An introduction by David Rainey.

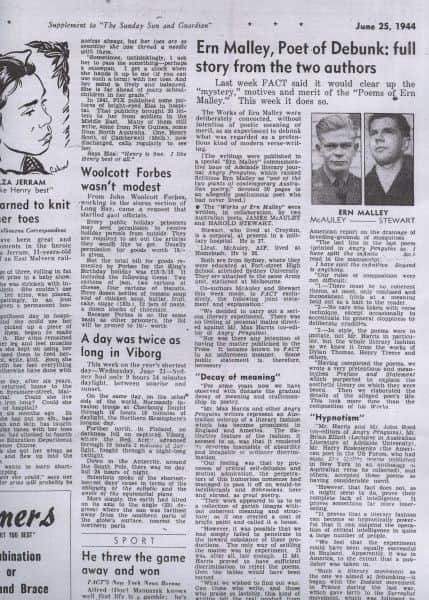

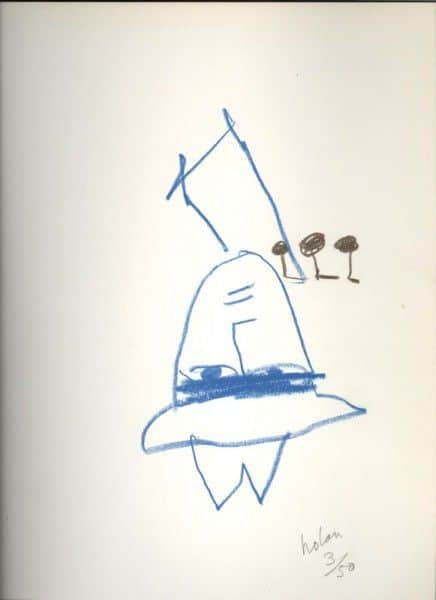

Sidney Nolan, “Ern Malley”, crayon drawing on frontispiece of “The Darkening Ecliptic”, McAlpine, London, 1974.

One Saturday afternoon in October 1943, two young Sydney poets on war service in Melbourne found themselves at Victoria Barracks with time on their hands. Lieutenant James McAuley and Corporal Harold Stewart held rhyme and metre somewhat sacred and wrote verse more traditional and classic in style than that of modernists of the period like Dylan Thomas, Henry Treece and T S Eliot and their Australian champions such as Adelaide poet Max Harris. However, that October afternoon McAuley and Stewart composed an anthology of modernist-style poems for despatch to Harris, who with John Reed edited Angry Penguins, a little magazine which published avant-garde literature and art. Opulent by the standards of the day, Angry Penguins was the bane of the culturally conservative.

Some years younger than McAuley and Stewart and full of unbridled enthusiasm, Harris was only nineteen when he helped establish Angry Penguins in 1940. Three years later he met Reed and his wife Sunday and became part of the circle at Heide, where the Reeds dispensed largesse, sustenance and encouragement to a group of artists and literati that included Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester, John Perceval and Arthur Boyd. Harris, already with two collections of published poems to his name and opinions readily aired, was seen by the two Sydney poets as well deserving of a fall from what they saw as his modernist high horse.

The poems they wrote that afternoon were an amazing collection. Interspersed with verses they had already worked at over the years were new compositions of varying degrees of obscurity. Together the poems formed an eclectic pastiche ofShakespeare, Mallarmé, Purcell, T S Eliot and Keats – to name a few sources; they also used a rhyming dictionary, the Oxford Dictionary, a dictionary of quotations and anything else at hand, even a US Army report on mosquito control and earlier works in Angry Penguins itself. From these ingredients, in the crucible of their own quite formidable poetic talents, they forged the modernist parody they would later describe as ‘deliberately concocted nonsense … utterly devoid of literary merit as poetry’. 1

Nor did their creativity end with their verse. Stewart and McAuley also invented a poet, Ernest Lalor Malley, into whom they breathed this life. Born in England in 1918, he came to Australia after his father died in 1920 from war wounds. The family lived in Petersham and Ern went to the Petersham Public School and Summer Hill Intermediate High. He did poorly at school and when in 1933 his mother died, left to work as a mechanic in Palmer’s Garage on Taverner’s Hill. He went to Melbourne in 1935 where he lived in a room by himself, sold insurance policies, and was fond of a girl but had some difference with her. In 1940 he was making money repairing watches and doing other work on the side. By the beginning of 1943 he was back in Sydney where he passed away from Graves Disease. He was cremated at Rookwood.2

