David Rainey’s preview of the upcoming exhibition at the Art Gallery of Western Australia of Sidney Nolan’s 26 Ned Kelly paintings from The National Gallery of Australia, has been written especially for SeeSaw, the Perth-based Arts Alert, Preview and Review website https://www.seesawmag.com.au

Ned and Sid, Sublime at AGWA

Ned Kelly is visiting the Art Gallery of Western Australia; or to be more precise, twenty six Kelly-themed paintings are making their first visit to the West.

However a recent excursion by Kelly himself to these parts went largely unnoticed and eluded the vigilance of many.

Here is a little known tidbit of bushranging history: Joseph Johns, aka Moondyne Joe, was a childhood hero of Kelly who revered the Welshman turned bushranger.

SeeSaw can now reveal that Kelly, weaned on the teat of Moondyne bravado, posthumously visited the West in search of his alter ego. He was captured, so to speak, whilst surreally taking cover behind a telegraph pole outside the Lower Chittering Volunteer Fire Station.

Ned Kelly sighted at Lower Chittering

Later that day he bailed up the Year 3 class at Toodyay Primary, holding children hostage until they painted his portrait. The images collected here seem to corroborate the Chittering sighting.

Each child interviewed strongly recommends that you visit AGWA’s exhibition of Kelly paintings by another artist, Sidney Nolan. It opens 11 August and runs until 12 November.

Ned Kelly portraits at Toodyay Primary School

This preview takes a wry look at what is there to be seen at AGWA and also at what will not be seen. Nolan said that Kelly’s own words were ingredients in these paintings, and so here we borrow Nolan’s own words to tell the tale.

First though, a more conventional summary.

Nolan visited Glenrowan, the site of Kelly’s capture, in April 1946 with fellow ‘Angry Penguin’ Max Harris. He had already painted at least one of the so-called ‘first series’ Kellys and would complete them over the next fifteen months. With one exception they were painted on the dining table at Heide, the home of wealthy modernist art enthusiasts John and Sunday Reed with whom Nolan had lived in a ménage à trois since the collapse of his first marriage in 1941.

Soon after he painted The Watch Tower in July 1947 Nolan left Heide, and would return only briefly. The parting was strained, and his relationship with the Reeds became increasingly acrimonious over time – his second marriage, to John Reed’s sister Cynthia in March 1948, but the first barrier.

At the time he readily conceded

“I do not even feel that the Kellys belong to anyone else other than Sun”1

and cooperated with the Reeds in selecting 27 paintings from the total of about three dozen which remained at Heide. He assisted in providing text for their initial public hanging at the Velasquez Gallery in Tye’s Furniture Store in Melbourne in April 1948.

However by 1971 his attitude had very much changed. In his poem Fidelio he lamented “the man with the iron mask and the robin on the fence” being in a bank vault “buried without being dead.”2

Do try to locate that robin in this exhibition. It’s there to be seen in one of the works, a visual signature by Nolan referring to the alias ‘Robin Murray’ which he used when AWL during and after the war. As he explained it in 1991:

“that was maybe Sunday’s idea … she always called me Robin, that’s robin red breast.”3

“The robin on the fence”

In 1977 Sunday Reed gave 25 of the 27 Kelly paintings, “with love” as she insisted the deed record, to the National Gallery of Australia – one, Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek, having been privately purchased from Nolan when it was first exhibited in May 1946 (as seen below); and a second, First Class Marksman, having been re-acquired by Nolan.

Sidney Nolan, “Ned Kelly at Stringy Bark Creek”, (now known as “Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek”), March 1946, No 40, City of South Melbourne Arts Festival, South Melbourne Town Hall, May-June, 1946

First Class Marksman has been exhibited with all the others on only a few occasions, the last in 1997. Marksman will not be making an appearance at AGWA. It has always been the outlier – the only one not painted at Heide but at Vassilieff’s home “Stonygrad,” the only one not in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia but rather with the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the only one that reverted to Nolan’s own possession. It holds the record for the highest price achieved at auction by an Australian artist – $5.4 million in 2010.

