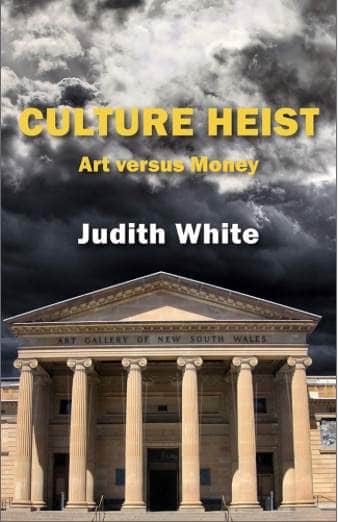

I first saw a photo of the classical revival built courthouse in Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland some years ago when researching the convict John Graham.1 Since then I’ve entered the Art Gallery of New South Wales many times without realising just how closely its portico and pediment resemble the facade of the imposing Dundalk Courthouse. This marked resemblance first struck me on seeing the ominous cover of Judith White’s book Culture Heist, just published by Brandl & Schlesinger.

Courthouse, Dundalk, Co. Louth, 1819

On reading the book, I noted a further resemblance. At the Dundalk Assizes in 1824 John Graham was sentenced to 7 years transportation for the theft of not quite 3 kilograms of hemp. A small heist. Two hundred years on, White speaks with an insider’s knowledge of a potentially far larger ‘heist’ within AGNSW’s classical revival walls, which stand on the very ground John Graham most likely trod.

The long-serving and well liked director of AGNSW, Edmund Capon, retired in 2012 and was replaced by Dr Michael Brand. Dr Brand came to AGNSW well credentialed and highly anticipated. It is regrettable, for all concerned, that the ensuing five years has seen the growth of a divide at the Gallery characterised by frustration, fear, division and dissension. White’s book chronicles these years, set against a background of gallery history, from the viewpoint of one side of the divide – she was executive director of the Art Gallery Society of NSW for terms totalling 10 years, most recently in 2015. It tells of enforced redundancies and summary dismissals of many senior experienced curators, of the removal of the media and marketing team, and of an influx of large numbers of new managers with big salaries and little or no experience in the Arts/Museum sector.

It tells of the new management’s attempts, by now largely successful, to take control of the Gallery Society which is/was unique amongst major Australian galleries in having a large measure of independence and its own constitution; of voluntary guides, all members of the Society, being forbidden to work at front desks meeting and welcoming visitors – this task devolving to a fully paid and uniformed corps of casuals. It tells of a new culture of secrecy, of silence, of non-disclosure agreements, and of fear; of staff having to sign a Code of Ethics and Conduct whereby employees can be summarily dismissed if engaging in misconduct, so defined to include criticism of the Gallery – a proven and effective method of silencing whistleblowers. The book also hints at, sometimes tells of, the frustrations of new management in feeling thwarted in their attempts to progress an agenda they genuinely feel necessary – “Why is everything so complicated here?” asks one, “it’s just a building with paintings on the wall.”

Overarching, perhaps driving, it all is Dr Brand’s ambitious plan to build an ‘extension’ to AGNSW. The new will link with the old, out across a corner of the Domain, a grand new entrance extending across the green space and land bridge above the Cahill Expressway, to cascade in a series of tiers down to the water near Woolloomooloo where grass now covers the old oil storage tanks. The whole, to be called Sydney Modern, notwithstanding Sydney’s excellent Museum of Contemporary Art around the corner at Circular Quay, will come at an estimated cost of $460 million. Its opening is still said to be in 2021, but as at May 2017 funding remains uncertain. Sydney Modern has divided the Arts community. More importantly, it has raised the important issue of Art versus Money in the context of a new gallery predicted to achieve significant revenue from corporate sector use of its space as an events and promotional stage.