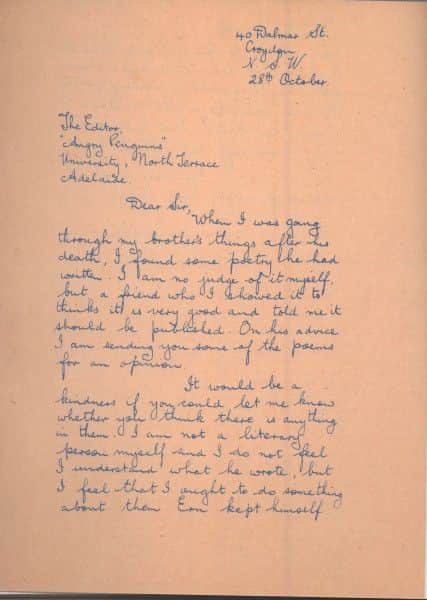

The hoaxers’ final invention was Ern’s sister Ethel, who supposedly found Ern’s verse beneath his deathbed and sent it to Max Harris for an opinion. Her first letter enclosed only a few of the poems and these astonished Harris. How could a poet capable of such work be unknown? The trap was set and baited; it remained only for Harris to be ensnared.

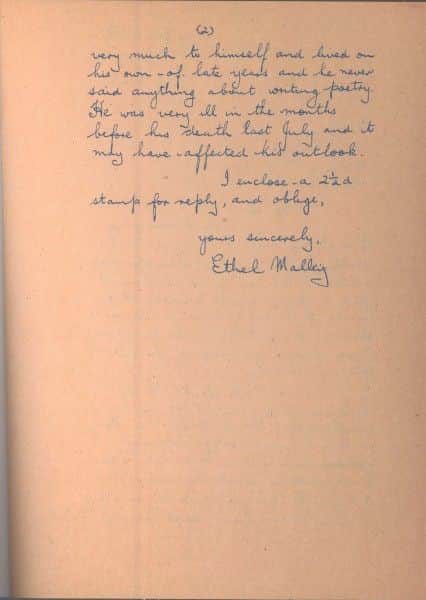

Harris sent the poems post-haste to John Reed and replied to Ethel who soon despatched the remaining poems. Collectively called The Darkening Ecliptic, they arrived with Ethel’s lengthy account of her brother’s short life which had ended on 23 July 1943 at that most Keatsean of ages, just twenty-five. They were published in early June 1944 in an Angry Penguins number boasting a brilliant coloured cover of a Nolan painting, Sole Arabian Tree. The introduction by Harris eulogised Malley as one of ‘two giants of contemporary Australian poetry’. 3

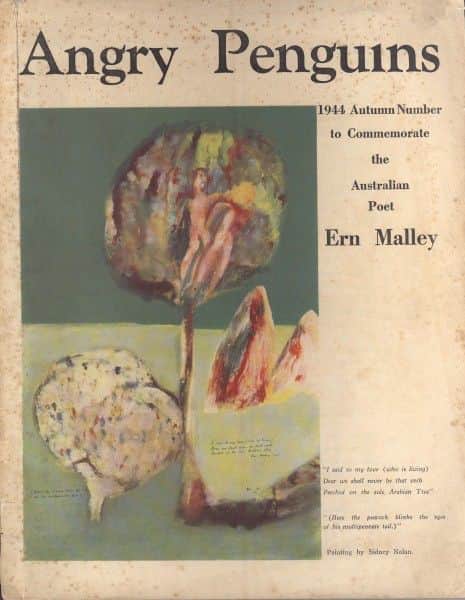

The bubble burst in just three weeks. On 25 June 1944 in Fact, the magazine supplement to Sydney’s Sunday Sun, McAuley and Stewart took responsibility for what they called ‘a serious literary experiment’. 4 Within days it became a sensation in the local press, and was soon international news in reputable papers such as the London Times and magazines like Time and Newsweek. In a war-weary world what could be better than a good story deflating a group of pretentious intellectuals! And to be sure the lesson was well learned: within three months Max Harris had been prosecuted, put on trial in Adelaide, convicted and fined for publishing an ‘indecent advertisement’.

Australian modernism was on trial again. When the award of the 1943 Archibald Prize to William Dobell had been challenged as not being a true ‘portrait’, it was really the painting itself in the dock. Similarly, Harris’s trial was de facto of the poetry itself. The hoaxers had certainly not intended this. Harold Stewart would first read the transcript of the Harris trial forty-five years later and observe it to be ‘sheer incredible black farce. The law succeeded in proving itself an ass (in the American sense also) twice during this anus mirabilis, what with Dobell and Max.’ 5

The debate as to the merit of the Ern Malley poems has ebbed and flowed ever since. Are they good or bad? Did the McAuley/Stewart collective muse transcend their intent merely to hoax Harris and end up producing work of real merit? More recently, with all three now deceased, the question has been ‘will the poems outlast them all?’ This thought had plagued the hoaxers themselves for years as they worried they were becoming better known for the hoax than for their own verse. Worse still was the prospect that the merit of the Malley poems could eclipse that of their own. A darkening ecliptic indeed!

