In 2016, friend and fellow Nolan enthusiast Andrew Turley wrote and published A guide to the ladies: 59 works by Sidney Nolan – April 1964 to June 1964 which documents his research into the so-called “Adelaide Ladies”, a little known area of Nolan’s oeuvre. Andrew’s comments about these paintings on the recent ABC film documentary Nolan has sparked an interest in them and a call for more information, which this website is pleased to provide.

This posting on aCOMMENT of Andrew’s writing, made on his suggestion and with his encouragement and assistance, contains the Foreword, Introduction and Epilogue to his book.

“For Sidney Nolan, creating art was about more than dabbing paint on canvas. It was about digging deep into the red dirt of Australia, and into the soul of those who have lived and died here”.31/10/2007, Scott Bevan on the ABC

“The (Australian) faces and landscapes are clearer for me now than ever before, and I look forward to battling with them in paint”

22/3/64, Sidney Nolan on the ABC

Foreword THE BIGGER PICTURE

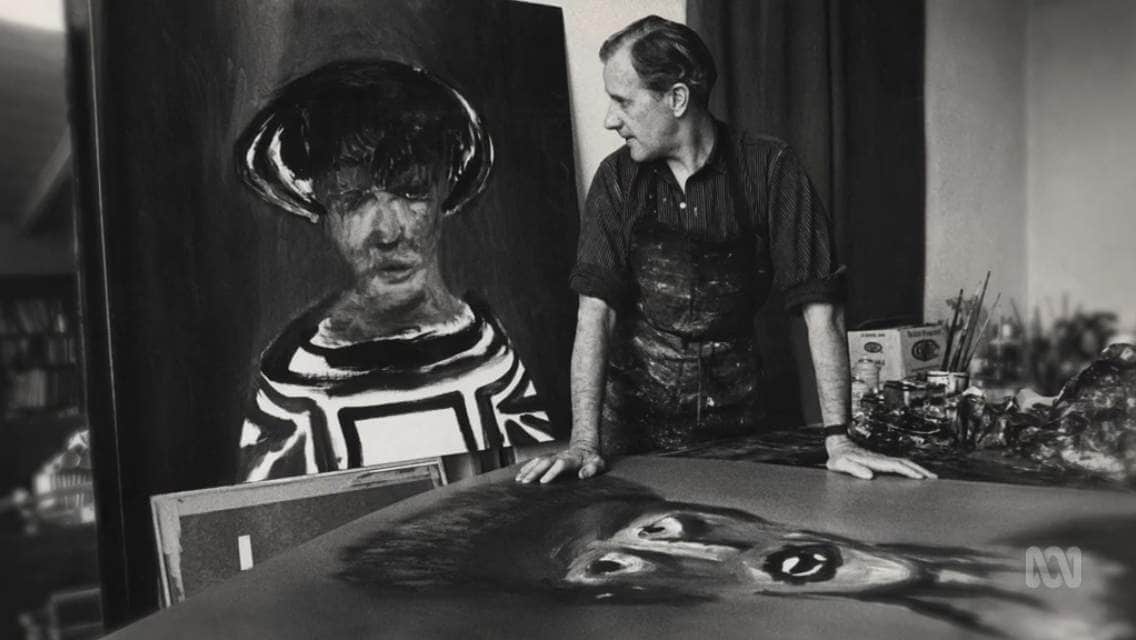

Sidney Nolan in his Putney studio 1964

This document is part way between research and a catalogue. Consider it a cast of characters reviewed in paint – which is, at least in part, true for a series with roots in Patrick White’s ‘Riders in the Chariot’. Sidney and Patrick both use their ‘ladies’ to draw out and reflect on a continuing theme, the conflict between outsiders and society. It is easy to imagine Patrick White’s well-informed postmistress, Mrs Sugden, and the socially questionable Mrs Colquhon from ‘Riders in the Chariot’ discussing the series:

“Who were those women? They appear unusual sorts of paintings” Mrs Colquhon would say, voicing her opinion with the hope that some kind of reassurance might spill from the stiff mouths and painted lips themselves. Mrs Sugden, knowing that if a Sidney Nolan painting is not a Ned Kelly it is judged somehow less of a painting, would reply dryly, “I cannot deny that they are different”.

