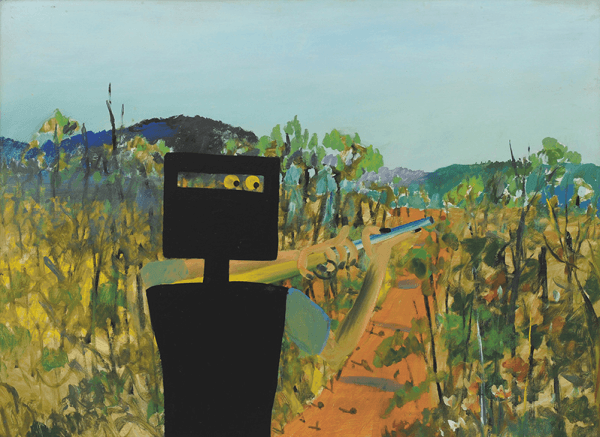

Sidney Nolan’s 1946 painting First Class Marksman is unique on a number of counts. It is the only one of the so-called first series Kellys which was not painted at Heide;1 it is the only work in the first series not in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia;2 it is the one work in the series described by Nolan himself as being pivotal;3 and it holds the record price for a painting by an Australian artist.4

However First Class Marksman is far from unique in having a less than completely delineated provenance. Marksman’s provenance is somewhat indistinct with several listings over the last thirty years having glaring inconsistencies. This article will trace the history, first of the various provenance listings, and then of the work itself, by attempting to resolve the inconsistencies and plug the gaps (or at least identify them).

“First Class Marksman”, Sidney Nolan, December 1946, AGNSW collection.

Provenance is defined in the Oxford dictionary as “a record of ownership of a work of art or an antique, used as a guide to authenticity or quality.” The dictionary lists ‘pedigree’ and ‘history’ as synonyms and increasingly, provenance has come to imply more than a mere listing of ownership, as is reflected in the following Wikipedia definition: “the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object …. the primary purpose of tracing the provenance of an object or entity is normally to provide contextual and circumstantial evidence for its original production or discovery, by establishing, as far as practicable, its later history, especially the sequences of its formal ownership, custody, and places of storage.” This statement must resonate in the Gallery/Museum world post Kapoor.

Listings of the provenance of significant art works most usually appear in either Exhibition catalogues or Auction catalogues, where they serve quite different purposes: in the former to develop an art/art history thesis about the work and/or the painter, in the latter to sell/market/promote the work. A difference in approach is readily appreciated upon reading an auction catalogue as opposed to an exhibition catalogue. The provenance documented by Institutions holding a work can be regarded as a third category of provenance listing, although such listings may not vary significantly from those in the catalogues.

Perhaps one reason why there are inconsistencies and gaps in provenance listings is if there has been a greater emphasis on the significance of custody or location than on devolution of title per se. By way of contrast, there is no Register of title in artworks and the like similar to Registers for other forms of property such as land, bricks and mortar, even motor vehicles. Moreover the significance of actual devolution of title can diminish with time because of a legal maxim commonly expressed in terms such as “possession is nine tenths of the law” – a doctrine which in broad terms favours the rights of the holder as the duration of uncontested possession increases. Furthermore, in certain circumstances, with the passage of time Statute can impose a limitation against action.5

Provenance Listings in catalogues

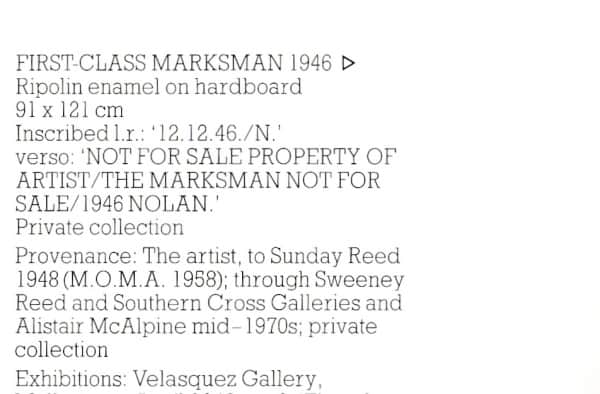

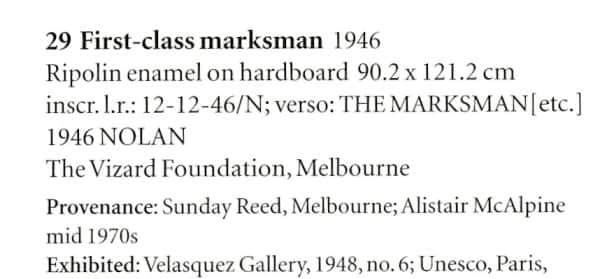

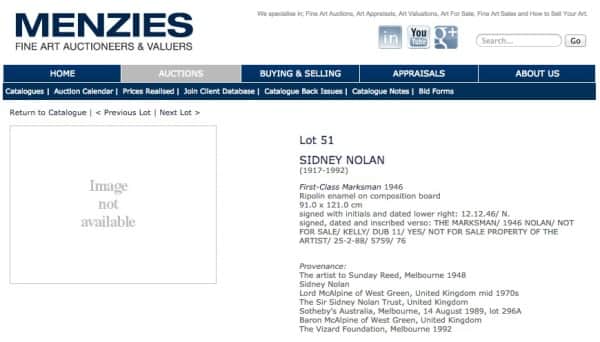

There appear to be no provenance listings of First Class Marksman prior to its exhibition in the Landscapes and Legends exhibition at NGV in 1987. A chronology of provenance listings since then follows, together with images which, rather than mere transcriptions, are included so the reader can view the actual presentations.

1987, Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan: Landscape and Legends, A Retrospective Exhibition 1937-1987, University of Cambridge, p. 76.

“First Class Marksman”, provenance listing, Landscape and Legends catalogue, 1987 p. 76.

1989, Sotheby’s auction 14 August 1989, lot 296A

The description of First Class Marksman (lot 296A) in the Sotheby’s auction catalogue largely follows the text of the Landscape and Legends catalogue. It lists the vendor as the Sir Sidney Nolan Trust, which is perhaps the “private collection” listed in the 1987 exhibition catalogue. There is no list of provenance.

