplishment in one so young. Of slight build, he grew to little more than 160cm in height. Tim and Lucy were nearly that already! His friends called him Little Turner.

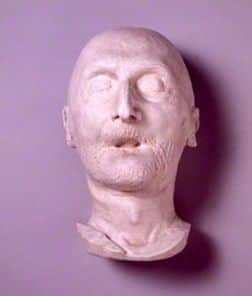

JMW Turner, Self Portrait, 1799, age 24

They read of his travels – touring England, and later the Continent, almost every year until he was 70; and of the many sketchbooks he filled on these travels with drawings for future use. These were now in the Tate and you could see them all on their website. They learned too of his fame, his wealth, and his increasing oddness as he aged; of his love of light; of his fear of death following those of his great friend Walter Fawkes in 1825 and his father four years later; and of his gift to the nation of all works still in his possession at his death, more than 500 oils and upwards of 30,000 works on paper.

He died aged 76 on Friday 19 December 1851, lovingly held in the arms of Mrs Sophia Booth. His head rested on the shoulder of this widow with whom he had lived since 1833 – the year Louisa Turner and her children drowned on the Amphitrite.

One day a few weeks before Christmas, with Tim and Lucy showing no signs of losing interest in this new found (and most welcome the parents thought) passion, Lucy’s mum suggested that Tim and his dad might like to come for dinner and all of them watch a TV programme about Turner in the BBC series “Fake or Fortune.” This was when they first heard in any detail of Mrs Booth or of Margate, a seaside town east of London which Turner loved and where he once went to school.

The question examined in the TV show was whether three paintings given as Turners to the Welsh National Gallery had really been painted by him. Experts had decided some years ago that they weren’t painted by Turner, but the person in the new program thought this had been a mistake. At the end the expert changed his mind – after 40 years he agreed he had been wrong! Mrs Booth comes into this story because the three paintings had been on the walls of her house when Turner died, rather than in his own studio and gallery. Consequently they were not part of his bequest to the nation. Over the years since then Mrs Booth had been poorly thought of within the art establishment. The paintings were first sold by Mrs Booth’s son fourteen years after Turner died. But when it came time to authenticate them for hanging in a national gallery, their chequered past and Mrs Booth’s dubious reputation was all too much for the authorities.

Lucy and Tim came away from the programme determined to find out more about this shadowy lady. They headed for the Internet where they learned that Sophia Caroline Nullt, daughter of Henry and Hannah Nullt, was baptised in Dover on 3 February 1799. When she was 19 she married Henry Pound at Margate – as it happens on the same date as her baptism. She and Henry had two sons: a first named Henry who died at an early age, and Daniel John Pound – he who sold the paintings in 1865. Her husband Henry drowned in 1821 and aged just 22, Sophia was left a widow with two young children. In 1830 she married an older man John Booth and they operated a boarding house on the seafront at Margate. Turner often visited Margate, travelling by boat from London Bridge, and when there he stayed at Mrs Booth’s boarding house.

John Booth died in 1833 and from this year Turner spent more and more time at Margate. Sophia Booth remained at Margate for several years and Turner divided his time between his travels, his home and studio in London, and Mrs Booth’s house. Then in 1846 she and her son Daniel, by now an artist and engraver, moved to London and lived with Turner in his house on the Thames in Chelsea. When Turner died Sophia inherited this house and lived there for some years before selling it and moving away from London. When she died aged almost 80, her body was taken to Margate for burial.

As a result of all this searching, Tim realised that Googling could be very interesting – even if time consuming! It was he, rather than Lucy, who one day in an idle moment Googled TURNER + EXHIBITION + ADVERTISER and found the first newspaper announcement – quite some time ago in October 2011 – that a Turner exhibition was coming to Adelaide from the Tate. But what caught their eyes most when he showed it to Lucy, was the photo of South Australian Gallery director Nick Mitzevich holding one Turner, with another painting Scarborough, Town and Castle, on the wall. This was the Gallery’s own, and worth $20 million!

AGSA Director Nick Mitzevich announces Turner exhibition, October 2011

Lucy asked her mum about it. It indeed was the Gallery’s painting – a gift from the collection of the late Mrs S.M. Crabtree by her children. Its correct title she said, was Scarborough, town and castle; morning: boys catching crabs. Painted in about 1810, it had once been owned by Turner’s friend and patron Walter Fawkes and had somehow found its way to South Australia. “A bit of a coincidence,” Tim suggested, “crabs and crabtree.”

Lucy’s mum showed her how to access the Google Art Project where high resolution detailed images of major works of art in galleries around the world are available online. AGSA had joined the project not long ago, and Scarborough, town and castle was there to be seen. Lucy found it and called Tim over. They were intrigued by the five children in the painting who could be seen in some detail – greater detail, Lucy’s mum said, than were lots of Turner’s figures. Who were they and why did they seem so central to the painting? Was it just the artist composing the structure of the work, or were the children of special significance to Turner?

“Scarborough, town and castle; morning: boys catching crabs”, JMW Turner, about 1810

And so began, for Tim and Lucy, a fascination with Scarborough – or more correctly, with Turner’s apparent liking for the popular Yorkshire seaside town.

Scarborough, they learned, has been a popular seaside resort town in Yorkshire for more than 300 years. The city is dominated by an old stone castle built up on a headland that divides the shoreline into north and south beaches. The old town adjoins the south beach and it was here, beside a small cliff from which a stream of reddish spa water ran, that Turner loved to paint. The Scarborough Spa was built nearby and reading about it, Tim and Lucy wondered whether they might be able to take some virtual steps side by side with Turner.

So they located Scarborough on Google maps, found the street along the South Beach near the Spa, dragged down the little Google streetscape man, and in no time at all there they were – right where he had stood and painted!

Google streetscape of Turner’s viewpoint at Scarborough, 200 years on.

