Described as “the first exhibition of the artist’s work in a British museum since 1992,” the exhibition Transferences: Sidney Nolan in Britain opened on 18 February 2017 at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, UK and continues until 4 June. A news clip by That’s Solent TV can be seen here.

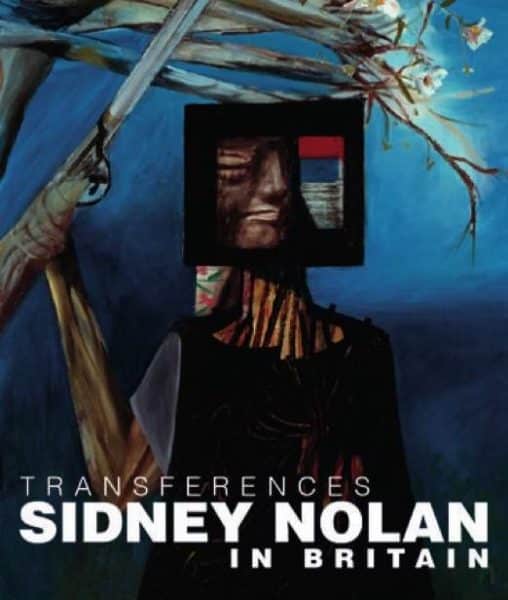

The catalogue, which is reviewed here, is edited by Rebecca Daniels with contributions from her and several others. It is an impressive publication (see the contents page illustrated below,) notwithstanding the omission of a listing of works in the exhibition itself.

The non-inclusion of a List of Works is rather curious, and something tomorrow’s art historian will likely regret given the claim that from this exhibition will emerge “an artist whose work was rooted in Australian myth and history,” but who “after he moved to Britain in the 1950s, …. arguably came to see his subjects through British eyes.”

Certainly it would seem to be mainly through British eyes that Nolan’s centenary is being observed world wide. The Sidney Nolan Trust has scheduled an impressive calendar of events throughout the year in a well placed endeavour to leverage heightened interest in Nolan because of the Centenary. The Trust’s bi-weekly Nolan 100 postings (selections of works from a hundred individuals world wide) are particularly engaging. In Australia on the other hand, no major public gallery is mounting anything of significant import.

None of this would likely have come as any surprise to Nolan himself, whose Australian-ness, Irishness, and Britishness ebbed and flowed as circumstance dictated. He would though, surely have found it curiously affirming that only one of the seven contributors to this catalogue about him “in Britain” is actually British – all others are Australian.

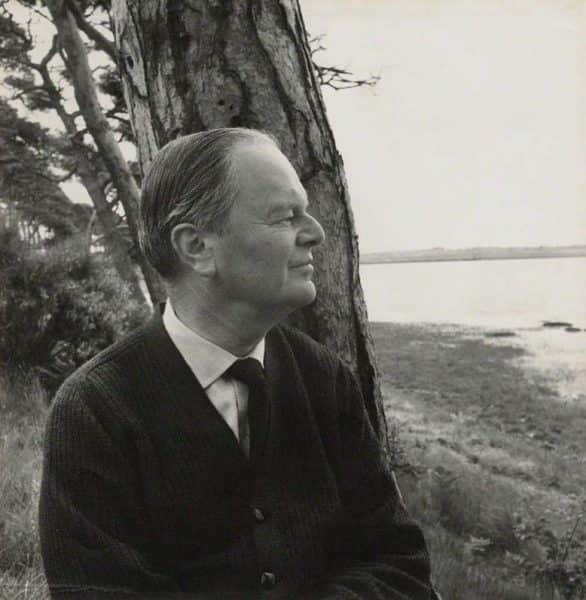

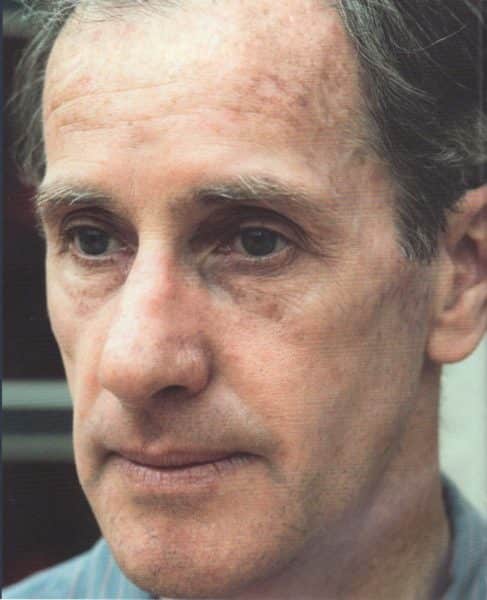

The catalogue itself presents well, its layout accessible with a wealth of colour images and well written essays in large, easily readable font. Standing out are some marvellous early 1960s photos of Nolan, particularly those by British dance and theatre photographer Zoë Dominic. I am unaware of these having been published before.