2007, Barry Pearce, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, p. 231

“First Class Marksman”, provenance listing, AGNSW “Sidney Nolan” catalogue, 2007, p. 231

2007, Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, online full catalogue of works for the exhibition, updated with corrections on 12 November 2007

“First Class Marksman”, provenance listing, AGNSW “Sidney Nolan” online catalogue, November 2007.

2010, Menzies auction 25 March 2010, online catalogue

“First Class Marksman”, provenance listing, Menzies online catalogue, March 2010, p. 88

2010, Menzies auction 25 March 2010, Press Release

“First Class Marksman”, provenance listing, Menzies Press Release, March 2010

At the beginning of this article I described Marksman’s provenance as “somewhat indistinct”. A perusal of the listings above suggests this assessment is none too harsh!

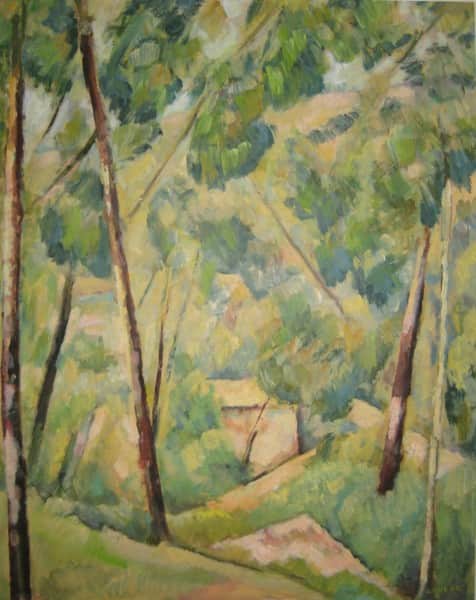

First Class Marksman differs in many respects from its 26 colleagues in the iconic first series of Kellys selected by Nolan in 1948 for their first exhibition at Tye’s Velasquez Galleries in Melbourne. The series was not painted in narrative sequence and Marksman, listed by Nolan as No 6 in this sequence, was painted approximately midway of the 27. It marks a change in tonality within the series, with those painted after Marksman tending to be of darker and more sombre hue than those painted before. It is the only first series Kelly not painted at Heide; it is the only first series Kelly not in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia; it is the only first series Kelly described by Nolan himself as being pivotal;6 it is the only first series Kelly to revert to ownership by Nolan; and it is the only first series Kelly where the vegetation dominates the landscape, sparse as at Warrandyte where it was painted and Cezanne-like in its depiction. Indeed some similarities can be seen in Marksman’s vegetation and its Cezanne-ish styling, and that in Adrian Lawlor’s painting Glimpse from Broom Warren, Lawlor’s home at Warrandyte.

Adrian Lawlor, “Glimpse from Broom Warren,” private collection.

Another distinction, one which appears to have avoided comment hitherto, is that Marksman is the only first series Kelly where Kelly is portrayed Janus-faced. There are five others works in which the eyes in Kelly’s helmet face the viewer, but in none of these does his body face away. On more than one occasion Nolan said the Kelly series were about himself, and the two-faced Kelly in Marksman is perhaps why Nolan regarded the work as pivotal and why he found a way to buy it back. Marksman can be seen as a turning point – a looking forward and a looking back – in his situation at Heide, as much as a turning point in the series itself.

And of course one other point of distinction from the other first series Kellys is Marksman’s provenance. There is little commonality in the provenance listings above other than that Sunday Reed and Alistair McAlpine appear in them all, as does the Vizard Foundation after 1992. Only in the Menzies Press release does McAlpine appear twice as owner. The Sweeney Reed and Southern Cross Galleries pairing, and also MoMAA/MoMADA, appear in one but not the other of the dual provenance listings by both Menzies and AGNSW. Neither Nolan nor the Nolan Trust appear on either AGNSW list. “Private Collection”, that ubiquitous designation of disguise, appears more than once.

A work of such distinctiveness among its first series brethren and the highest priced painting by an Australian artist, it is deserving of better. So here let us take aim, and a pot shot, at the provenance of this First Class Marksman.

1946, the artist, Sidney Nolan

The painting is signed with initials and dated lower right: “12.12.46 / N”

1948, the artist —> Sunday Reed

The year 1948 is commonly ascribed to this devolution of title. However there appears to be no instrument of devolution as such. Nolan left Heide in July 1947 and did not return. The earliest document supporting the contention he regarded the Kellys as belonging to Sunday would seem to be a letter he wrote from Sydney to John Reed dated 14 January 1948 in which, when speaking of making arrangements in Sydney about showing the Kellys, he states “I do not even feel that the Kelly’s (sic) belong to anyone else other than Sun and I cannot visualise in what way I could exhibit them.”7 Nolan’s contesting of Sunday’s rights to the Kellys came much later. Indeed this particular letter, written only a fortnight after he came south from Brisbane and when a return to Melbourne was still within his purview,8 is completely friendly – commencing “Once again will have to ask you if you can to send cheque before end of month,” and concluding “My love to you both and to Sweeney and to Heide & to you [sic] happiness in it.” He would also mention Sunday and the Kellys in a second letter from Sydney several weeks later, saying “I feel the paintings belong to Sun and my thoughts stop there.”9

A number of sources suggest he gave the Kellys to Sunday “as a parting gift” – but absent definite evidence to supporting this contention, it is more likely to be a post hoc assumption.

1956, Sunday Reed —> Gallery of Contemporary Art (GCA)

The Gallery of Contemporary Art was set up under the auspices of the Contemporary Art Society in 1956. The Reeds were its Honorary Directors.10 All 27 first series Kellys were hung in GCA’s Inaugural Gift Exhibition held in their Tavistock Place premises in June 1956. Whether the Kellys returned to the Reeds at Heide after that exhibition is unclear. Nancy Underhill reports that the Reeds ‘donated’ their personal collection to GCA in 1958, two years after the inaugural exhibition.11

1958, Gallery of Contemporary Art —> Museum of Modern Art of Australia (MoMAA)

The GCA and its Honorary Directors soon discovered the financial realities of keeping the doors open to contemporary art exhibitions without government funding. The realities of in-house politics also took hold, as opposing pro-abstraction and pro-figurative factions vied for influence. This led not only to the so-called Antipodean Manifesto in February 1959, but earlier in April 1958 to a new institution being created to replace GCA. Called the Museum of Modern Art of Australia, only John Reed remained as Director and a Governing Council of eleven members, largely business oriented, was appointed.