They read too of the old folksong Scarborough Fair, and how a girl is set impossible tasks to accomplish if her sweetheart is to return to her. Tim recognised it from an old CD his dad played sometimes late at night. “Remember me to one who lives there, she once was a true love of mine.” He told Lucy about it and his dad let them play it, but Lucy started singing the first lines over and over until he wished he hadn’t mentioned it. What’s more, she’d sing them saying ‘Tim’ instead of ‘thyme’ until he got sick and tired of hearing “Are you going to Scarborough Fair? Parsley, sage, Rosemary and Tim.”

The Spa attracted many visitors and Scarborough became a famous seaside resort, with its Grand Hotel opening as the largest hotel in Europe. Checking on the Google streetscape photo, they realised that it’s still there today, the big building above the gates going down to the beach – near where the boys in the painting must have been crabbing.

As well as sitting in the spa waters, they learned that some of the visitors would actually bathe in the sea – something most unusual in those days. “But they had to use great big bathing machines”, Lucy told Tim, “and horses would pull them out into the water. Mum said you can see one in the painting.” As well as the Spa, and even before the hotel was built, there were guest houses for visitors – some grand, some not, some with views of beach and castle, some without. Scarborough became so popular that those who could afford it – the Squires, the Baronets and the Sirs, their Ladies and their children – would regularly stay there during summer.

Typical of the families of landed gentry who took to the waters at Scarborough, were the Fawkeses of Farnley Hall and the Grimstons of Neswick.

Walter Fawkes was born Walter Hawkesworth in 1769 and upon his father’s death in 1792 took the surname Fawkes (as his father had done when heir to Francis Hawkes of Farnley Hall) – the name change being a condition of inheritance. At only 23 he was master of the fine Georgian mansion Farnley Hall and its 15,000 acres looking over the River Wharfe near Otley in Yorkshire. Farnley Hall still stands today looking down over its stretch of the Wharfe and is still owned by the family. Its magnificent rooms house a large private collection of his works and are much the same as when painted by Turner.

Looking for a photo of Farnley Hall on the Internet, Tim and Lucy found its website. “Look at this Tim – we can go there and visit. You get a guided tour and tea or coffee and cake for 10 pounds. Wouldn’t that be fun! But there has to be twenty of us.” They were less excited by the photo on the website and thought the painting by Turner of the East Front with the flower garden was much nicer.

The East Front of Farnley Hall, with the Flower Garden and a Sundial, 1815 by JMW Turner

By age 25 Walter Fawkes was married, by 30 his sixth child Amelia had been born, and by 35 he was considering entering parliament – which he did successfully the following year as an anti-slavery candidate, sharing a platform with William Wilberforce. About this time he began collecting paintings by Turner, and by 40 when Turner first visited Farnley, he owned perhaps the largest collection of his works. Fawkes became a great champion, patron and close personal friend of Turner who visited Farnley regularly – almost every year in fact from 1809 until Fawkes’ death in 1825 aged 56. The two of them seemed to be kindred spirits and his friend’s death affected Turner so deeply he did not visit Farnley again.

While today Fawkes is remembered mainly for his Turner connections, it was attributes such as his advocacy of reform, his outspokenness against social injustice and a shared fascination with the landscape that underpinned their friendship. In 1819 in his London home, Fawkes mounted a public exhibition of some of his large collection of watercolours by Turner and wrote the introduction to the catalogue. In it he appears to sum up the basis of their deepening friendship, speaking of the “delight I have experienced, during the greater part of my life, from the exercise of your talent and the pleasure of your society.”

J.M.W. Turner and Walter Fawkes at Farnley Hall, between 1820 and 1824, John R Wildman

By now, the school holidays were drawing to a close and Tim’s dad suggested that Lucy and her mum come across for a meal and that the kids tell the adults how their Turner escapade was getting along. That seemed a nice idea and Lucy’s mum said she’d bring a DVD of the TV series “Simon Schama’s Power of Art”, and if there was time they could watch the Turner episode. They had a great night. Lucy said that she and Tim were going to go to Farnley Hall one day, which made the parents smile, one of them saying that mightn’t be such a bad idea.

But the best part of the night was the Schama documentary. Fawkes of course was mentioned, as was his anti-slavery stance. And for the first time they saw Turner’s Slave Ship painting.

Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing over the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, JMW Turner

A critic of the day may have said Slave Ship was all peagreen insipidity, but Tim’s dad thought better. Looking intently at the ceiling, half empty glass of wine in hand, he started another recitation – a homage, they would one day realise, to both Turner and Dylan Thomas: “Seas barking like seals, Blue seas and green, Seas covered with eels and mermen and whales. Seas green as a bean, Seas gliding with swans, in the seal-barking moon.”

The Amphitrite painting was there in the video too, and its mention turned Lucy’s attention to a namesake, for in her mind’s eye she was forming an unlikely connection between the Amphitrite and the Grimstons of Neswick.

Just why Tim and Lucy became interested in the Grimston family is difficult to know. Most likely it started when Lucy, who was finding out details about Turner’s friend Walter Fawkes, learned that Fawkes married Maria Grimston of Neswick. “The Grimstons of Neswick” had a certain ring to it she thought, Neswick was barely 25 miles from Scarborough, and to give it all a personal touch – Maria’s older sister was named Lucy. Why not find out more? It was fun.

She learned that the girls’ father Robert Grimston was born in 1747, the son of another Robert Grimston whose wife Esther Eyres was the heiress to Neswick, a mediaeval village which came to suffer the fate of many like it – eventual desertion as the number of families decreased from 25 in 1672 to eight by 1764 in the wake of inheritances like Esther’s, the gradual buying out of other freeholders, and the enclosures.

Tim’s dad was pleased to see him showing interest in something other than sport, and it was he who told them about the forced enclosures – the fencing off of what had once been unenclosed common land available for use by all. Tim and Lucy experienced another sense of injustice. “That’s not fair,” Lucy said again. This started up Tim’s dad as if he were on the stage, ” ‘Sweet smiling village, loveliest of the lawn, Thy sports are fled, and all thy charms withdrawn; Amidst thy bowers the tyrant’s hand is seen, and Desolation saddens all thy green.’ Oliver Goldsmith. The Deserted Village. You should read it!”

