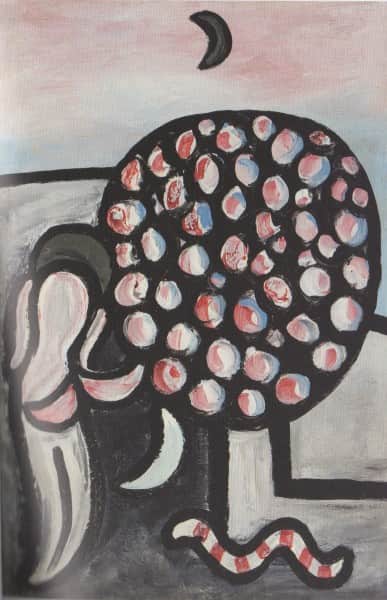

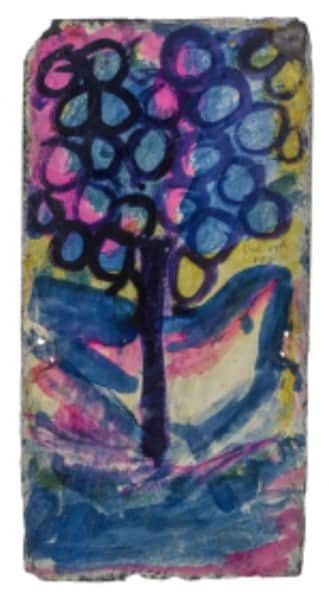

Sidney Nolan, “Woman and Tree” aka “Garden of Eden”, 1941, Heide collection

This evocative little image in gentle blues, whites and pinks set against the bold black outlining, is the first painting by Nolan reproduced in print.

Inscribed Garden of Eden, it appeared as Woman and Tree in the 2nd edition of Angry Penguins which went to print in August 1941 when still produced in Adelaide with Max Harris the sole editor. A few weeks later, again titled Woman and Tree, it was included in the 3rd annual exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society which opened on 9 September 1941 at David Jones Gallery in Sydney. The exhibition was also scheduled to hang in Melbourne and Adelaide, but only the Melbourne show proceeded, opening at the Hotel Australia on 14 October. Listed as no. 167 in both Melbourne and Sydney catalogues, Woman and Tree was marked N.F.S. – an indication of its importance to Nolan. It also appeared as the cover illustration on the programme for CAS’s First Concert of Contemporary Music held on 21 October, and a little later was included in the December 1941 edition of Art in Australia. All illustrations were in black and white.

It was not then exhibited for over 40 years, while in the possession of Sunday and John Reed, from whose bequest it became part of the Heide Park and Art Gallery collection in 1982. Shown that year in Heide’s Glimpses of the Forties exhibition, it has since been included in major Nolan exhibitions including Jane Clarke’s masterly Landscapes and Legends retrospective at NGV to mark Nolan’s 70th birthday in 1987. Its long disappearance and subsequent emergence soon after the Reeds’ deaths as part of their own collection, has tended to fix the work in the minds of most as being emblematic of the relationship between Sunday Reed and Nolan – notwithstanding Jane Clark’s indication that the poetry of Rilke was the prime source of Nolan’s imagery.1

The Rilke poem quoted by Clark is Annunciation (Words of the Angel) which begins:

You are not nearer to God than we,

and we are far at best,

yet through your hands most wonderfully

his glory’s manifest.

From woman’s sleeves none ever grew

so ripe, so shimmeringly;

I am the day, I am the dew,

you, Lady, are the Tree.