All this when one view has it that an international tide is turning against the building of mega centralised infrastructure for the Arts, and when closer to home, the Barangaroo complex with its massive conference and entertainment facilities is now coming on stream virtually next door to AGNSW. Nowhere is the looming confrontation more starkly evident than in this snapshot of financial opposites: on one hand, an almost half billion dollar price tag for Sydney Modern; on the other, the recent introduction of fees for school tours (or curtailment if remaining free) – even though the tours are conducted at no cost to the gallery by volunteer guides.

While Culture Heist is about the fracas within AGNSW and the dilemma it faces, the book is much more than merely an account of a parochial power struggle within one art museum – even if this is a central theme – and raises fundamental issues of entitlement and privilege in society. Professor The Hon Dame Marie Bashir AD CVO, Governor of NSW from 2001-14 says, “Judith White has written with firsthand experience and passion about the centrality of every society’s need for a vibrant artistic culture.”

Each chapter of Culture Heist has a fore quote. The first, “All that glisters is not gold”, appropriately comes from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice in that the book is about merchants and the mercantile; its setting on the shores of Sydney Harbour rivals that of Venice, and the future it forebodes would seek to rival the festival and carnival of Venice. Former Prime Minister Paul Keating has denounced Sydney Modern as “a large entertainment and special events complex masquerading as an art gallery.”2

Click HERE to see property super agent Monika Tu celebrate in grand style, hosting her 2016 annual Black Diamondz Chinese New Year event at the Art Gallery of NSW.

The book is particularly well written with the author marshalling the complex facts and statistics supporting her thesis in a clear, logical and succinct presentation. Although her colours are well and truly nailed to the mast, given that her personal experience at the gallery over the past five years must have bitten deep on many occasions, Culture Heist presents as a remarkably objective and relatively impartial account. That said, the writer’s use of adjectives betrays her hand on more than one occasion – parting curators who had been dismissed, made redundant or otherwise removed can be ‘legendary’, whereas new-speaking and new-brooming marketing and communications managers are more testily referenced: “I had no idea how I would relate to someone whose use of the English language involved describing herself as a ‘creategist’, ” writes the author and then quotes this person’s exasperated query as to why everything is so complicated in a building with just paintings on the wall. But if former curators with extensive experience and deeply ingrained understanding of the collection and who also have track records of exhibitions and catalogues lauded as exceptional by peers and public alike, why not call them for the legends they are? And, in acknowledging the Zeitgeist, why not quote a creatgeist?

On one view it is tempting to see history as an endless chronicle of dispossession. As tragic as is dispossession by way of conflict, as inevitable as it is with the rise and fall of empires and nation states, far more insidious is dispossession from within by way of redistributions of the common weal – the ‘wealth’ that a people hold in common. Indeed this more subtle dispossession has never abated, and it is small comfort to realise that in the long sweep of time the dispossessor in turn becomes the dispossessed. Whether the redistribution was of rural land centuries ago by means of legislative fiat in Enclosure Acts, or by setting fire to roof timbers in Highland Clearances; or more recently of city land by slum and industrial clearance and redevelopment; or whether it is a far more recent struggle at the heart of many cultural institutions: the conflict between the public good and the forces of corporatisation; whatever its cause, the flow is invariably in one direction – from the relatively many to the relatively few. In the cultural sphere, as its blurb states, this book is timely in breaking the silence about an often covert struggle.

By way of example, culture in Western Sydney is significantly underfunded compared with Eastern Sydney. In 2012/13, Western Sydney’s population of more than 2 million (almost 10% of the national population) was catered for by local and state government funding of its five major cultural venues to the tune of $15 per attendee, whereas the figure for Eastern Sydney’s six main venues was more than $60 per attendee. Adding the huge cost of Sydney Modern to this imbalance will further widen the gap of privilege, bringing the cold winds of possibility to Margaret Thatcher’s economic-rationalist mantra that “there is no such thing as society.”