A combination of all these factors would see the Neswick estates come into the Grimston family. In the 1750s Robert and Esther Grimston built Neswick Hall where their son Robert grew up and in due course inherited the properties. The Hall stood for 200 years, its final use a billet for troops in World War II. Delapidated, it was finally demolished in 1954.

Neswick Hall in early 1900s

Robert Grimston of Neswick and his second wife Elizabeth had five children: Lucy, their first, was born on 20 August 1772, then came Maria who was born in 1774. The two sisters were followed by a son John and two more daughters who were named Elizabeth and Esther for their mother and grandmother.

Robert Grimston and his daughter Lucy, about 1776, Circle of Francis Wheatley

Lucy couldn’t help but think that the two older Grimston sisters must have been very close. She hoped they were – her own little sister Amelia had lived only a few days. She would be eight now, but of course Lucy couldn’t even remember her. She thought how Lucy and Maria had this same age difference, but what really struck her was how similar their lives seemed to be. They both married wealthy landowners who were both Sheriffs of their county – Maria’s husband the Sheriff of Nottingham no less. Tim’s dad said Maria was an ‘n’ off being Maid Marian – he was really hopeless! Both sisters had huge families – they must have been constantly pregnant Lucy said to her mum – and they both died before they were 40, due no doubt her mum said to having all those babies. And “all those babies” was certainly the case – Lucy had ten children in 16 years of marriage, and Maria thirteen in 19 years.

By now Tim was quite hooked on looking up old things (as he put it) on the Internet and it was he who found the genealogy websites that opened a window onto these families. Not their day to day lives of course, but nevertheless Tim and Lucy began to feel they were there with the sisters at all the big events. They imagined celebrating with them in the good times of births and marriages, and mourning with them in the sad times of deaths.

And good times and sad times there were aplenty for Lucy and Maria.

Maria married first – to Walter Fawkes on 28 August 1794. She was just 20 when she became mistress of Farnley Hall. Her first child Walter, son and heir, was born three weeks short of her first wedding anniversary. Young Walter would die just before his 16th birthday – suicide perhaps, his body found floating in the Greater Union canal at Denham where he was at boarding school – in the same week, perhaps on the exact day, 23 July 1811, her last child Lucy Susan was born. Maria herself would die less than three years later on 10 December 1813. She was not quite 40.

Lucy Grimston was 23 when she married Sir Robert Wilmot on 29 March 1796. She became the mistress of Chaddesden Manor in Derbyshire. The old Manor is now gone, but its grounds remain as a park in the Derby suburb which took its name when – reversing the earlier process of land usage – its fields gave way to housing in the 1930s.

Chaddesden Manor

Lucy’s first child was a daughter Lucy-Maria, born – like her sister Maria’s first – barely a year from her wedding. And like Maria, her first born son and heir would not live to inherit his title. Robert-Roberts Wilmot (the Wilmots seemed to like hyphenated first names) was born on 2 July 1799. His young life was cut short when as a Lieutenant in a Regiment of Dragoon Guards he died aged 22 in Brighton on 24 February 1822. Lucy’s last child Edmund was born in October 1809. Like her sister, she would live just 30 months beyond the last birth, dying in May 1812 – again like Maria, just a few months short of her 40th birthday.

The coinciding of her own name with all these Lucys from the past gave our Lucy something more than mere passing interest in the Grimston family. But what set the seal on her quest to really find out more, was her discovery that Maria’s sixth child was named Amelia – the same as the little sister she never knew. Born on 29 June 1799 just three days before her Wilmot cousin Robert-Roberts, Amelia Fawkes became Lucy’s passion. She learned that she married late – aged 29 on 8 December 1828, to Digby Wrangham who was five years younger. She had three children: Walter, named for her father, born exactly nine months after she married; Digby, named for her husband, born in 1831; and Emily born in 1833 – the year the Amphitrite was lost. Amelia would live only a few months more than her mother Maria and her aunt Lucy. She died aged 40 on 11 September 1839.

Here were the bare facts of a life, but what lay behind the facts and between the dates? Lucy became determined to give this Amelia from two centuries ago, a life her own little sister Amelia didn’t manage. Even if it some of it was in her imagination!

As Tim and Lucy learnt more about Turner, about the Fawkes family, and about the Grimston girls Lucy and Maria and their children, they spent hours and hours talking of what had been, and most tantalisingly – what if?

They were beginning to put two and two together in the wonderful world of the imagination. Was it fact or was it fiction in the WWI, and where anyway did one begin and the other end? And they were beginning to believe that they alone knew who the children were in Scarborough, town and castle; that they alone had discovered a reason why Turner did not, indeed could not, complete the Amphitrite painting. They were even beginning to see a vital connection between the two paintings. And they realised the two would soon be coming together again – hanging under the same roof for the first time in 150 years!

It all went something like this.

[The reader will appreciate, of course, that the story didn’t evolve quite as evenly as is written here for the sake of providing a clear narrative. Written too, it must be confessed, in a joint effort with their parents – particularly Tim’s dad, who, alas dear reader, is not overly given to brevity.]

What really happened is that Lucy and Tim played off each other’s ideas and things developed rather more slowly than appears here. The following dialogue is typical.

Tim: “I reckon the key to it all is Margate.”

Lucy: “Why Margate? What’s Margate got to do with it? It’s Scarborough.”

Tim: “Scarborough’s only half the story. Mrs Booth was in Margate. I’ve just read that Ruskin asked the same question.”

Lucy: “What question?”

Tim: “What you just said: ‘Why Margate?’ Listen to this [he reads from a printout] ‘The beautiful bays of north Devon and Cornwall he painted but once and that very imperfectly. The finest sunsets of the Southern Coast series ….. he never touched again, but he repeated Margate I know not how many times.’ That’s Ruskin.”

Lucy: “Well, why do you reckon he painted it so much?”

Tim: “I reckon it had something to do with when he was in Margate at my age. Then he went there again a few more times when he was around 20.”

Lucy: “OK then. We need to find out more about Margate.”

And they did.