They aren’t different for Sidney. Ned in a landscape might be Australia’s first love, but portraiture was one of his – from the abstract heads of the late1930s, the1947 series of friends and fellow artists now hanging at the Art Gallery of South Australia, his Gallipoli works that attempt to define the Australian national character through to a wide range of portraits, and of course many self portraits the last of which was painted in1988. But because they do not easily fit into the community of nationalised or popular forms they are less acceptable – much like some of the ‘Riders in the Chariot’ characters.

In 1964, just one month before launching himself into these portraits, Sidney declared himself at the top of his game. He said “The (Australian) faces and landscape are clearer for me now than ever before, and I look forward to battling them in paint”.1

This is a rare opportunity to catalogue the results of that battle, with the complete series side by side. To see the exceptional, good and not so good, in both the Australian faces he captured and the way of working that required Sidney to output work, masonite sheet by masonite sheet day after day until both he and the idea were completely exhausted. This subject matter and style of working was not truly in fashion in a mid 1960s world of Abstraction and Pop Art, however with the ‘many’ on show we can see how Sidney worked tirelessly to find the ‘few’ that captured the truth he was seeking: that deep sense of isolation and melancholy.

Lastly, but most importantly, this is a record for posterity. Only the most popular, commercial, critically acclaimed or fashionable works warrant the time of institutions or commercial organisations and with such an enormous creative output it is inevitable that the complexity and hidden depths of these less revered works will be lost.

Although constructing a complete catalogue raisonné on Nolan would be more than daunting for any scholar, perhaps this small bite will assist when one day someone attempts to “eat the elephant”.

Sidney was one of the most prolific painters of the 20th century and it has affected how his art is viewed. However, with a body of work estimated at up to 30,000 images he does not even come close to Picasso (a contemporary exhibiting at the same time in London) who has at times been attributed with creating up to 13,500 paintings, 100,000 prints and engravings, and 34,000 illustrations.

For Sidney quantity was a by-product of speed. And his speed in turn was in part a by-product of a lifelong obsession with French modernist poet Arthur Rimbaud, and the way that Rimbaud himself created. In Sidney’s mind speed eliminated contrivance, leaving pure emotion and unadulterated visual impulse. But this method had its pitfalls. For a work to be successful, everything had to fall into place in a single moment.

He said, “It’s the nature of the way I work, which is instantaneous…I put everything on the fact that I’ll get it right, but sometimes I don’t…if you don’t get it right like that, then there is no second chance. And the misses?… I don’t overwork them much, just discard them and keep them. I’m just as fond of them as the others. You don’t kill a dog because it limps. It limps but I still love it”.2

Some of the paintings recorded here limp, others show remarkable strength, but it was Sidney’s compulsion to simply paint, and to keep painting until his vision was spent that allows us to understand the risk he took with each output: “I’ve got to start working – without any forms visible in front of me, with nothing really worked out. One gradually trusts oneself to find them, you know. It’s a gamble…It’s a private kind of thing, and the public production and statement is only designed to reach other peoples’ inner ideas. Of course this means you must be prepared to suffer defeat after defeat as they crop up…I am never in the position of feeling I can do anything at will”.3

Seeing the works end-to-end, we can see distinct groupings and often four or five paintings bearing the same date. This does not necessarily mean Sidney painted them in a single day. In 1964 he explained. “To complete a painting it takes three days as a rule. It seems to work in a kind of cycle. The first day I need to be convinced enough to go on to the second day! I nearly always have a kind of crisis on the second day. But on the third day, generally speaking, I know whether I am going to win or lose”.4

Look carefully and you will recognise the germ of one painting infecting the next, as painting follows painting. A pattern in a blouse, a colour from the same tin of opened paint or stripes and lines all work their way from one sheet of masonite to another.

In the first half of the 1960s Sidney was at the peak of his powers. He became financially stable, and although he was conscious of commercial needs he was now painting what and how he wanted to paint. Life instead of myth. Critics be damned.

In 1983 art critic Terence Maloon pointed out that the drawback of course was that “Nolan isn’t like the legendary King Midas, but then neither was Picasso. Both Picasso and Nolan have produced huge quantities of slight, hasty, facile paintings and drawings, which have their moments but tend to crowd out the masterpieces”.5

There are masterpieces within Sidney’s Ladies, but they have been elbowed into obscurity by fashion and critical whim. And it’s not the purpose of this document to try and point them out – an individual should choose those paintings for themself depending on how the works connect with their own inner ideas.