Years later, Michael Keon, an habitué of Heide in the early years of Nolan’s presence, wrote of the Rilke influence in this painting, saying “And, if Nolan insisted that his inspiration had come from Rilke’s lines, ‘I am the day I am the dew, / you, Lady, are the Tree’, and also had put a striped and wiggling snake at the foot of the Tree, well, let him have his head, he was off and running.” Keon clearly believes that the work is about Nolan and Sunday. He says “Painted at Heide. Sunday was woman, tree an almond in flower outside Heide’s backdoor. I watched Sunday and tree come together”.2 His assessment may well have been influenced by the fact that Nolan had most probably removed him from Sunday’s affections.3

Woman and Tree is one of several rather similar works by Nolan done during a 12 month period from around mid 1941. Here are some of them:

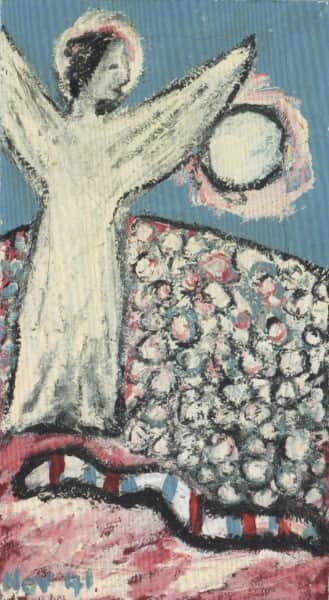

Sidney Nolan, “Angel and Tree”, 1941

Sidney Nolan, “Garden of Eden”, Nov 1941

Sidney Nolan, “Lovers, Tree and Moon”, Dec 1941

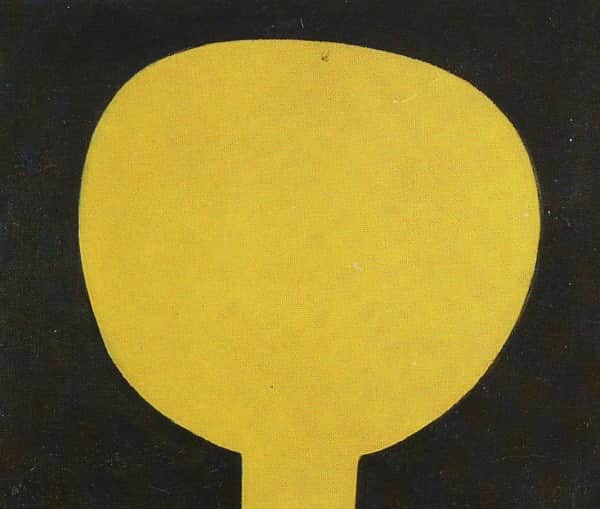

Sidney Nolan, untitled (Round tree), c. 1941, AGNSW collection

Sidney Nolan, untitled (Round tree), c. 1941, AGNSW collection

Sidney Nolan, “Figure and Tree”, 1941, b & w reproduction in “Such is Life”

Some common elements are discernible in these paintings. Most reference Nolan’s ground-breaking work Moonboy which was painted in 1939 or 1940. All have a tree or part thereof. Most have a moon. A couple have a Garden of Eden snake beside the tree. All have either winged angels or figures without wings, either single or coupled. The coupled chrysalis-like wingless figures in Lovers, Tree and Moon are very similar to those below in Lovers, Luna Park from 1941.

Sidney Nolan, “Lovers, Luna Park”, 1941

A number of sources inform these works. The reference to Moonboy as seen in the trees is readily apparent, and the temptation in the Garden of Eden, its tree and the snake are also rather obvious, given that Nolan’s first marriage was collapsing under the strain of his association with John and Sunday Reed at Heide.

“Moonboy” or “Boy and the Moon”, c 1939-40, Sidney Nolan, NGA collection

Many of the works have a distinct Rouault-like heavy outlining – perhaps hardly coincidental given that the June 1941 edition of Art in Australia included an article on Rouault together with images!