In one sense the change from GCA to MoMAA could be seen to reflect less an actual devolution of title in Marksman than a change of organisational name. However it is also possible that the ‘donation’ reported as occurring in 1958 was in fact the only ‘donation’ as such and if so, this would imply that GCA never actually held title. Warwick Reeder has written that the Kellys were listed as part of the permanent collection.12

What is quite significant though is that the Reeds’ donation of 160 works which formed the foundation collection, whether initially to GCA or to MoMAA, was conditional. As Reeder has written: “It was not widely known that the donation was conditional on the Museum having sufficient funds to operate, the Reeds having a binding arrangement with the Governing Council that their works would be returned if the Museum closed.”13

Whilst under the MoMAA umbrella the first series Kellys were exhibited twice, first in Melbourne in September-October 1958 in MoMAA’s Tavistock Place gallery, and then at David Jones Gallery in Sydney in February 1959. However the series exhibited was incomplete with Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek, owned by Clive Turnbull, missing. Moreover, and significantly for this present essay, Marksman, which was listed in the catalogues for both Melbourne and Sydney exhibitions, appeared only in Melbourne. If indeed it did travel to Sydney with the 25 others, it was not hung.14

1963, Museum of Modern Art of Australia (MoMAA) —> Museum of Modern Art and Design of Australia (MoMADA)

This variation in the provenance chain occurred with a change of name from the Museum of Modern Art to the Museum of Modern Art and Design of Australia, reflecting the desire of the Board’s new chair, Pamela Warrender, to include ‘design’ in the name in order to appeal to a wider audience. John Reed felt he had not been adequately consulted on the name change, and this was but one of a number of personal dissatisfactions which the Reeds increasingly felt regarding their whole involvement with what they still saw as essentially their own gallery.

Under MoMADA, the first series Kellys were exhibited at George’s Art Gallery in Melbourne in June-July 1963 – in preparation for which the paintings were cleaned, varnished and strip framed.15 Then in June 1964, following restoration by Fred Williams,16 they travelled overseas sponsored by Qantas for exhibition in the Qantas Gallery in London, then in Edinburgh and Paris, and on return in Sydney. However for reasons that have so far eluded my research, Marksman was not among them – only 25 were hung, as was the case with the earlier exhibition at George’s. Nor did it accompany what John Reed now referred to as “the 25 which are held as a unit”17 when they travelled to New Zealand for showing in Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington between March and June 1968.

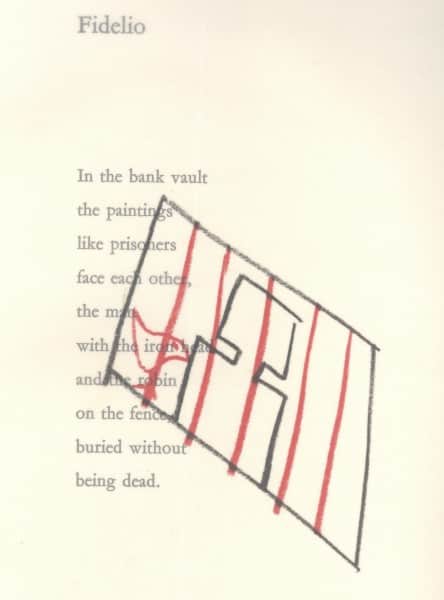

Nolan’s cooperation with the Qantas exhibitions came at a price – his stipulation that the Reeds not accompany the paintings. This fed to their increasing disenchantment with the MoMADA situation. Eventually, on 8 April 1965, John Reed resigned his Museum Directorship and resigned from the Council. Warwick Reeder reports “when John Reed resigned the Reed collection returned with him to Heide.”18 However the Kellys’ new home was not at Heide but rather, following their restoration, in the more secure confines of a bank vault.19 This escaped neither Nolan’s notice nor his ire, as is apparent in his 1971 poem Fidelio.20

Sidney Nolan, “Fidelio” from “Paradise Garden”

1965, after Museum of Modern Art and Design of Australia (MoMADA) is closed —> Sunday Reed

Until quite recently, the question of whether Marksman returned into Sunday Reed’s personal possession at Heide after the demise of MoMADA had been one of some uncertainty, at least on the public record. None of the provenance listings above explicitly state so. Furthermore, in an interesting footnote in the 1987 Landscapes and Legends catalogue, Jane Clark states “First Class Marksman left the Reeds’ possession c. 1959 and is now in a private collection.”21 This footnote could have implied that Marksman did not return to Heide after it was ‘donated’ to GCA/MoMAA and it could have been quite significant if the source of this information was Nolan himself. He did become involved with this exhibition and wished for paintings in his own possession to be referred to in the catalogue as ‘private collection’22– as is Marksman.

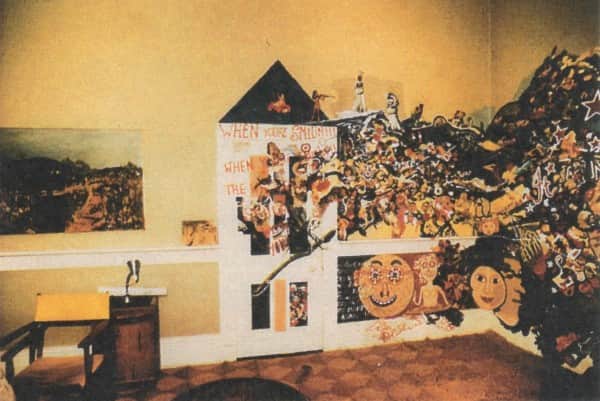

The mystery of whether Marksman was at Heide with the other Kellys was only deepened by its omission from all exhibitions alongside the others after its showing with MoMAA in 1958. If Marksman remained in the Reed’s possession, why was it not exhibited? A reasonable question leading to the apparently logical conclusion that it must almost certainly have left the Reeds’ possession at that time. This remained the conventional wisdom, along with more elaborate theories of skullduggery, until the recent publication23 of a photo showing Marksman on the dining room wall at old Heide in 1969.

Not only had Marksman not been hung with the other Kellys for over 10 years, it may well have not been with them in the bank vault. However it does seem likely, given the strip framing evident in this photo, that it had probably been restored and reframed along with the others in 1963-4.