Turning to the essays themselves, Barry Pearce’s evocatively named Planet Nolan is a warm enthusiastic encapsulation of the man and his work, replete with fine phrases and fine feelings. It is clear from Pearce’s earlier writings that he holds Nolan’s visual genius in awe, and this and his belief that Nolan’s fate was “as an envoy to the entire planet” permeate this present essay. For a curator of Pearce’s standing, it must be comparative luxury – if nevertheless a challenge – to write about a painter he so admires, and whose art he so respects, in some 4000 words rather than five times that many in a catalogue for a major retrospective exhibition with almost 120 works (as in his catalogue essay Nolan’s Parallel Universe for the 2007 AGNSW exhibition Sidney Nolan.)1 Indeed planets and parallel universes seem apt descriptors for the stellar position of Nolan in Pearce’s sensibility, and after reading this essay one feels his sentiments are not misplaced.

The essay traces the major paintings, and major series of Nolan’s works, in the chronological context of his life, his loves and his locations, and the influence all three brought to his colossal output. It does so with an economy of words, using well chosen images along with telling quotations from Nolan’s own utterances to illustrate the various phases of his career. For its relative brevity, it is as succinct, yet as comprehensive an account, as any I have read on Nolan.

We see all the famous works: Ned Kelly, Mrs Fraser, Boy and the Moon (Moonboy), and half a dozen others. Then, without illustration for it defies representation on the single page, comes Riverbend I – “an elegiac, nine-panel masterpiece, arguably Nolan’s greatest,” says Pearce and I could not agree more. Indeed time may judge it one of the great works of the twentieth century. The following illustration does it little justice.

“Riverbend”, 1964-65, Sidney Nolan. Note that the size of the middle seven panels has been progressively reduced in this presentation.

“Riverbend I,” Pearce says, “stands supreme, a symphonic homage to Nolan’s childhood,” and he quotes from Nolan’s own words “… it is along this river that I was brought when I was about, I suppose about six weeks old. And I was fed by my mother … in a log cabin …” The painting itself and Nolan’s words strongly invoke for me these lines from Dylan Thomas’ Poem in October

“And I saw in the turning so clearly a child’s

Forgotten mornings when he walked with his mother

Through the parables

Of sunlight

And the legends of the green chapels”

Paula Dredge’s essay on the ‘tricky problem’ of Nolan’s paint shows just how innovative a technician Nolan was. We learn he used alkyd-based household paints (such as Dulux) most likely earlier than any other ‘name’ artist. These paints have been identified on Nolan works made in 1942, at least six years before Willem de Kooning used them in 1948 followed by Jackson Pollock a year later. This, and his willingness to experiment with and embrace other innovative techniques and materials as soon as they were developed, prompt Dredge to state “this places Nolan at the forefront of many key technical development milestones in the use of modern paint by artists in the second half of the twentieth century.”

Her analysis covers only Nolan’s early Australian years 1939-1953 and she concludes “there is no doubt much more to learn from the study of the materials in the studio (Nolan’s studio at The Rodd) followed by scientific analysis of the paintings.” Through a research residency at The Rodd, Dr Dredge will continue her studies during 2017 to encompass the final four decades of his practice. This must be an exciting prospect. In 2008 when speaking of the extent of his technical daring, Nolan’s widow Mary suggested “they’ll have great fun discovering what he did do.”

Unaware that they were contributing essays to the Pallant House exhibition, I invited both Barry Pearce and Paula Dredge to write for my Centenary tribute Imagining in Excited Reverie. Their essays in this catalogue stand as fine tributes to Nolan and I hope these might be able to be included in Excited Reverie.