Turner’s mother Mary Marshall came from a family of well-to-do London butchers. One of her brothers was a butcher in Brentford, another a fishmonger in Margate. It was to these two uncles the young Turner was despatched from the family home in Covent Garden, “for his health’s sake,” when his mother sank further into the derangement that followed the death of Turner’s younger sister Mary in 1783. Away from London, he attended school and lived with his uncles for about three years in total. He was in Margate for at least a year when aged eleven or twelve in 1786-1787.

His Margate fishmonger uncle lived in Love Lane, then (as it remains now) a short narrow street between Market Place and Hawley Street in the centre of Margate Old Town. Here rough fishermen lived with their families, often in poverty and squalor. Of Love Lane itself, a guide of 1805 had this to say: “A rough lot live here, many of the lowest characters in the town.” Nearby in Love Lane, most likely on the corner with Hawley Street, he attended the school run by Rev Thomas Coleman, initially a follower of John Wesley but of whom Wesley wrote to his Margate followers in 1779: “I have no connection at all with Mr Coleman. I am not satisfied with his behavior.”

Love Lane, Margate, as it is today. Coleman’s School was probably on the corner right.

Young William, or Will as he preferred, made close friends with the Margetson children who lived close by. Their father was a fisherman often at sea, and Tom, who was the same age as Will, and Hannah who was a year younger, spent most of their spare time with him. The three of them roamed around the small town together until Will’s increasing interest in drawing saw them become more a pair than a trio with Tom finding fishing much more interesting than watching Will sketch.

Hannah was exactly the opposite. She trailed along beside Will wherever he went with his paper and box of watercolours. She was right beside him as he painted St John’s Church up on the hill, and it was to her he said it was the best painting he had done so far. Today it is one of his earliest surviving works. As he put aside his brush and told her he was pleased, he would little have realised he had just painted the very graveyard where he would watch his grandson buried nearly 40 years later.

St John’s Church Margate, JMW Turner, about 1786-7; and as it is today.

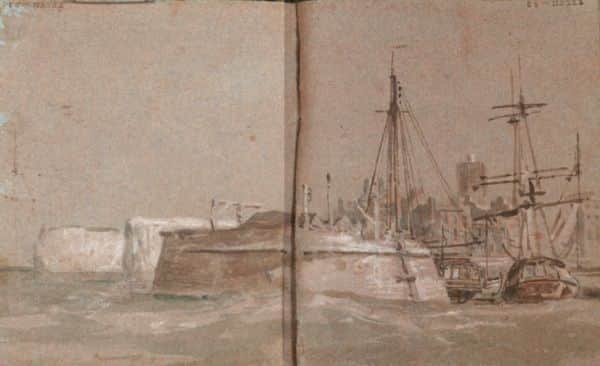

Will and Hannah became inseparable and both were downcast when it was time for him to return to London. The day before his departure they made a point of taking what had become their favourite walk – down to the waterfront, along the harbour shore, and out to the end of the curved pier from where they looked back on the town. Their view took in the twin white cliffs pointing out towards the Channel, then up to the rounded outline of Hooper’s Mill breaking the skyline on Dane Hill, and back across the sweep of the sheltered harbour down to the first row of houses that looked as if they were just waiting to topple into the sea should the wind blow fierce – particularly the three story lodging house near where the jetty began.

She said she would walk out here often, and he told her his uncle promised he could come and stay again – and when he did, he’d paint her this view from the pier as his boat sailed in. Will was as good as his word, but his uncle retired to live in Sunningwell near Oxford and it was there he visited in 1789. He would be eight years away before finally returning to Margate in 1796. As his boat approached the pier he quickly pulled out his sketchbook, almost full from his sketching tour to South Wales the previous year, found a double page and quickly made the drawing he had promised Hannah years before.

Margate Harbour from the Sea, JMW Turner, 1796-7

He was now 21, she 19, and as they let time catch up, filling for each other the years since they were children, the young couple fell hopelessly in love. Hopelessly, in a head-over-heels way, in a losing-all-sense-of-time-and-everything-else way; and hopelessly too, in the sense of being too young, he in particular driven to make his way as the great painter he now felt destined to become. They pledged themselves to each other and he promised to return. And return he did in April 1798 – two years later, and two months too late.

Henry Nullt was a deckhand from Dover on a coastal sailing boat which began to call in at Margate in 1797 on its way to and from the London docks. He noticed the young girl who used to walk along the pier above the harbour to sit alone beneath the light tower, and one day he walked to the end and spoke with her. He was there the next day, and again in a week on his way back to Dover. Hannah was lonely. She had not heard from Will since he left a year ago and she came to welcome the visits of Henry Nullt. When Henry asked her to marry, she told him about Will, but promised to give a definite answer in the new year. Christmas 1797 came and went with no news from Will and when Henry’s boat called in at Margate in February, Hannah relented and she and Henry became engaged. They planned to marry in four months – she would be a June bride.

Will, meantime, had been making his mark. He regularly exhibited oils and watercolours at the Royal Academy and later that year, although young by Academy standards, he intended to compete for election as an Associate. He was developing a reputation and his work was beginning to fetch good prices. In short, he was on his way – a way, he decided, he would share with Hannah.

With this in mind he planned a short sketching tour in Kent over April-May 1798. He based himself at the Parsonage in Foot’s Cray, and from there went on sketching trips with the Revd Robert Nixon and Stephen Rigaud. He continued east on his own, sketching at Aylesford and Canterbury, and then on to Margate – only to be shattered by the news of Hannah’s engagement.

Tearfully she had told Will her story, and with Henry away at sea, on a fine balmy late spring evening in mid April they walked out to the end of the pier together for the last time. As the sun sank, the sky took the colours he would later make famous as his own, and all was mirrored in the dark reflecting waters. The night sky slowly became velvet, and from where they lay in the lee of the light tower they watched a waxing crescent moon sink until it sat on Hooper’s Mill, a forlorn jester’s cap. The sun would rise at 6am and they returned only when its first faint flushes tinged the eastern sky.

Will left Margate that same day, his sketchbook untouched. Six weeks later, on Saturday 2 June, Hannah married Henry Nullt. She was delivered of twin girls towards the end of January 1799 – brought on early as was common with twins, she told Henry. But of course she knew different.