Georges Rouault, “Odalisque”, reproduced in ‘Art in Australia’, Jun 1941, p. 29

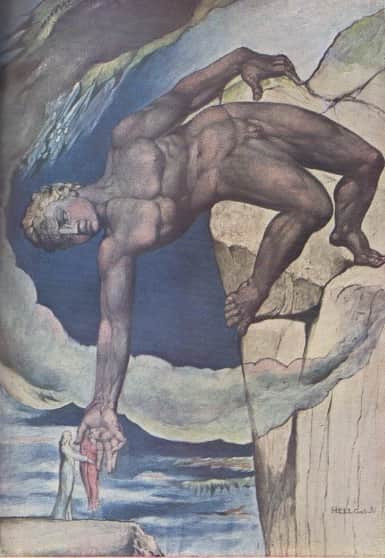

The sources for these Nolan works, particularly their figurative elements, go beyond Rilke and beyond the more obvious allusions mentioned above. Jane Clark refers to the influence of William Blake and a set of Blake watercolours acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria in the late 1930s which were included in an article by Daryl Lindsay in the March 1941 issue of Art in Australia.4 The following images from that issue certainly might have been one catalyst:

William Blake, images of angels reproduced in ‘Art in Australia’, Mar 1941, p. 38

William Blake, Asteaus sitting down Dante and Virgil, reproduced in ‘Art in Australia’, Mar 1941, p. 39

Winged angels also appear in a set of photographs in the December 1941 edition of Art in Australia illustrating magnificent 14th century bas-relief carvings in Orvieto cathedral. Seen below, these too may have influenced Nolan’s imagery even though some of his works were most likely done earlier than this publication.

14th century bas-relief angels in Orvieto cathedral, “Art in Australia”, December 1941, p. 47

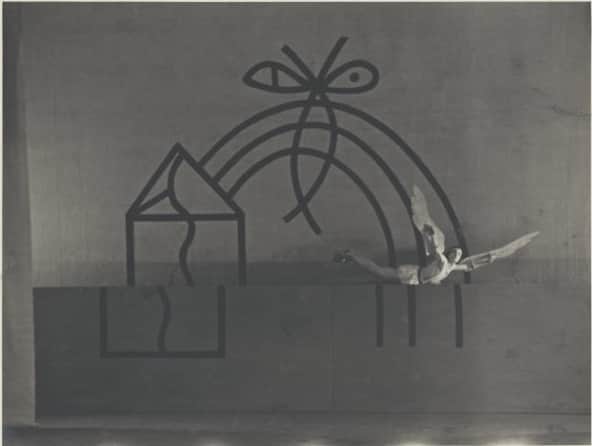

However the most potent winged image informing these works is perhaps to be seen in the photo below from the Ballets Russes production of the ballet Icare for which Serge Lifar commissioned Nolan to design the sets. Whilst his first design was based heavily on his Blakean tent imagery and rejected, his second design was structured so that the winged Icare could be seen to fly and was a resounding success. Nolan and Elizabeth, the Reeds and Alannah Coleman were at the Sydney opening in February 1940 at what was his first public affirmation.

Sidney Nolan, set for “Icare’. Roman Jasinsky as Icare, the Original Ballet Russe, Australian tour, His Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, May 1940 / Hugh P. Hall

Woman and Tree is best known of all these works and as already mentioned, has usually been associated with the relationship between Nolan and Sunday Reed. It is easy to see why this connection has been made over time. The work was painted around the time of the collapse of Nolan’s first marriage and his moving in permanently at Heide, it was in the Reed’s possession and was not one of the 280 paintings returned to Nolan in the 1958.

The work would seem to have been of great importance to Nolan given that it was marked NFS, not for sale, when exhibited in 1941. Moreover he retained in his own possession all the other similar works illustrated above. It seems most unlikely Nolan would have kept them for all those years if they were closely linked in his mind to Sunday, given his increasing antipathy towards her. She, on the other hand, may well have thought from the very beginning or quite soon after that Woman and Tree was a testimony to their love. She certainly seems to have thought this of the little Lovers, Luna Park work above, which always hung on the wall of her dressing room.

During the 12 month period Nolan painted these works, he also made a number of quite extraordinarily simple evocative little images in enamel, oil, inks and gouache on discarded roof slates. Of them Jane Clark says: “Swiftly executed, utterly – almost naively – simple, several of them echo the imagery of Rilke’s poem Childhood, which concludes:

And hours on end on the grey pond-side kneeling

with little sailing-boat and elbows bare;

forgetting it, because one like it’s stealing

below the ripples, but with sails more fair;

and, having still to spare, to share some feeling

with the small sinking face caught sight of there:-

Childhood! Winged likenesses half-guessed at, wheeling,

oh where, oh, where?