Simon Pierse, whose essay Transferences looks at the critical reception Nolan’s art received in Britain, will be a contributor to Excited Reverie. His present essay draws on his masterly book Australian art and artists in London 1950-19652 and in particular shows convincingly, regardless of whether Nolan’s work was influenced by seeing his subjects through British eyes, that it was through British influences – particularly those of Kenneth Clark and Bryan Robertson – that critical reception and acceptance of Nolan and his work during the 1950s and 60s was achieved.

In a lively and perceptive account, the essay traces the milestones in Nolan’s march to British prominence. Clark regularly bought Nolan’s paintings to lend back to galleries and exhibitions, and his “immense importance and cultural influence” ensured that his endorsement of Nolan opened doors and overcame obstacles. They formed a close bond which matured into a lifelong friendship – notwithstanding Nolan’s propensity for conversation at Saltwood breakfasts which ran counter to Clark’s desire to read his paper in silence,3 and his perplexity at some of Nolan’s more esoteric works – reportedly enquiring of the Oedipus paintings, “what do they mean Sidney?”4

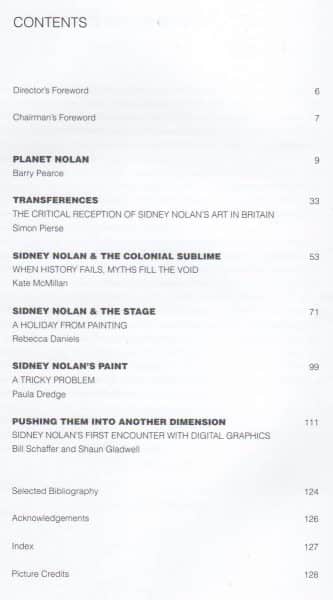

“XXIV Notes for Oedipus”, 1975, Sidney Nolan

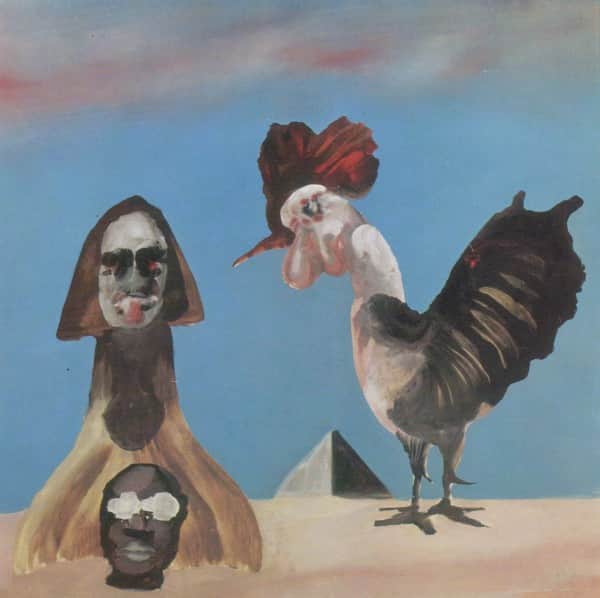

The essay includes the marvellous photo of Clark seen below. Is perhaps Sir Kenneth sniffing the Saltwood air for another antipodean genius?

Sir Kenneth Clark, 1964, by Janet Stone

Bryan Robertson, says Pierse, was perhaps of even more influence than Clark in furthering Nolan’s career. The 1957 Nolan retrospective at his Whitechapel Gallery was an overwhelming success, then in 1961 Robertson, Clark and Colin McInnes wrote the well-received Thames & Hudson monograph Sidney Nolan, and that same year at Whitechapel he staged the landmark exhibition Recent Australian Painting. Australian art was flavour of the decade and in 1963 when Marlborough Fine Art became his dealer along with the likes of Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud and Henry Moore, Nolan had truly arrived. The boom would last until what Kenneth Clark termed “the didactic snobbery of abstract art” carried all before it.