“First Class Marksman” on the dining room wall at Heide 1 in 1969

In 1963 the Reeds commisioned architect David McGlashan to design a new modern home to be built down the hill from Heide I. They moved into Heide II, as their new home became known, in 1967. By 1969 the Reed’s adopted son Sweeney, recently married, was living in Heide I with his wife Pamela.24

The photo is one of three portraying the mural It Ain’t Necessarily So. Serendipitously named, at least in its juxtaposition to Marksman, the mural stretched across three walls of the Heide I dining room where its artist Mike Brown was temporarily living. It would seem to provide, for the first time, a definite link between Marksman and Sweeney Reed, the next person in Marksman’s provenance chain.

Sunday Reed —> Sweeney Reed

Born in February 1945, the son of artists Joy Hester and Albert Tucker, Sweeney grew up at Heide. Hester left Tucker and Sweeney when the child was two and moved to Sydney with artist Gray Smith upon learning she had Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Later in 1947 Tucker moved to Europe, and from that time the Reeds became Sweeney’s de facto parents, taking him with them when they showed the Kellys in Paris and Rome, and formally adopted him in 1950. Schooled by them initially at Heide, he finished his education as a boarder at Geelong Grammar.

Sweeney travelled to London in 1964 where he worked in the art world, including a stint at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art. Returning to Australia in 1965, the following year he opened his own gallery Strines in Carlton. Strines closed in 1970 and for a few years Sweeney indulged his passion for writing poetry and publishing his own and his friends’ verse. He remained involved in the commercial art world, dealing in pictures, and then in 1972 became more directly involved once again, opening Sweeney Reed Galleries in Fitzroy – initially in partnership with Julian Sterling of Southern Cross Galleries,25 and then on his own until it too closed its doors, unexpectedly midway through a Les Kossatz exhibition, in 1975. He lived at Heide I with his wife and two children until the Christmas before his death in 1979.26

Barrett Reid spoke at his funeral: “Adolescence is usually a tough time for us all, so it was – and more so – with Sweeney. Sometimes he lost himself, got out of touch with himself and those he loved, but even in his darkest times there were paintings and poems and Heide the beloved place.”27 There were adolescent brushes with the law. He was said to have chaotic business practices and his step-brother Peregrine Smith who worked for him at Sweeney Reed Galleries observed that he was irresponsible with money, with cash going into his pocket. Asking for unpaid salary he was owed, Peregrine was told by Sweeney to take some stock.28

It is all too easy to speculate that something less than conventional may well have occurred when someone of whom such things have been said, is involved in transactions the details of which are at best vague. And this has tended to be the case with Sweeney’s involvement with Marksman – no one knows exactly, and most wonder.

But why should this be?

Absent concrete evidence to the contrary, an alternative straightforward hypothesis is equally valid. Sunday Reed simply gave Marksman to Sweeney. Moreover this sits well with it being on the wall in Heide I in 1969, and also with what can easily be seen as a general antipathy on her part towards this one Kelly not painted with her at Heide – an antipathy best characterised by her refusal to show Marksman with the other Kellys after 1958. And Marksman was not the only Nolan hanging at Heide I during Sweeney’s time there with his family. Pamela speaks of a Nolan in the bedroom.29

Other early Nolans are also known to have gone to McAlpine (and thence back to Nolan) via Sweeney. Jane Clark records an identical devolution for another work in her 1987 Landscape and Legends retrospective, the very first of any Kelly painting: Kelly and Sergeant Kennedy, which is listed as further devolving to “Nolan Gallery, ‘Lanyon’, Department of Territories. Presented by the artist 1974.”30

Another pointer to the likely legitimacy of such transactions is the fact that by 1966 Strines Gallery was operating. Sweeney had just returned from London and it is entirely possible, even likely, that he met Nolan there. Indeed film maker Philippe Mora, closest of friends in Sweeney’s childhood and youth, recalls having it in his head “that Nolan gave Sweeney paintings to sell when he started Strines.”31

It is also on record that in 1968 the Reeds were exploring selling early Nolans including “one of the 30 or so original Ned Kelly paintings – not one of those in the 25 which are held as a unit, but painted at the same time.” It is significant that by March 1968 they did not regard Marksman as one of the core first series. However, regarding Sweeney, in a PS to this letter written to the dealer Kym Bonython , John Reed states “You may wonder why we do not operate in this instance through Sweeney; but I think you will realise that this type of transaction is a bit out of his range, which is mainly in the field of young artists coming up.”32 (My thanks to Kendrah Morgan for drawing this letter to my attention.)

Reed’s assessment of Sweeney’s capabilities, even if accurate in 1968, would soon prove to have sold him short. In October 1972 Sweeney Reed Galleries hosted the successful and critically acclaimed full series of Albert Tucker’s Images of Modern Evil and 18 months later his exhibition 74 Acquisitions would see Vassilieff’s iconic sculpting Stanka Raizen (sic), Nolan’s horizon lifting Kiata (held by John Sinclair) and the first 4×3 Kelly Stringybark Creek (as Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek was then known, and now in the Estate of Clive Turnbull) all go to the Australian National Gallery where Sweeeney had forged a strong connection with its first director James Mollison.33

Sweeney Reed took his life in Les Kossatz’s Carlton studio in March 1979. The covers of the memorial booklet prepared by the Reeds carry two of his visual poems. In hiding, and part obscured, they also touch on the lack of transparency of Marksman’s provenance.

Rear and front cover of memorial booklet for Sweeney Reed 1945 – 1979. Two of his visual poems exhibited at Tolarno Galleries in 1978

Sweeney Reed —> Alistair McAlpine (first possession)

First a little about Alistair McAlpine.

Whichever side of the political or artistic divide one favours, it is difficult to avoid words like remarkable and extraordinary when talking of McAlpine. Born in 1942, he died in january 2014 and his obituaries34 tell of his varied interests and passions. Fourth generation in the Sir Robert McAlpine building and construction dynasty, McAlpine had ample funds to indulge his many enthusiasisms. Indeed in 1989 he was described as one of Europe’s 10 wealthiest men.35

When travelling the world with his parents while still a teenager, he fell in love with Australia in general and Western Australia in particular, and returned to reside and work in Perth and Broome for extended periods, with frequent visits when not in actual residence. He is reported to have spent $500 million in developments in Broome. An avid collector, whilst still in his 20s he had assembled an impeccably chosen selection of contemporary British sculpture, so extensive that he gifted it to the Tate Gallery when it outgrew the grounds of his not insubstantial residence. His collecting extended well beyond art and his extraordinarily eclectic taste can be seen in collections as disparate as police truncheons and exotic breeds of poultry. He also collected personalities – people whom he found appealing – among them Sidney Nolan; another, Margaret Thatcher who asked him to be Treasurer of the Conservative Party when she became leader in 1975. He remained in this position until 1990.