But this is a rare opportunity to align the story of creation with the dates of creation. Irrespective of fame or relative obscurity there is an opportunity to link the strokes of the brush with the mind of the painter and follow a series from the germ of the idea, to the image that infected his mind and on through the fevered output to the point that “…out of this (prolific output) comes something that one hopes is successful – to oneself. And finally there comes your exhibition, which I like to think of as the sum of those paintings that I feel haven’t defeated me”.6

Seeing the series in full helps to reveal the story, the history and the bigger picture of Sidney’s ‘Adelaide Ladies’. By documenting them all, we can contemplate the victories and the defeats, and look forward to the time Kenneth Clark anticipated “when time has weeded out his colossal output and the didactic snobbery of abstract art has declined, he will be of even greater renown”.

Introduction MEET THE LADIES

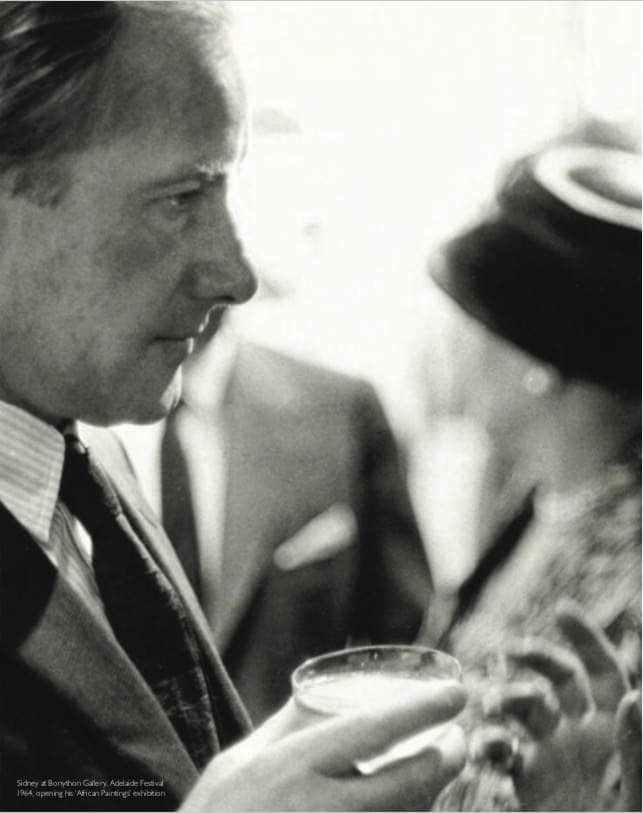

Sidney at Bonython Gallery, Adelaide Festival 1964, opening his ‘African Paintings’ exhibition

Their secrets and disguises

Sidney completed at least 59 works7 in the 46 days between 27th April and 11th June 1964. Inspired by Australian faces from Adelaide to Sydney they were not all taken from his South Australian experiences but explored the country’s contemporary character as a whole.

As 1960s Australia struggled to reconcile its emerging identity, and abstraction became the darling of the art world, Sidney created portraits of everyday women and gave them mythic makeovers, mixing national and international icons with memories of Adelaide’s light and the spirit of the country. His Ladies flashed around the globe on the covers of international bestsellers, took part in New York exhibitions and graced London poetry festivals, personifying Australian isolation and self-examination every time they appeared.

Just a decade before, the stereotype of an alien, inhospitable and unexplored outback full of mythic flora and fauna had fired the imagination of an austere post-war England. Hugely popular UK novels and stage plays set in Australia – “A Town like Alice” (1950) by Nevil Shute, “Voss” (1957) by Patrick White, the Nobel prize winner for literature described as ‘so clearly one of the great artists of our time’ and “Summer of the Seventeenth Doll” (1959) by Ray Lawler8 – were the beginning of an internationally recognised artistic tradition.