Sidney Nolan, “First-Class Marksman”, December 1946, collection AGNSW

In the mid-1960s, Max Harris railed against British critics who lionised the Kelly paintings as “a deep and complex interpretation of a myth of Australian nationhood, and a unique view of the relationship of the Australian man to his environment. Australians, say the subtle London critics, tend to lose their identity, become iron masks behind which is nothing, in the harsh Australian landscape”

“Bum!” exclaimed Harris, “…. Kelly is, in this famous sequence, purely Nolan’s alter ego, a virility symbol, and the series exists as a catharsis of Nolan’s basic insecurities.”4

Later in life Nolan admitted

“Really the Kelly paintings are secretly about myself. You would be surprised if I told you. From 1945 to 1947 there were emotional and complicated events in my own life. It’s an inner history of my own emotions’.”5

There are certainly similarities between the painted and painter. Both were fugitives from the law – Kelly a bushranger with a price on his head, Nolan absent without leave from the army; both had Irish roots, although Nolan’s much vaunted Irish heritage was Northern Ireland Protestant, not the Catholic roots of Ned Kelly. Nolan never bothered to correct this misapprehension – over time it would serve him well.

Other images invite speculation. Does the figure of Mrs Reardon, seen in the Glenrowan paintings fleeing the burning inn with her young daughter, bring to mind Nolan’s first wife Elizabeth fleeing the conflagration at Heide with their young daughter Amelda?

Sidney Nolan, “Mrs Reardon at Glenrowan”, October 1946, collection NGA

Indeed, it is a remarkable coincidence that an untitled painting of this time, known as Mrs Reardon and Child goes to auction in Sydney just two days before the AGWA show opens.6 This work adds credence to the above speculation. Nolan kept this painting all his life and on his death in 1992 it went to Amelda. Dated 27 January 1946, a period of intense personal turmoil for Nolan – in July 1945, Elizabeth had been granted a divorce on the grounds of his desertion, and two months later with Nolan deserted from the army, his young brother Boy drowned in Cooktown on return from active duty – the pervasive lyrical beauty of this painting reaches into this 21st century with a poignant tranquility.

Sidney Nolan, untitled, (“Mrs Reardon and child”), January 1946, private collection, Victoria.

We can also speculate as to why Nolan cut the original 6 ft x 4 ft Glenrowan painting in half to produce the Burning and the Siege. Was it simply because Peter Bellew suggested it was too large, or is there something more significant about the parting? Burning and Siege are seen here flanking a photo showing the original painting before being halved.

Sidney Nolan, “Burning at Glenrowan”, Oct 1946, on left, and “Siege at Glenrowan”, November 1946, on right, flanking 1946 photo of Kelly paintings at Heide; collection NGA

And did Nolan replace a very look-alike figure with a trooper in the photo of Longreach in Walkabout magazine on which he based The Watch Tower, the very last of the first series Kellys? He painted it only a few weeks before departing Heide at a time when he was surely on the lookout to get out.

(L) Longreach, “Walkabout Magazine”, March 1947; (R) Sidney Nolan, “The Watch Tower”, July 1947, collection NGA

In 1961, at the time of his exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery in London, Nolan said that

“Kelly’s own words, and Rousseau, and sunlight are the ingredients of which they (the Kelly paintings) were made.”7

The Rousseau influence can be seen nowhere better than in this flanking of Rousseau’s painting War by, above, the clouds of Nolan’s Encounter, and below, by the black steed of his Evening.

Sidney Nolan, detail from “The Encounter”, 1946, above, and detail from “The Evening”, 1947, below, both collection NGA, flanking Henri Rousseau, “War”, 1894

