This is a transcript of a lecture given by David Rainey on 25 July 2018 at the Anglican church of St. Mary-in-the-Valley, Canberra. It includes full references not given in the presentation. Nolan’s own words are frequently quoted and in this transcript are shown in bold. Please NOTE that the text remains as spoken and consequently follows, rather than precedes, the image to which it relates.

Good evening all. Thank you for coming out on such a cold night – especially those of you whom I know have some difficulty with Sidney Nolan.

Perhaps tonight might change that, or perhaps not. But I would say this. Do go into the National Gallery where 26 Kelly paintings hang together in their own room – although not at the moment, they’re headed to Perth. Look at them and imagine them without any figures. Imagine just the landscapes.

I think few artists, before or since, can hold a candle to Nolan when it comes to capturing the light and the colour of the Australian bush and the outback.

At the outset I must confess to being neither theologian nor art historian. Perhaps that’s why I’ve easily reached two conclusions: first, that there’s more to Nolan than meets the eye; and second, that there’s more to the Divine than meets the eye.

These two convictions of mine are really what this talk will be about.

Well. Sidney Nolan. Say the name, and what do we think of? Ned Kelly of course.

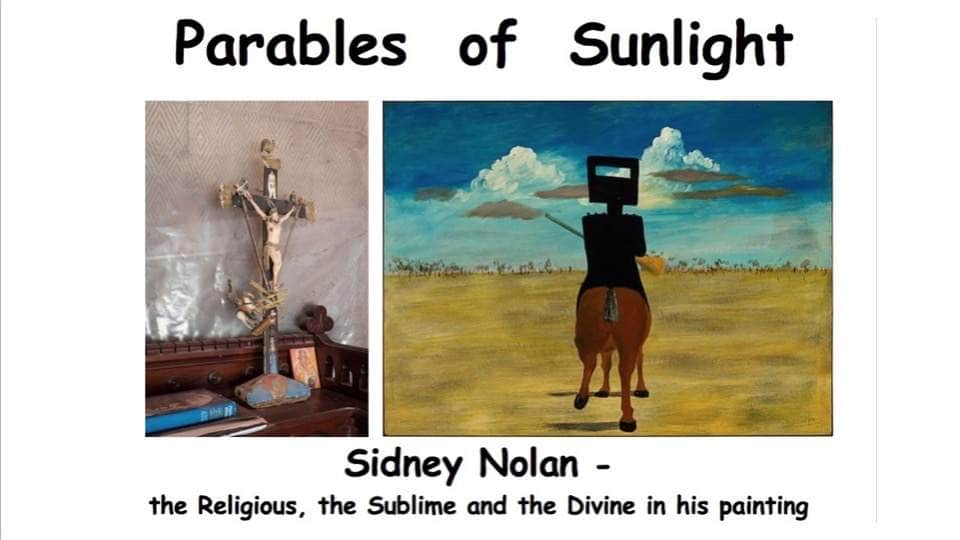

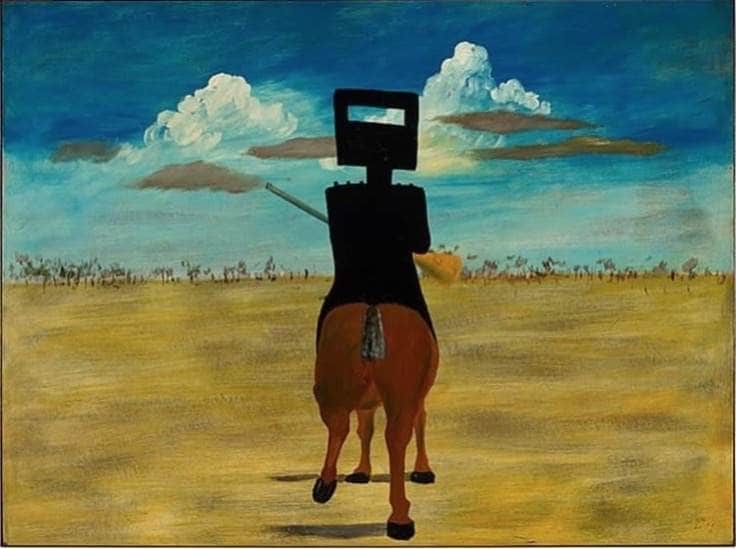

Sidney Nolan, “Ned Kelly”, 1946, collection NGA

And here he is – a mounted Kelly gazing out into the distance. This is certainly Nolan’s most famous image. An iconic image if ever there was one.

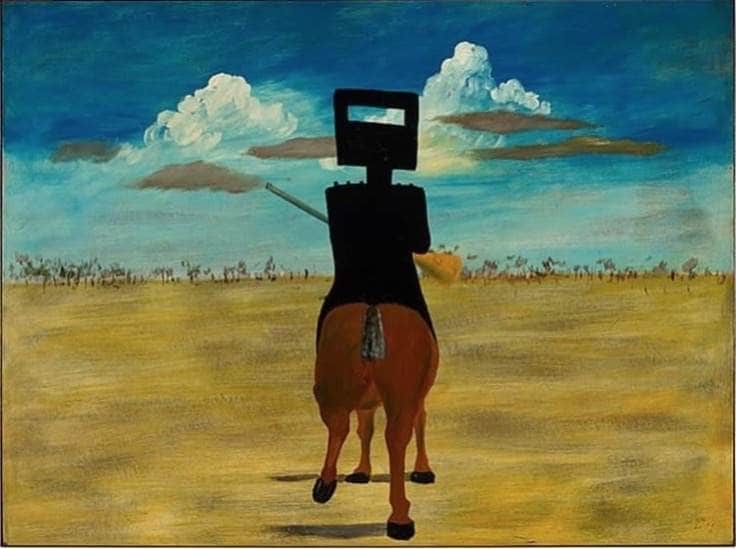

Perhaps the least likely thing most people would associate with Nolan is a crucifix.

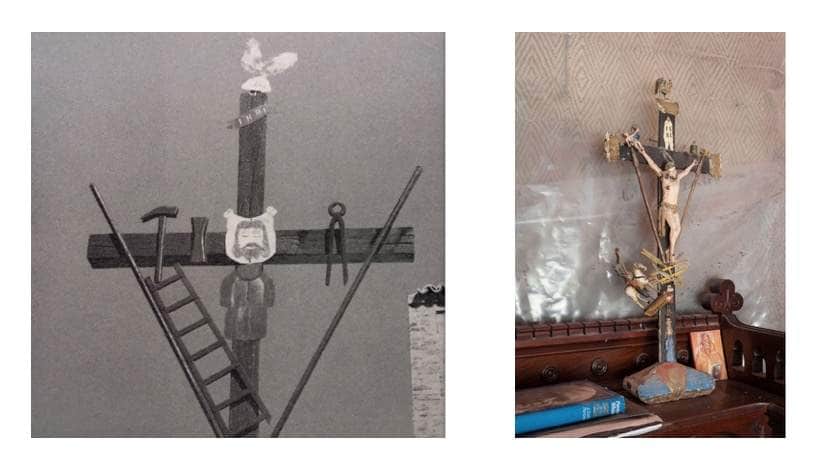

Something like this. It’s Nolan’s own in fact, from Italy, and he most likely got it there during the 1950s. We’ll see how it’s influenced his works – indeed it was in his studio when he died in 1992.

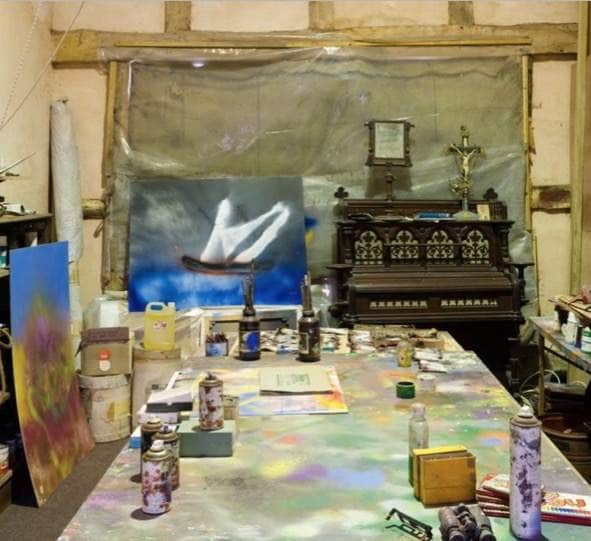

It’s still there sitting on an organ in the corner of the old barn at his home near the Welsh border.

Why the Religious, the Sublime and the Divine in his painting? Why not simply his painting of the Religious? Well, Nolan had some difficulty in detecting overly much divinity in lots of the religion he observed.

Although I’ll talk separately about the Religious, the Sublime and the Divine, I’m not suggesting that these categories are mutually exclusive. We’ll certainly find the Divine in both the other two.

But before we look at the Religious, let’s first take a brief look at Sidney Nolan himself.

(L) Sidney Nolan, “Ned Kelly”, 1947, collection NGA; (R) Sidney Nolan, “First-class Marksman”, 1947 collection AGNSW

Yes, he painted Ned Kelly up there on the left. And he holds the auction record for an Australian artist – $5.4 million for First Class Marksman on the right.

Just looking at those two paintings, where do you think Kelly’s looking in the work on the left? Ahead, of course – but hold on. You can see right through the helmet to the clouds beyond. There are no eyes in this most famous Kelly painting like there are in First Class Marksman on the right – and those ones are looking backwards! We’re entitled to ask what’s going on.

I won’t try to push for meanings too much, but I do hope you’ll perhaps take a fresh look at Nolan, and seek meanings as well as just looking at the images, because painting can be about more than reproducing an image.

It’s also about communication. Two days after Nolan died his friend and fellow artist Albert Tucker talked with Philip Adams on Late Night Live about Nolan’s imagery and Tucker said ”The image is the most primal form of communication.”1 Nolan himself has said:

“Painting is an extension of man’s means of communication. As such, it’s pure, difficult, and wonderful.”2

But back to Nolan the man. Let me give a short biopic.

A SHORT BIOGRAPHY

He was born in April 1917, the son of a tram driver who was also an SP bookie. The oldest of four, he had two sisters and a brother.

His ancestry was Irish – his policeman grandfather Bill migrated to Australia in 1853. But his line was Northern Ireland Protestant, not the Catholic roots of Ned Kelly. Nolan never bothered to correct this misapprehension and over time it served him well.

He grew up in St Kilda – he called St Kilda “my Kitsch Heaven”. He’d left school by 14 and worked in the design office at the Fayrefield Hat Company.

Although he started night classes at the National Gallery Art School when he was 17, his intellect was more stimulated by books in the Public Library Reading Room next door. He’s said

“I’d go in to draw and I’d draw for half an hour, and then I’d think, Oh, bugger it, I’ll go upstairs and read.”3

He absolutely devoured literature – the likes of poets William Blake, Beaudelaire, Rimbaud, Rilke; writers like Proust, Lawrence, James Joyce; philosophers like Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche.

This is Nolan speaking in his mid-40s:

I just read as much as I could stomach … Ozenfant … Spengler … Dostoevsky … All this was for me incandescent. The first Picasso I saw was a kind of double-eyed thing … and between that and the van Gogh and a bit of philosophy upstairs it was clear there was no sense in hanging onto anything whatsoever, you know intellectually … you might as well go the whole hog. One of the first books we all read was Wilensky, then the Bible.4

One of the students at the National Gallery School was Elizabeth Paterson

Nolan and Elizabeth at St Kilda, the pier in background, c. 1940. Photo courtesy Amelda Langslow

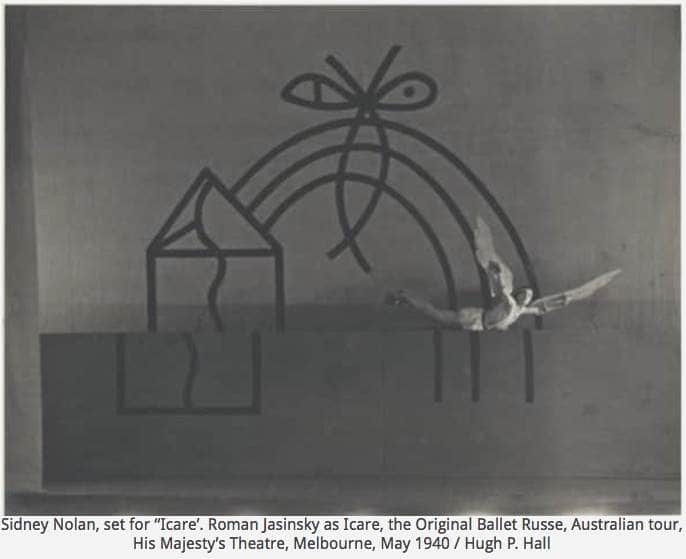

whom we see here with Nolan by the pier at St Kilda. Both were artists, she more conventional than he. They were married in December 1938 and struggled financially; they ran a pie shop, lived cheaply on a farm for a year…. and they painted. A big success came in 1940 when she designed the costumes and he the set for a Ballets Russes production of Icarus. Their daughter Amelda was born in 1941, but the marriage was not to last much longer. In fact Elizabeth never returned to their home after the confinement, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, Nolan’s attempts at reconciliation didn’t succeed.

One reason for this was the influence of John and Sunday Reed who were extremely wealthy patrons of the arts. They lived on acreage in a farmhouse on the banks of the Yarra River in what was then rural Heidelberg. The home was nicknamed Heide, and here they supported artists financially, emotionally and intellectually.

Nolan first met the Reeds around the time he and Elizabeth married. He was seeking financial support, they were seeking a potential genius to champion. It was a match made in heaven! Soon after his marriage collapsed in 1941, Nolan moved in. He lived with the Reeds at Heide in a ménage à trois for 6 years. He was conscripted into the army in early 1942 and two years later went AWL.

This photo shows them around the 1946 Christmas table. Nolan’s on the left, and John and Sunday Reed look at each other across the table.

All in all it was an incredible period – artistically and intellectually so productive, yet so fraught emotionally. All of them would carry life-long scars.

Nolan finally left Heide in July 1947 and travelled in Queensland for six months. He went to Sydney at New Year and there he met up again with John Reed’s sister Cynthia. They were married within 3 months.

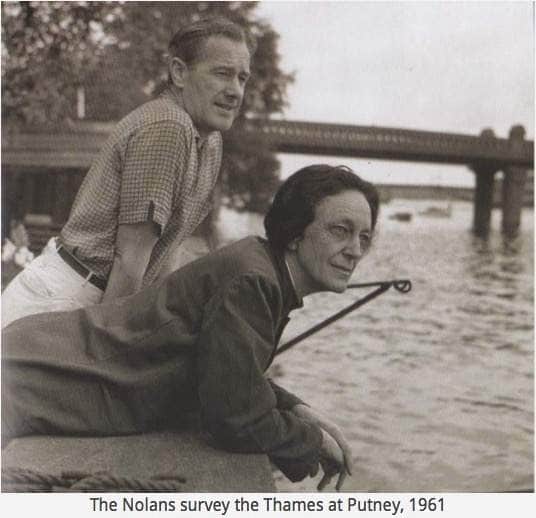

With Cynthia’s inherited wealth the Nolans could travel. First, in 1949 to outback Australia. They flew to and over the Centre and it was a revelation for Nolan. Then overseas in August 1950. They moved to England permanently in 1953 and thus began a period of consolidation that lasted almost 25 years. He painted, she managed. It was a creative, functional and effective partnership. Here they are at their home in Putney on the banks of the Thames in 1961.

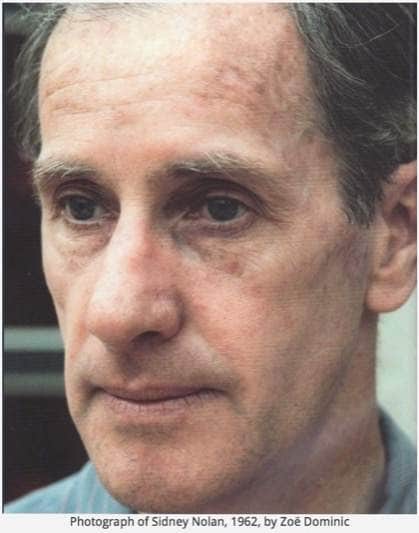

This photo of Nolan was taken the following year. He’s 45 and in the middle of an incredibly creative period. They travelled extensively. Australia almost every year. Exhibitions here and within Europe and in the USA. There were special visits to special places.They lived on the Greek Island of Hydra for 9 months in 1956 and it was here Nolan met the famed war correspondent Alan Moorehead who interested him in Gallipoli and in 1964 would take him to the Antarctic. Their travels continued: Africa, China, always criss-crossing Europe.

Then in 1976 Cynthia suicided. It was a desperate period for Nolan. The marriage hadn’t been particularly happy for some time, but her death left him shattered.

He married again in 15 months, to Mary Perceval, the painter Arthur Boyd’s youngest sister, who Nolan had known since she was a young girl. In this photo they sit at Heide just a few months after John and Sunday Reed had died.

The last 15 years of his life were both contented and productive, although his paintings from this period are little known. We’ll see some of them soon. Their time together included much travel and what remained was shared between their county home in the Welsh borders and their Thames-side apartment in central London.

This is Nolan in 1987 on the balcony of the Whitehall Court apartment and there’s Big Ben in the background.

It’s a long, long way from the Public Library reading room in Melbourne in 1937!

But his quest to seek out knowledge, and learning, and, to be fair – wealth and fame also – never really abated. His life almost seems an intellectual, perhaps also a spiritual, quest. He received many honours, a knighthood, honorary Doctorates, and he had a circle of friends and acquaintances that reads like a Who’s Who of the learned and the famed.