Nolan’s paintings of Ned Kelly and Burke and Wills had been exhibited to great acclaim in the UK at the same time, and they fed the stereotype. When Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh showed great enthusiasm and support for Nolan’s works, the fashion for Australian landscape and myth in the UK was firmly cemented. The nation was christened “Kelly”, “explorers” and “drought laden desert”.9

Yet by 1960 Nolan was exploring new ground. Storylines that had stayed with him for years, gestating, burst forth as fully formed paintings. Decades of Rimbaud seethed and twisted under Bacon inspired paint after his 1962 African experience. Hurley’s photographs of Antarctic explorers, remembered from his youth, shivered on the masonite after Nolan walked the icy wastes. And Patrick White’s sad and bitter society women from ‘Riders in the Chariot’ paraded to life in all their glory after the Adelaide Festival in 1964. It was in fact 1961 when White had insisted that the Nolans be the first Australians to read his ‘Riders in the Chariot’ manuscript, even before the publishers10, and for 3 years the images of primped hats and crimped smiles sat demurely in Sidney’s psyche.

Patrick White’s description of three particular “ladies of importance” would stay with him: “The first had an enormous satin bon-bon, of screeching pink, swathed so excessively on one side that the head conveyed an impression of disproportion…the second wearing on her head a lacquered crab-shell…one real claw offering a diamond starfish, the other dangling a miniature conch in polished crystal…the third wearing an innocent little conical felt, of a drab, an earth colour, so simple and unassuming that the owner might have been mistaken for some old, displaced clown, until it was noticed that fashion had tweaked the felt almost imperceptibly, and that smoke, yes smoke – was issuing out of the ingenious cone…as she sat in the centre of the smart restaurant her mouth crimped with pleasure”.11

Like a prophecy, White’s words would come true in Sidney’s Adelaide.

In 1964, at the Adelaide Festival, after driving from Sydney for the opening with Russell Drysdale and Hal Missingham (Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales), Sidney saw “the crowd of ladies young and old, all similarly wearing flower festooned hats as they paraded at the garden party”.12

In a letter to Cynthia Nolan he wrote of Adelaide “the light continues to pour down transfiguring what would otherwise be tawdry. Even the women in their great seaweed mop hats, coloured like lollies, have a totemic air”.13

“Tawdry” may have sat at the heart of his letter to Cynthia, but Sidney himself said that his series of Ladies was a commentary on country women who dressed up to come into town.14 Typical of his exploration of identity ‘tawdry’ was not a criticism. He knew, and had demonstrated time-and-time again, that both the heroic and the tragic formed part of the distinctive Australian consciousness. He also said of the trip, “I was fascinated by truly Australian faces. I found myself looking at them for the first time and I wanted to paint them, but not masked as I had painted Ned Kelly”.15

The women were anti-heroes, their countenance an attempt to hold a human significance in the vastness of the country, a modern representation of so much of the adversity, distance, size, social background and class difference in white Australia’s short but intense history. His desire to paint them was a way of capturing their spirit.

Where his visions of Ned Kelly, Burke and Wills or Mrs Fraser had always humanised Australian heroic figures the Adelaide Ladies epitomised the everyday, and soon after his birthday and ANZAC day1964, paintings erupted.

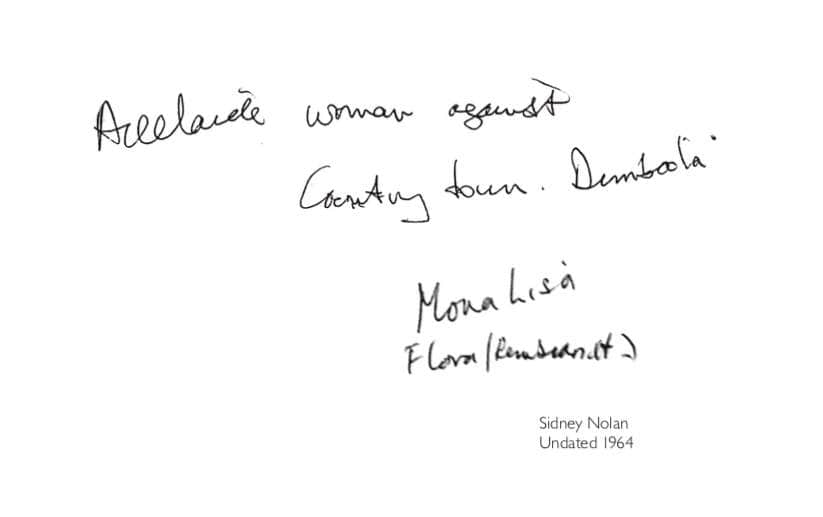

One of the many overlapping inspirations for the series was scrawled in his diary on Friday April 3rd1964 –his first entry on returning from the Adelaide Festival. It read: “Lunch Charles Osborne. Antarctic diary. London magazine drawings. Rembrandt etchings for Adelaide Ladies work”.16