Early in her pregnancy she had managed to get a message to Will telling him she was expecting. In spite of his keen sense of betrayal and disappointment, on receiving Hannah’s news he was determined to visit Margate late in January. This he did – leaving no trace of his visit in either sketchbook or notebook. He contrived a plausible story to explain his presence – an old family friend turned painter and wanting to capture the winter moods of the sea and the white cliffs.

What he found alarmed him greatly. There were two babes not one, the birth had been difficult and Hannah remained very weak and in some danger – indeed Henry insisted on returning to Dover where he had family, but whether Hannah could travel with the tiny twins Louisa and Sophia seemed most doubtful. Of the three, Sophia was the only one thriving – Louisa, the first born, was getting weaker by the day with Hannah barely able to feed one baby let alone two.

It was then Will had an idea he thought might ease the very real burden Hannah faced, and at the same time ease the personal anguish he was feeling. He suggested to Hannah and Henry that he could take Louisa to London and raise her as his own daughter with the help of a recently widowed neighbour with a young family. He would hire a wet nurse for the boat trip back to London. After much soul searching Hannah and Henry saw merit in the suggestion and agreed. Henry would never know that Hannah’s pregnancy had been full term.

None of them could possibly have imagined where their actions would lead, as without delay, Will and the little Louisa departed for London; while Hannah, Henry and Sophia sailed around to Dover where, on 3 February 1799 in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Sophia Caroline Nullt was christened.

From the very start, things did not go well for Louisa in London. Will had been both naive and insensitive to have thought the widowed neighbour would be able to assist with a baby not her own at this time. George and Sarah Danby had lived with their three children close to the Turners in Covent Garden, and counted Will their friend. George was 41, a glee composer and organist; Sarah 33, a singer and actress. George suffered a stroke in 1797 and with timing he would best have avoided, died at the very end of his own benefit concert on Wednesday 16 May 1798, when Turner was away sketching in Kent. Sarah was two months pregnant when widowed and Teresa, her last child with George, was born when Will travelled to Margate to be close by for Hannah’s confinement.

It was to Sarah Danby that Will confided his heartbreak and they consoled each other in their separate sorrows. But their mutual consolations masked the tensions caused by the presence of Louisa in Sarah’s household. These came to a head after Sarah fell pregnant during Christmas celebrations in 1800. She demanded that Louisa be removed from her care, and her tirades were such that Will was pleased to depart in June of 1801 on his annual sketching tour, this time to Scotland via Yorkshire where he would visit Scarborough for the first time.

He stayed at one of the better guest houses, one that usually took families. It had views over the south beach along which he walked at low tide down to the Spa. From here he could look back along the sands up to the old castle at the far end above the harbour. It made him think of Margate, and he sketched the view quickly, roughly – a memory too raw to dwell upon.

Scarborough from the South, JMW Turner, 1801

He was particularly taken by a very large family staying at the same guest house: two families really, just the mothers, both quite young, obviously well-off, and each with swarms of young children – there seemed to be almost a dozen of them! As best he could make out they were sisters who had once lived nearby – he heard Neswick mentioned often – and now married, they were intent on creating for their own children the grand times they had at Scarborough when they were little.

Their happiness contrasted sharply with the sadness he saw in the owners of the guesthouse. A middle aged couple, they had lost child after child; her recent, probably final, pregnancy ending with yet another stillbirth. They were sadly resigned they said, to being childless. His sorrow for their predicament combined with despair at his own domestic situation to suggest a solution to both. He told them little Louisa’s story openly and frankly. Would they like to take her as their own?

Without a moment’s hesitation they said yes. On his return to London in August, Will told Sarah – now eight months pregnant with their daughter Evelina – of his plans. Little Louisa, not yet three, was placed in the care of a trusted friend and taken to her new home in Scarborough. As she was carried away, Will felt the first pangs of a guilt that would remain with him – he had taken his child from her mother and had then given her away. He resolved to make amends for this, at least in his own mind, by being a guardian angel – albiet from afar and incognito.

And so it was that Turner’s daughter Louisa grew up in Scarborough where, every couple of years, she played with Lucy and Maria Grimston’s children – for it was of course Lucy and Maria who Will Turner had seen on his first Scarborough visit in 1801.

By the time she was ten, Louisa was a very happy and contented child, greatly loved by her parents (as she believed them to be) whom she loved deeply in return. She helped about the guest house as was expected, she went to school where she showed much promise – she even went to church on Sundays, although that was far from unusual 200 years ago! Most of all she looked forward to the summer holidays leading up to Michaelmas. The guest house was always full and she was always busy; but that mattered little because at this time, every second or third year, the Fawkes and Wilmot families came to stay for six weeks.

And what times they were!

Louisa was only a few months older than Amelia Fawkes and Robert Wilmot and over the years the three of them became a team. When younger they were chaperoned (if that was really the word) by Amelia’s sister Lucy-Maria who was two years older and so deemed much more responsible. They explored along the beachfront down to their secret place at the end of the beach under the cliff where the reddish-green water trickled across the sands to the sea. In later years they all thought they could remember going together to the Point, as they called it, that first year in 1804.

Lucy-Marie would divide her time between the three younger folk and her cousin Walter who was 18 months older than her, but it was Amelia, Robert and Louisa who spent all their time together. The first thing they would do after arrival, when the trunks were unpacked and they were finally allowed to play, was head out to the Point. Here they would tell their tales of what had been happening in their lives at Scarborough, Farnley and Chaddesden. And they would always go crabbing on the sands at low tide, scooping up the tiny crabs with a hoop net as they had been taught by Tommy Turner, a local fisherman’s son.

These truly were the best of times.

Their fourth summer together was in 1810 and in August that year, Mr Turner the painter first came into their summer holiday lives. Since 1799 when he had left Sophia with Hannah in Margate and then later sent Louisa to her new guest house home in Scarborough, Will had attempted to stay in touch – if not with the children, at least with the adults caring for them. And he had kept in touch after a fashion – sadly, a fashion dictated by the self imposed demands his increasing success with brush and palette brought him.