I’ll quote from Nancy Underhill’s autobiography of Nolan that was published 3 years ago:

“Nolan established several close personal friendships during the 1960s … Because a high proportion of these friends were famous, the view has circulated that Nolan was an opportunist who somehow hoodwinked people into thinking he was as interesting as they were … “ Nancy Underhill thought otherwise and so do I. She “simply did not believe that Patrick White, Kenneth Clark, Benjamin Britten, Robert Lowell, Yehudi Menuhin and Alistair McAlpine were the sort to be taken in by manufactured charm and the sprouting of second-hand views.”5

He died in November 1992 aged 75 and is buried here in Highgate Cemetery just 60 or 70 yards from Karl Marx.

THE RELIGIOUS

We’ll talk about how “religious” Nolan was in a little while. But first let’s look at some paintings.

Sidney Nolan, “Italian churches”, 1955

We’ll find few paintings like this one of Italian churches which is almost a tourist view. There are very few that are just churches without some added layer of meaning.

As we progress I’ll sometimes quote Nolan’s own words about a particular painting, or about painting in general.

Nolan did talk a lot, but in 1970 he said this:

“I’d rather paint what I have to say than say what I have to say.”6

Angels

So what’s Nolan saying in his paintings of Angels?

This work from 1941 is the first painting of Nolan’s ever published.7 It’s called Woman and Tree, also Garden of Eden, and it’s widely regarded as a painting celebrating the flowering of the love affair between Nolan and Sunday Reed.

I disagree with that interpretation. I’m certain it owes much more to his distress at the failure of his marriage and to his feelings for his first wife and their daughter. Even more, in my view it draws heavily on religious verse by the German Catholic poet Rainer Maria Rilke whose works Nolan knew well.

Rilke’s poem Annunciation (Words of the Angel) begins like this:

You are not nearer to God than we,

and we are far at best,

yet through your hands most wonderfully

his glory’s manifest.

From woman’s sleeves none ever grew

so ripe, so shimmeringly;

I am the day, I am the dew,

you, Lady, are the Tree.

Woman and Tree is one of several similar works by Nolan done during a 12 month period from around mid 1941.8

Here are some more:

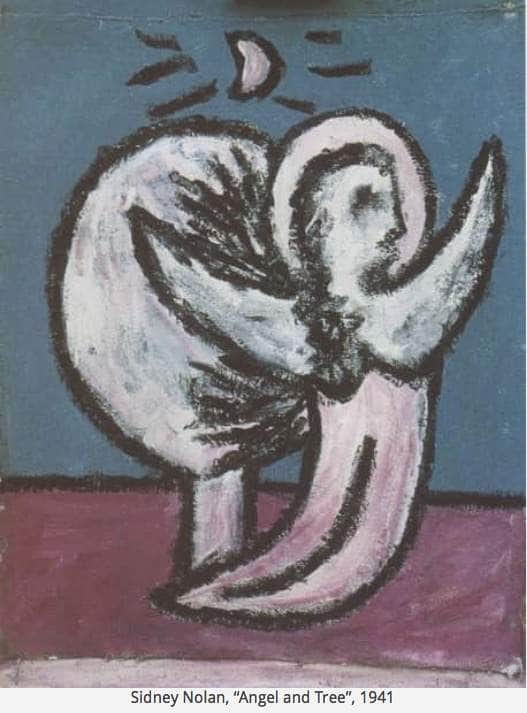

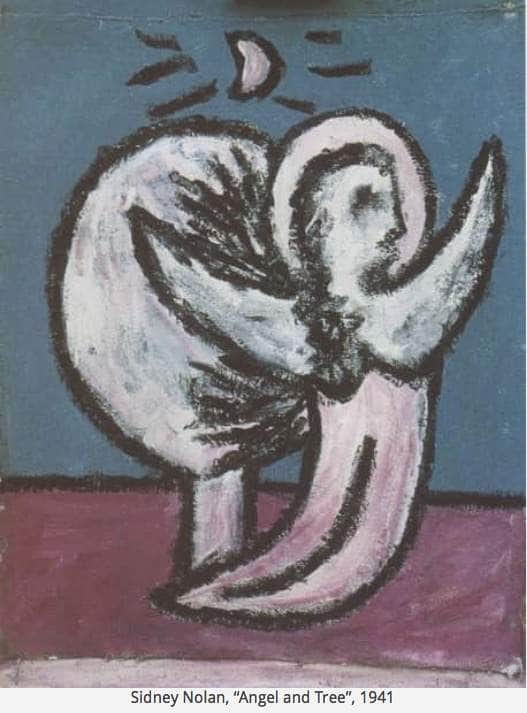

This is Angel and Tree

This one is called Garden of Eden

At this time Nolan also used discarded roof slates to paint a number of quite extraordinarily simple and evocative little images of angels. Here are two of them:

Art historian Jane Clark says this: “Swiftly executed, utterly – almost naively – simple …. sometimes Nolan’s angels swing through the air like acrobats …. Nolan recalls that Rilke …. had a special impact on his imagination at this time – with images of lovers, angels, hands picking flowers and tingling feet.”9

There’s a deal of speculation as to the source of Nolan’s angel imagery.

I’m sure one source is the Ballets Russes production of Icarus for which Nolan designed sets. Here we see the winged Icarus flying – just like one of those angels.

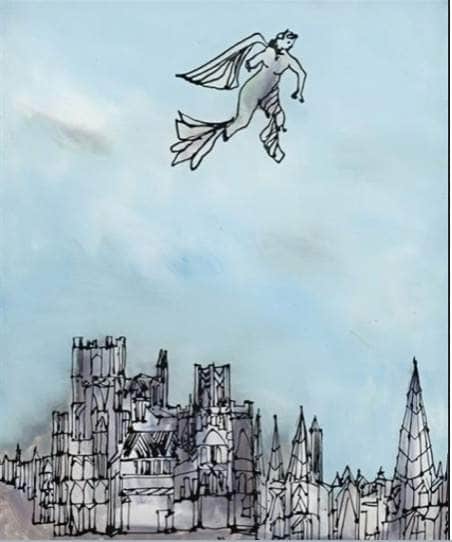

Sidney Nolan, “Angel over Ely”, 1950

The angel was still there in 1950, hovering over Ely Cathedral.

Sidney Nolan, “Angel over Ely”, 1950

Let’s now look at a second category of religious works …

Christ Crucified

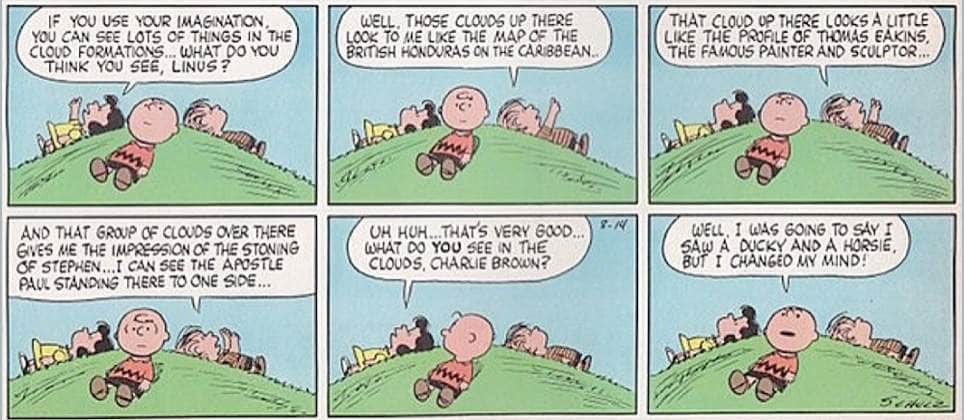

Christ crucified. But before we do, here’s a cautionary tale.

I’m sure many of you remember the cartoon strip Peanuts. Lucy was always the mother hen organiser-come-villian; her brother Linus the suave intellectual, a font of all knowledge; and Charlie Brown was a nice guy, their often-less-than-welcome reality check.

In one strip the tree of them contemplate cloud formations.

“What do you see in the clouds, Linus?” asks Lucy looking up.

“Well” says Linus, “those clouds up there look to me like the map of the British Honduras in the Caribbean. That cloud looks a little like the profile of Thomas Eakins, the famous painter and sculptor, and that group of clouds over there gives me the impression of the stoning of Stephen – I can see the Apostle Paul standing there to one side”

“And Charlie” she asks, “what do you see?”

“Well” mumbles Charlie Brown, “I was going to say I saw a duckie and a horse. But I changed my mind.”

So I’ll tread gently with my opinions.

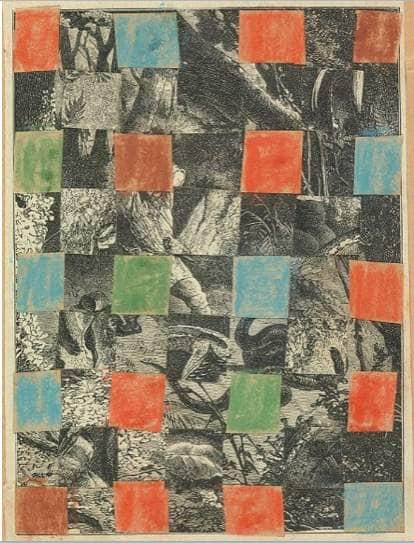

Sidney Nolan, “Christ cruicified”, December 1940

Now to this second category of religious works. Here we have an early work by Nolan, a collage from 1940. He’s inscribed it “Christ crucified”.

I don’t attempt to explain it – other than to say it illustrates, if nothing else, that matters of profound religious significance were part of Nolan’s frame of reference. And not just in common descriptive terms, but in a more esoteric religious phraseology like “Christ crucified” rather than simply “the crucifixion of Christ.”

Remember that Nolan says he’d rather paint what he has to say, than say it. What’s he saying here?

And why did he take the photo on the left in Calabria during the 1950s? As we see here, the small crucifix in his studio is quite similar. Nails, hammers, pliers and ladders – all work tools of both carpenter and crucifier.

Sidney Nolan, “Crucifixion”, 1955, private collection

An image like this reappears over the next 10 years or so in a series of stark works with the crucifix superimposed on the Mediterranean, on a Tuscan hillside, or on scenes of destruction from the second world war.

What is this man who paints what he has to say painting here? The head of Christ without a body.

Sidney Nolan, “Crucifixion”, 1956

Or here? Here we see that the head has morphed into the shape of an artist’s palette. The eyes are downcast. Is he saying something about the role of the artist – what it should be, or what it is?

Sidney Nolan, “Italian crucifix”, 1955, collection AGNSW

He also said

“I’m a kind of ‘think’ painter. The emotions are the heat to make the steam, but the steam is in the thinking.”10

What’s Nolan thinking here?

Sidney Nolan, “Crucifixion”, 1955, collection Worcester College, University of Oxford

What’s he saying when he uses these rustic Italian crosses that still dot the Italian countryside.

Like this one on the facade of a village church in the Abruzzo region east of Rome.

Sidney Nolan, “Crucifixion”, 1956, collection Hamilton Art Gallery, Vic

Images like this pose many questions.

Sidney Nolan, “Italian crucifix”, 1955

Perhaps one answer comes from Nolan himself. Speaking about the Italian Fellowship he got, he said

“It was to go and paint the frescoes that had been destroyed in the Padua Chapel – Mantenga frescoes that had been bombed during the war. I had seen photographs, and I had the rather grandiose idea that I could paint this as a comment on war.”11

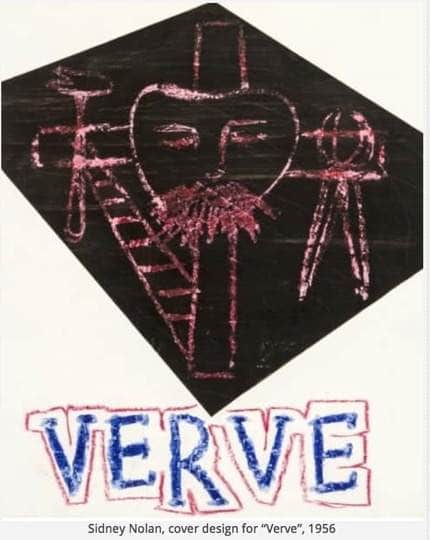

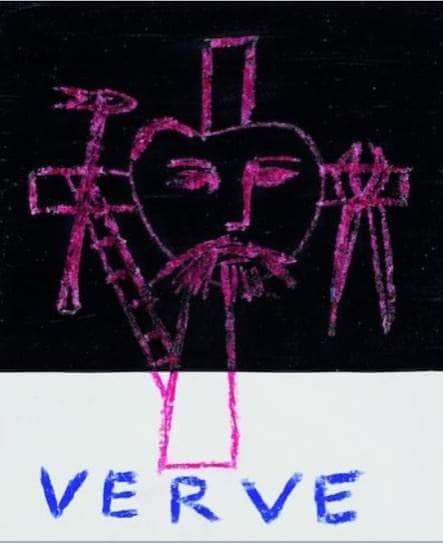

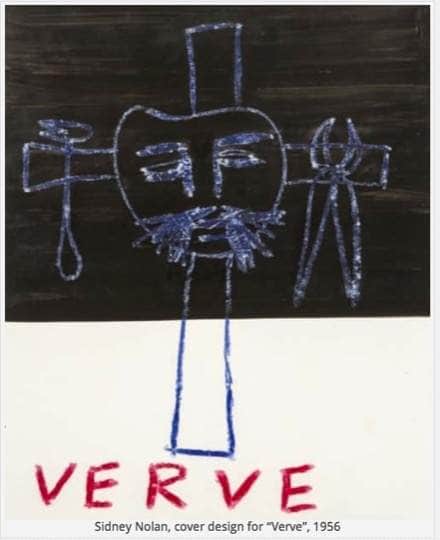

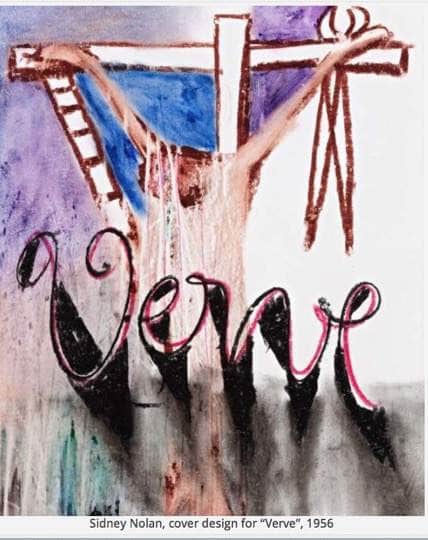

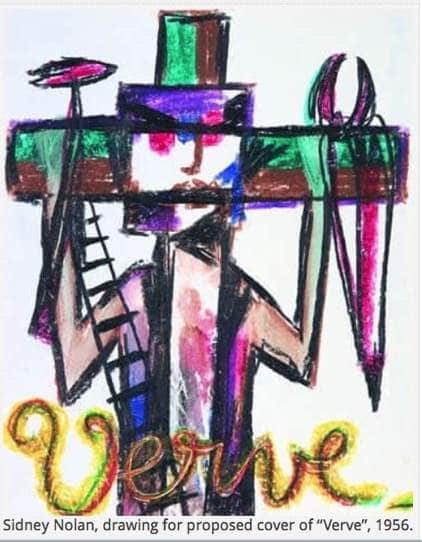

Now to the magazine Verve. This was a modernist-styled Parisian art magazine published for 20 odd years from the late 1930s. Its covers were done by the most prominent modernist painters: the likes of Picasso, Chagall, Matisse, Bonnard. In the mid 1950s Nolan experimented with several cover designs using this crucifix motif, but they were never taken up.

Here’s another ….

and another.

In this one, he paints the complete body of the crucified Christ.

And here the body has the Kelly helmet. What’s our ‘think’ painter thinking here?

Sidney Nolan, “Kelly”, 1959

And what’s the man who likes to paint what he has to say, saying here?

Is it, more coventionally, that Christ’s death has atoned for Kelly’s sins? Or does he see Kelly as a Christ-like figure?

I’ve no idea what’s in Nolan’s mind with this imagery – but I do say that he knew what he was about. Nolan’s images are never idle daubings – indeed a close friend once said that he did nothing unintentionally.12

These images raise questions well worth considering, even if there are no correct answers – and even if there’s no certainty we even know the question being asked.

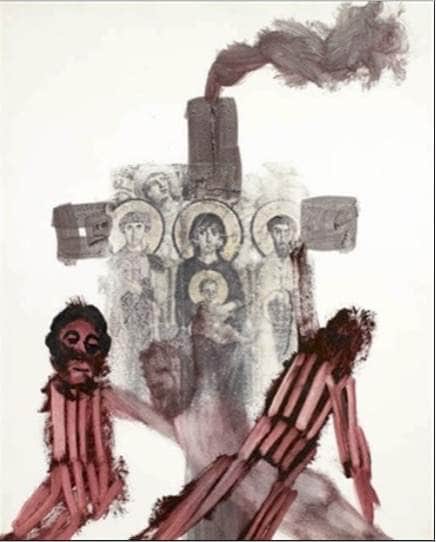

Sidney Nolan, “Auschwitz”, 1965

Some though are not so hard to fathom – what do we make of this powerful image? It’s from a series he painted after visiting Auschwitz. Two labourers, both distinct in the pyjama-type garb of the Auschwitz workers, lower a naked body from the cross which now carries a series of religious icons. One includes the Christ child. The cross doubles as a chimney. The smoke belches.

I find the symbolism of this painting particularly confronting. I’m not at all sure that Nolan isn’t suggesting this: that the historical Christ, the original Christ if you like, has been replaced over the course of 2000 years with religious iconography, plaster saints and baby Jesuses. And at what cost!

What might he think today?

Sidney Nolan, “Camp”, 1966-7

And this final compelling Auschwitz cross …

Wonderfull

Let’s move now to the Wonderfull – which by the way is not a typo.

Back in England from his first trip to the Continent he wrote this in a note to Bert Tucker.