A man of remarkable contradictions, he confessed to being a Labor Republican in Australia although a Conservative Monarchist in the UK.36 Who could imagine a Thatcher insider and devotee (he referred to her as “Your Magnificance”) writing of John Howard being “a man small in stature and with an outlook to match. Thrown into office by the excesses of the Labor government, he had not the first idea what to do with power. … The man is tinkerer.” On the other hand he found Paul Keating “to be both cultured and a visionary: a man deeply interested in the wider stage. … His reforms have been neutered by John Howard, a man whose very life’s work is in finding ways of not doing things or in undoing those things that others have done.”37 Having extraordinary political influence, McAlpine may well have played no small part in Nolan’s 1981 British knighthood and his Order of Merit in 1983. His influence had obviously waned by the time John Howard received his OM in 2012.

It appears possible, indeed probable, that McAlpine derived title in Marksman, not from Sweeney Reed, but from Julian Sterling of Southern Cross Galleries. McAlpine writes of Sterling: “over the first five years of the 1970s, I bought from him a number of Sidney Nolan’s early works, among them The Dog and Duck Hotel, …. Burke dying under a tree, the deserted mine, and a policeman with his head down a wombat hole. Along with these paintings, I also bought First Class Marksman.“38

Julian Sterling died in 2012. A report of his death in the Financial Review records that he “cherry-picked the best Australian artworks to buy and sell as the market was on the way up. Great paintings including Russell Drysdale’s The Cricketers and Sidney Nolan’s Dog and Duck Hotel set benchmark prices for Australian art when Sterling sold them. … he offered those who brought the most desirable artworks to him for sale an attractive, often cash deal. He left his runners – people such as Sweeney Reed … good margins, placing their finds with the nouveau rich, who were only just beginning to trophy collect. … He sold many major works from the Heide circle through Reed …”39

A more recent article states “In Melbourne, there has probably never been a collector like Julian Sterling. In a literal sense, Sterling was the ultimate wheeler dealer – it was by trading art and cars that he made his fortune.”40

Several newspaper reports of the 1960s and 1970s link McAlpine, who had been buying early Kellys in 1965 when all of 23 years of age, to both Nolan and Sterling. In 1966, The Age, when reporting the purchase by McAlpine of Drysdale’s Cricketers for the then record Drysdale price of £16000, stated “Two weeks ago the painting was bought, for an undisclosed sum, by the Southern Cross Galleries. The gallery proprietor, Mr Julian Sterling, said yesterday he knew it might be for sale. … Mr McAlpine paid £2200 for a Nolan of the Ned Kelly series three months ago.”41 The Australian Financial Review in 1972 reported that McAlpine “was reputedly buying all the good early Nolans he could. Mr McAlpine is a friend of Nolan and has apparently always been keenly interested in his work. Early Nolans, unlike his later works, are not easy to purchase in London.”42

The timing of McAlpine’s purchase is uncertain. If, as seems likely, Julian Sterling was an actual title holder, his would only have been a transitory holding. The transfer to McAlpine must have been later than 1969 when the work was photographed on the wall at Heide I, and earlier than 1976 when, almost certainly in Nolan’s possession, it was exhibited in the Sidney Nolan exhibition at Moderna Museet Stockholm.

Alistair McAlpine (1st possession) —> Sidney Nolan

Whether McAlpine sold to Nolan himself or to the Sidney Nolan Trust is a matter of some conjecture, with the answer most likely to be found within the so-called “Cynthia Nolan Papers” which include many of Sidney Nolan’s own papers and records, as well as Cynthia’s.43

McAlpine has written “I was somewhat perverse in my dealings with Sidney Nolan, for I used to buy his early works in Australia, the ones that everyone wanted and, and swap them with him for his later paintings …. Sidney needed his earlier work, first as a reference to move forward, and then to give to the art gallery at Lanyon near Canberra.”44

It is unclear how long Marksman remained in McAlpine’s possession. A line can be taken from other 1940s paintings owned by Nolan himself and in his European exhibitions at this time. A case in point is the 1947 painting Mrs Fraser, in Nolan’s possession from at least 1957 and exhibited without Marksman at Dublin and Zurich in 1973, and then exhibited with Marksman at Stockholm in 1976. This suggests that Nolan acquired Marksman from McAlpine between 1973 and 1976.

It would remain with him until 1989.

1989, Sidney Nolan Trust —> Alistair McAlpine (2nd posession) and Waddington Galleries

Nolan finally parted company with Marksman, only three years before his death, when it went under the hammer on 14 August 1989 as lot 296A in Sotheby’s Melbourne auction. Whether the vendor was Nolan himself or his Trust is a matter of some conjecture. While making no reference to provenance as such, the auction catalogue certainly lists the vendor as being the Sir Sidney Nolan Trust. This also accords with a passage in McAlpine’s Bagman to Swagman suggesting that towards the end of his life Nolan was in need of cash. Speaking of Nolan’s final years, McAlpine writes “Faced with problems from British Internal Revenue – Sidney had only the vaguest notion that sometimes you had to pay tax – he went into a decline.”45

A newspaper report the next day quoted Sotheby’s as saying that the painting “was sold for $825,000 at auction last night” but that they “could give no information about the buyer.” The price was reported to be a record for a living Australian artist.46 In advance of Marksman’s final auction in 2010 the Herald Sun reported that McAlpine bought it back for $825,000 at Sotheby’s in Melbourne in 1989.47

However Lauraine Diggins, whose Fine Art establishment is noted in the Menzies Press Release provenance chain in these terms: “Alistair McAlpine, United Kingdom, (acquired through Lauraine Diggins Fine Art, Melbourne),” has advised “this may not be the case, it might have been Sidney Nolan direct and most likely was.”48 Her further advice is that Marksman was passed in at the auction, then sold immediately after to Waddington Galleries of London, acting on behalf of Alistair McAlpine. From her records, she believes that Waddington & McAlpine owned the painting jointly.49 The painting returned to London.