Rebecca Daniels’ essay on Nolan and the stage is noteworthy in more ways than one. First, several 1962 photos by Zoë Dominic of Nolan working on The Rite of Spring are quite magnificent, and little known; second, the quotes from Nolan’s presentation of the third Reynolds Lecture “Painting and the Stage” to the Royal Academy in 1988 give a fascinating insight into his approach to intellectual collaboration with others; and third, whilst each of Nolan’s relatively few (just nine) ventures in design for the stage have certainly been catalogued and much discussed previously, this well researched essay, concentrating only on his stage works, focusses one’s attention and allows an appreciation of just how significant and prestigious were Nolan’s achievement in this milieu. He was just 22, his entire exhibited work amounting to just one painting Head of Rimbaud in the 1939 Melbourne CAS exhibition, when he designed the set for Serge Lifar’s 1940 production of Icare for Colonel de Basil’s ‘Original Ballet Russe’ company – the set for Lifar’s first production in Paris in 1935 had been designed by Picasso! Eight years later he collaborated with Jean Cocteau in designing the set for a Sydney production of Orphée. For his first ballet commission in Britain he designed the sets and costumes for the celebrated 1962 Kenneth MacMillan production of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring at Covent Garden, in collaboration with the composer himself. Then came three operas directed by Elijah Moshinsky (who is preparing a tribute for Imagining in Excited Reverie, and has written No 15 in the Nolan 100): Samson et Dalila at Covent Garden, Il Trovatore at Sydney Opera House and Die Entführung aus dem Serail at Covent Garden again.

The text brings an immediacy, freshness and candour to Nolan’s collaborations and creative instincts for the stage, particularly with reference to the Rite of Spring production. Indeed we even learn that an early (and soon discarded) concept for the male costume featured an erect penis which was demonstrated for MacMillan when Cynthia Nolan “appeared, stark naked, modelling a huge phallus attached between her legs.”5 The essay provides well-reasoned support for Daniels’ contention that “Nolan’s deep passion for music, theatre and opera lay at the base of his set design work and deserves better recognition.”

In their essay Pushing them into another dimension, Bill Schaffer and Shaun Gladwell discuss and analyse Nolan’s first encounter with digital graphics in 1987 when he participated in Painting with Light, “a documentary series produced for the BBC to showcase the real-time capacities of Quantel Paintbox, a breakthrough video graphics system at the time.” Their account makes for a most interesting read, particularly their comparison of the different attitudes of Nolan and David Hockney to the system, and, as they point out, the fact that the six episodes (one per artist) are records of the creative process of each. In the case of Nolan it is thought that no other such record exists.

However as fascinating as the essay is, it pales when compared with the film itself (which is now available online and can be seen here.) I read the essay before seeing the film, and think I would rather have done it the other way round in that the essay perhaps somewhat mutes the excitement of the film, which I found quite riveting. We see Nolan excise images from various works, shrink them, enlarge them, re-colour them, then position them on others. Not, mind you, that this conflating of images was new to him. In 1974 he took the Rosa Mutabilis image and superimposed it on Moonboy to produce Homage aux Prix Nobel.6

.

“Rosa Mutabilis”, 1945, Sidney Nolan, Heide Museum of Modern Art collection

.

.

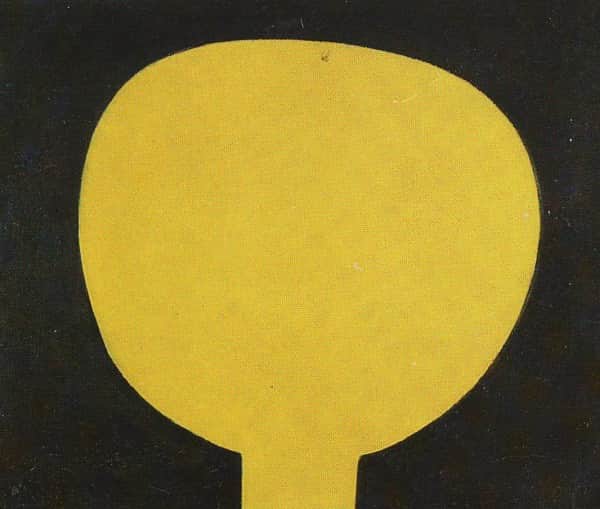

“Moonboy” or “Boy and the Moon”, c 1939-40, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection

.

.

“Homage aux Prix Nobel”, 1974, Sidney Nolan

.

Kate McMillan’s essay on Nolan and the colonial sublime is particularly interesting. She makes the point that the colonial sublime in Australian landscape painting, Nolan’s included, touching as it does on the terror and vastness of the great unknown, is inevitably painted from a post-colonial Eurocentric perspective of coloniser/settler/pastoralist and not from perspective of the first peoples. This would seem indisputable.

She continues “it is incredible to imagine that the most iconic of Nolan’s images were painted from the amenable surrounds of British life – utterly bereft of the harshness of outback Australia. I believe this distance from his own culture enabled a ‘seeing of it’, that he could absolutely not have done this had he been immersed in Australian life.”