That prospect becomes more a reality as time passes, and today the name Ern Malley is better known than ever. A Google search for the expression ‘the poet Ern Malley’ returns more hits than do similar searches for McAuley or Stewart, and a search for the title Darkening Ecliptic returns twice as many hits as does one for McAuley’s first book Under Aldebaran or Stewart’s first book Phoenix Wings.

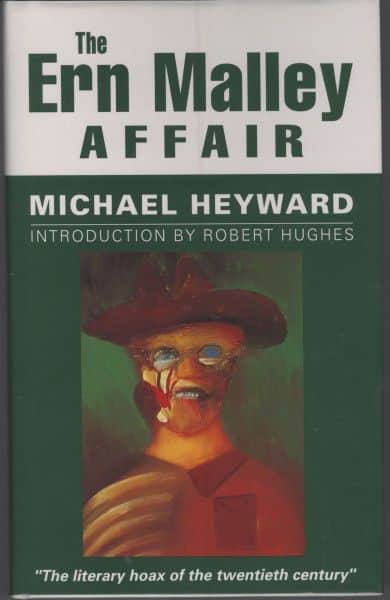

None of this is surprising once we look at the mountain of artistic endeavour inspired by the poems and by the story. What other Australian poet has so galvanised the national muse and generated an interest and fascination resulting in a seemingly never-ending litany of works in their praise or in recognition of their place in our culture? Ern Malley can lay claim to plays, a musical, films, an Ern Malley Journal, academic theses, countless articles, Michael Heyward’s ‘biography’ The Ern Malley Affair, a reincarnation in Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake, a rock band, musical settings, a jazz suite, a recitation by Orson Welles, websites, and radio and TV documentaries. His poems have been republished in their entirety a dozen times and partially on several occasions – not only in Australia but London, Paris, Kyoto, New York and Los Angeles. Most amazingly of all, there are literally hundreds of Malley-inspired works of art by a dozen or so artists, starting with Sidney Nolan in 1943.

Sidney Nolan, Crayon sketch of Ern Malley on frontis piece of 3/50 lim. ed., ‘The Darkening Ecliptic’, McAlpine, London, 1974.

Nolan alone produced more than a hundred Malley images, including ’portraits’ of this poet who never existed. Indeed the effect of the Malley poems on Nolan cannot be overestimated and on more than one occasion he said that without Ern Malley there could have been no Ned Kelly in his work. His Malley oeuvre culminated with a monumental Ern Malley and Paradise Garden exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia for the 1974 Adelaide Festival. In 2009 the exhibition Ern Malley: the Hoax and Beyond was held at the Heide Museum of Modern Art.

The effect of the whole saga on the main protagonists, indeed on modernism in Australia, has been both profound and lasting. It is perhaps ironical that as Australian painters of more modernist disposition went from strength to strength in Malley’s wake, the lot of our modernist poets waned. A reason often advanced for this is that whilst the ensuing brouhaha thrust the painters into a spotlight from which they blossomed, the poets retreated, fearing they would be lumped in with those who were, in the words of the hoaxers, ‘insensible of absurdity and incapable of ordinary discrimination.’ 6 A less subtle reason may be the generally higher calibre of modernist art being produced at the time compared to modernist verse.

The personal lives of the hoaxers, of Harris, even of Nolan, also suffered. Less so Nolan, who simply embraced the poems as real, meaningful and of great significance, even prescience, to his life at Heide and later. In an interview not long before he died in 1992 he spoke of how the hoaxers’ ‘only mistake is to persist that it was nonsense. It wasn’t.’ 7

Max Harris seems to have suffered most. In a wide ranging interview on ABC radio in 1969 which featured almost all the personalities involved he spoke about the hoax, his trial and its aftermath: ‘It was bad enough to have been the victim of a hugely successful and cunningly organized hoax, but thereafter to be attacked by society in the large for having been the victim of the joke, could be extremely damaging.’ 8 None of his verse was published after Angry Penguins until The Coorong and Other Poems appeared in 1955. He went on to become a prominent publisher and book shop owner, man of letters, columnist and critic. Harris never wavered on the question of Ern Malley: ‘I am frequently asked whether with hindsight I regret being the gullible victim of the Ern Malley events. My answer? What do you think?’ 9 He maintained an admirable objectivity when looking back on the Malley years, even conceding that McAuley’s ‘1944 manifesto was only intended, I should imagine, as a corrective to the excesses of the time, excesses for which I must accept a great deal of the blame.’ 10

James McAuley would become one of the most prominent public intellectuals of his day: a New Guinea expert, foundation editor of the conservative journal Quadrant, cold war warrior, ardent and devout convert to Catholicism, Professor of English at Tasmania University, authority on Blake, Brennan, Trakl and Rilke, and writer of memorable hymns. When he died in 1976 he was regarded as one of our foremost poets.