“Sometimes Nolan’s angels swing through the air like acrobats, often there are flowers, lovers’ faces and ‘gentle hands this universal falling can’t fall through’. Nolan recalls that Rilke’s Fifth Elegy had a special impact on his imagination at this time – with images of lovers, angels, hands picking flowers and tingling feet.”5

Several of these roof slates are shown below.

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, ‘Ship’, 13 Jan 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, untitled, c. 1942, Heide collection

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, untitled (Icarus), 22 Jan 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, “Boat”, 2 Feb 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, untitled (boat and angel), 13 Jan 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, ‘Ship’, 13 Jan 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

An exhibition of them is imminent. We who love: the Nolan slates – will open at the University of Queensland Art Museum on Thursday 21 April 2016. A poignant reminder of the special place of these slates in Nolan’s affections is to be found in a short video presentation of his studio at The Rodd. In it can be seen a gathering of toy sailing boats, still there almost 25 years after his death.

Toy boats in Nolan’s studio at The Rodd

However I suspect neither the slates nor the paintings were executed with Sunday Reed primarily in mind – rather it was his first wife Elizabeth and their little daughter Amelda whose presence (mainly absence) most influenced the creation of these works.

Several sources chronicle the breakdown of Nolan’s marriage to art student Elizabeth Paterson. Four books in particular combine to give a comprehensive overall picture, although it remains difficult to be precise with the timing and the fluctuating intensity and domicile of the two relationships Nolan was maintaining. These four books are Brian Adams’ 1987 biography Sidney Nolan: Such is Life which can be regarded as Nolan’s own account, Frances Lindsay’s 2007 essay Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier which can be seen as telling the story from the viewpoint of his first family, and two publications in 2015: Nancy Underhill’s biography Sidney Nolan: A Life, and Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan’s Reed biography Modern Love.6 The following account is given by way of brief summary.

Nolan and Elizabeth were married in December 1938 not long after he first met the Reeds and began visiting Heide. For most of 1939 the newly-weds lived away from Melbourne at Ocean Grove where the Reeds were frequent visitors, and even during this first year Nolan and Sunday were showing signs of physical as well as intellectual attraction. Returning to Melbourne in late 1939, Nolan and Elizabeth worked together in a pie shop to make ends meet, worked together artistically on the Icare ballet with Sid designing the set and Elizabeth the costumes and headdresses, and they attended the opening night in Sydney on 16 February 1940 along with the Reeds. In June when Elizabeth discovered she was pregnant, their relationship had become increasingly strained by Nolan’s absences at Heide.

The Reeds suggested that when the baby was born the family should move to Heide, a suggestion firmly quashed by Elizabeth. Nolan and Sunday most likely became lovers during the pregnancy, if not before, and rather than moving en familie to Heide after their daughter’s birth in January 1941, Elizabeth returned to her parents’ home. Nolan began living at Heide soon after but began attempting, unsuccessfully as it transpired, to repair the damaged fabric of his marriage. In the lead up to Easter in April 1941, he undertook a solo bicycle ride in Tasmania to think things through, only to return to a letter from Elizabeth telling him the marriage was definitely finished. Unbeknown to Nolan, while he was in Tasmania, John Reed had met with Elizabeth and told her that Nolan would never reach his full potential with her beside him – and most likely also told her the extent of his relationship with Sunday. Nolan made further attempts at reconciliation but when these proved fruitless, he moved in at Heide on a permanent basis most likely in June 1941.

These bare facts scarcely hint at what the intensity of Nolan’s conflicting emotions must have been during this period of juggling his ambition with his responsibilities, and attempting to balance irreconcilable loves for a wife, a lover and a daughter he had hardly seen. Neither do they allude to the many real advantages brought to his career by his association with the Reeds.