One thing he had done. In 1808 he first met Walter Fawkes who had been collecting his paintings for some time, and at Fawkes’ invitation he visited Farnley Hall. The two men enjoyed each other’s company, they shared many common interests, and when it became obvious that he knew Mrs Fawkes from the guest house in Scarborough, it seemed natural that Turner confide to his host the true nature of his relationship to Louisa, of whom Fawkes had heard much from his own family.

Fawkes wished to see much more of Turner – not only for the pleasure of his company, but also to be in a position to have an early call on any paintings he particularly liked. He told Turner that a room in Farnley Hall had been set aside for him and was at his disposal whenever and for however long he wished. Moreover, he had arranged with his wife that in those years when they did not go to Scarborough, Louisa should spend the summer holidays with Amelia at Farnley. This suited Turner admirably and from 1810 until Fawkes died in 1825, there was not a year he did not stay there.

Meanwhile his friendship with Sarah Danby waxed and waned as she became older and her own family grew up. Their daughter Evelina, who was now nine, insisted on being called Evelina Turner rather than Danby, and this became an embarrassment for them both. It combined with his emerging fame to make him more and more secretive about Sarah’s existence. Nor was their relationship helped by his reluctance to part company with his Margate memories. When he heard from an old Margate friend that Henry Nullt, Hannah’s husband, had died, he wrote to her, less in sorrow than in the hope, as he put it, that she would come to London and they could all live together as they had once hoped – he and Hannah, with Louisa and Sophia.

Her reply came in July 1809 just before he set out for Farnley Hall from where, he had planned, he would sidetrack to Scarborough and tell Louisa her true story and pave the way (a task demanding some delicacy he realised) for her to eventually leave Scarborough and join them in London where he had just purchased a larger house with this end in mind. Hannah’s reply was brief. She did not want to live in London and she did not want to leave Margate – she intended to remain there with Sophia. It was the second time she had doused his hopes. He pulled out his sketchbook, and impatiently – the page is upside down – he roughly drew a man and woman in apparent confrontation. Scrawling across it “Woman is doubtful love,” he left for Farnley.

Two Figures, JMW Turner, 1809

That year he visited Scarborough only briefly – long enough to see Louisa for the first time in several years. She was now ten, and her foster parents suggested she show him her favourite spot because he was a painter and would like to see it. So she took him down to the Point from where he painted a few watercolours looking across the sands at low tide to the castle, one of them with a boy and his father crabbing while his mother washed clothes in the little pool and hung them on the rocks to dry. Louisa said the boy was Tommy and that his name was Turner too.

“Scarborough”, JMW Turner, 1809

“Scarborough Castle: Boys Crab Fishing”, JMW Turner, 1809

He went to Scarborough again the following year and stayed at the same guesthouse. Although Louisa remained quite ignorant of who he was, she warmed very much to this stranger who was so good with children and she loved watching him sketch. One fine summer day, the five of them, for Lucy-Maria and young Walter came too, took Mr Turner down to the Point. He told them he’d done a sketch here almost ten years before, as well as some last year, but now he would paint a larger watercolour and put them all in as they chased after crabs.

Detail, “Scarborough, town and castle; morning: boys catching crabs”, JMW Turner, about 1810

Looking closely at Scarborough, town and castle; morning: boys catching crabs, it is clear that the figures in the foreground are not all boys and we can easily imagine who all of them are. Kneeling at the back are Lucy-Maria Wilmot who is thirteen, and the young Walter Fawkes with his hand resting on his cousin’s shoulder. He is exactly fifteen – for it is 7 August, his birthday. The other three are all eleven. Robert Wilmot is centre stage with the hoop net, Louisa kneels behind him wearing the striped cap, while Amelia Fawkes looks over her shoulder and away from the older pair. The painting seems to focus on Louisa and begs the question, why does she look sad and pensive?

Maria Fawkes loved Scarborough, town and castle the moment she saw it. It captured the essence of much she held dear, reminding her of her own childhood with her sister Lucy on the Scarborough sands, and showing the bonds being formed between their children. However it took on much deeper meaning and poignancy less than a year later, when young Walter Fawkes’s body was pulled from the canal close to his school outside London. The painting became a memento of their last time together at Scarborough, and for that reason Turner, who was at Farnley when the sad news arrived, gave the painting to Maria.

Turner returned to London in September of that watershed year of 1810, intent on putting his private life into some order. Although he kept it secret – perhaps guarding against what he saw as a distinct possibility that things might not work out – he asked Sarah Danby to live with him. She moved in to his Harley Street house and soon after they shifted together to his new residence in Queen Anne Street West. His caution was well founded, for although another daughter Georgiana was born to them in 1811, life with Sarah was anything but restful and within a few years she had moved out. She remained a presence though throughout his life, because of their daughters Evelina and Georgiana, and because John Danby’s niece Hannah became his housekeeper at the gallery premises.

The next few years were difficult for the Fawkes and Wilmot families. First of all, young Walter Fawkes drowned in the summer of 1811 at almost the same time his mother Maria was giving birth to her last child, a little girl Lucy, named for Maria’s sister who had been in very poor health for some years and who died soon after in May 1812. Maria never really recovered from this twin bereavement and worn by years of childbearing, she too died just before Christmas the following year. In barely two years Amelia had lost her brother, her much loved aunt and her mother; while cousin Lucy-Maria was no different, the same deaths taking her secretly loved cousin, her mother and her aunt.

The best of times were changing.

Meanwhile the pattern of Turner’s Yorkshire interludes continued. He visited Farnley every year and every second year Louisa holidayed there with the Fawkes family. He had hoped to get across to Scarborough for the times they were all there together, but his growing reputation and the resulting calls on his time meant he did not visit Scarborough again until 1818. Both families were there and he travelled with the Fawkeses back to Farnley as before.