1991, Alistair McAlpine (2nd possession) and Waddington Galleries —> Stephen Vizard

The Herald Sun report prior to the 2010 auction suggests that by 1991 McAlpine too was becoming cash-strapped: “Bad times saw Alistair McAlpine sell it to Steve Vizard, who became chairman of the NGV.” Both the Menzies 2010 auction catalogue and the provenance listing in the advance Menzies Press Release indicate that title passed from McAlpine to the Vizard Foundation, however in the Press Release narrative it is clear that the sale was to Steve Vizard personally. This accords with my advice that in 1991 McAlpine and Waddington consigned Marksman from London to Lauraine Diggins Fine Art50 to whom an offer was made by Ian Rogers on behalf of Steve Vizard which McAlpine refused. Vizard then went to Sotheby’s through Ian Rogers and a further offer was made which was accepted.51

1992, Stephen Vizard —> Vizard Foundation

In 1992 Vizard became chairman of NGV. As stated in the 2010 Menzies Press Release: “First Class Marksman was acquired by the Vizard Foundation as a donation from Mr Stephen Vizard in 1992. It has since been on permanent display at the National Gallery of Victoria.”

2010, Vizard Foundation —> Gleeson-O’Keefe Foundation —> Art Gallery of New South Wales

First Class Marksman went under the hammer again as Lot 51 at a Menzies auction of Australian, aboriginal & international fine art in Sydney on 25 March 2010 – 62 years to the day from when, and near enough to 6.2 kilometres from where, Nolan married John Reed’s sister Cynthia in 1948.

In hindsight the result can be seen as a marketing triumph par excellence. Not for the first time did First Class Marksman take good aim. Within the week it was revealed that AGNSW had acquired the painting, “bought last week with money from the estate of Australia’s leading surrealist artist James Gleeson and his partner Frank O’Keefe.”52

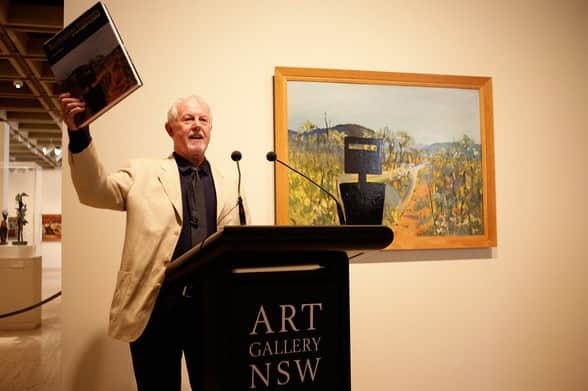

Lou Klepac, Chairman of The Gleeson O’Keefe Foundation, addresses the audience as Australian painter Sidney Nolan’s ‘First Class Marksman’ is unveilled as the newest acquisition by the Art Gallery of New South Wales on March 31, 2010 (Brendon Thorne/Getty Images)

A few days later, a report in the Sydney Morning Herald53 told of a secret meeting in the office of AGNSW director Edmund Capon, who had coveted the work for ten years and had been discussing its purchase with Vizard for five. His interest was well known to the vendor, as was that of the National Gallery of Australia. NGA held the other 26 first series Kellys, and revealed on the day after the auction how it had failed in its attempt to secure the artwork before auction.54

Quoting from this SMH report: “The meeting was a closely guarded secret. No one in the room wanted word leaking of what they were planning. ….”

“Seated around the table in the director’s office were the writer Lou Klepac, the former banker Michael Gleeson-White and the collector Ray Wilson. The men oversee the $16 million Gleeson O’Keefe Foundation … The meeting was to decide strategy and how much they were prepared to pay. … At the close of last Tuesday’s meeting, agreement had been reached to bid on the work, … and a price limit had been set – of $5.4 million.”

“But Capon wanted more: a guarantee in writing that up to $5.4 million would be paid. Klepac agreed on one condition. ”I said, ‘If you get the picture, I want the letter back’,” Mr Klepac said. ”I am going to frame it.” He handwrote the letter the next day and rushed it off to Capon.”

And so to bid – as a Kiwi Pepys is wont to exclaim.

The SMH report continues: “Bidding began at $3 million. There were just two bidders. One was the Art Gallery of NSW. The other is unknown. It was not the National Gallery of Australia … The bids increased in increments of up to $300,000 … The hammer fell at $4.5 million which, when the buyer’s premium was added, took the price to $5.4 million, a record for an Australian painting at auction.”

“Remarkably, it was the amount agreed in Klepac’s letter. ‘It was a crazy coincidence,’ he said. ‘I think it was meant to be. The gods helped.’ ”

Indeed.

The report concludes “Klepac has reclaimed his $5.4 million letter.”

Undoubtedly it has been well framed.

Conclusion

And so concludes this pot shot at the provenance of Sidney Nolan’s First Class Marksman.

It is perhaps not entirely unfitting that the subject of such a quest, pursued as it has been through such a tangled web, should be a Janus-faced bushranger! Nor perhaps is it inappropriate that Marksman does not rest with the other first series Kellys at NGA. It remains what it has always been – the outlier among them; logistically, since 1958, and stylistically, from the day it was painted.

One final speculation. It is quite possible the Kelly painting John Reed contemplated selling in his letter to Kim Bonython in 1968 – “one of the 30 or so original Ned Kelly paintings – not one of those in the 25 which are held as a unit, but painted at the same time” – is today’s $5,400,000 Marksman. Reed’s letter continued “and the figure we had fixed was $8000.”55 (This would represent a compound growth rate of 10% above inflation.)

Several things clearly remain uncertain regarding the provenance, and I welcome contact from any reader in possession of information which can update this article.

A number of forthcoming publications may well reveal more. Two biographies are due in early 2015: one on Nolan by Nancy Underhill, another on John and Sunday Reed by Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan. October 2014 will see the launch of a book by Barry Pearce, now Emeritus Curator of Australian Art at AGNSW who curated the 2007 Nolan Retrospective. Entitled 100 moments in Australian painting, its cover illustration is Marksman, suggesting that something connected with the painting may well be one of those moments.