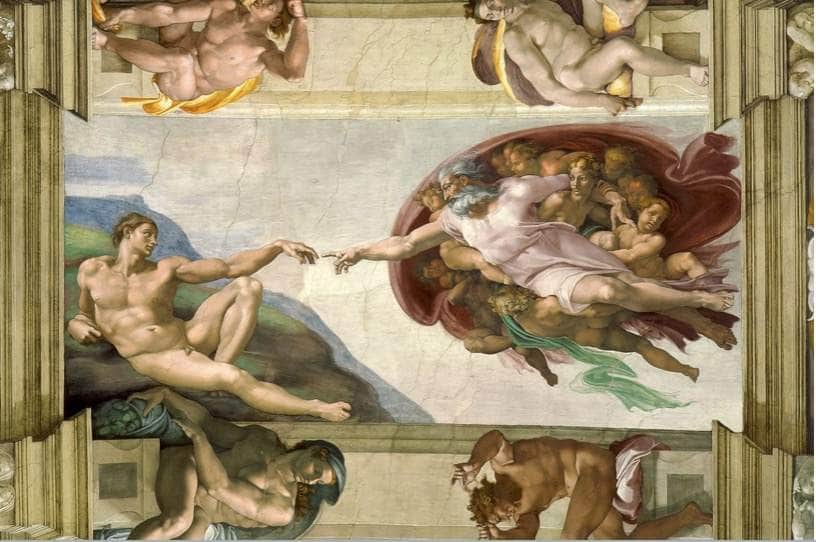

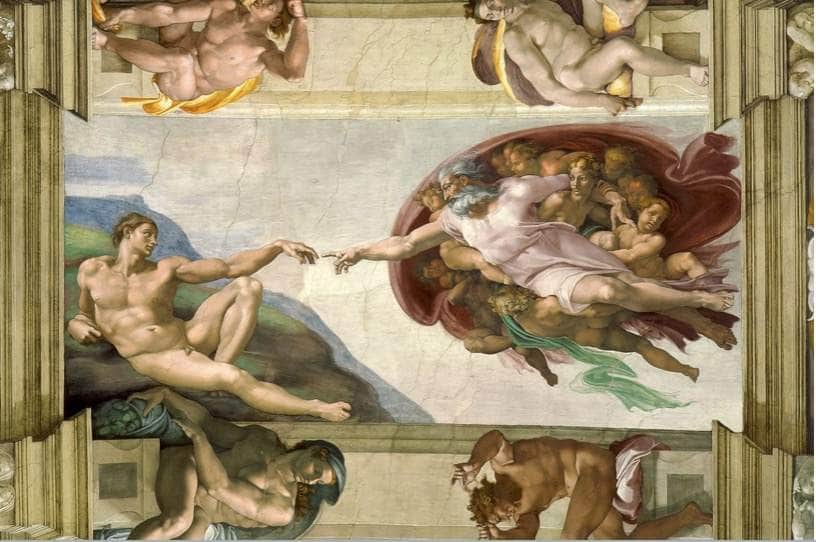

“Our trip in Europe forced a few rigorous conclusions on me. The outstanding one being that the painters who moved me most (El Greco and Giotto) seemed men primarily of faith. Presumably religious faith. The painting is wonderful in the sense that it is a painting of wonder. Differently from Michelangelo for instance, in the Sistine Chapel; which is certainly wonderful painting but by no means paintings of wonderment.”13

Michelangelo, ceiling of Sistine Chapel, Rome, 1508-1512

Here’s Michelangelo’s ‘wonderful’ painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – that’s wonderful with one ‘l’.

El Greco, “The Adoration of the Shepherds”, 1614, Prado Museum, Madrid

Here’s an El Greco painting of wonderment and ecstasy The Adoration of the Shepherds.

Giotto, “The Lamentation”, c. 1305, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

And here’s a Giotto painting – The Lamentation. It’s absolutely full of wonder – wonder-full, with two ‘l’s’ Look at those anguished angels – “God is dead” they lament.

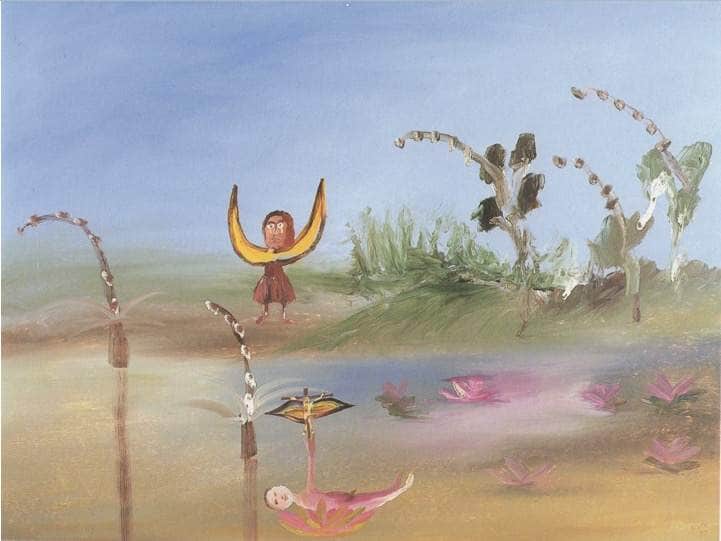

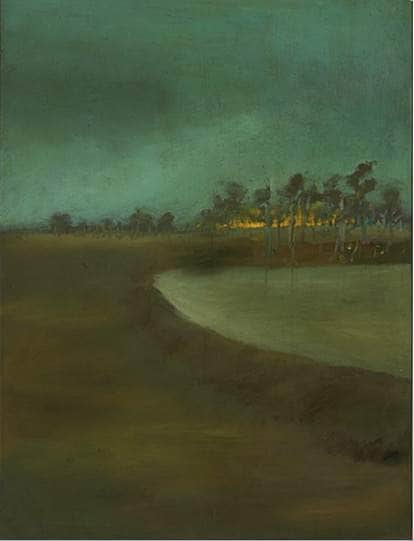

Sidney Nolan, “Religious Lake”, 1977

And this painting by Nolan when he was 60. Religious Lake I say is surely a painting of wonderment. One certainly wonders what it’s about. The girl with a set of wings, Is she an angel? What’s the story here? The waterlilies, one supporting .. is it a sprite? holding aloft a crucifix.

“I’d rather paint what I have to say than say what I have to say.” Indeed!

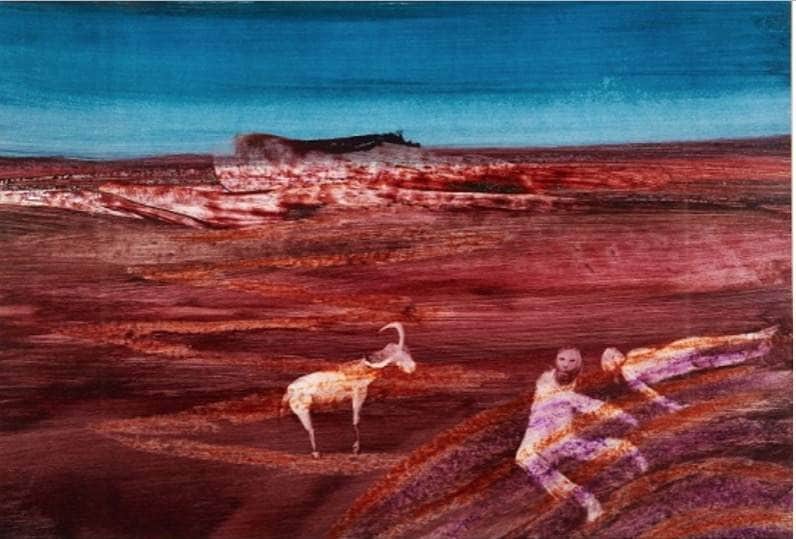

Sidney Nolan, “Abraham and Isaac”, 1967, collection Britten-Pears Foundation, Aldeburgh

This 1967 painting Abraham and Isaac tells the well known story of Abraham being asked by God to sacrifice his son. Nolan uses vivid colours, and with Uluru as a backdrop, we have a naked, bearded Abraham seated beside his son Isaac. Alongside is some animal, a goat perhaps. Is this the moment God declares that the sacrifice need not proceed?

What is Nolan saying here? He is certainly painting a divine landscape that, rather than being up there, is down here and out there.

I suspect Nolan was very familiar with the story of Abraham and Isaac, not only because of his knowledge of bible stories, but because of his fascination with the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard.

Nolan said he

“had 8 volumes of Kierkegaard. I bought the whole lot of them .… I went mad on Kierkegaard for 5 years. I think in the Army Kierkegaard sustained me.”14

Rather than coming to faith through reason, Kierkegaard advocated suspending reason to believe something that was above reason. In other words, taking a great leap of faith – and for Kierkegaard the story of Abraham and Isaac was the ultimate leap of faith.

Abraham and Isaac was not Nolan’s first narrative-style religious work. Back in 1950 when he returned from that first overseas visit, he painted a series of 8 or 9 of them over the Christmas/New Year period. He entered some in the then fledgeling competition for the Blake Prize in Religious Art.

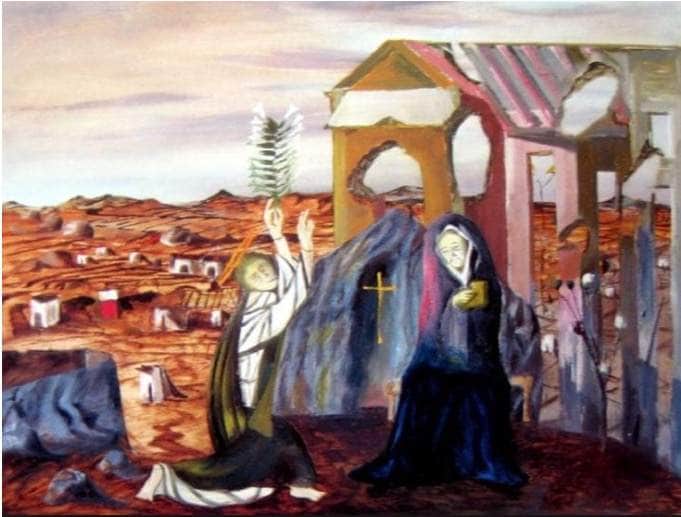

Sidney Nolan, “Annunciation”, 1951, private collection

This is Annunciation. Nolan is just back from seeing first hand the war-torn cities of Europe. What extra message might the Angel be bringing Mary, who’s kneeling beside a bombed out building? What message might Nolan be bringing us?

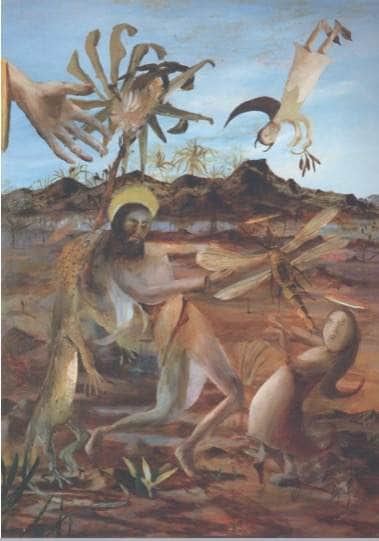

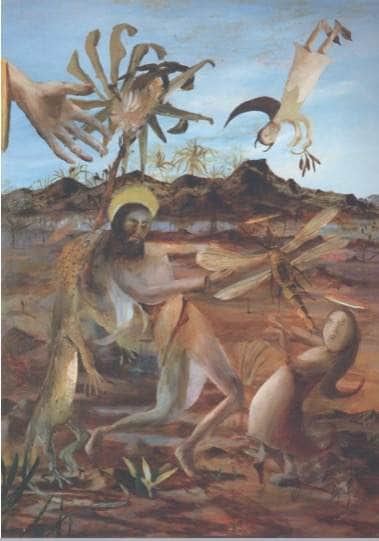

Sidney Nolan, “Temptation of St Anthony”, 1952, collection NGV

Here we have The Temptation of St Anthony, one of the Desert Fathers. Anthony was a Christian saint and hermit from the 3rd – 4th Century AD. He gave all his goods to the poor and retreated to the Egyptian desert where he led a monastic life. He experienced hallucinations and temptations, assaulting demons and erotic visions.

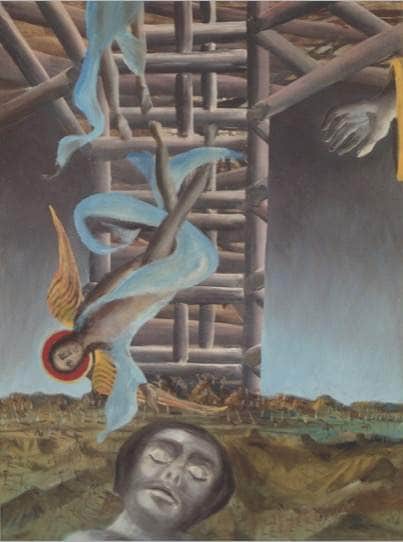

Here we see Nolan’s St Anthony, bearded and gaunt, dancing barefoot with a female spirit while attacked by a huge goanna and dragon-fly. A horned web-foot male spirit hangs upside-down in the sky. Will the hand of God we see up on the left save Anthony from the surreal horror of this nightmare?

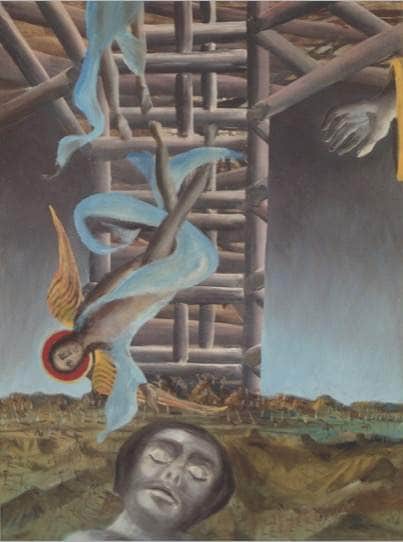

Sidney Nolan, “Dream of Jacob”, 1951, private collection

The story of the dream of Jacob needs little telling. Nolan’s notes for this quite surreal painting read:

“Almighty father above, Jacob sleeping at foot; (rock under head) bearded portrait, angel blessing sleeper before descending, another angel ascending.”15

Sidney Nolan, “St John in the desert”, 1951, collection Edith Cowan University, Perth

St John in the Desert shows John the Baptist in the wilderness – a central Australian wilderness complete with the facade of an Italian church. Cynthia Nolan wrote about it in her book Outback: “We also came to understand a sentence used by the explorer Leichhardt: ”This country is so old,” he wrote, “that as you look at it you seem to go back to Genesis.”16

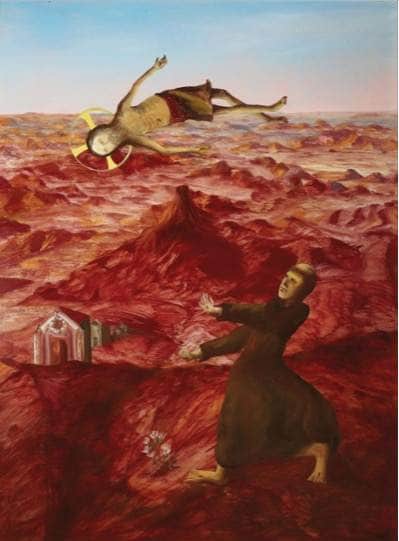

Sidney Nolan, “St Francis Receiving the Stigmati’, 1951, private collection, Sydney

Nolan was particularly struck by the story of St Francis of Assisi. Here’s his painting of St Francis Receiving the Stigmati – which is the manifestation in a human of the nail wounds in Christ’s hands and feet. Where the blood drips to the ground, Nolan paints flowers growing in an Australian desert.

Sidney Nolan, “Flight into Egypt”, 1951, private collection

Let’s look now at the painting which won Nolan 3rd place in the 1952 Blake Prize. The Flight into Egypt sees Mary and Joseph escaping from Herod with their child Jesus. Historically of course, they were actually refugees fleeing what today would be called ethnic cleansing. I wonder how Nolan would’ve painted it today, 70 years on.

Giotto, “The Flight into Egypt”, c. 1305, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

Here’s how Giotto painted the scene, 650 years before Nolan

Frank Hinder, “Flight into Egypt”, 1952, collection AGWA

and this is Frank Hinder’s version which won him the Blake Prize that same year.

Sidney Nolan, “Flight into Egypt”, 1951, private collection

What is it about these particular bible-based paintings of Nolan’s that’s so striking. Is it the upside down angels? the banana tree? the tent? the goanna? that whopping great dragon-fly? Is it the landscape?

The thing I find fascinating about these half dozen or so works is that they speak to me of an immanence. The God of the Old Testament, and of the New, is down here, not up there – Nolan’s God is out there amongst it all, not far away, not aloof. And most of all, the out there, the down here, is the Central Australian landscape. As Ludwig Leichhardt said, the country is so old, you go back to Genesis.

Nolan also made this connection. His biblical landscapes are no accident. This is from his diary on the voyage to England in 1949:

“In the Red Sea. Just passing Mt Sinai. The whole country strangely related to Central Australia. In fact our period in Australia now feels like an apprenticeship.”17

And he wrote this in his diary in 1952:

“what search is at the back of my present series of religious paintings? Does one conceive of Jesus as the ultimate hero? This is an attractive proposition for painting but seems a travesty as far as faith is concerned.”18

The curator of the NGV exhibition Images of Religion in Australian Art wrote this about these religious paintings: “Nolan created luminous, dreamlike, mystical images. To enter these religious paintings demands a leap into the unknown, a forsaking of the familiar territory so often traversed by other painters, a suspension of credibility that is beyond the kind of rationality so valued by traditional theology.”19

Our Saviour

I’ll consider here whether Nolan painted Saviour-like images. But first, let’s look again at that crucifix Nolan had in his study.