Issue can be taken with this conclusion which seems to insufficiently recognise those ‘iconic’ images completed before he first left Australian shores in August 1949: the Wimmera works, the ‘kitsch heaven’ of St Kilda, the first series Kellys, the first Mrs Frasers and the Inland landscapes. They don’t come much more iconic than these! And while the drought and carcass works may have been painted after he had breathed British air for ten months or so, they too were done in Australia. The conclusion also seems to largely ignore his camera, ignore just how much time Nolan did spend on site, and most significantly, does not consider the incredibly eidetic potency of Nolan’s visual memory.

Take Nolan’s Riverbend. I am certain that the Thames at Putney, where it was painted, had absolutely no effect on Riverbend. Nolan knew every inch of Daunt’s Bend at Toolamba on the Goulburn River, the site of Riverbend, where he fished with his father. During 1963, the year he commenced this masterpiece, he had camped on the Bend near the old wooden road bridge for a week. Sit in the mud at Daunt’s bend, (and Simon Pierse and I have done just that – albeit unintentionally), and all about can be seen every shaft of sunlight, every patch of dappled shade, every strip of bark, and every inch of muddy water which Nolan infused into these, his very own, ‘parables of sunlight and legends of the green chapels.’

Panels 2 and 3 of Nolan’s “Riverbend” bookending a photo of Daunt’s Bend, Toolamba on the Goulburn River where Nolan fished with his father.

But what is particularly challenging and confronting in Kate McMillan’s essay – more than confronting, it is gut-wrenching – is the sheer logic in her analysis of how our art of landscape has effectively been complicit in “the absorption of certain histories at the exclusion of others.” If history is seen as a chronicle of dispossession, then the so-called history wars surely centre on this selective absorption of one history rather than another. “Only history-telling conducted in the margins,” she says, “has voiced the violent, state-sanctioned genocide of over 350 language groups across the continent.”

Quote after heart-rending quote assail the reader:

It is not surprising that the oral histories of invasion still shared by Aboriginal people today resemble something from Dante’s inferno – literally hell on earth.

A sense of history is derived not from 60,000 years or more of indigenous storytelling and culture, but in the narratives of Europe.

…. the erasure of an entire population should surely speak …. of the on-going historical erasure of settler violence in Australia.

…. despite hundreds of massacres recorded – the last one in 1928 – not one photograph or painting exists of them. The absence is terrifying. The imaging of Australian history has been so partial, and in many instances simply false, that it is only ever possible to view Australian landscape as anecdotal, part of a broader nation-building project closely aligned to propaganda.

Turning to the drought photographs and paintings Nolan made in 1952 and 1953, she sees in their haunted images not just pastoral relics of a devastatingly bad drought, but a visible record of a “place unsettled and unsettling”, a badland.

Sidney Nolan, “Carcass”, 1952

Nolan’s images “record the presence of a bad spirit”; indeed they portray “the rotting carcass of colonialism in miniature” and “speak back to a nation about itself, and to Britain of its colonial legacy.”

Sidney Nolan, “Drought Skeleton”, 1953, collection AGNSW

She stops short of seeing the withered horse and cattle carcasses as a substitute, a metaphor perhaps, for the countless massacred Aboriginal bodies not left beneath the withering sun to desiccate, but burned to remove evidence of their slaughter. Once having made that connection though, who will ever again be able to look on these images of Nolan’s with the same eyes? Sidney Nolan and the Colonial Sublime will live on in your consciousness.

Throughout his life Nolan was masterful at revealing only as much of himself as he wished, and his success in self-concealment is evident in much of what has been written about him over the years. This catalogue for the Pallant House exhibition, illuminating and interesting as it is, proves to be no exception. That said, it is an informative, enjoyable and at times fascinating read.

However Sidney Nolan in Britain gives us little glimpse of the attitudes of Sidney Nolan to Britain and to the British. Perhaps that is only to be expected – transferences do not necessarily lead to allegiances, and there is only so much of a life that can be revealed in six relatively short essays. Could the Sidney Nolan seen in the works on the walls of Pallant House ever be the same Nolan seen in his diaries, note books and some late interviews? Do the paintings reveal the man whose attitudes to things British were perhaps far removed from Establishment mores?