In her essay Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier, Frances Lindsay writes: “His love of St Kilda reflected nostalgia for his youth, but also sentiment for his first wife, Elizabeth Paterson and their daughter Amelda who shared many walks with him along the pier. One one occasion he pointed to the window of an upstairs room in Marli Place on the Upper Esplanade and said: “I don’t wish to be indelicate, but that’s where you started life.”7

Marli Place, 3-7 The Esplanade, St Kilda

His painting St Kilda Pier was made from this vantage point. The wrought iron work on the verandah and the sweep of the pier remain evident in a contemporary photograph.

Sidney Nolan, “St Kilda Pier”, c. 1940

St Kilda Pier as seen today from the verandah of Marli Place

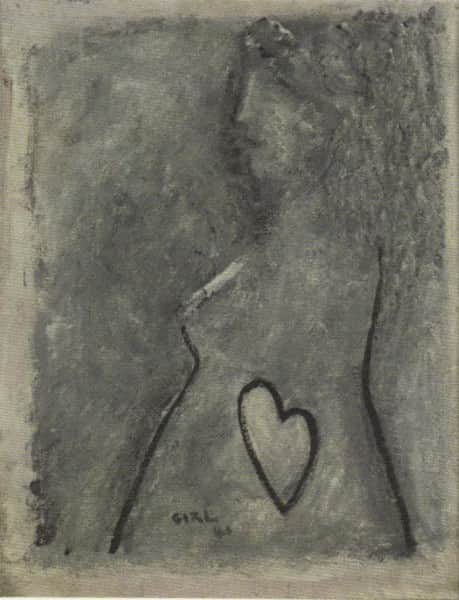

Early in 1941 Nolan also painted the delightful image Girl, depicting a heavily pregnant Elizabeth in profile with a heart drawn over the baby. Nancy Underhill has written “it is one of the most poignant declarations of love imaginable.”8 Their daughter Amelda was born on 18 January.

Sidney Nolan, “Girl”, 1941

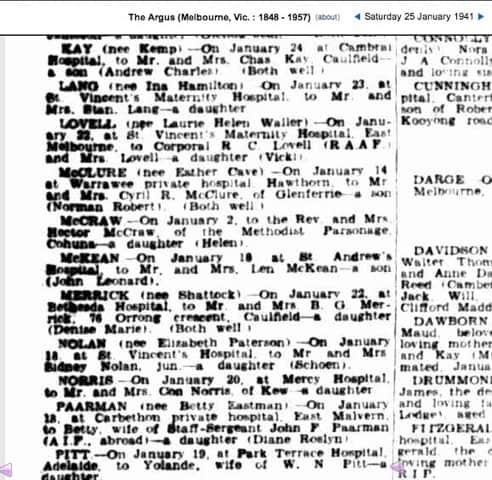

The birth notice appeared the following Saturday: “NOLAN (nee Elizabeth Paterson) – On January 18 at St Vincent’s Hospital, to Mr and Mrs Sidney Nolan, jun – a daughter (Schoen).”

The Argus, Melbourne, 25 January 1941, ” …. to Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Nolan, jun. – a daughter (Schoen).”

One can speculate as to why the name Schoen was chosen and why it was not used. Schoen is the anglicised version, without an umlaut, of the German word ‘schön’ meaning ‘beautiful’. Perhaps on reflection it was thought that such an obviously German word was not an ideal name for an Australian baby during World War II. However the intended name Schoen gives a special significance to this little 1941 painting on glass, A boat and a tree for Schoen, given the close likeness it has to Woman and Tree with its Annunciation theme.

Sidney Nolan, “A Boat and a Tree for Schoen”, c. 1941

A boat and a tree for Schoen also bears a strong likeness to the painting below, rendered on the verso of the slate inscribed Ship.

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, verso of ‘Ship’, untitled (Boat and tree) 17 Dec 1941, UQ Art Museum collection

The dense interweavings of imagery found in these works, associated as they are with conception, birth and childhood, stir the imagination but also point to the conflicting senses of loss and love Nolan must inevitably have experienced during this fraught period.