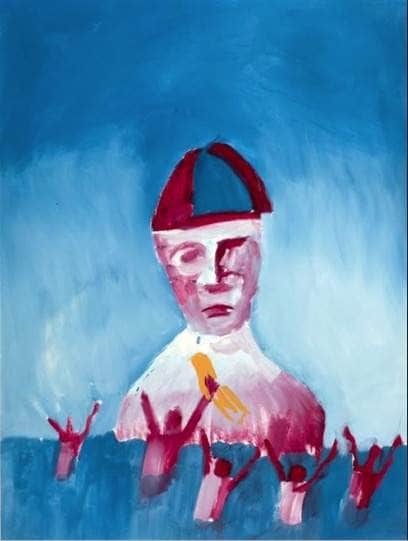

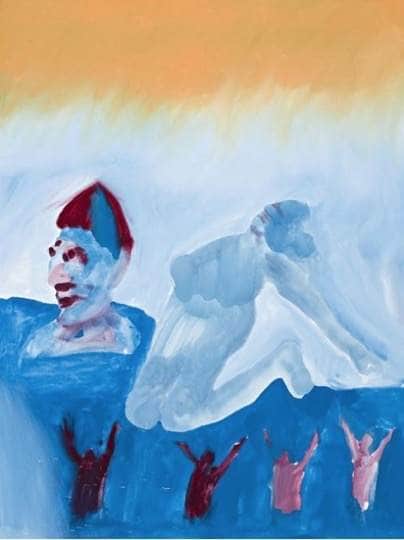

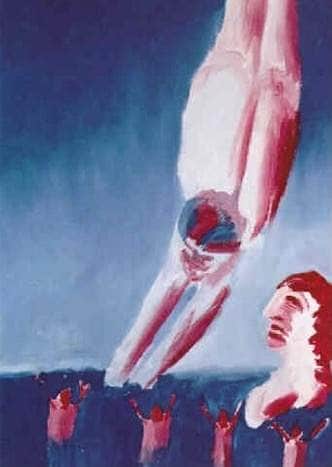

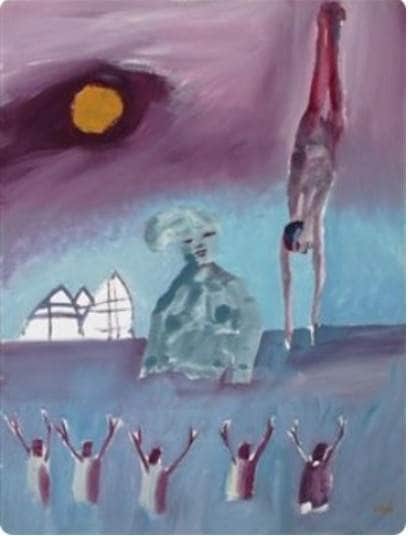

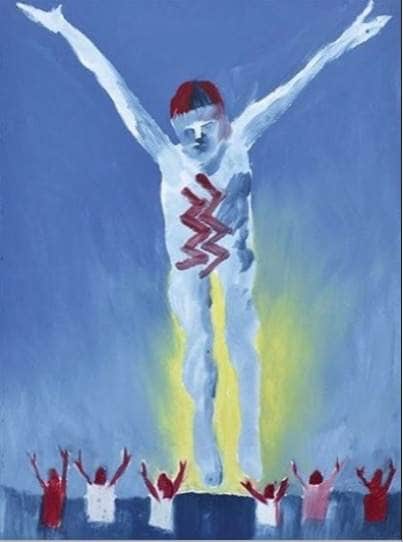

Sidney Nolan, “The Lifesaver”, 1975

This painting,

Sidney Nolan, “Bather”, 1975

and this one, are from the Bathers series he did in the mid 1970s. All of them have a bunch of swimmers and a lifesaver. And you are probably wondering

what they have to do with this crucifix.

Well you can see it here. Nolan is experimenting. He’s juxtaposing the crucifix against the Bather paintings and taking photos. But look at the arms of the Christ figure – now look at the arms of the bathers! And what about that lifesaver – is he actually their savour?

Something here rings a bell.

… another experimental photo he took.20

Now let’s look with new eyes at more in the Bathers series.

Sidney Nolan, “Australian Lifesaver”, 1975

Sidney Nolan, “Diving Bather”, 1975

And the bathers arms, are they raised in praise and supplication?

Sidney Nolan, “Bathers, St Kilda”, 1975

It’s obvious they’ve been painted quickly … they’re rather repetitive, and it’s easy to see why his total output is estimated to be in the tens of thousands. He’s talked about this aspect of his practice:

“I’m very interested, in fact, compelled and dedicated to transmitting emotions and I care for very little else. I care for that process so much that I’m prepared to belt the paint across the canvas much faster than it should be belted. I don’t care – so long as can get the emotional communication I will sacrifice everything to it – and that I’ve done.”21

Sidney Nolan, “Bather”, 1975

I find this image particularly fascinating. What’s been painted here by this chap who paints what he has to say?

Does it allude to the Ascension? It certainly reminds me of those old pictures of the Ascension with the crowd below, arms raised, and Christ heading heavenwards in clouds of glory. That photo of Nolan’s with his crucifix superimposed on the lifesaver painting, does it suggest the image of a Saviour, is the lifesaver a Christ-like figure?

“He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God”

The Hand of God

Perhaps we should take a look at how Nolan imagines the hand of God.

Michelangelo, ceiling of Sistine Chapel, Rome, 1508-1512

Here first, is Michelangelo’s image again.

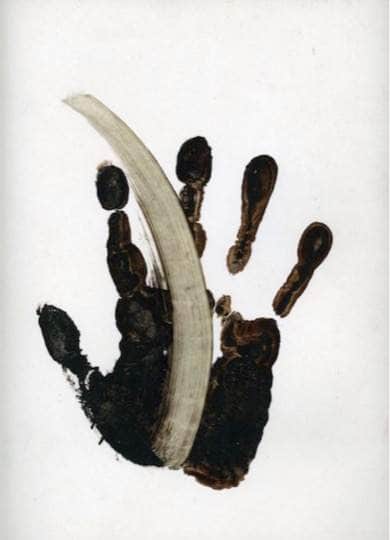

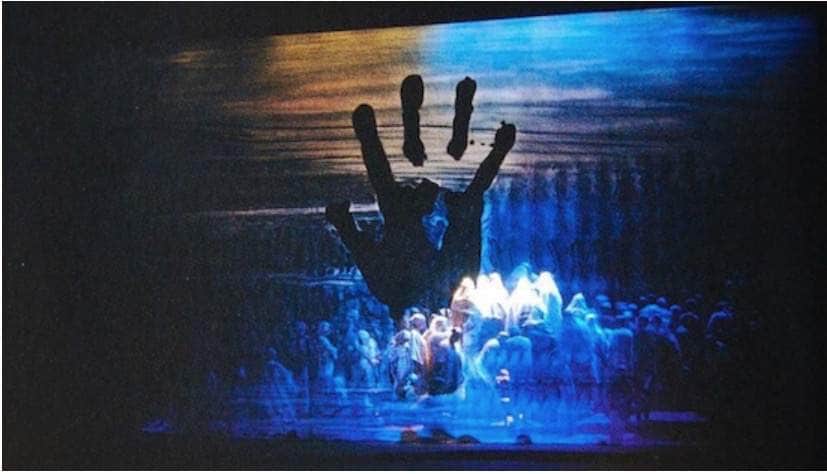

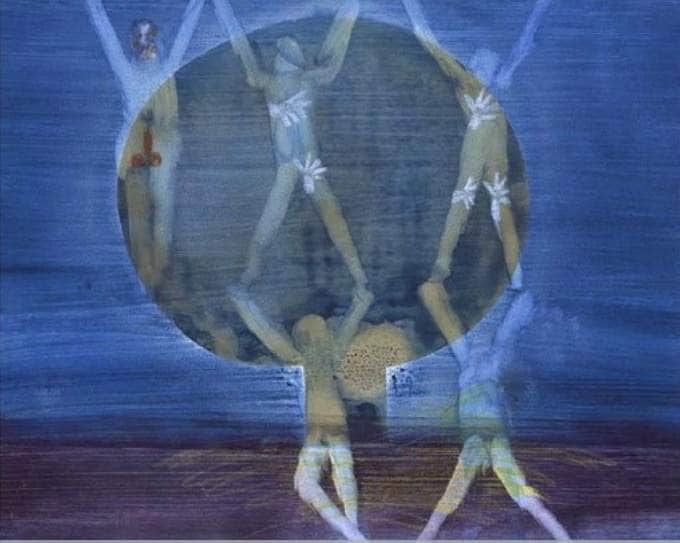

Sidney Nolan, Study for Samson et Dalila, 1981

And here’s Nolan’s.

In 1981 he designed the sets for the Covent Garden production of the Saint-Saëns opera Samson and Delilah which was directed by the young Australian Elijah Moshinsky. Last year Moshinsky recalled how Nolan created this image.

“ ‘What is that first scene about?’ Sidney kept enquiring. “Not the action of the scene but its nub, its inner core.” Eventually he forced me to find it. It was about God. The Israelites feeling lost and abandoned by Jehovah. This idea absolutely hit him with force. He said ‘What if we do it from God’s point of view?’ He then painted, very quickly using vivid dyes, a blue background and on it he put the imprint of his own hand painted black.

“The effect in performance would be that we saw the Israelites obscurely in white and blue sections of the stage picture, and the imprint of the black hand would act as a void through which we could see the disposed Hebrews clearly. This symbol, he explained to me, came to him from aboriginal rock paintings. It was, he said, the first expression of Man’s self awareness. For Nolan, it was a symbol of creativity in man, The Hand of God.”22

And we’ve seen other paintings which feature the hand of God …

Sidney Nolan, “Temptation of St Anthony”, 1952, collection NGV

here to save St Anthony from more temptation …

Sidney Nolan, “Dream of Jacob”, 1951, private collection

and here, steadying the ladder for Jacob’s angels.

But we haven’t seen this hand of God before …

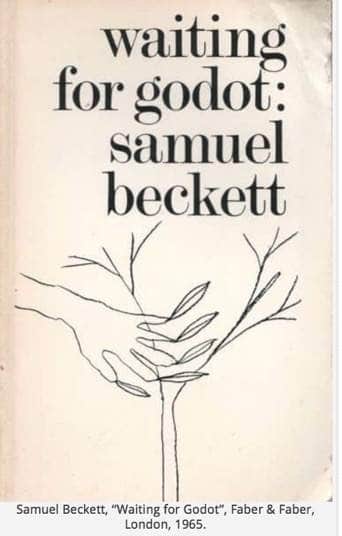

In the mid 1960s Nolan designed this cover for a new printing of Samuel Beckett’s famous play Waiting for Godot.

Why is this the hand of God? Well, I’m not entirely sure that it is, but here’s one thought – and I don’t know if it comes from Charlie Brown or from Linus.

In Waiting for Godot, nothing much appears to happen. The same characters are waiting for the mysterious Mr Godot at the beginning and at the end. Are they transformed in the process? I’m not sure. But something else certainly is. The stage directions for Act 1 are simple: “A country road. A tree.” Beckett’s changed this for Act 2: “The tree has four or five leaves”. That’s transformative.

Who knows if this was Nolan’s intention, but here I can imagine a conflation of that take of mine on the Divine in Waiting for Godot, with an analogy for the Divine used by a British-born Benedictine monk Bede Griffiths who was quite a well known public figure when Nolan did this cover.

Griffiths said: “I often use the illustration of the fingers and the palm of the hand. Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity are all separate in one sense. But as you move toward the source in any tradition, the interrelatedness begins to grow. As one might say, we meet in the cave of the heart. When we arrive in the centre, we realise the underlying unity behind the traditions.”23

I wonder has Nolan placed Beckett’s tree leaves on Bede Griffiths’ hand of God? Or am I just imagining it? And if I am, why not?

The Garden of Eden

And so to the Garden of Eden.

We’ve already seen a few of these. Here

and here. But there are some more.

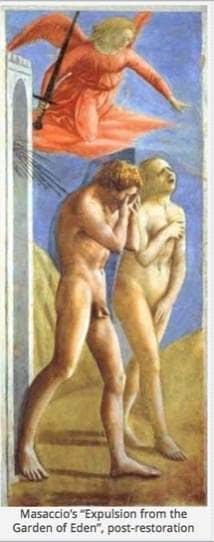

This though is not Nolan – rather this expulsion from the Garden of Eden is from the 15th century; by Mossacio, in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence. Nolan most certainly saw it, and he borrowed its likeness for this later painting

of Mrs Fraser and convict, which we see here on the cover of Patrick White’s novel Fringe of Leaves.

Nolan said a few things about Paradise over the years:

“We are now finding that Australia is a kind of Paradise, something we didn’t realise when we were young. This dry, old place, a little boring, perhaps, is a kind of untouched Garden of Eden”24

and this:

“The thing you come to realise is that nothing is fixed – that everything keeps being transformed – and you have to sense where Paradise is in the process. …. That is what eternity is – a total rolling series of transformations. …. The thing is to try and find a Paradise in the process of evolving all the time.”25

Not bad words for someone who preferred to paint what he had to say!

And finally, on a much lighter note

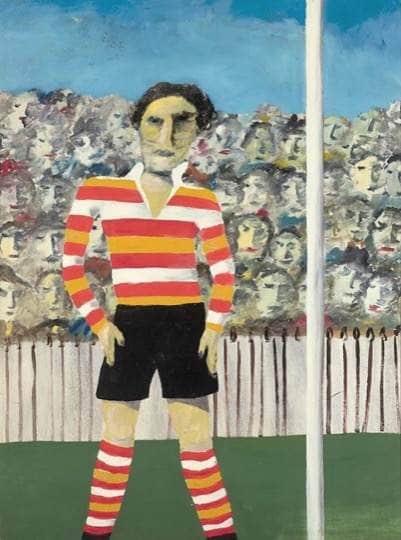

Sidney Nolan, “Footballer”, 1945, collection NGV

This surely is the most sacred of Nolan’s religious images – his 1945 painting Footballer – because everyone knows Aussie Rules is the Melbourne religion!

So with St Kilda full-forward Bill Mohr alert and waiting, this is a good time for everyone to stretch their legs for a bit. Play will recommence in 5 minutes.

<< HALF TIME >>

We’ve seen quite a few images that touch on the Religious in Nolan’s paintings. What can be said about the Religious in Nolan’s person?

Well, being born in 1917 he was a child of the 1920s. That was a time when most people had connection with a church in one way or another. I’ve not been able to discover whether his family were church-goers, whether there may have been family prayers, bible-reading, the saying of grace with meals etc.

I asked his daughter and she said he’d never talked about it with her. His biography mentions that he attended Youth Group meetings at the St Kilda Baptist Church. All in all, it seems reasonable to assume that he did grow up with some degree of religious familiarity, as most kids of his time would have. He’s more or less said himself that he devoured the Bible.

He was certainly nothing if not ecumenical in his religious preferences. Youth group meetings with the Baptists, his first wedding Swedish Lutheran, his second Presbyterian, a London Registry Office for the third, and his funeral and memorial services staunchly Anglican: St Martin-in-the-Fields and St James’s, Piccadilly no less.

Whether he gained knowledge from regular attendance at more conventional religious gatherings and services I’m less sure. In fact I doubt it. But I rather suspect he most likely could have taught most of us a thing or two.

Let’s look at what others have said.

Back in 1964 a leading British arts commentator said “He is extremely well-read, deeply concerned with spiritual and philosophical issues” and concluded “Whilst not himself religious in any formal sense, Nolan is ever-conscious of the spiritual or communal impulse necessary to great art. When this is absent he feels art is in decay.”26

His daughter told me “Sid reflected on life in a spiritual way and expressed that in his paintings, writing and general conversation – deceptively flippant though the last often was.”27

Finally let’s hear from the man himself. Again we see that he speaks very clearly for someone who would rather paint what he has to say than say it.

Not quite 50, he said this:

“I would say I would like to be a religious person. Perhaps I am. But I feel we 20th century ones are midway between two religions. The first is Christianity which has been tried and found wanting. The second is yet to come. God only knows what it might be”28

Ten years later he was still looking to the future:

“I now realise that there is a time limit for what I want to do. There are areas, spiritual as well as technical, which I haven’t explored. What an artist really wants is to say something which, one day, out of contemporary contexts, will mean something important, will be sure of survival. This is quite different from momentary success or fulfilling current demands. It is a deeper need, more like the maternal feeling for children. And because you don’t know when that might occur, you have to chase it incessantly.”29

I’ve wondered whether Nolan knew this maxim by Vasili Rozanov: “All religions will pass, but this will remain: simply sitting in a chair and looking into the distance.”30 It was certainly known to Richard Holloway, one time Bishop of Edinburgh and Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church. Like Nolan, he had some difficulty holding fast to both the Divine and the Religious. He called his book of disillusion and loss of faith Looking in the Distance.

I can’t find anything linking Nolan to the maxim. Except, perhaps indirectly,

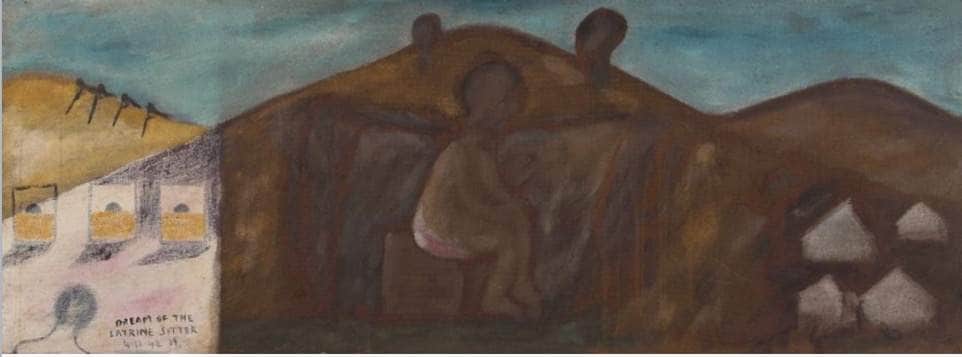

Sidney Nolan, “Dream of the Latrine Sitter”, 1942, collection AWM

this one painting Dream of the Latrine Sitter. It was painted several months after Nolan’s war began and he was guarding a food supply reserve at Dimboola in the Wimmera. He had lots of spare time. He sits and looks and thinks. Little wonder perhaps that Nolan’s request to be appointed an official war artist fell on deaf ears!