Warnings on privilege and entitlement in the world of culture are not new. “We know that certain minds can create an order in the chaos of appearances which other minds can contemplate with delight. We know that certain eyes can see in nature shapes and colours to which our eyes were blind”. So wrote Sir Kenneth Clark in his 1945 essay Art and Democracy just before he vacated his directorship of Britain’s National Gallery. On the question of the mass marketing of art he continued: “market research, listener research, and all the other means of measuring mass desires … these are instructions in the destruction of civilization as potent as the flying bomb and the tank.”3 Four years later, perhaps in search of such minds and eyes, he visited Australia – where he would find them in the foyer at AGNSW. They belonged to Sidney Nolan.

Brian Adams, Nolan’s first biographer,4 recalled Clark’s visit to AGNSW when recently writing a Centenary tribute to Nolan. “I paid a visit to the Art Gallery of New South Wales during February this year. I wanted to see what had changed since I was last there a couple of years before, and walking into the main entrance gallery, I found it looking brighter and more impressive than I remembered from many days filming there in the past with Christo, Gilbert and George, Robert Hughes and Sidney himself. I asked about plans for Nolan’s centenary at the information desk. Staffed by three smartly dressed staff wearing the sort of uniforms seen behind the reception desks of upmarket hotels, I asked a young woman what special events were being planned by the gallery for Sidney Nolan. She lost her smile of greeting, looked blank for a moment and then asked, ‘Would you spell that name please.’ …. I waited bemused, recalling this was exactly the spot where the artist in question, was ‘discovered’ by none other than Sir Kenneth Clark from London.”5

Some words from Yoshio Taniguchi, architect of MoMA, are an apt fore quote to the chapter titled Brand Designs: “Architecture is basically a container of something. I hope you enjoy not so much the teacup, but the tea.” Teacups indeed! Whatever one’s persuasion, all involved in the unseemly imbroglio descended upon AGNSW over the last five years must surely think they’ve been at a mad hatter’s tea party – one with malice in (what could have been) wonder land.

Judith White concludes her call to put a stop to the culture heist with this cautionary observation: “Public museums and galleries are not the property of those entrusted with their care. They do not belong to the directors and executives who manage them, nor to the boards who oversee them, nor to the governments responsible for their care. They belong to the people – and not only to the existing audiences, but to the multitude who have yet to claim their right to experience the transformative power of art and culture. And they belong to generations yet to come.”

Feeding as it does into the so-called culture wars, this book should make all gallery-goers very angry – whichever side of the argument they take. If you feel that the rot has set in you should be very angry. If you think it’s not rot and you support the Sydney Modern concept, but learn that the project has seemingly stalled, you should be very angry. The book will even anger those who have never entered an art gallery and simply wonder what all the fuss is about, but in reading it discover something new: in the words of Dr Richard Beresford, one of the many recent but now former AGNSW curators, that “art was there not so much to educate as to inspire. And anyone has the capacity to be inspired.”

Culture Heist is a call to arms, a catalyst to speed up a reaction. It should be read by all.

OTHER REVIEWS

Art Gallery of NSW in critical sights of Judith White’s Culture Heist, Patricia Anderson, Weekend Australian – Review, p. 25, May 13, 2017

ENDNOTES

- In 1836 John Graham ‘rescued’ the shipwrecked Eliza Fraser from her aboriginal hosts at Lake Cootharaba and delivered her to soldiers waiting on the beach north of present day Noosa. Fraser Island is named after her, as is Sidney Nolan’s painting Fraser Island in the AGNSW collection.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 2015.

- Kenneth Clark, “Art and Democracy” in Cornhill Magazine 161, July 1945, p. 370.

- Brian Adams, Sidney Nolan: Such is Life, Century Hutchinson, Melbourne, 1987.

- He saw Nolan’s painting Abandoned Mine which had been entered in the annual Wynne Competition for landscape. Brian Adams’ tribute to Nolan, Expatriatism in excited reverie, is available here: http://nolancentenary.com.au/expatriatism-in-excited-reverie/.