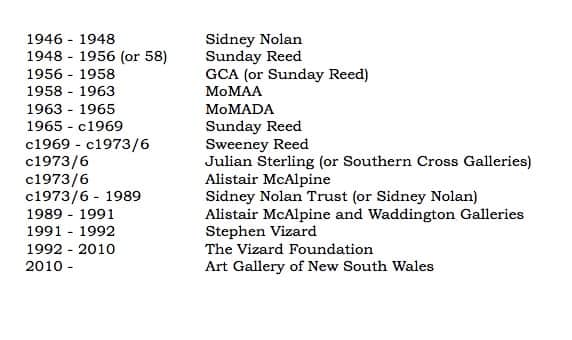

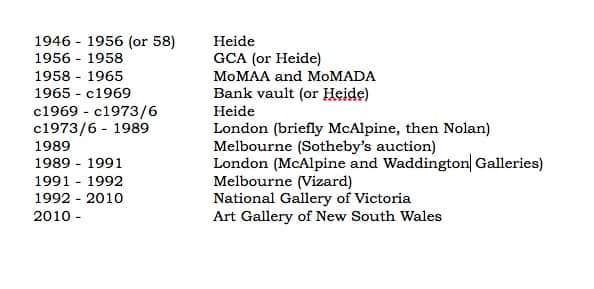

Chronological listings follow. First, of all those who are known, or who are likely, to have held title to Marksman; and second, of all known, or likely, locations of the painting.

Chronological listing of those having, or likely having, title to “First Class Marksman”

Chronological listing of locations, or likely locations, of “First Class Marksman”

ENDNOTES

- It was painted at Danila Vassilieff’s house Stonygrad in Warrandyte.

- It is now in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- Felicity St John Moore, Vassilieff and his Art, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2012, p. 190. Felicity Moore says that the trigger for Nolan’s pivotal ‘dead-eye’ in Marksman was the Petrouchka puppet’s ‘dead-eye’ in the Dance rehearsal scene located on the reverse, upside down, of Vassilieff’s Expulsion from Paradise screen, 1940, NGA collection. (Email to the author, 13 November 2014.) See also endnote 6.

- It sold at auction on 25 March 2010 for $5.4 million.

- In 2003 the Supreme Court of Victoria considered the disputed ownership of three Sidney Nolan paintings. The decision, Nolan v Nolan (2003) VSC 121, discusses the question of gifts (paragraphs 121-131, wherein limitation of actions legislation is outlined in paragraph 127), and interestingly in terms of the present essay, considers the extent to which reliability can be placed on provenance as listed in catalogues (paragraphs 196-206).

- See also endnote 3. Felicity Moore advises that Nolan told her Marksman was pivotal in a phone conversation in 1977. (Conversation with the author on 7 November 2014). Her article From Vassilieff to Nolan: The secret of the Kelly series strongly links Nolan’s first Kelly works to Vassilieff and argues the imagery in the 1940 Iconostasis painted by Vassilieff, and which Nolan would have seen at Stonygrad, triggered Marksman and also Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly which was painted in October 1946. The article also elaborates on the significance of “pivoting dead/double eyes” in Marksman. Rather than attempting to selectively quote from or paraphrase the article, this link is provided to its first publication in The Ballets Russes in Australia and Beyond, ed. Mark Carroll, Wakefield Press, Adelaide 2011, p. 129 and in particular from p. 135. Barry Pearce says this article reveals “a fascinating discovery riddled with complexity.” (See Barry Pearce, “Cossack to the core”, The Weekend Australian, 8-9 September 2012, p. 58.) Pearce adds “but there are other secrets and connections yet to be explored regarding those Kelly pictures. But that is another story.” An article The True Inner History of the Kelly Gang , which explores Nolan’s Kelly paintings further and may well find another story, is currently in preparation and scheduled to be posted on this website in Autumn 2015.

- Sidney Nolan, Letters to John Reed, Papers of John & Sunday Reed, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, Box 2, File 6.

- On 19 January 1948 he wrote to Albert Tucker in London giving his address as c/o Heide, thus suggesting that only two months before he married John Reed’s sister Cynthia he thought to return to Melbourne. (Patrick McCaughey, Bert & Ned, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, p. 77).

- This letter was dated 26 February 1948. See Warwick Reeder, The Ned Kelly Paintings: Nolan at Heide 1946-47, Museum of Modern Art Heide, Melbourne, 1997, Endnote 2, p. 14.

- A comprehensive account of the Reeds’ involvement with GCA and subsequently with MoMAA and MoMADA can be seen in the chapter entitled “Now We’ve Got Our Gallery,” (Janine Bourke, The Heart Garden, Random House, Sydney, 2004, p. 336).

- Barrett Reid and Nancy Underhill, Eds., Letters of John Reed, Viking, Melbourne, 2001, footnote 3 on p. 30.

- The Ned Kelly Paintings: Nolan at Heide 1946-47, op. cit., p. 9.

- Warwick Reeder, The First Real Collection of Australian Contemporary Art?, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2005.

- Marksman’s exhibition with MoMAA in 1958 would be its last for almost 20 years. It would not be hung in a public gallery again until 17 January – 7 March 1976, when, most likely in the possession of the artist, it appeared in the Sidney Nolan exhibition at Moderna Museet Stockholm.

- Warwick Reeder, The Ned Kelly Paintings: Nolan at Heide 1946-47, op. cit., p. 9.

- Janine Burke, Heart Garden, op. cit., p. 351. Burke says this occurred “prior to the 1964 London show” and it is not entirely clear whether this restoration by Williams was in fact the cleaning and varnishing referred to in the 1963 George’s Gallery catalogue as mentioned by Reeder (The Ned Kelly Paintings, op. cit., p. 9.) It likely was, for it seems improbable they would have been ‘restored’ so soon after having been cleaned and varnished.

- John Reed, letter to Kym Bonython, 22 March 1968, Reed papers, State Library of Victoria, MS 13186, box 3a, file 1.

- Warwick Reeder, The First Real Collection of Australian Contemporary Art?, op. cit.

- Janine Burke, Heart Garden, op. cit., p. 352.

- Sidney Nolan, Paradise Garden, R. Alistair McAlpine Publishing Ltd, London, 1971, p. 53.

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan: Landscape and Legends, A Retrospective Exhibition 1937-1987, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, 1987, footnote 14, p. 73.

- Jane Clark, email to the author, 10 November, 2013.