Apart from the obvious, what do we see here? Is that a golden Calvary on the left? Four crosses above the targets at the rifle range?

THE SUBLIME

Returning for a minute to Vasili Rozanov. His notion of “simply sitting on a chair and looking into the distance” is one way of thinking what the Sublime is about.

The Romantic Sublime

The Romantic Sublime refers to the notion that the world, that nature – by virtue of its power, its immensity, its beauty, at times its terror – can inspire awe and even dread. By way of comparison, human existence is transient and fleeting.

In the Sublime can be found one way of directly confronting God’s presence in the world – the Divine in the Sublime.

Although an ancient idea, this notion of the Sublime took particular hold towards the end of the 18th and into the 19th century. It was almost an antidote if you like, to the Industrial Revolution which seemed to postulate, to even prove, that man alone was in control of his destiny.

The work of many artists embraced this theme, and none more so than the German painter Casper David Friedrich

Friedrich, “The Monk by the Sea”, 1808-1810, collection Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

whose famous work Monk by the Sea we have here. A wintery watery landscape shows a raw and powerful side to nature of a kind never painted before. A vast sky takes up most of the canvas. It looks cold yet is clear at the top, but as we move lower it becomes much darker, more menacing, until the ocean below,

Friedrich, “The Monk by the Sea”, (detail)

freezing cold and almost black with rolling swells and white capped waves, confronts the solitary figure of a monk standing alone on the cold winter dunes – his tiny figure just visible beneath the horizon line.

In 1988 Nolan spoke of his feeling for the Kimberley and said this:

“… it’s the same feeling you get with Friedrich and his famous picture Monk by the Sea.. This shows a single figure of a man looking out by the sea; he’s seen from behind

Sidney Nolan, “Ned Kelly”, 1946, collection NGA

That’s the same as Ned Kelly in that key painting where he’s on the horse looking out into nothing.”31

The Celestial Sublime

Our notion of the Celestial Sublime took a giant leap when Neil Armstrong spoke his famous words as he stepped onto the moon, and Buzz Aldrin on the journey back to Earth recited from Psalm 8, ”When I consider Your heavens, the works of Your fingers, the moon and stars, which You have ordained, what is man that You are mindful of him, and the son of man that You visited him?”

One of Nolan’s most iconic images, and one he used many times over many years, is of the moon.

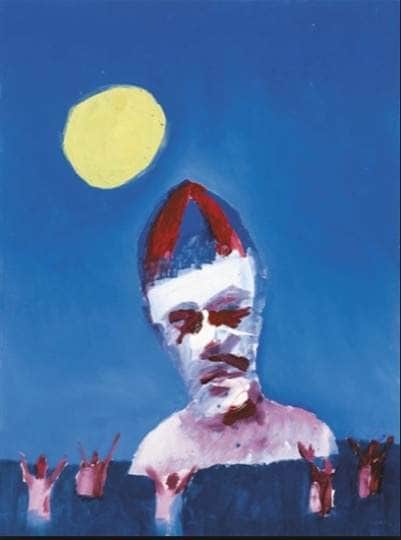

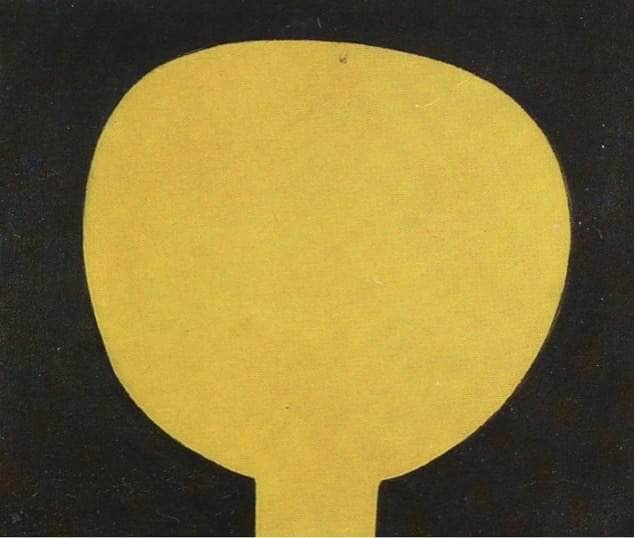

Sidney Nolan, “Moonboy” or “Boy and Moon”, 1939-1940, collection NGA

Do you recall the photo of a bare-chested Nolan at the Heide Christmas table in 1946. Remember the chap standing up holding a little dog? Well this is him. John Sinclair.

He and Nolan had been mates for years and one night in 1939 the two of them were down on the esplanade at St Kilda chatting on a park bench when Nolan was struck by the bright golden full moon rising. It appeared to sit on Sinclair’s shoulders and swallowed his head. He painted it soon after, inscribed it “Portrait of John Sinclair at St Kilda”, and called it Moonboy.

Much has been said by many over the years about this work, particularly that it led to Nolan’s Ned Kelly mask. To me it seems a classic image of a celestial sublimity – whether it’s Sinclair (not Sinclair really, but rather it could be you, me, Everyman) sitting on a chair and looking into the distance; or whether it’s the painter looking from the distance beyond the moon towards us, the viewer.

Narelle Jubelin, “Moonboy”, 2012, temporary installation on Heide I roof

During the war Nolan painted it on the roof at Heide and the military authorities insisted it be removed in case enemy aircraft used it as a sighter! Here we see Moonboy recreated on the Heide roof a few years ago.

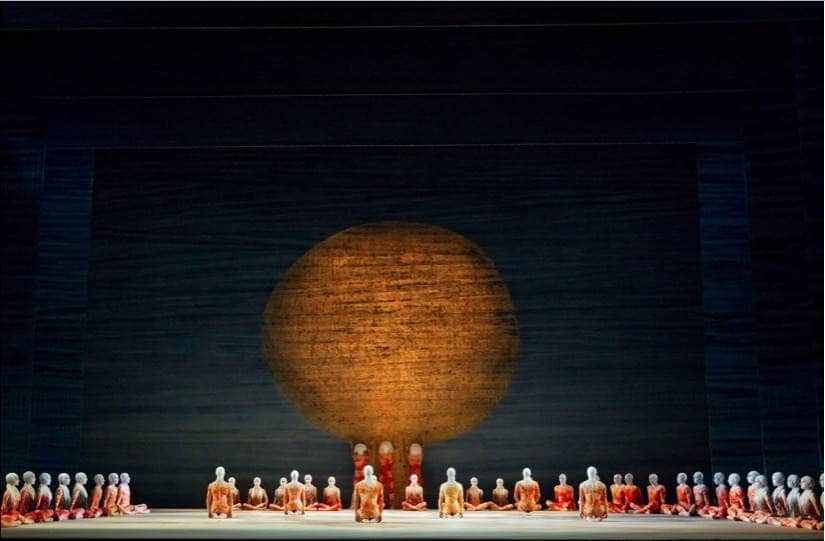

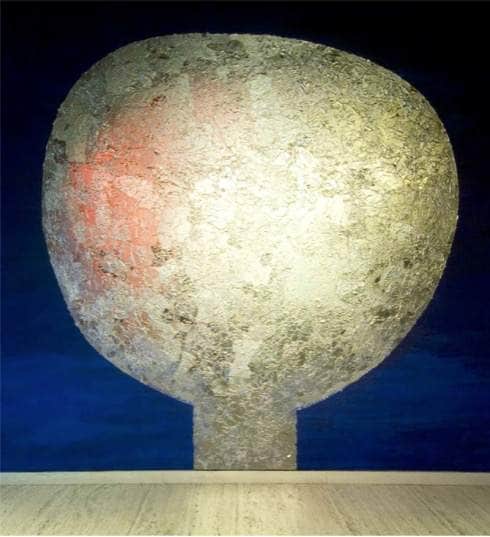

In 1965 Nolan used the Moonboy motif in his designs for the Royal Ballet production of Stravinsky’s Rite of spring at Covent Garden.

It was set, as you see here, in Australia

a merging of the Celestial and the Centralian Sublime perhaps.

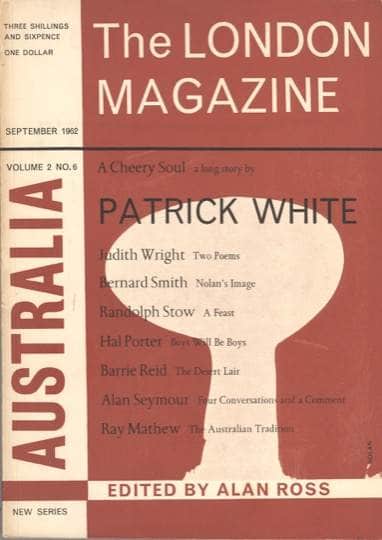

In 1962 for the cover of The London Magazine, he’d morphed Moonboy into an ominous mushroom-shaped nuclear cloud. Ominous, and prescient – it was only a few weeks before the Cuban missile crisis brought the world to a halt.

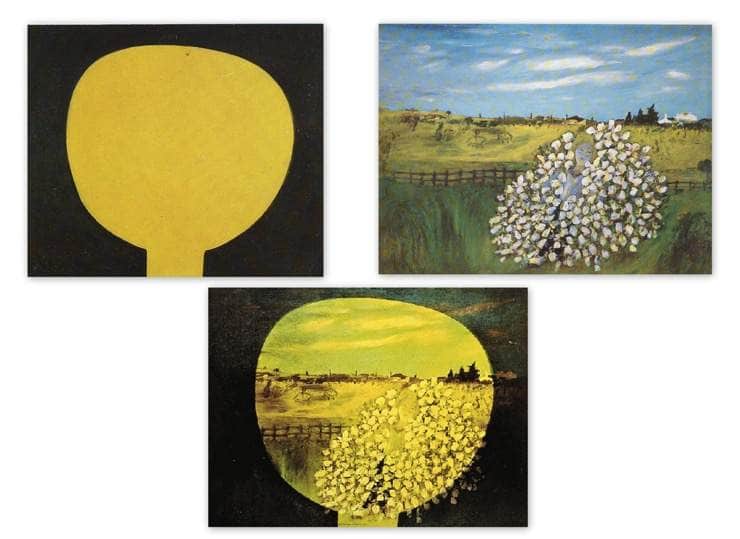

Sidney Nolan: (top L) “Moonboy”, 1939-40, collection NGA; (top R) “Rosa Mutabilis”, 1945, collection Heide MOMA; (bottom) “Homage au Prix Nobel”, 1973, private collection

In 1973 Nolan even linked Moonboy with the Nobel Prize. That was the year Patrick White won the Nobel Prize for Literature and not wishing to travel to Stockholm, he asked that his good friend Sidney Nolan should receive it on his behalf. That year a Swedish gallerist, aware that 33 countries had so far produced a Nobel Laureate, arranged for an artist from each country to produce a work on paper dedicated to the Nobel Prize.32 Nolan was chosen to represent Australia. We see here how he combined Moonboy with another early painting Rosa Mutabilis to produce his Homage au Prix Nobel.

Sidney Nolan, “The galaxy”, 1957-58, collection AGNSW

This 1957 Nolan image of the celestial Sublime is called The Galaxy. His granddaughter Lizzie Langslow chose it for her contribution to last years Centenary listing of the Nolan 100.

She wrote this: “Sid was my grandfather and in thinking about a favourite picture, this one came to mind. It makes me think about the afterlife and whether we might all turn to light. The figures in the painting drift together through inky space, like Great ancestors from aboriginal cosmology. It gives a calm and gentle feeling that there is company in the void. It reminds me of Sid’s other paintings of people fading back into landscapes or water.

Galaxy also pays homage to fallen soldiers. Sid lost his young brother Raymond in the war. In other paintings, Sid represents Raymond with figures at rest. Sid wrote to mum once that ‘painting is only a part of life, but nevertheless can bring about the kind of feeling you get when talking closely to someone without any hindrance to understanding.’

For me Sid’s Galaxy painting is like that. A kind of map left behind to locate Sid and the people he loved.”33

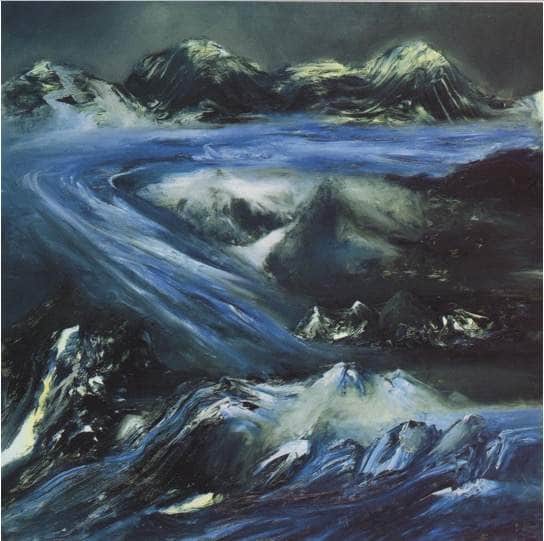

The Antarctic Sublime

Nolan experienced the Antarctic Sublime first hand in 1964. He’d never seen anything like it. His companion was Alan Moorehead who said: “There are great rewards for anyone who penetrates into this wilderness, not only in the things he sees, which are like nothing else on this earth, but also in the sense of freedom and clarity he feels in simply being there at all.”34

Sidney Nolan, “Explorer”, 1964, private collection

“These are regions where it is not normal that human beings should ever be. The polar explorer is an embattled figure with staring, goggled eyes and a swirl of protective covering around his head and body.”35

It’s in an Antarctic context of images like this that a poem of Nolan’s speaks of “sweet heaven”:

“the Antarctic mist

on the many fleeces,

sweet heaven in pieces”36

Sidney Nolan, “Explorers”, 1964, private collection

One commentator said: “With ice-rimmed eyes and beards stiff with frost, Explorer peers into the white nothingness …

Sidney Nolan, “Antarctica”, 1964, private collection

… as though into a fish bowl.”37

Sidney Nolan, “Glacier”, 1964, private collection

And from Alan Moorehead again: “In the Antarctic and in much of Central Australia one finds the similarity of great extremes. Both are dry deserts, the one of ice and the other of rock and sand … and the occasional storms rising up to the pitch of hurricanes, leave behind them an absolute silence and stillness.”38

Sidney Nolan, “Frozen Sea”, 1964, private collection

This from Jack Lynn, a close friend of Nolan’s: “Icescapes without a sign of life stretch away with diminishing repetitiveness, like the brown Australian interiors done a decade ago.”39

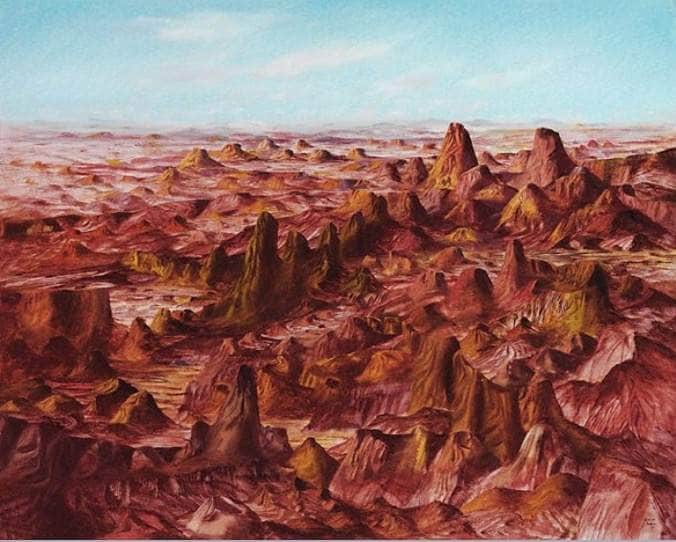

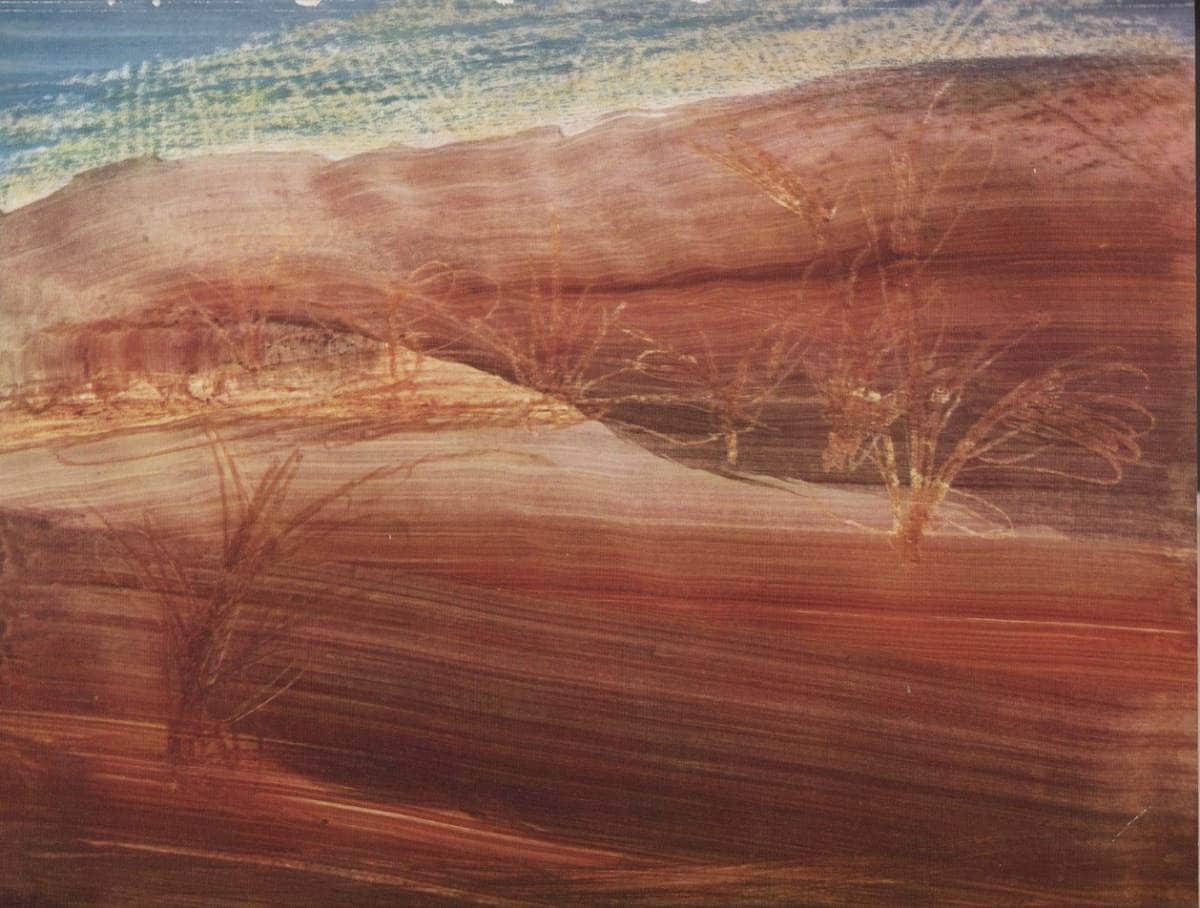

The Centralian Sublime

Let’s now look at some of those ‘brown Australian interiors’ in the Centralian Sublime.