Louisa and Amelia were now 19, both quite conscious of their charms, and both secretly in love with Robert Wilmot. He was Amelia’s cousin of course, but that counted for little in those days. Both dared to hope that Robert, now a Dragoon wearing a magnificent uniform astride a prancing bay stallion, might notice them as something more than the little girls with whom he once built sandcastles and played hide and seek. Louisa fancied herself quite fetching with her coquettishly balanced white parasol, while Amelia more demurely relied on a comely white bonnet or a perky sun hat. That same year Turner painted them so attired, first skipping along the beach at Scarborough, and later looking out over Wharfedale from the viewpoint on the south terrace at Farnley Hall.

“Scarborough”, JMW Turner, 1818

“The Wharfe from Farnley Hall”, JMW Turner, 1818

The year of 1818 became something of a watershed in Louisa’s life. The lady she had always thought to be her mother died in the spring, and at Farnley she learned the truth. Indeed, on the very same day he painted the scene at the terrace viewpoint, Mr Turner came across with Sir Walter and sitting down with her on the settee around the tree, told her what had happened all those years ago. The surprise and excitement of learning she had a twin sister Sophia was more than drowned out by the sadness of knowing that the woman she loved as a mother and who had just died was not her mother at all, and that neither was her father the man she had loved as one. More than this – she could not help feeling that she had not been wanted and was abandoned by her real parents.

Her friendship with Amelia – whom she thought of as truly her sister rather than the new found Sophia in Margate – was suffering the strain of their mutual affection for Robert Wilmot. She was sure Amelia would be more the focus of his attention than would she, as well as being more central to the dynastic planning of both families – no matter whether her father was guest house owner or painter. Neither was she looking forward to returning to Scarborough and to the increasingly difficult (and tedious and boring) task of warding off the unwanted advances of Tommy Turner, who was nowadays much interested in exploring with her pursuits far removed from crabbing.

In 1820 her father (she was slowly bringing herself to call Mr Turner her father) came across to Scarborough from his regular stay at Farnley. He brought Amelia with him and the two girls spent hours together talking over the past and looking to the future. They were delighted to find a natural renewal of their sisterly affection when, for the first time, they spoke openly and maturely of their love of Robert and of their hopes for a future with him, if not for one of them – then at least for the other.

Her father (Mr Turner that is) had painted another view of Scarborough from the Point, a dark and sombre outlook this one – with grey skies, beetling crags and an ominous still sea. He said the painting reflected the lack of family in his life and that he wanted to put people where he now found emptiness. He wanted Louisa to come to London with him and then journey on to Margate to meet, for the first time, her twin sister Sophia.

“Scarborough”, JMW Turner, c1820

He explained to Louisa that he had been no more diligent in staying in touch with Sophia than he had with her – if anything he had perhaps been worse, because of the hurt he still felt (unjustifiably Louisa thought) from Hannah’s refusals and his fear that seeing them would re-open wounds he suspected had never really healed. Notwithstanding this, he finally sought out information through his Margate friends. He was dismayed to learn that Hannah had died some years ago, and that Sophia was now married and mother of two small boys Henry and Daniel Pound.

Turner and Louisa eventually went to Margate together in the late spring of 1821. The final coming together of father and daughters after 22 years was not as strained as might have been expected, although this was not due to any filial piety on the part of the girls. Rather it was due to the fact that the travellers arrived in Margate just in time for the funeral of Sophia’s husband Henry who had accidently drowned, and their genuine grief for Sophia and their consolations in her bereavement forged a bond which otherwise may have taken years. The two girls in particular felt very close. They resolved to keep in touch with each other and with their father.

One afternoon before they returned to London, Turner suggested they take a stroll together. He led them, each sister carrying one of Sophia’s children, out to the end of the pier. Sitting in the lee of the light tower and gazing across the harbour to the town, his painter’s eyes betrayed his emotions as he slowly and delicately told them of the evening with their mother in this very spot almost 23 years ago to the day. Tears came to their eyes as he described the waxing moon sitting atop Hooper’s Mill – the mill still there in 1821 up on Dane Hill – although it would soon be pulled down, its sentinal finger to be replaced by the tower of a new Trinity Church until it too came down, victim of enemy aircraft 120 years later.

While travelling back to London on the packet steamer, Turner told Louisa she had two half sisters. Looking forward to meeting them, she was disappointed when Georgiana, now ten, was childishly aloof, while Mrs Danby, by this time increasingly estranged from Turner, showed no more interest in her than she had 20 years earlier when Turner unexpectedly asked her to care for the babe he brought from Margate.

Evelina had married Joseph Dupuis, the British Consul to the African Kingdom of Ashante and was now there with her husband. While staying briefly with her father in London, Louisa read Evelina’s letters to Turner and was fascinated by her descriptions of the slave trade and its horrors. For years she had listened to her father’s discussions with Sir Walter at Farnley and she knew both men were strongly opposed to slavery. Reading Evelina’s letters, one of which mentioned an infamous incident in 1781 when a slaver nearing port threw chained slaves overboard to profit from insurance, Louisa extracted from her father a promise that he would make an abolitionist statement by painting the scene.

From London, Louisa and Turner travelled on to Farnley together, where an estatic Amelia broke the news that she and Robert Wilmot, who had just received his promotion in the Dragoons, were to marry. Broken-hearted herself, even if happy for Amelia, she returned to Scarborough to learn that her foster father had remarried and that her stepmother was her own age. Louisa felt quite alone and unwanted.

A year later in 1822 it truly was the worst of times when Robert Wilmot died, unexpectedly and unexplained, in Brighton. Neither her life, nor Amelia’s, would be the same again. Although not estranged from Amelia, but rather feeling that her own feelings were somehow subordinate to the loftier grief of a fiancée, and with both her fathers preoccupied – the one with a young wife, the other with his brushes and paints – she was bereft. Sir Walter was kind and pressed funds upon her, muttering when she told him she had difficulty talking to her father or asking for his assistance, that “painters should not have wives and daughters.”

Tommy Turner though, still about in Scarborough, while knowing little of the reasons undelying her unhappiness, was not indifferent to her gloom. Indeed he did his utmost to lessen it, and in this achieved a measure of success as Louisa spent increasingly more time with him. The Scarborough fishwives merely nodded their heads knowingly when, decidedly pregnant, Louisa began living with Tommy not long before their child, a little boy Tom, was born in 1824.