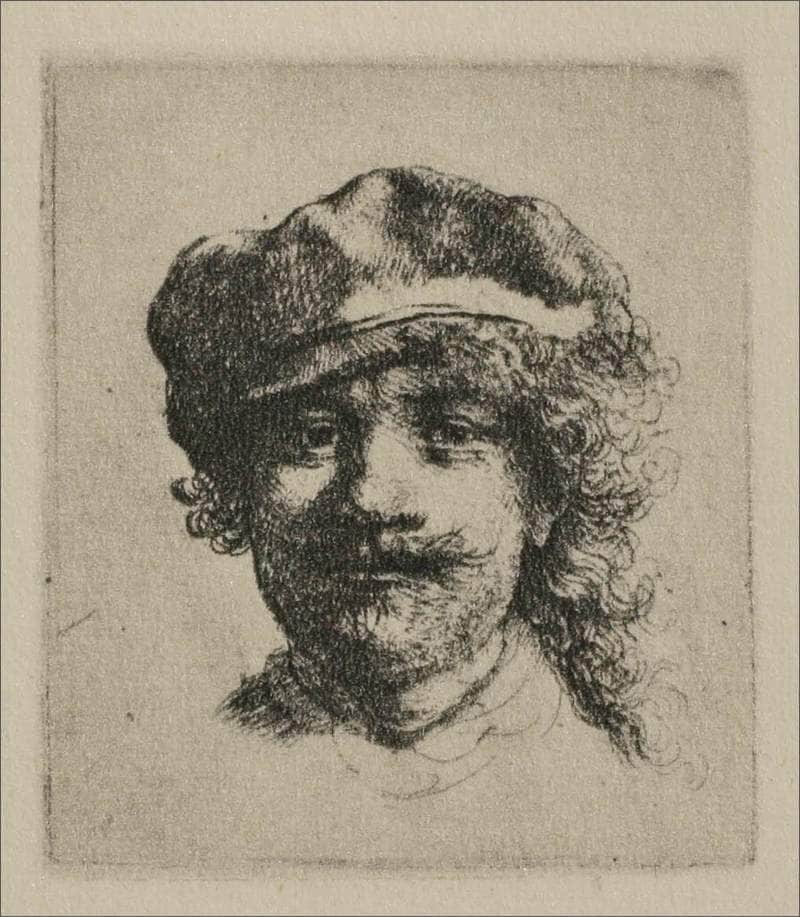

‘Self-portrait with Saskia’ (1636) etching by Rembrandt van Rijn. Purchased by the National Gallery of Victoria 1933

Sidney made specific reference to Rembrandt’s 17th century etchings, which he was likely to have first seen in the National Gallery of Victoria. The parallels of direct gaze and expansive hats are obvious. His enthusiasm for Rembrandt would probably have been sparked by Kenneth Clark, English art doyen, mentor and friend, who was writing ‘Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance’, published on1st January1966.The crux of it was “the creative process by which a great artist can adapt for his own use, the pictorial ideas of his predecessors” and how compositions were often taken from other sources to make use of the richness and depth of all visual culture.

The notion of ‘use and reuse’ recurs in the Adelaide Ladies. On April 26th1964 Sidney scrawled reminders in his diary that would soon translate into several of his more memorable individual images. “Paint 3 Adelaide ladies Ala (sic) Vermeer, Salome John the Baptist, Dobells Kensington lady”.17 The diary entries are key to unlocking the secrets of four prominent works – the “Englishness” of Dobell’s bitter urban soul in ‘Suburb’; the ironically untitled tribute to light and narrative drawn from Johannes Vermeer; the wholly Australian dried out ‘Country Woman’ masked in the landscape; and a portrait of Rembrandt thinly disguised as a “Sydney urban woman”.