Sidney Nolan, “Central Australia”, 1950, collection ACTMaG

Sidney Nolan, “Central Australia”, 1950, collection AGNSW

Sidney Nolan, “Central Australia”, 1949, collection AGNSW

Hardly any words are needed from me, but Nolan was pretty clear on what it meant for him:

“The implacable, beautiful landscape … How can one put it? It’s God’s gift to the world. In Australia there’s a wonderful light that shines upon it and makes it ethereal, but also makes it impossible … a wasteland.”40

Sidney Nolan, “Inland Australia”, 1950, collection Tate

This is Nolan talking about these works 30 years after he painted them:

“I wanted to deal ironically with the cliché of the “dead heart” … I wanted to paint the great purity and implacability of the landscape. I wanted a visual form of the “otherness” – of the thing not seen.”41

150 years ago, explorers finally stepped into this paradise, cattle would follow …

The Colonial Sublime

and there was established a new sort of Sublime – a Colonial Sublime.

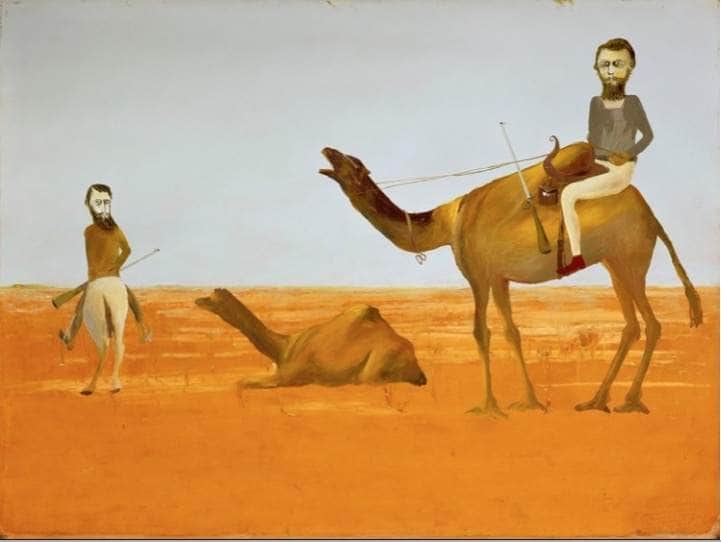

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills Expedition” 1948, collection ACTMaG

Here in this earliest work, we see the explorers Burke and Wills

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills leaving Melbourne”, 1950, private collection

and here they are leaving Melbourne and looking out at us. Nolan’s positioned us, the viewers, out in the vast unknown.

What is the man who paints what he has to say, telling us here?

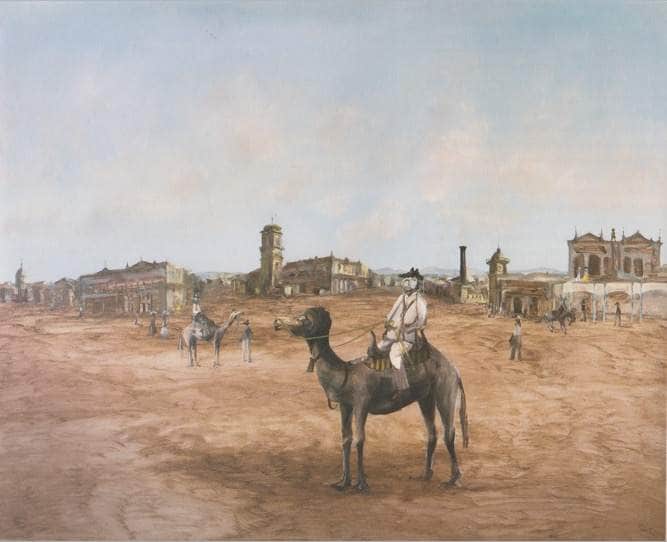

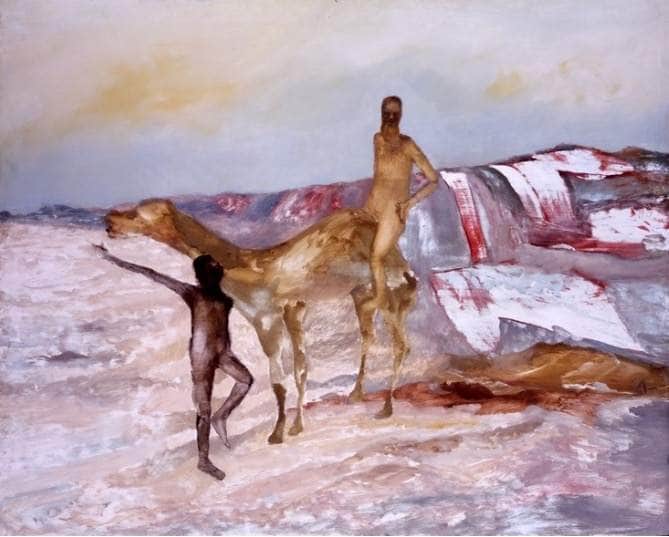

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills at the Gulf”, 1961, collection NGV

or here, painted 20 years later, the explorers now naked and vulnerable under a brooding, menacing sky?

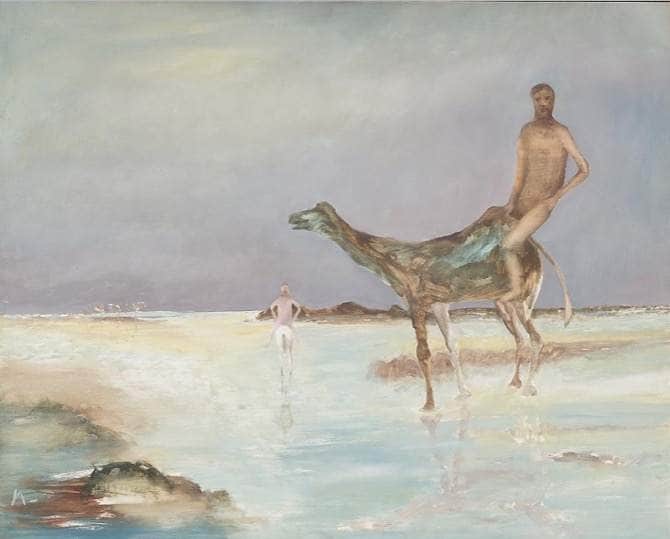

Sidney Nolan, “Burke and Wills expedition”, 1962, private collection

or here, where an Aborigine in characteristic one legged stance, actually points the way to salvation, but is ignored by the bearded, naked Burke who takes little notice and still gazes out towards us. Are we perhaps his fellow travellers in the unknown? Is Nolan telling us something here?

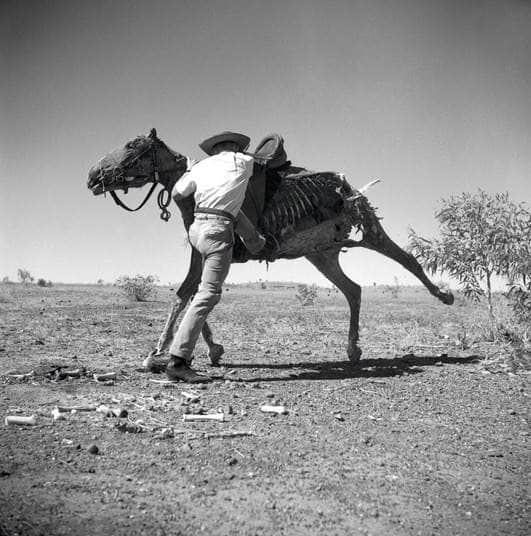

In 1951 Nolan was commissioned by the Brisbane Courier Mail to produce a series of paintings that would depict the extreme drought raging across inland Australia.

First he took a series of remarkable camera images – a photographic evocation of the Sublime – a colonial Sublime – like no other. These photos, even with people and animal carcasses centermost, have that Sublime backdrop best characterised by the single word ‘dread’. They included photographs of a first people whom Nolan realised had very much become second.

This photograph of Brian the Stockman at Wave Hill Station Mounting a Dead Horse was chosen by Damian Smith, one of the contributors to last years Nolan 100 – a Centenary tribute. He said this: “Of all of Nolan’s vast outpouring, this photograph remains, in my mind, a work of originality, inventiveness, forward thinking and compositional panache. It is as artworks should be, utterly of its time and utterly timeless.”42

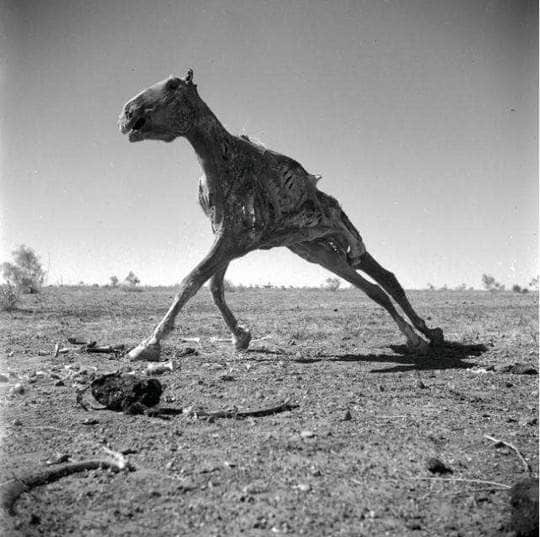

That drought had been long and hard. It laid waste to the inland, parched the soil, withered the vegetation. Horses and cattle alike died of thirst. Their carcasses lay bleached and desiccated under the sun.

As we scroll through, consider just what these carcasses speak of.

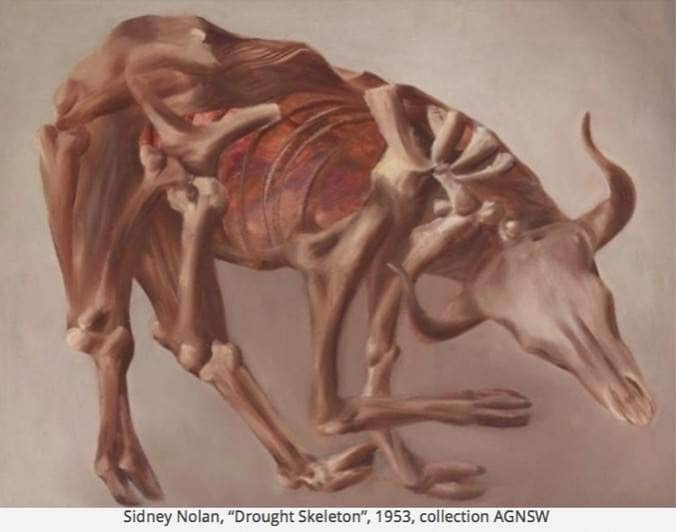

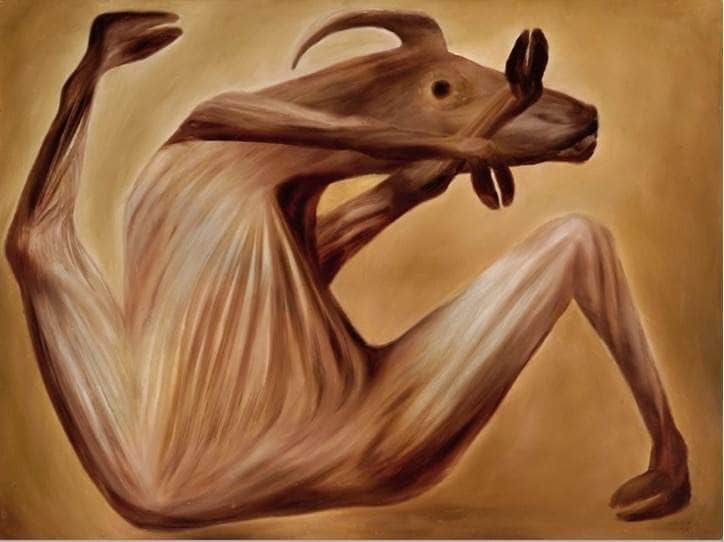

From these photos, Nolan painted a series of works that became known as the Carcass paintings.

Here’s one ..

Sidney Nolan, “Carcass”, 1953, collection CMAG

and here’s a second.

Did Nolan perhaps see these withered horse and cattle carcasses as a substitute, a metaphor perhaps, for massacred Aboriginal bodies – not left beneath the withering sun to desiccate, but burned to remove evidence of slaughter?

Who knows, but once having made that connection, I find it difficult to look on these images of Nolan’s in the same way.

“I’d rather paint what I have to say.”

Now, we’ll turn more directly to the Divine in Nolan’s work.

THE DIVINE

But seeking the Divine explicitly presents a problem. How does one portray what for the Theist is beyond all knowing, and what for the Athiest is non-existent?

The approach I’ve adopted is based on Genesis: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him”

The Image of God is a well known expression – imago Dei in latin. The trouble with the imago Dei for this exercise is that it’s a theological concept – not an artistic one. The proposition underlying the imago Dei is fairly easily expressed: Since humanity is made in God’s image and likeness, then we should all recognise a Divine in others, without exception, and honour and respect it.

So what if, in an artistic sense, we were to take the imago Dei literally?

What if an artist were to express his or her notion of the Divine by portraying the treatment of certain people, or classes of people, who in line with Genesis, are the image of God.

What if we were to examine paintings with a view to finding a Divinity in the work’s portrayal of other humans – people who, by their very creation, are made in the image of the Divine.

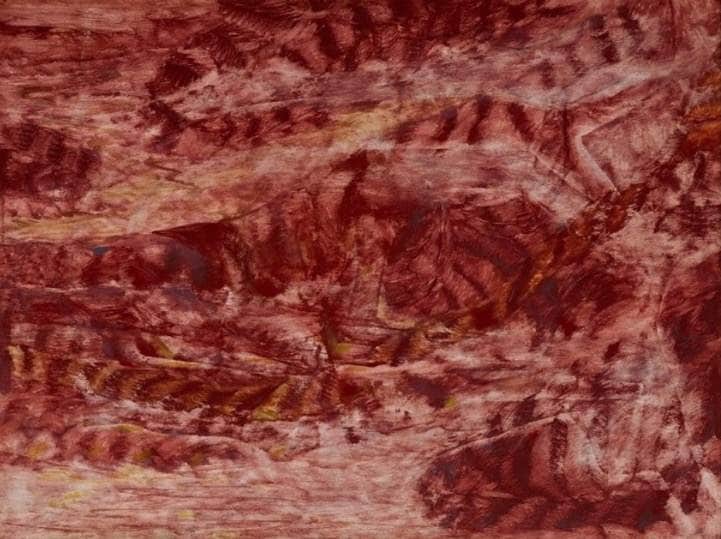

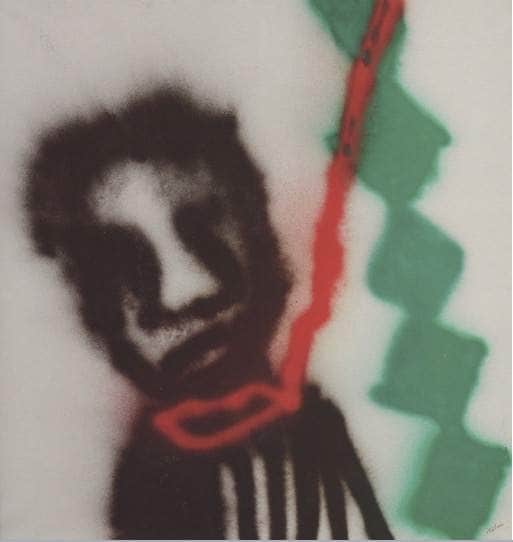

Sidney Nolan, Untitled, 1987, collection Sidney Nolan Trust

Something like this. This painting by Nolan is one of the most striking images in a series of huge spray paintings he did in the late 1980s on the theme of Aboriginal deaths in custody.

Does this painting by Nolan show the Divine in the dying faces of Aborigines? He said he’d rather paint what he had to say, than say what he had to say. What’s he saying here?

The Divine in First Peoples

His visit to the Outback in 1949 enlivened his interest and tweaked his conscience. So let’s look at some Nolan paintings that feature Aborigines.