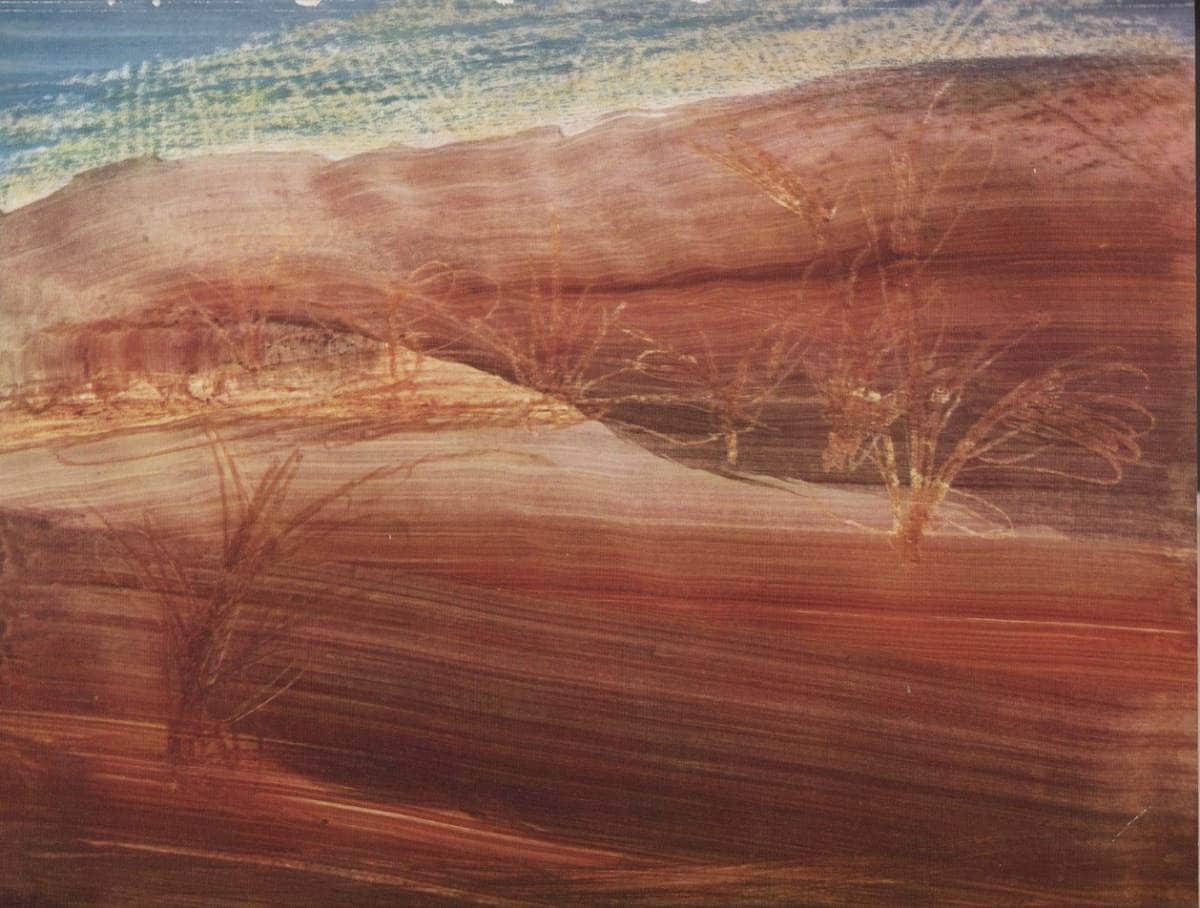

As for sunlight, few artists can hold a candle to Nolan when it comes to capturing the light and the colour of the Australian bush and the outback. In 1988 he spoke of

“the implacable, beautiful landscape … How can one put it? It’s God’s gift to the world. In Australia there’s a wonderful light that shines upon it and makes it ethereal…”8

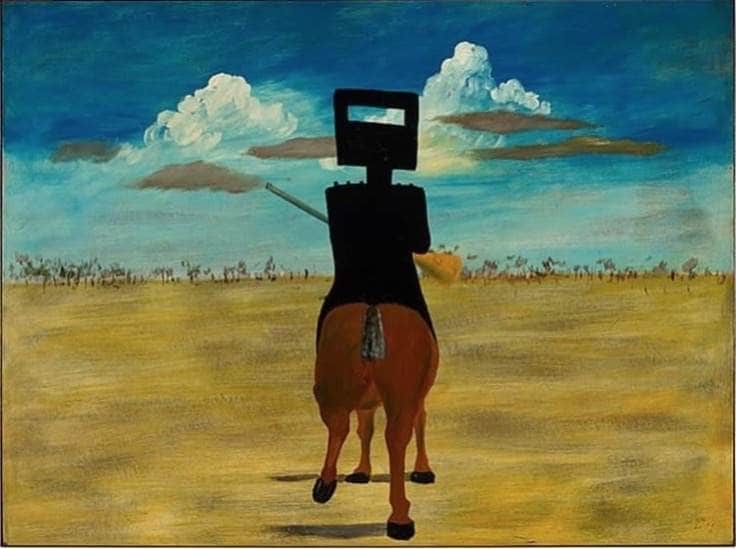

Be sure to concentrate on the light when you visit these paintings. And if perchance, like quite a few others, you have trouble with Nolan’s rather naively styled portrayals of characters in the story, simply ignore them and imagine the paintings without any figures at all. Imagine just the landscapes.