After the hoax Harold Stewart largely withdrew from public view. His interest in Eastern religion and culture saw him visit Japan in 1961, 1963, and again in 1966 never to return to Australia. He settled in Kyoto and it was here that his literary output truly flourished alongside an extraordinary scholarship and knowledge of Buddhist teaching – he was a devotee and scholar of Pure Land Buddhism and trained for but declined ordination to the priesthood. At the time of his death in 1995, just six months after Max Harris, he was among the most respected western authorities on the writings of the Pure Land branch of Shingon.

Paradoxically, as the main players now begin to show signs of fading into history, the interest in Ern himself refuses to abate. As Michael Heyward summed it up in 2005 in the introduction to the 2nd edition of The Ern Malley Affair: ‘He is like one of those minor characters in Shakespeare who gets a handful of lines but continues to glow in the mind.’ 11

Some of the many faces of Ern (l. to r. James McAuley by Ern Malley, Harold Stewart by Ern Malley, Ern Malley by Justin Gill, Ern Malley by Sidney Nolan, Ern Malley by Peter Fay, Ern Malley by Emma Kidd, Sidney Malley by David Rainey)

Some useful Malley references:

By far the most accessible account of the hoax is Michael Heyward’s eminently readable The Ern Malley Affair. 12 Well written and well researched, it reads as fresh and as captivating today as it did when first published almost 20 years ago. Perusal of Heyward’s Ern Malley papers in the State Library of Victoria reveals just how much he must have lived and breathed Malley to the exclusion of almost all else. 13

Another very useful reference site is Issue 17 of John Tranter’s ezine Jacket, 14 where the poems can be read along with transcripts of the trial of Max Harris. This site also contains historic photos.

An Ern Malley website is maintained by Max Harris’s daughter Samela Harris. 15

The catalogue essay for the 2009 Heide exhibition Ern Malley: The Hoax and Beyond looks in some detail at the hoax itself, the brief quest to discover who wrote the poems, the trial, the aftermath, later publications of the poems, derivative works, and the links between Malley and Nolan. 16 It is planned to post this essay on aCOMMENT.

Philip Mead’s book Networked Language examines poetic language in the context of its culture and history and has a chapter “Poetry and the police” dedicated to a critical analysis of some of the Malley poems in the context of the trial of Max Harris. 17

- Fact, magazine supplement to Sunday Sun, Sydney, 25 June 1944, p. 4.

- This biographical outline is abridged from details in letters from ‘Ethel Malley’ sent to Harris by Stewart and McAuley. Coincidently, this Introduction is posted on the 68th anniversary of his demise on 23 July 1943.

- Angry Penguins, no. 6, Reed & Harris, Melbourne, June 1944, p. 5. The other ‘giant’ was Donald Bevis Kerr, co-editor with Harris of the first edition of Angry Penguins in 1940. Kerr was killed in New Guinea when flying supplies over Kokoda in December 1942.

- Fact, op. cit., p.4.

- Harold Stewart, letter to Michael Heyward, 15 November 1992, papers of Michael Heyward, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, PA 96/159, box 6.

- Fact, op. cit., p. 4.

- Sidney Nolan, Interview Michael Heyward, 5 April 1991, Papers of Michael Heyward, op. cit., Box 5

- Max Harris, The Ern Malley Story, ABC radio documentary by John Thomson, 1959; transcript in Clement Semmler, For the Uncanny Man, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1963, p. 171

- Max Harris, ‘Forty four years on’, Ern Malley, the Poems, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988.

- Max Harris, ‘Conflicts in Australian Intellectual Life’, Ed. Clement Semmler & Derek Whitelock, Literary Australia,Cheshire, Melbourne, 1966, p. 29.

- Michael Heyward, The Ern Malley Affair, rev. ed., Vintage, Sydney, 2003, p xxii.

- Michael Heyward, The Ern Malley Affair, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1993, p. 111.

- Papers of Michael Heyward, Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria, PA 96/159

- http://jacketmagazine.com/17/ern-dl.html

- www.ernmalley.com

- David Rainey, Ern Malley: The Hoax and Beyond, exh. cat., Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2009.

- Philip Mead, Networked Language, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2008, p. 87 – 185.