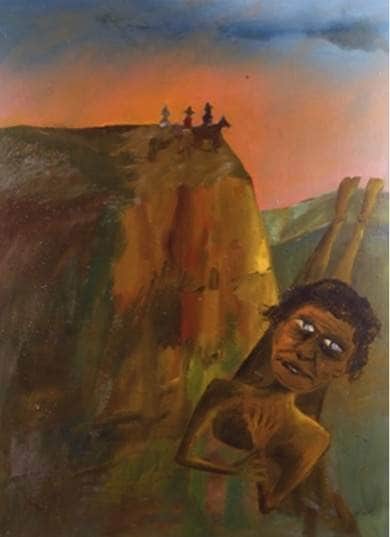

Sidney Nolan, “Aboriginal hunt”, 1947, private collection

He was alert to their plight before he visited the Outback. This painting is called Aboriginal Hunt and was done in 1947 when he was 30. We see a group of mounted men above a cliff top, and an aboriginal youth falling, almost floating down. Nolan said it related to an incident in Tasmania.

Sidney Nolan, “Aboriginal hunt”, 1988, private collection

This later work is from the late 1980s. It’s also called Aboriginal Hunt and also relates to Tasmania.

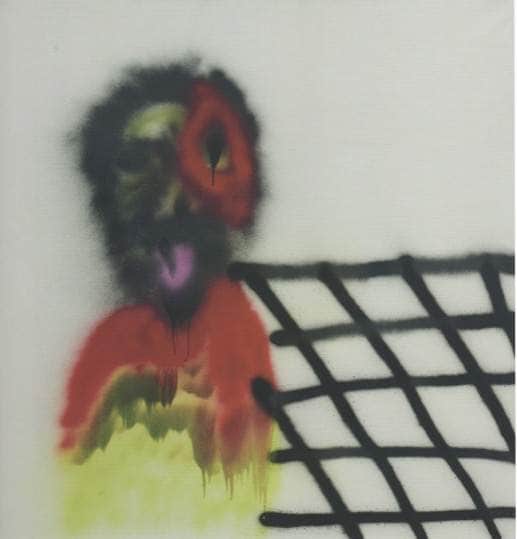

Sidney Nolan, Untitled, 1987, collection Sidney Nolan Trust

I’ll let these images proceed.

Sidney Nolan, Untitled, 1987, collection Sidney Nolan Trust

Listen to this. Sidney Nolan talking in the late 1980s about the plight of Aborigines.

“… the Aborigines actually had a fantastic culture. A very very beautiful people and a wonderful synthesis of another world and this world. … it is one of the most fantastic cultures that ever existed, including the Egyptians and everything else. It’s gone on for 40,000 years.”43

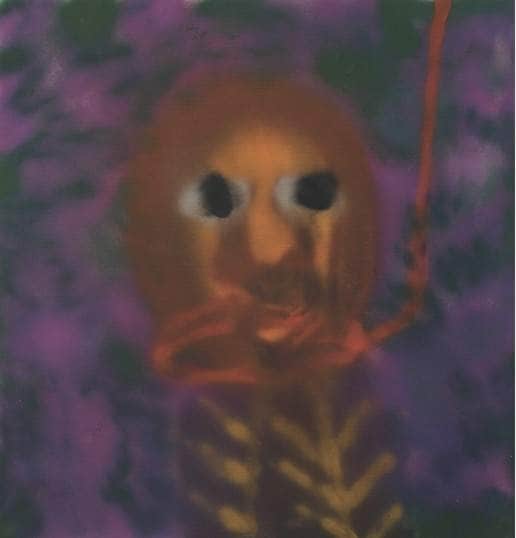

Sidney Nolan, Untitled, 1987, collection Sidney Nolan Trust

and this …

“The Aborigines epitomise what Europe went through with the concentration camps, and everything else. We imported our particular ethos and applied it to that landscape, or moonscape, or whatever you are going to call it. We deprived both the landscape and the people who are in it – who have been in it for 40,000 years and have learned to love it, to adore it, and to worship it. It was their sustenance and their survival, and they made a myth out of their survival. They used to talk at night about, ‘how we survived this day’. Well, we actually ruined all that.”44

Sidney Nolan, Untitled, 1987, collection Sidney Nolan Trust

and this …

“It’s what I have to do when I go out to the Kimberleys now: I have to look at it and say, ‘This is where a great civilisation became doomed’.”45

Was Nolan asking us if we see the Divine in these images? Should we be?

Is he asking us “Is this how we treat our God?”

The Divine in Soldiers

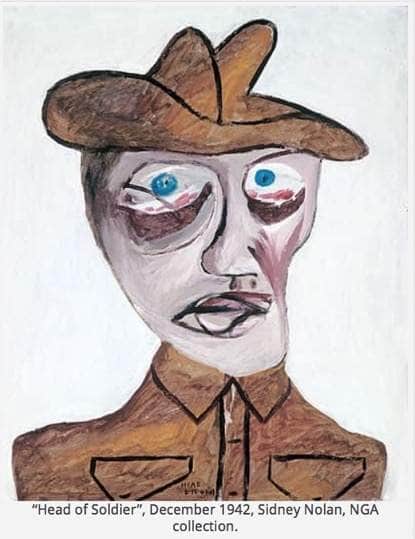

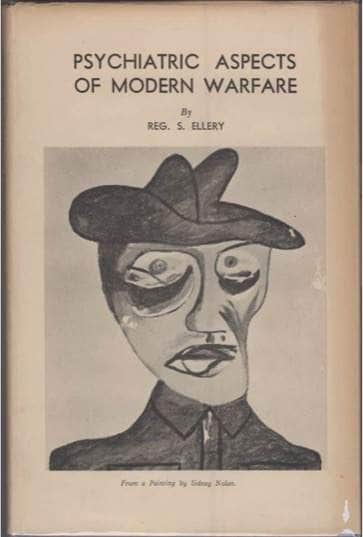

And is there a Divine in Nolan’s images of soldiers?

Is he inviting us to see the Divine in this work from 1942 – the middle of WW2. What bleak haunted eyes this soldier has! Is Nolan saying ‘Here’s what war does to those made in the image of God.”

That image was used on the dust jacket of a book called The Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare.

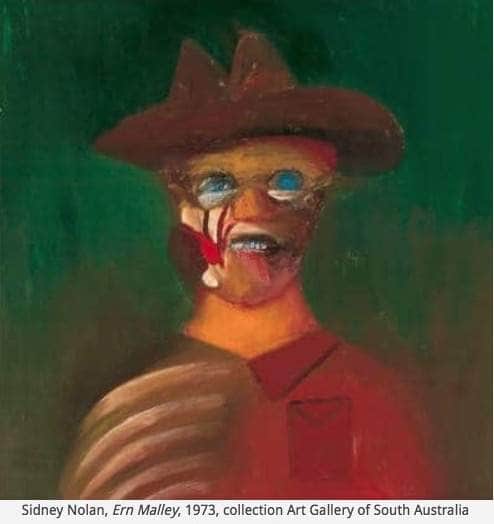

In the mid 1970s Nolan painted this startling portrait of Ern Malley, the poet who never was. Nolan said:

“… Ern Malley says … ‘What would you have me do? Go to the wars?’ … So he has got the digger hat on … He’s got a shell thrust in the face and I’ve made him half a carcass to show he is half ghost and half what happens when you go to the war and you come back.”46

This man who paints what he wants to say, what’s he saying here?

And what’s he saying about the Divine in this diptych held in the War Memorial collection. He’s called it, quite simply, Gallipoli.

Behind it there’s a story.

Shortly before the end of the war, with Nolan still AWL and in hiding, his young brother was drowned in Cooktown harbour on return from active duty. For the Nolan family the whole saga of one son’s death and the other’s desertion must have been completely devastating.

Then over a twenty year period Nolan painted a huge array of Gallipoli-themed works, and In 1978 he gave 250 of them to the War Memorial in memory of his brother. Gallipoli is just one of those.

Here we see a water-borne writhing mass of tangled humanity – some seemingly half-alive, others seemingly dead. Is Nolan asking here: Just how do we treat those made in the image of the Divine? And what does that say about humankind?

In this painting there is no Divine sitting up there on high. To the extent that one might claim a Divine in this work of Nolan’s – and why should we not? – here the Divine is down where it’s dirty, in the watery graves, in the trenches … and, I reckon, on both sides of the conflict.

A common reading of this painting sees the large left-most figure as Nolan’s father attempting to save his son’s life and rescue him from the Cooktown waters. I see it the other way round. Nolan’s brother carrying his father on his shoulders. Perhaps across the River Styx – who knows – pre-war, the boat from which Boy Nolan drowned was a car ferry on the Hawkesbury.47 Who pays the ferryman? Nolan himself is thought to be the slightly highlighted figure to the right in the left panel.

Moving on now, we also find the Divine in Nolan’s paintings of the natural world.

The Divine in the Lilies of the Field

”Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin. And yet I say unto you that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.” Matthew 6: 28

What does Nolan have to say about this?

Sidney Nolan, “Flowers”, 1985, private collection

“I saw the flowers springing up in Central Australia after they had lain dormant in the sand for twenty years. The pitiless wasteland throws up this extraordinary garden – like the Paradise Garden of the Islamic peoples.”48

Speaking about a poem by 18th century poet Christopher Smart, Nolan said

“Smart says some rather extraordinary things about flowers, ….flowers are the symbols of God and so on. So I did a whole series of paintings of flowers …”49

Here we have a huge spray painting done seven years before his death. It’s Nolan’s ‘symbol of God’- to use his own words.

Sidney Nolan, “Snake”, 1970-72, (detail), collection MONA

And he spoke of

“… doing an enormous series of flower paintings called Snake, ….”

Sidney Nolan, “Snake”, 1970-72, collection MONA

… it more or less consists of 1500 paintings – it’s 120 feet long and 20 feet high …. and it more or less consists of all the wild flowers that can come up in the desert in Central Australia. There’s a kind of Paradise. When it rains there these flowers come up, some of which have been dormant for 50 years, the seeds have been.”50

Once again – what’s being painted here by the man who says “I’d rather paint what I have to say than say what I have to say”? Is this another take of his on the Divine?

Perhaps we best saw Nolan’s paintings of a divine creation in those marvellous central Australian landscapes we looked at in the Sublime. Let’s now look more specifically at one narrow aspect of this landscape.

The Divine in the Land

In the 1960s Nolan collaborated on a number of books with West Australian poet and writer Randolph Stow. Mick Stow was 20 years younger than Nolan and he’d won the Miles Franklin Award with his novella To the Islands. This astonishing book concludes with Heriot, an ageing disillusioned Mission Station supervisor up in the Kimberley, walking a metaphorical end-of-days journey to the coast with a young Aboriginal friend.

Friedrich, “The Monk by the Sea”, 1808-1810, collection Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

He looks out over the Arafura Sea to the Aboriginal islands of the dead. “‘My soul,’ he whispered, over the sea-surge, ‘my soul is a strange country.’” Could any words better evoke the ethos of Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea? Or of Nolan’s Ned Kelly?

Nolan did the illustrations for Outrider, a book of poems by Mick Stow.51 One of these poems is called “The Land’s Meaning” and Stow dedicated it to Nolan. Here’s Nolan’s illustration.

Sidney Nolan, “The Land’s Meaning”

And what is the land’s meaning shown here? Let’s listen to Stow’s words:

The love of man is a weed of the waste places,

One may think of it as the spinifex of dry souls.

…. What is God, they say,

but a man unwounded in his loneliness?

…. a skin-coloured surf of sandhills jumped the horizon

and swamped me. I was bushed for forty years.

And I came to a bloke all alone like a kurrajong tree.

And I said to him: ‘Mate – I don’t need to know your name –

Let me camp in your shade, let me sleep, till the sun goes

down.’

I’ve read that in this poem the topography of the interior of Australia becomes the topography of the mind and of a universal concept: caritas, charity, the Christian ‘love of man’.52

Perhaps here we see the ultimate collaboration, Nolan painting not just what he wants to say, but what Stow has said. Something of immanence, something that’s down here, out there – not up there. Perhaps that ‘something’ is love – which is what many see as the quintessential essence of the Divine.

The Divine in Parables of Sunlight

Finally … almost … why have I titled this talk parables of sunlight? All will now be revealed.

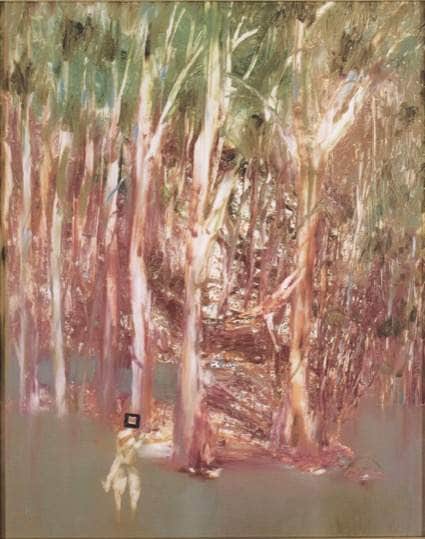

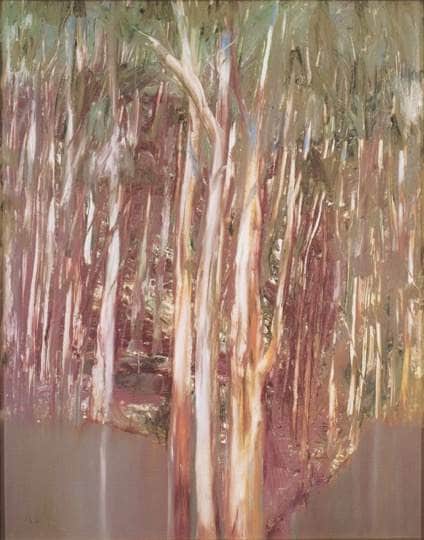

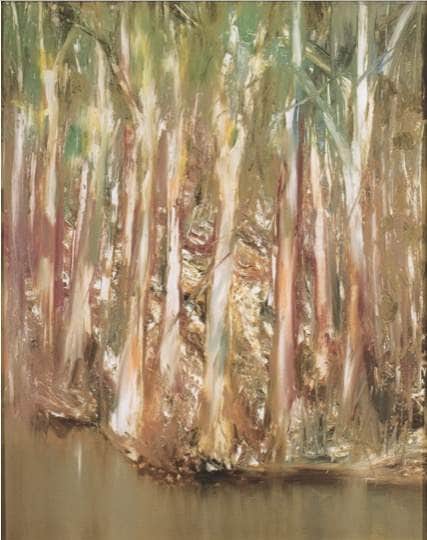

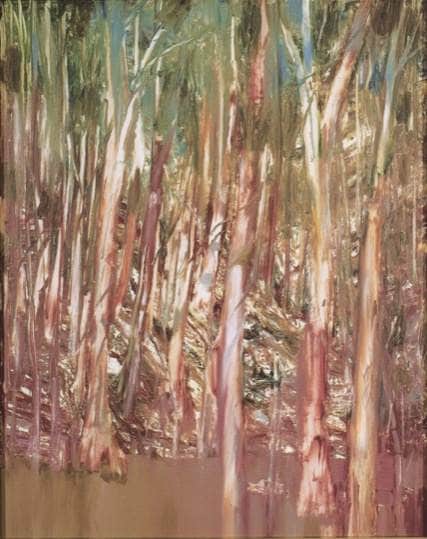

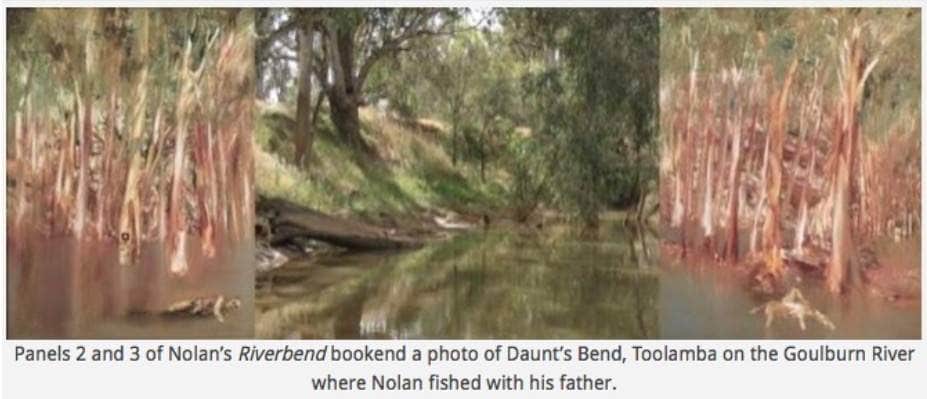

The Goulburn River near Toolamba, Victoria

This bend in the Goulburn River is near the little Victorian town of Toolamba about 20K south of Shepparton, where Nolan’s extended family lived. When he was a boy he’d go here on family holidays. He’d fish here with his father. His mother would walk along the riverbank with him as a baby, and nurse him.

He’s supposed to have camped here for some days in 1964, soaking up the atmosphere again perhaps.