- Richard Haese, Permanent Revolution: Mike Brown and the Australian avant-garde 1953-1997, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2012, p. 165.

- Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Sunday’s Kitchen: Food & Living at Heide, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2010, p. xxxiii.

- Sterling’s involvement lasted only six months. In April 1974 John Reed wrote to Gray Smith that Sweeney’s new gallery had been “built on the basis of him having a senior partner (Julian Sterling) who was not only very experienced and shrewd (too shrewd) but also financially secure…. Julian withdrew after only 6 months ….” See Reid and Underhill, Letters of John Reed, op. cit., p. 790.

- Informative cameos on Sweeney Reed can be found in Harding and Morgan, Sunday’s Kitchen, op. cit., p. 171; and Reid and Underhill, Letters of John Reed, op. cit., p. 401. For a more detailed account see the chapter entitled “Sweeney’ in Janine Burke, Australian Gothic; A Life of Albert Tucker, Random House, Sydney, 2002, p. 382.

- Barrett Reid, A Farewell for Sweeney, spoken at his funeral service on 31 March 1979.

- Janine Burke, The Heart Garden, op. cit., p. 410.

- Janine Burke, Australian Gothic; A Life of Albert Tucker, op. cit., p. 391.

- Jane Clarke, Landscape and Legends, op. cit., p.76.

- Philippe Mora, email to the author, 30 September 2014.

- John Reed, letter to Kym Bonython, 22 March 1968, Reed papers, op. cit.

- 74 Acquisitions, Sweeney Reed Galleries, Melbourne, 1974.

- Here are links to obituaries: The Guardian, The Independant, The Telegraph and BBC News.

- Sydney Sun-Herald, 21 May 1989, p. 3.

- Alistair McAlpine, Once a Jolly Bagman, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1997, p. 174.

- Alistair McAlpine, Adventures of a Collector, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2002, p. 25-26. His opinion of Howard is measured in that it was written five years after this earlier more charitable assessment: “A thoughtful, sincere man, he has none of the flash and sparkle of Paul Keating, but in his determined way he will be a good and possibly a great Prime Minister of Australia.”(Once a Jolly Bagman, op. cit., p. 177).

- Alistair McAlpine, Bagman to Swagman, Allen & Unwin, London, 1999, p. 233.

- Terry Ingram, “Winner of many battles,” Financial Review, Sydney, 14 June 2012.

- Mark Hawthorne, “How stamps tore a family apart,” The Age, Melbourne, 8 August 2014.

- The Age, Melbourne, 17 February 1966.

- Australian Financial Review, Sydney, 16 November 1972.

- The papers are held under lock and key at the National Library of Australia where their very existence is not to be found in the online catalogue or in the list of holdings of the Manuscripts Collection. Enquiries reveal the papers are not accessible until 2020-2021, 45 years from their receipt by NLA in 1975 and 1976. The collection appears to have been accessed only once, in quest of evidence in connection with a court battle between Nolan’s widow Lady Mary Nolan and his step-daughter Jinx, Cynthia’s daughter, concerning ownership of three Nolan paintings. The 2003 decision of the Victorian Supreme Court (Nolan v Nolan (2003) VSC 121) chronicles in paragraph 168 an hilarious account of the collection in London of some of the papers, in manner avoiding Nolan himself, by the NLA representative who reported: “I shall be grateful if you will send another letter of thanks to Mrs Nolan when you receive these papers. Mrs Nolan would prefer that we did not call this gift simply `the Nolan papers’. She said that it includes her own literary manuscripts. Further, if it were not for her, her husband would not be as famous as he is today, nor would the National Library ever have acquired the papers. She proposed therefore that the gift be named after herself. I did not catch all her names. … Perhaps in your letter to her you could refer to them as the Cynthia Nolan Papers. Mrs Nolan does enjoy a certain reputation for eccentricity. Her husband knows she is transferring papers to the library, but she does not want him to see documents leaving the house. She therefore asked me to call at a time when he was out. After putting the cartons into the car I was sitting in the kitchen taking tea with her. A footstep was heard on the stairs. Mrs Nolan flew out to intercept her husband, explained loudly that she was having a cup of tea with someone she had picked up in the park, and persuaded him to continue on his way upstairs. Back in the kitchen she thrust my overcoat into my hands, whispered `I’m always picking up people in the park’ and turned me out of the house. I felt as if I was playing a scene from a farce by Feydeau”.

- Alistair McAlpine, Bagman to Swagman, op. cit., p. 238.

- ibid., p. 241.

- Canberra Times, 15 August 1989, p. 2.

- Peter Coster, “Sydney (sic) Nolan painting of Ned Kelly expected to set Australian record at auction“, Herald Sun, Melbourne, 16 February 2010.

- Lauraine Diggins, email to the author, 29 September 2014.

- Lauraine Diggins, email to the author, 18 October 2014.

- McAlpine has written: “Lauraine Diggins was another dealer from whom I bought some wonderful paintings. Imaginative and energetic, she always seemed to be able to lay her hands on just the right sort of paintings, a talent displayed by few in her trade.” see From Bagman to Swagman, op. cit., p. 234.

- Lauraine Diggins, email to the author, 18 October 2014.

- “AGNSW reveals mystery buyer of Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly,” The Australian, Sydney, 31 March 2010.

- Joyce Morgan, “How the Ned was won,” Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 2 April, 2010.

- “AGNSW reveals mystery buyer of Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly,” The Australian, Sydney, 31 March 2010.

- John Reed, letter to Kym Bonython, 22 March 1968, Reed papers, op. cit.

2 Comments

Join the conversation and post a comment.

kelly at the mine, is also from the first series and not in the NGA collection, it is at Heide

Yes. I’m afraid the expression “first series” is, like Marksman’s provenance, a little imprecise. As I later mention, I’m referring to the twenty-seven 4′ x 3′ paintings selected by Nolan for inclusion in the first hang of the Kellys in 1948 at Velasquez Galleries. As well as Heide’s “Kelly at the Mine”, there are a number of other 4x3s painted up to 1947 including four at CMAG: “Kelly and Horse”, “Policeman in Wombat Hole”, “Return to Glenrowan”, “Kelly”; also Westpac’s “Ned Kelly at Glenrowan”. And there are also quite a few earlier Kellys in the smaller 2′ x 2’6″ format.