Thus for example, Nolan said of his 1983 Order of Merit award, and of Graham Greene’s OM in 1986 (despite Greene’s continued friendship with Kim Philby who was his minder during his espionage activities), “Well he was still made OM wasn’t he? The Queen must have been totally aware of his position … and also aware of mine. So it makes it interesting, it makes England quite an interesting place in spite of its defects.”7

Nolan promised the sacked Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam he would paint The Dismissal if Whitlam came clean about CIA involvement in his overthrow.8 He confided to his diary words to the effect that he would do to Sir John Kerr the opposite of what he did for Kelly,9 and speculated on the identity of the vice-regal conduit between Kerr and the Queen.10

And speaking of Rupert Murdoch, he observed “his politics turned around quite quickly. Well, all you can say to that sort of thing is that they’re lost to the fold.”11 This opinion though, did not deter him painting a second Riverbend for purchase by Murdoch to adorn the News Corp boardroom in New York – the larrikin was ever lurking.

This perceived failure in the catalogue to portray Nolan the person in Britain, will perhaps be set to rights at the Nolan Symposium scheduled at the Royal Academy for 22 April, the actual centenary of his birth. The programme suggests a broad more complete image may well emerge from its examination of Nolan’s work and life from a multicultural, global perspective in the context of him examplifying the artist as polymath, with expertise and innovation across different subjects and approaches.

Exactly 24 years to the day before the participants gather for this RA symposium, another congregation gathered just across the road from the Royal Academy in St James’ Church, Piccadilly for Nolan’s memorial service. The recessional hymn was William Blake’s And did those feet in ancient time, best known today as Jerusalem with its familiar musical setting by Hubert Parry. Its very last words “in England’s green and pleasant land” seduce one into thinking that over his last 40 years Nolan may indeed have come to see his subjects through English eyes.

That however, is to mistake the latter day flag waving, chest thumping and football fevering generated by Jerusalem for Blake’s revolutionary intent when writing it 200 years ago. The “dark satanic mills” were real for Blake, as was his vow to not cease from mental fight, nor let sword sleep in his hand: Till he had built Jerusalem, in England’s green & pleasant land.

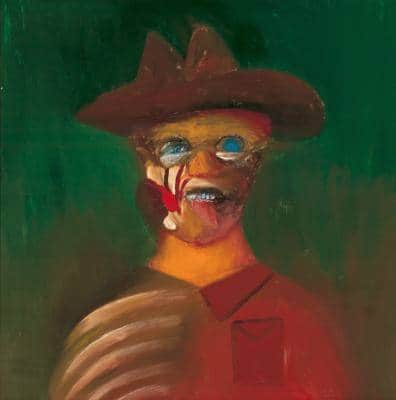

And, at least in my thesis, these sentiments remained real for Nolan. It seems somehow appropriate that this exhibition of Nolan’s work is in Chichester where at the Assizes in 1803 Blake was acquitted of charges of assault and uttering seditious and treasonable expressions against the King – “Damn the king” he had said, “the soldiers are all slaves.” Nolan too protested the soldier’s lot, saying of his 1973 slouch-hatted Ern Malley portrait, “He’s got a shell thrust in his face and I’ve made him half a carcass to show he is half ghost and half what happens when you go to the war and you come back.”12

Sidney Nolan, Ern Malley 1973, Art Gallery of South Australia

Appropriate too that it was a 1939 painting The Eternals closed the Tent, inspired by a line from Blake’s Book of Urizon, which captured Serge Lifar’s attention and secured for Nolan his first commission – and that an international one – to design the set for the Ballets Russes production Icare.

A school friend of mine who lived and worked in Britain for some 30 years from the 1970s, and who, like Nolan, owned a fine old English manor house, enjoyed recounting how he would practice his Australian accent before the mirror so he could “use it on the Poms when the cricket started.” One can imagine Nolan, who is said to have stayed up late at night listening to Neighbours for its Australian accents, practicing his British accent before the mirror so he could use that on the Poms as occasion demanded.

One wonders just what Nolan would have thought of today’s shenanigans? Would he have enjoyed the British attention being danced on his Centenary, and been unsurprised (as before) at the dearth of any Australian effort? Perhaps – indeed probably – but who knows.