They did not marry – it was hardly necessary Louisa thought: her father’s name was Turner, her child’s father’s name was Turner, and certainly there was no property save Tommy’s few fishing nets for the legality if not sanctity of marriage to preserve. However an unwed foster daughter with child was too much for a respectable newly-wed Scarborough guest house owner to acknowledge, as it would most likely prove to be – or so Louisa imagined – for Farnley Hall. In this she would have been wrong, but she gave it no chance, instead writing to Amelia to tell her of little Tom.

The year little Tom was born, Sophia’s first son Henry died. Turner was with Sophia when the little coffin was laid in the graveyard of the same St John’s church he had painted, still a child himself with Hannah at his side, almost 40 years before. Louisa learned of this from Turner when he visited Scarborough from Farnley that same year. It would prove to be his last visit to both places – his great friend Walter Fawkes dying the following year, Turner unable to bring himself to visit Farnley Hall again, and Louisa soon to leave Scarborough for London.

Turner was unaware of what had occurred in Louisa’s life when he visited Scarborough in 1824. Accepting of it all himself, in spite of his best efforts he was unable to effect recociliation between Louisa and her foster father. His first glimpse of Louisa that trip remained a poignant memory for the rest of his life. Searching for her small roomings with Tommy and told she was most likely down on the sands helping with the catch, he wandered down by the Point where he had first painted 23 years ago. He saw her in the distance, forlorn. She stared across at him as she wielded the heavy triangular net used to scoop up cockles, a tightly shawled tiny Tom snuggling in a wicker basket away from the tide. The image was seared on his painter’s eye, to remain there until quickly rendered twelve months later in a small brooding watercolour – his last painting of Scarborough.

“Scarborough”, JMW Turner, 1825

In 1825 Louisa began the last quarter of her life by leaving Tommy, leaving Scarborough and moving to London with little Tom. Her father had suggested it – they would see more of each other and it would be much easier for her and Sophia to spend time together. But when she arrived at his Marylebone gallery, her carry-all on one arm and little Tom on the other, the housekeeper – a woman named Hannah with heavily bandaged face – refused to admit her until Turner’s father arrived mid morning from Twickenham where he lived with his son and did his gardening and cooking. She liked her grandfather, he seemed kind and took her and Tom back to Sandycombe Lodge that evening. It soon became obvious though that a young mother with toddler would not easily share a house with two older men well set in their ways – one 50, the other 75 with only four years to live.

After a week or so she was about to suggest this to her father as they strolled one evening down to the Thames, when he told her he had arranged for her and Tom to live in the Ship and Bladebone, a public house he owned in Wapping and which, having converted it from two side-by-side houses he inherited from his uncle in 1820, he had leased to a Mrs Croset as publican. He had in mind that if the arrangement with Mrs Croset did not improve (as well he thought it should, for she had already drawn unfavourable comment in a report in 1822 to the House of Lords by the Coal and Corn Committee on a petition by coal whippers and basket men), Louisa could make use of her experience at the guest house in Scarborough and manage it. Indeed, he was trying to buy the guest house where they had stayed near the pier in Margate, so that Sophia could do the same. He might even find a husband for them both, and had in mind one John Booth whom he knew as publican of the Star, a public house just around the corner from the Ship and Bladebone.

Louisa’s move from Sandycombe Lodge would prove fateful, for she would soon come face to face with the seamy world of Wapping and Shadwell. An excellent account of the desperate life of the poor there appears in The Maul and the Pear Tree by P. D. James and T. A. Critchley, a modern-day recounting of the 1811 Ratcliffe murders. Until Jack the Ripper, these murders were the quintessence of British horrer crime and occurred only a few hundred yards from where The Ship and Bladebone was sited in the Milk Yard just off New Gravel Lane, which is better known today as Garnet Lane. Even closer was Peartree Court where a young David Bracewell was alleged to have attempted to steal a watch – an attempt successful only in securing for him 14 years transportation to the penal colony of Moreton Bay from where he would escape, and three years after the Amphitrite was lost, meet up with the shipwrecked Eliza Fraser on the island now bearing her name.

The next few years for Louisa were ones of unrelenting loneliness bordering on despair. She finally met her half sister Evelina who had returned from Africa for the birth of her fourth child, the first three all having died at Kumasi in Ghana. However the two women found they had little in common and Louisa felt an unwelcome visitor from Wapping in the salubrious surrounds of Lambeth. She also wrote to her foster father in Scarborough hoping to put things back on their old footing, but his reply, when it finally arrived, seemed to further her sense of isolation from him, rather than lessen it. Likewise her friendship with Amelia was of little assistance. They had seldom been together since Robert Wilmot died in 1822, and the death of Sir Walter soon after Louisa moved to London in 1825 affected Amelia to the extent she became almost a recluse, unable or unwanting to respond to Louisa’s letters which she thought full of what seemed to her hardly problems at all. Their friendship would revive, but for Louisa it was missing at this critical time.

Most of all, she felt adrift from her father and from Sophia whom she felt monopolised his filial attention. In this she was probably correct – not so much because he favoured Sophia, rather that he was unable to cope with Louisa’s problems when she turned to him for help. Sophia, the strongest of the two at birth and seemingly still so 25 years later, took things easily in her stride and capably managed the Margate boarding house Turner had bought her. Louisa seemed to Turner exactly the opposite. In spite of growing up in a guest house, she seemed incapable of managing her own life, let alone a Wapping pub. She undoubtedly loved her boy Tom, but she was proving less than a good mother, or so Turner thought – spending more and more time with the lodgers from the Ship and Bladebone and the Star, the worst of influences.

In 1827 she decided to write to Amelia who replied suggesting that Louisa visit Farnley, which she did with her father’s help. Her stay at Farnley was a happy time for them both. Amelia had finally come to terms with Robert Wilmot’s death five years earlier which had left her depressed and a shadow of the sun-bonneted bright young thing skipping along the Scarborough sands – as Turner had painted her ten years before. Both girls realised they needed to lift their spirits.