Four years before he died Nolan linked the Kimberley to his famous Kelly image via Casper David Friedrich’s painting Monk by the Sea. He said,

“It’s the same feeling you get with Friedrich and his famous picture Monk by the Sea. This shows a single figure of a man looking out by the sea; he’s seen from behind. That’s the same as Ned Kelly in that key painting where he’s on the horse looking out into nothing.”9

Here we see the Romantic Sublime of Friedrich alongside the Colonial Sublime of Nolan.

(L) Casper David Friedrich, “The Monk by the Sea”, 1803, collection Berliner National Gallery, (detail); (R) Sidney Nolan, “Ned Kelly”, September 1946, collection NGA

Friedrich’s painting Monk by the Sea, the quintessential image of the Romantic Sublime, brings to mind so clearly those marvellous last words in Randolph Stow’s novella To the Islands. Heriot, the ageing disillusioned Mission Station supervisor up in the Kimberley, has walked a metaphorical end-of-days journey to the coast with his young Aboriginal friend. He looks out over the Arafura Sea to the Aboriginal islands of the dead: “‘My soul,’ he whispered, over the sea-surge, ‘my soul is a strange country.’” Could any words better evoke the ethos of Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea? or of Nolan’s Ned Kelly?

In the 1960s Nolan and Stow collaborated on a number of books including Outrider, an anthology of poems by Stow, for which Nolan did the illustrations.10 One poem, “The Land’s Meaning”, Stow dedicated to Nolan.

Sidney Nolan, “The Land’s Meaning”

With what meaning has Nolan painted the land seen here? Let Stow speak:

The love of man is a weed of the waste places,

One may think of it as the spinifex of dry souls.

…. What is God, they say,

but a man unwounded in his loneliness?

…. a skin-coloured surf of sandhills jumped the horizon

and swamped me. I was bushed for forty years.

And I came to a bloke all alone like a kurrajong tree.

And I said to him: ‘Mate – I don’t need to know your name –

Let me camp in your shade, let me sleep, till the sun goes down.’”

Sidney Nolan, “Ned Kelly”, 1946, collection NGA

Nolan always saw his Kelly paintings as more than the Kelly narrative, and so should we. As he put it in 1978:

“I wanted a visual form of the ‘otherness’ of the thing not seen.”11

And he told his friend Jack Lynn,

“I like what an historian [Steven Runciman] said of the Kelly series: ‘They are really stations of the Cross’.”12

With time, perhaps Nolan discovered a personal Via Dolorosa in the Kelly paintings.

Sidney Nolan, “Kelly”, 1959

The best advice to take into this exhibition was given by Max Harris, who visited Kelly country with Nolan back when it all began. “Look at the painting by all means ….” Harris said in 1989, “but also look into the heart of the matter. If you miss that, you miss everything.”13

END NOTES

- Sidney Nolan, Letters to John Reed, 14 January 1948, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 2, File 6.

- Sidney Nolan, “Fidelio”, in Paradise Garden, R Alistair McAlpine Publishing Ltd, London, 1971, p. 53.

- See Sidney Nolan interviewed by Michael Heyward, London, 5 April 1991 on this website.

- Max Harris, “Conflicts in Australian Intellectual Life”, in Literary Australia, Ed. Clement Semmler and Derek Whitelock, F W Cheshire, Melbourne, 1966, p. 22.

- Sidney Nolan, comments made to Elwyn Lynn on 6/9/1984 published in Elwyn Lynn, Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly, ANG, 1985.

- see https://www.menziesartbrands.com/items/untitled-mrs-reardon-child-0 , downloaded 2 August 2018.

- Sidney Nolan quoted by Colin MacInnis, “The Search for an Australian Myth in Painting”, in Kenneth Clark et al, Sidney Nolan, London: Thames and Hudson, 1961, p.30.

- Interview with Peter Fuller, “Sidney Nolan and the Decline of the West: A Modern Painters Interview with Sir Sidney Nolan,” Modern Painters, Vol.1, No.2 (Summer 1988); quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 344.

- ibid., p. 349.

- Randolph Stow, Outrider, MacDonald, London, 1962.

- Sidney Nolan, quoted in Elwyn Lynn and Sidney Nolan, Sidney Nolan – Australia, Bay Books, Sydney, 1979, p. 13.

- Elwyn Lynn Papers, Art Gallery of New South Wales, from a tape recorded April 21, 1978 and from phone conversations in 1978, quoted in Nancy Underhill, ed., Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his Own Words (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2007), p. 267.

- Max Harris, Introduction to Angry Penguins, and Realist Painting in Melbourne in the 1940s, Australian Exhibitions Touring Agency, Canberra, 1989, p. 6 .