Now 25 years in company with Karl Marx in Highgate cemetery, I rather suspect that were he alive in the world he’d find today, he’d be painting furiously – whether with Ripolin or spray can – on a masterpiece. A Nolan Dismissal, as I imagine it, would echo Blake perhaps more than Rimbaud. To borrow words from the catalogue’s forward by Artistic Director Simon Martin, it would be imbued “with universal themes and archetypal characters.”

And he would be seeing his subjects not through British eyes, nor through Australian eyes, not even through universal eyes; but rather with that unique vision, defying categorisation, that came through Nolan eyes.

We see them here.

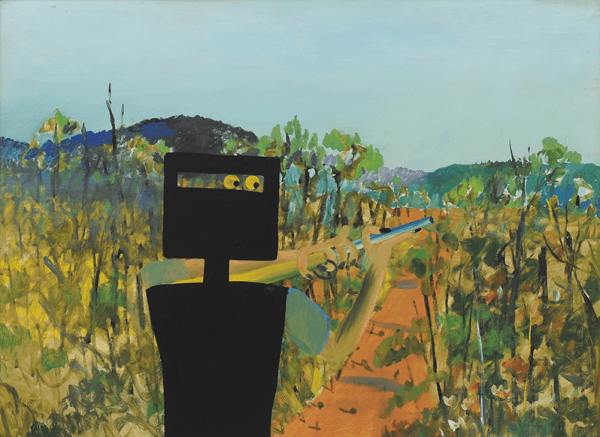

“Head of Soldier”, December 1942, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection.

“First Class Marksman”, December 1946, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW collection.

Photograph of Sidney Nolan, 1962, by Zoë Dominic

END NOTES

- Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, Sydney AGNSW, 2007.

- Simon Pierse, Australian art and artists in London 1950-1965, Farnham UK, Ashgate, 2012.

- ibid., p. 196.

- Nicholas Usherwood, Nolan’s Nolan: A reputation reassessed, London, Agnew, 1997; Notes to Item 80.

- quoted from Jann Parry, Different Drummer: The life of Kenneth MacMillan, London, Faber and Faber, 2009, p. 243.

- In Sweden to accept the Nobel Prize on Patrick White’s behalf, Nolan was asked to be the Australian among 33 national artists producing works on paper in homage to the prize. Galerie Börjeson in Malmö, Sweden invited one artist from each country which to that point had produced a Nobel laureate to submit a work. They were sold in limited editions and were later all published together with other works of each artist. See Moderna Mästare, Galerie Börjeson, Malmö, 1978. Nolan’s work is on p.327.

- Sidney Nolan interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 1991.

- In his diary on 26 March 1991, at the Rodd, he wrote: “As Kenneth Clark said to me in Ireland, my Troy triptych was alright, but my Gallipoli paintings were perhaps not satisfactory because you could not paint history until everyone is dead. Well they are beginning to be, he his, and this morning March 26 – there are obituaries of John Kerr in all the papers. Preceded in each case of a larger obituary of Archbishop Lefebre ‘what you might call a fascist archishop. Into what category should one put Kerr with his Council of Civil Liberties and their dubious sponsors? My promise to Whitlam to paint the history of the whole affair” (see Papers of Sir Sidney Nolan, National Library of Australia, Canberra, MS 10245, Box 1); see also Sidney Nolan interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 1991.

- Aware of Nolan’s intention to paint the Dismissal, I contacted Damian Smith, inaugural archivist at the Rodd, and asked if he was aware of any sketches or studies on the subject of a Dismissal painting. He advised being aware of nothing other than a diary note regarding Sir John Kerr and how Nolan might treat him, (Damian Smith, email to author, 13 February 2017).

- In London on 5 April 91 his diary note reads: “And so on to Kerr, Whitlam and the dismissal and today obituary of de Lisle who I thought was the go between Kerr and the Queen. So all the characters in the plot are now dead, almost, and the whole thing ready to paint.” (see Papers of Sir Sidney Nolan, op.cit.).

- Sidney Nolan interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 1991.

- Sidney Nolan, Sidney Nolan and Ern Malley, Beyond is Anything, 1974; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, Melbourne, Viking, 2007, p. 259.

2 Comments

Join the conversation and post a comment.

I have tried to buy this catalogue to be told it is not available in Australia

could you please advise how to purchase tan other UK

Michael,

The catalogue can be obtained from the Pallant House Gallery Shop (https://pallantbookshop.com). Cost is £19.95 plus postage to Australia £20