Another pointer to his wife and child being an inspiration for these images is to be found in the catalogue for a Sotheby’s 2001 auction at which Lovers, Tree and Moon was offered.9 Mary Nolan says of this work “This must refer to his first wife Elizabeth ….. this is an important painting.” The catalogue states that the work (and also Angel and Tree – both illustrated above) relate to his ‘”highly personal poetry from those same years” and quotes the lines I had a hill and night / with frost and on the moon / was mist / the valley held an angel / and in his hands were trees. This stanza is from the poem “Rime” published in the Judith Wright edited Australian Poetry 1948 with the author listed as S.N. The poem certainly invokes angel and tree imagery, but it was written much later, most likely in late 1946 or 1947.10

It is probably unwise to place undue emphasis on likeness when investigating sources for Nolan’s images, particularly facial features in works executed as rapidly as the slates would seem to have been. However two of the slates, each depicting a face-to-face couple, offer some clues as to who might be portrayed – less because of any great difference in profile, rather a discernible difference in the hair. Elizabeth’s hairstyle at the time is described as being “a dark Egyptian bob,”11 whereas Sunday had “fairish hair tied hard-and-fast back on nape of neck.”12

Of the slates illustrated below, the first, with its bunch of flowers, would seem more likely to portray a dark bob, the second more likely fairish hair tied back.

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, untitled, c. 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, untitled, 29 Jan 1942, UQ Art Museum collection

An interesting common feature is that the two facing profiles, set against their black tile ground, each create the effect of a vase or candle stick not dissimilar to the vase in this Still Life painted soon after. Nolan had no shortage of visual prompts stored away in his eidetic memory!

Sidney Nolan, “Still Life”, c. 1945

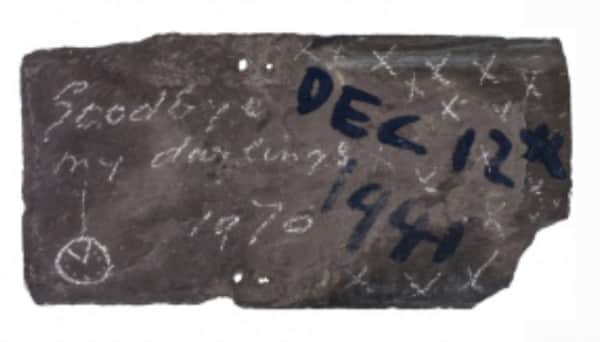

The following slate however, and the verso inscription made almost thirty years later, is revealing. The painting is dated 12 December 1941, by which time Nolan had been finally parted from Elizabeth and his daughter for six months, and was contentedly enmeshed in the ménage a trois at Heide.

Sidney Nolan, painting on slate, untitled, 12 Dec 1941, UQ Art Museum collection

None the less, the woman portrayed certainly does not have fairish hair tied back hard and fast. On the contrary, whether in an Egyptian bob or not, the hair is dark and the style certainly resembles that of Elizabeth seen in this photo of her at art school.

Elizabeth Paterson at art school

On the verso of this slate Nolan has chalked many kisses, written “Goodbye my darlings 1970”, and drawn a fob watch ominously recording the eleventh hour – all convincing and potent indicators of his feelings for the works.

Sidney Nolan, inscription on verso of painting on slate, untitled, 12 Dec 1941, UQ Art Museum collection

The statement as posted immediately above requires correction. Two weeks on since it was written, I have now read the excellent essays by Nancy Underhill and Chris McAuliffe in the catalogue for the exhibition We who love: the Nolan slates at the University of Queensland Art Museum. My assertion above that Nolan chalked the “Goodbye my darlings” message on the slate verso is incorrect. Nancy Underhill states that the slates were not returned to Nolan by the Reeds in 1958/9 along with the shipment of some hundreds of other works (as I had assumed, thinking further that Nolan sent them to Jack Lynn at the Powerhouse in 1970.) Rather, Underhill advises that Albert Tucker’s wife Barbara told her that she was at the Windsor Hotel in Melbourne, where Nolan was staying in 1970, when Sunday Reed left them there for him to collect.13 Moreover, Kendrah Morgan advises that the chalked printing is undoubtedly in Sunday’s hand.14