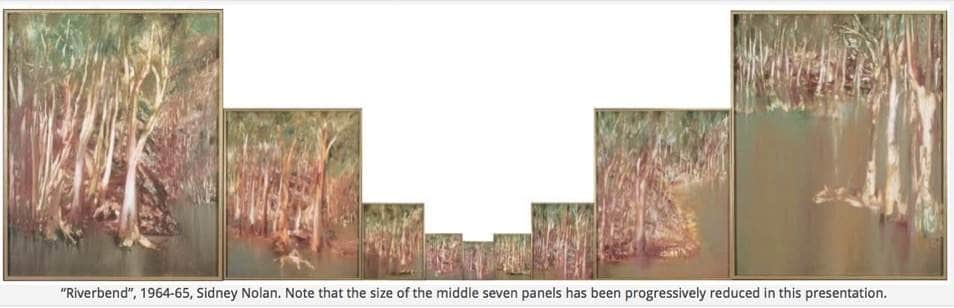

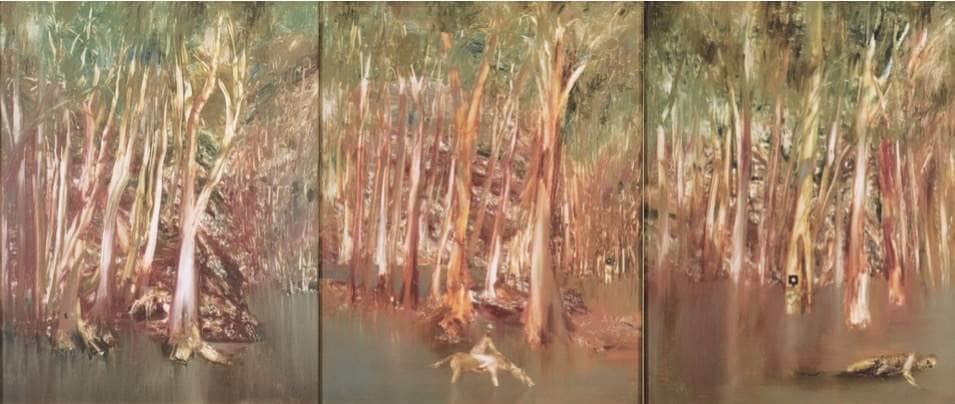

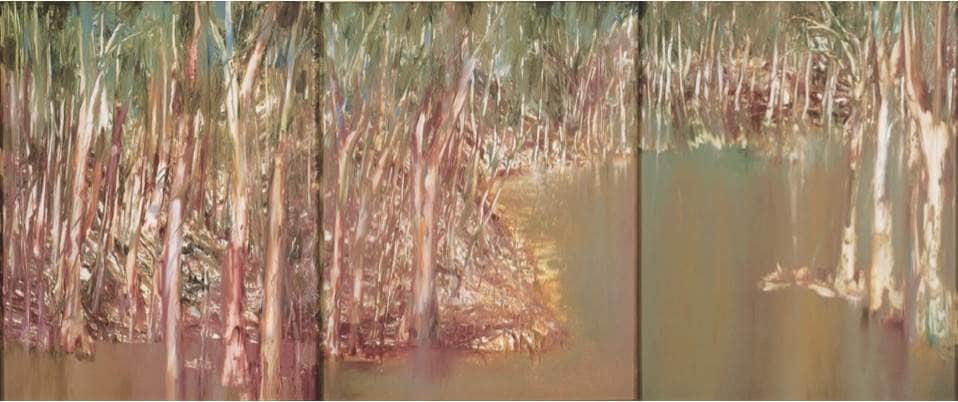

And then over that New Year he painted it. Riverbend.

Nine magnificent panels – each 6 feet by 5 – the whole work 11 meters long – all nine panels completed in three inspired bursts over a 19 day period. I’m convinced it is his greatest work.

The good news, as some of you know, is that this masterpiece is on permanent display right here in Canberra – in the Drill Hall Gallery at the ANU. In the sequence of images that follow, I’ve tried to give another perspective on this great work. As the images scroll through, I’ll read about Riverbend.

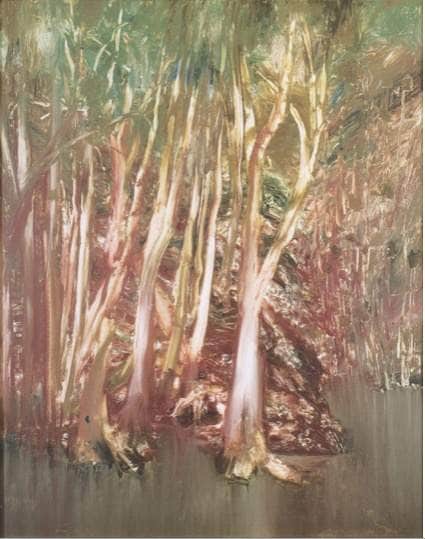

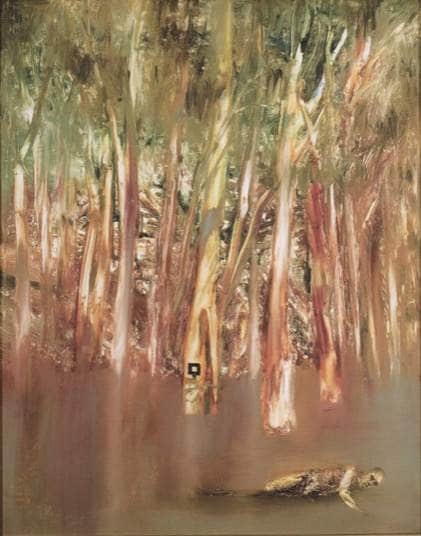

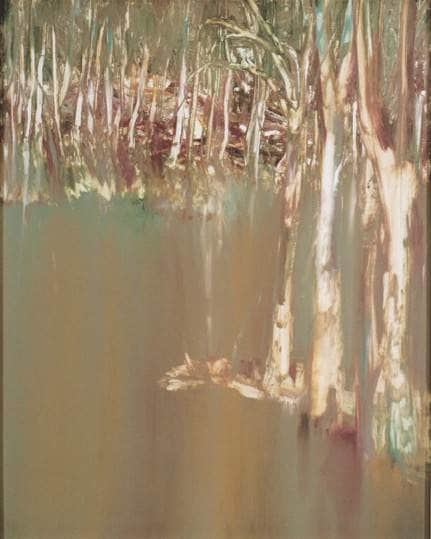

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 1), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 2), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 3), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 4), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 5), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 6), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 7), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 8), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panel 9), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

In his mid-60s Nolan spoke about this stretch of river:

“It was along this river that I was brought when I was about, I suppose about six weeks old. And I was fed by my mother … in a log cabin … I still think about my mother, the river is still there, the river runs.”53

He dedicated the painting to his father, but Sid Snr never saw it. He died just a few weeks before Riverbend was first shown in Australia.

Barry Pearce curated the 2007 Nolan retrospective for AGNSW. He regards Riverbend as “an elegiac nine-panel masterpiece, arguably Nolan’s greatest.” He said that it “stands supreme, a symphonic homage to Nolan’s childhood memory … through his dreamlike, stereoscopic recall of the Goulburn River.”54

In this composite image, two of the Riverbend panels book-end a photograph of the river, and you can see just how effective Nolan’s evocation of the whole scene has been.

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panels 1-3), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

And in a last scroll through Riverbend, three panels at a time, I’ll read from Dylan Thomas’ Poem in October,55 which begins with those well known lines “It was my thirtieth years to heaven ….”

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panels 4-6), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Thomas wrote it on his 29th birthday. He walks out into the countryside, and suddenly memory transports him back to childhood and he says:

And I saw in the turning so clearly a child’s

Forgotten mornings when he walked with his mother

Through the parables

Of sunlight

And the legends of the green chapels

….

Sidney Nolan, “Riverbend”, (panels 7-9), 1964-65, collection ANU Drill Hall Gallery

Where a boy

In the listening

Summertime of the dead whispered the truth of his joy

To the trees and the stones and the fish in the tide.

And the mystery

Sang alive

Still in the water

Flame out, like shining

I’ll finish with this final take on the Divine in the work of Sidney Nolan.

Sidney Nolan, “Landscape”, 1947, collection NGA

This is the first painting in his first Kelly series. It’s simply called Landscape. It brings to mind a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Nolan was familiar with Hopkins. I’ll read from “God’s Grandeur”.56 Perhaps it is to these words that Nolan’s paintings of the Divine respond:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, ….

Sidney Nolan, “Landscape”, 1947, (detail), collection NGA

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Nolan’s Australian landscapes are always light filled – whether it’s the clear enveloping light of the blue skies in the Kelly paintings, the harsh light of the red desert, that filtered light flickering through the trees of Riverbend, or the mysterious light blazing on the horizon here in this last Landscape.

It is always the light he seeks to capture. As he himself said:

“It’s God’s gift to the world …. a wonderful light that shines upon it and makes it ethereal.”57

Perhaps it was in this Australian light, that Nolan most intensely felt what Hopkins saw when he wrote “The world is charged with the grandeur of God. It will flame out, like shining from shook foil”.

There’s a Jewish saying that at the Final Judgement the only question God will ask us is this: “Did you enjoy my world?”

Shortly before he died Nolan did an interview with the ABC’s Sally Begbie. It was, in effect, his last major statement to the world. In that last interview Nolan said this:

“If the Lord said to me well, have you had a good innings, I’d say yes. How about you?”58

Which is so deceptively flippant – just like his daughter said.

END NOTES

- Albert Tucker in conversation with Betty Churcher and Stuart Purves, interviewed by Philip Adams on “Late Night Live”, ABC, 30 November 1992. http://www.abc.net.au/rn/features/inbedwithphillip/episodes/224-the-sidney-nolan-legacy/ retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Quoted on website for “Sidney Nolan: a new retrospective”, AGNSW, Sydney,2007; see http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/sub/nolan/home.html retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Nolan interview with Bernard Smith, 1961; quoted by Frances Lindsay, “Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier” in Barry Pearce et al, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, Sydney 2007, p. 72.

- Nolan Interview with Bernard Smith, April 1962; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, Viking, Melbourne, 2007, p. 244.

- Nancy Underhill Sidney Nolan: a life, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015, p. 295.

- TV Times, 28 January 1070, quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 238.

- Angry Penguins No 2, Adelaide University Arts Association, Adelaide, 1941, p. 41.

- For more information on these works, see you, Lady, are the Tree: Nolan’s annunciation on this website.

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan: Landscape and Legends, A Retrospective Exhibition 1937-1987, University of Cambridge, p. 40.

- Interview, Edmund Capon, Sidney Nolan in China, exh. cat., AGNSW March-May 1981; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 239.

- interview with Garry Kinnane, “The artist and two authors” The Age, Melbourne, 10 April 1982; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 300.

- Barrie Reid, with whom Nolan travelled in Queensland in 1947, has written “I realised that very little which Nolan did was unfocussed, arbitrary or amateur.” Barrie Reid, ‘Nolan in Queensland; some biographical notes on the 1947-8 paintings,’ Art and Australia, op. cit., p. 447.

- Sidney Nolan, letter to Bert Tucker, 1 April 1951, quoted in Bert & Ned, Patrick McCaughey , Meigunyah Press, Melbourne 2006, p. 26.

- Nolan Interview with Bernard Smith, April 1962; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 244.

- Sidney Nolan notes, Sydney, 2 December 1951, Jinx Nolan Papers; quoted in Geoffrey Smith, Sidney Nolan: Desert and Drought, NGV, Melbourne, 2003, p. 84.

- Cynthia Nolan, Outback, 1962, p.163; quoted in Geoffrey Smith, Sidney Nolan: Desert and Drought, NGV, Melbourne, 2003, p. 88.

- Sidney Nolan, diary notes, RMS Orcades, 10 September 1950. Jinx Nolan Papers; quoted in Geoffrey Smith, Sidney Nolan: Desert and Drought, NGV, Melbourne, 2003, p. 98.

- Artist’s diary, March 24, 1952; quoted in Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, op. cit., p. 162.

- Rosemary Crumlin, Images of Religion in Australian Art, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1988, p 48.

- NLA, Papers of Sir Sidney Nolan, MS10245, Series 4, file 239. I am indebted to Andrew Turley for bringing to my attention these photos of Nolan’s, as well as another crucifix painting with an image from Nolan’s African series.

- quoted by Brian Adams, Quadrant, April 1978 ; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 238.

- Elijah Moshinsky, No.15 in The Nolan 100, Study for ‘Samson et Dalila’, http://www.sidneynolantrust.org/nolan-100/15-study-for-samson-et-dalila-elijah-moshinsky, retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Bede Griffiths, Marriage of East and West: A Sequel to The Golden String, Templegate Publishers, 1982.

- interview with Charles Spencer, ‘Speaking with Sidney Nolan, the Australian heroic dream,’ in Studio International, 1964, p. 204.

- See “Nolan’s Journey to Paradise”, The Australian Magazine, 21-22 October 1989; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 303.

- Charles Spencer, ‘Speaking with Sidney Nolan, the Australian heroic dream,’ in Studio International, 1964, p. 205, 208.

- Amelda Langslow, email to author, 30 June 2018.

- Hugh Curnow, “The Pain and the Glory,” The Bulletin, March 20, 1965; quoted by Lyrica Taylor, STILL SMALL VOICE: British Biblical Art in a Secular Age (1850-2014) from the Ahmanson Collection, The Wilson (Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum), Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, 2015.

- Charles Osborne, Masterpieces of Nolan, London, Thames and Hudson, 1975; quoted by Lyrica Taylor, STILL SMALL VOICE: British Biblical Art in a Secular Age (1850-2014), op. cit.

- Vasili Rozanov (1856-1919) was a pre-Revolutionary Russian commentator on the philosophy of religion and politics, who would hold a mirror to conventional wisdom by expressing contrary views. It was actually he, not Winston Churchill, who coined the phrase ‘Iron Curtain’ – “With a rumble and a roar” he said, “an iron curtain is descending on Russian history”. Churchill borrowed from Rozanov when speaking of the Stalin regime.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: A Modern Painters Interview with Sir Sidney Nolan,” Modern Painters, Vol.1, No.2 (Summer 1988); quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 344.

- In Sweden to accept the Nobel Prize on Patrick White’s behalf, Nolan was asked to be the Australian among 33 national artists producing works on paper in homage to the prize. Galerie Börjeson in Malmö, Sweden invited one artist from each country which to that point had produced a Nobel laureate to submit a work. They were sold in limited editions and were later all published together with other works of each artist. See Moderna Mästare, Galerie Börjeson, Malmö, 1978. Nolan’s work is on p.327.

- Elizabeth Langslow, No. 100 in The Nolan 100, http://www.sidneynolantrust.org/nolan-100/100-the-galaxy-elizabeth-langslow, retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Alan Moorehead, September 1965: quoted in Rodney James, “Desert of Ice”, Sidney Nolan: Antarctic Journey, Morningside Peninsula Regional Gallery, 2006, p. 29.

- ibid, p. 59.

- In August 1987 Nolan wrote a poem The Oz Digger (see Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 446) that draws on some conversations about an extra dimension in life. It goes: “the painter Brett Whiteley asked us which we considered the wonders of the world?” Nolan answers quickly: “oh lord / oh extremity / there is only one / living and dead / it is a floating nun”. This alludes to a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem of great religious faith, The Wreck of the Deutschland. In the actual wreck of the ship Deutschland in 1875, five Westphalian nuns bound for the USA drown while proclaiming their faith. But Nolan parodies Hopkins – he doubts and wonders whether the nuns “there then met / the Master / of jay-blue heaven / and belled fire”. For Nolan the wonders of the world were not these, but rather “… the jar / of the cart / my father drove me in, / the Antarctic mist / on the many fleeces / Sweet heaven in pieces”.

- Alan McCullough, September 1963; quoted in Rodney James, “Desert of Ice”, Sidney Nolan: Antarctic Journey, Morningside Peninsula Regional Gallery, 2006, p. 55.

- Alan Moorehead, May 1965: quoted in Rodney James, “Desert of Ice”, Sidney Nolan: Antarctic Journey, Morningside Peninsula Regional Gallery, 2006, p. 28.

- Elwyn Lynn, September 1963: quoted in Rodney James, “Desert of Ice”, Sidney Nolan: Antarctic Journey, Morningside Peninsula Regional Gallery, 2006, p. 48.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: A Modern Painters Interview with Sir Sidney Nolan,” op. cit., p. 344.

- Sidney Nolan, quoted in Elwyn Lynn and Sidney Nolan, Sidney Nolan – Australia, Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, p. 13.

- Damian Smith, No. 20 in The Nolan 100, Brian the Stockman at Wave Hill Station Mounting a Dead Horse, http://www.sidneynolantrust.org/nolan-100/20-brian-the-stockman-at-wave-hill-mounting-a-dead-horse-damian-smith, retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Interview, Jancis Robinson, Thames ITV, 15 December 1987; quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 295.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: A Modern Painters Interview with Sir Sidney Nolan,” Modern Painters, Vol.1, No.2 (Summer 1988); quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 344.

- ibid, p. 349.

- Interview, Earle Hackett and Elwyn Lynn, ABC Time Exposure, ‘Sidney Nolan and Ern Malley: Beyond is Anything’, 1974; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit., p. 259.

- The vessel on which Raymond Nolan was serving when he drowned in Cooktown Harbour was AB 442, the requisitioned car ferry Frances Peat from Peat’s Ferry on the Hawkesbury River north of Sydney. After the war and renamed the Alexander Allison, she plied Auckland Harbour, until sinking in 1961 when under tow to Hobart.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: op. cit.; quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: op. cit., p. 351.

- Interview, Donald Mitchell, Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh, Suffolk, 11 June 1990; quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: op. cit., p. 358.

- ibid., p. 364.

- Randolph Stow, Outrider, MacDonald, London, 1962.

- Martin Leer, “Mal du Pays: Symbolic Geography in the work of Randolph Stow”, Australian Literary Studies, 1991, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 3-25.

- Sidney Nolan, in ABC film Sidney Nolan: an Australian dream, 1983; quoted by Barry Pearce in his essay “Planet Nolan”, Transferences: Sidney Nolan in Britain, ed. Rebecca Daniels, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester UK, 2017, p. 29.

- Barry Pearce, “Planet Nolan”, ibid.

- see https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=24096 retrieved 4 August 2018.

- see https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44395/gods-grandeur retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, op. cit.

- Interview, Sally Begbie, The Rodd, 1992; quoted in Nancy Underhill, Nolan on Nolan, op. cit.,, p. 304.

One Comment

Join the conversation and post a comment.

Dave congratulations, what a fabulous, comprehensive thought provoking presentation. We had absolutely no idea of the vast extent of Nolan’s work. Thank you so much for his work to our attention.