It should also be mentioned that in his catalogue essay Chris McAuliffe argues strongly, as did Michael Keon whom he frequently quotes, that Nolan’s inspiration for the slates came from Sunday Reed, and that the slate paintings are intrinsically linked to his feelings for Sunday during that first year before his call up for army service. McAuliffe traces the slate imagery through Blakean, Rilkean and many other literary influences, through the influence of other painters, and as informed by day to day Heide happenings such as lovers’ tiffs, fits of pique and ceremonial gifts. His account is finely detailed and in my view, essential reading for those seeking a deeper insight into what made the relationship tick, and – like the eleventh hour clock on the goodbye message – stop ticking.15

Nevertheless, in my view it is still reasonable to alternately conclude that, just as Nolan did not paint his Mrs Fraser work in 1947 with malevolent intent directed towards Sunday Reed foremost in his mind (see Nolan’s “Mrs Fraser”: Reconstruction and Deconstruction on this website), neither did he paint Woman and Tree, his first reproduced work, or any of the closely associated works outlined above, primarily with her in mind. That said, it is certain that during the twelve month period in which these works were painted, the intellectual, sexual and financial splendours of life at Heide quickly overwhelmed his feelings for the more likely inspiration for these intensely personal, beautiful works – his first wife Elizabeth and their daughter Amelda.

Not the first male in his early twenties to be overwhelmed by the allure of the older woman (he was 24, she 36), Sunday came with much more than mere trophy status. Whilst the imagery in these works may not have been inspired by her, the depth of his feeling for her, as evident in his love letters from the Wimmera during 1942-3, should not be underestimated. Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan write that “towards the end of 1941 Sunday’s relationship with Nolan had developed into more than a passionate physical attachment, and there was no doubt in the minds of those close to them that the pair had fallen deeply in love ….”16 – a love however, destined not to last. It is not difficult to imagine how his later feelings regarding the events of this brief but critical period fed into the mental cauldron that thirty years later would spew forth the Paradise Garden poems and drawings.17

Neither should Nolan’s driving ambition be underestimated, nor forgotten, when looking back over these paintings and at what they say. Missing from them all is any hint of a Faustian bargain. In the words of Nancy Underhill: “Nolan allowed his ruthless artistic ambition and his enchantment with being considered wondrous to lay waste to his marriage.”18 Indeed it seems ironic that ‘schoen’ – in German ‘schön’, the name he chose for his daughter’s birth notice, is to be found in the phrase used by Goethe to define the bargain Faust struck with Mephistopholes. If ever, for even an instant, Faust says to the devil, I mutter the words “Verweile doch, du bist so schön” – in English “Stay a while, you are so beautiful”- then my soul is yours. One wonders whether Nolan ever came to think of this period of his life in such terms.

At the time, he perhaps knew these words from Faust – he was after all reading Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer – but if not, they would have soon come to notice. In early 1943 Angry Penguins no. 4 was published and included Max Harris’ poem “The Word” with the sub-title dedication “For Mary Boyd”. Closely involved in the Angry Penguins productions, Nolan would have known that “Verweile doch, du bist so schön” was written on Harris’ type-written manuscript beneath the dedication. The phrase does not appear in the poem as published, and editorial discussions can be imagined to decide whether in 1943 these German words would have reflected poorly on the journal.19

Whether or not these years can be thought of in Faustian terms, it is tempting to regard them, and their aftermath, in the Keatsean imagery of La Belle Dame sans Merci. Keats’ well known poem of seductive enthralment can be seen as evocative of Nolan’s life from his early twenties. He had ‘met a lady in the meads, full beautiful – a faery’s child, Her hair was long, her foot was light, And her eyes were wild.’ Much of the poem is redolent of Heide – consider the line ‘she took me to her elfin grot.’ Later in life, whilst not exactly ‘alone and palely loitering,’ at times he very likely was ‘on the cold hill’s side … though the sedge is wither’d from the lake, and no birds sing.’ One can but wonder whether on occasions an inner voice did not whisper ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci hath thee in thrall!’

Woman and Tree and these other delightful works, intimate and revealing, can be seen as Nolan’s annunciation – in the literal sense of that word. They constitute a visual announcement, in paintings ripe and shimmering, of what had been his day, his dew, and what perhaps years later in quiet reflective 3am moments could still seem his tree.

END NOTES

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan: Landscape and Legends, A Retrospective Exhibition 1937-1987, University of Cambridge, p. 36. Jane Clark says this information came from Nolan with whom she went through most of the works in the exhibition a couple of times (email to the author, 23 March 2016).

- Michael Keon, Glad Morning Again, ETT Imprint, Sydney, 1996, p.139.

- Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Modern Love, Meigunyah Press, Melbourne, 2015, p. 107.

- Jane Clark, Sidney Nolan: Landscape and Legends, op. cit., p. 40.

- ibid., p. 40.

- Brian Adams, Sidney Nolan: Such is Life, Hutchinson, Melbourne, 1987, p. 54; Frances Lindsay, Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier in the catalogue Sidney Nolan, AGNSW, 2007, p. 67; Nancy Underhill, Sidney Nolan: a life, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015, p. 92; Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Modern Love, op. cit., p. 102.

- Frances Lindsay, Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier, op. cit., p. 67.

- Nancy Underhill, Sidney Nolan: a life, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015, p. 94.

- Sotheby’s, The Estate of Sir Sidney Nolan, Melbourne, September 16, 2001, p. 48.

- Ed. Judith Wright, Australian Poetry 1948, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, p. 76. Just days before he died, Barrett Reid, with whom Nolan stayed in Queensland after leaving Heide in 1947, was given a prepublication mockup of an anthology of his poetry, Making Country. (Barrett Reid, Making Country, Angus & Robertson, 1995.) On it he wrote personal comments and notes. A photocopy of the mock-up is in possession of the author. Against the poem “Regarding You” Reid has written “Nolan wrote a matching poem to this. Both published in Judith Wright’s Aust Poetry 1948”.

- Frances Lindsay, Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier, op. cit., p. 72.

- Michael Keon, Glad Morning Again, op. cit., p.82.

- Nancy Underhill, “Thoughts on Nolan”, in We who love: the Nolan slates, UQ Art Museum, Brisbane, 2016, p.92.

- Kendrah Morgan, conversation with author, April 2016.

- Chris McAuliffe, “Like phantoms in fate-laden dimness”, in We who love: the Nolan slates, UQ Art Museum, Brisbane, 2016, p. 9.

- Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, Modern Love, op. cit., p.112.

- Sidney Nolan, Paradise Garden, McAlpine, London, 1971. The book is a lavishly produced collection of the bitter poems Nolan wrote drawing on his Heide days and their aftermath, and is illustrated by him with crayon sketches on transparent overlays above the poems to sit opposite reproductions of flower paintings from his Paradise Garden work. Nolan has written that the Paradise Garden poems were castigating and quite savage. He wrote to his daughter Amelda, “You remember walking by that little bridge below the Esplanade (Catani Arch at St Kilda; author’s note) and we talked about writing some poetry. Well I have done some and published them with illustrations of Paradise Garden. But the poems are the opposite of the paintings. They refer to the rather night-mare period of my life at Heidelberg and are quite savage in a way that never happens in a painting. I hope to one day write a book in which the poetry celebrates rather than castigates, and is more like what I thought about at eighteen standing by that bridge.” (Sidney Nolan to Amelda Langslow, undated letter, c. 1971; reported by Frances Lindsay in her essay Sidney Nolan: the end of St Kilda Pier.).

- Nancy Underhill, Sidney Nolan: a life, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2015, p. 94.

- Mary Boyd became Nolan’s third wife in 1976, and it is coincidental that as I write this, news has come of her death on 6 April 2016. Vale Mary, who was indeed so schön .