In these four paintings Nolan continued to explore with irony, humour and genteel rebellion, a crisis of identity. Or as one critic wrote “…a variety of surface illusion… the passive blobs of matter which continually seek to establish an identity for themselves…”18

Sidney’s decades of portraits had always been uniquely ‘Nolan’. But they were often sustained by poetry, philosophy, politics and studies of every artist he could get his hands on, both ancient and modern. And in that April diary entry he was borrowing from the Dutch master Vermeer and renowned Australian Dobell for inspiration. He said “I have my own sort of ‘shorthand’ for remembering objects or scenes I want to paint later. Certain things hit me each day and I write them down in my diary, quite simple things…this might not mean anything to anyone else but it has the effect of taking me back to the moment…even in twenty years it will take me back…I just use this kind of memory aide”.19

‘Suburb’ dated (27 April 1964) by Sidney Nolan. Described in his diary as “green blue hat, lined face / Dobell’s Kensington lady”

Sidney didn’t need twenty years from the April entry. In fact he didn’t even need twenty days. His first distinctive group of Ladies was produced in the following three days and all had identities shaped by “the mother country”. Painted between the 27th and 29th of April in his Putney studio, the works ‘Head in profile’, ‘Suburb’, ‘Woman with spiked hat’, ‘Girl and the Moon’ and ‘Woman pink flower hat’ all projected a type of suburban class, temperament and British/Australian condition found in Australian society of the time.20

‘Suburb’ is the most English of them all. Arguably the strongest of the group it is a frontal assault on the senses. There is little doubt her ‘beauty’ was conceived on Nolan’s drive from Sydney to the Adelaide Festival with Russell Drysdale and Hal Missingham, AGNSW Director. The Dobell retrospective, due to open at the AGNSW five months later in July, was a hot topic of conversation. From pub to pub for 1,400km, they would have discussed Dobell’s work and particularly ‘Mrs South Kensington’, a work painted in London but held by the AGNSW since1943.21 Dobell had seen the woman who inspired the portrait sitting on a bench in Kensington Gardens and said he thought she typified the fashion of the time when women “all tried to look like Queen Mary”.22

‘Mrs South Kensington’ (1937) by William Dobell. Purchased by the AGNSW in 1943

Art critic James Gleeson described ‘Mrs South Kensington’ as “the extraordinary portrait of a dried-up spirit…narrow eyes, grey wrinkled skin, the bitter mouth and carefully fashionable hat”23 – all things Sidney observed of the Adelaide Festival audiences and remembered from reading ‘Riders in the Chariot’. In fact, a catalogue entry in the Tate records that Sidney confessed he was thinking of Australian country women and their “dried, sad look” when painting.24

If there was still any doubt about whether ‘Suburb’ was the ghost of ‘Mrs South Kensington’, on 27th April, the same date as painting ‘Suburb’, he wrote “green blue hat, lined face / Dobell’s Kensington lady”.25

Two weeks later on May12th a second distinctive group of ladies emerged. The light and perspective of Rembrandt and Vermeer took over from the scratch and blister of Dobell’s class commentary. Faces were now vague, awash with shadow, and features often difficult to define. But somehow, by leaving detail to the imagination, they became more, rather than less, expressive.

Kenneth Clark wrote “there is in nearly all of Nolan’s work this preference for the insubstantial and the unphlegmatic. His pictures levitate with surprising ease”.26 When Peter Fuller remarked on Clark’s reference and questioned Sidney about his “fluid and unsubstantial quality” in a1988 interview for the journal ‘Modern Painters’, Sidney responded with “Even when I was young I had this feeling of transience. This is the sense of melancholy”.27

His paintings on the12th certainly carried a moment of melancholy, and the day resulted in the most well known and well regarded works of the series: ‘Woman in Hat’28 was quickly snapped up by Lord McAlpine and now hangs in the Tate; ‘Head’ (green and orange hat) and ‘Woman’ (white hair) were seen at the 1967 AGNSW Nolan retrospective, reproduced in catalogues, magazines and newspaper articles; and ‘Woman’ (Young Prince of Tyre) eventually found her way back to the Art Gallery of South Australia after a name change marrying her to ‘Ern Malley’.

‘Lady Interrupted’ (12 May 1964) painted “Ala Vermeer” by Sidney Nolan

But most famous of all was ‘Lady Interrupted’. She was the “Ala Vermeer” – in the style of Vermeer – from Sidney’s diary on April 26th. Ironically she too was probably, although inadvertently, inspired by Kenneth Clark and Rembrandt connections more than a decade before. Sidney, as a naïve, newly emigrated antipodean, enjoyed both his first lunch at the Clark residence and an uncomfortable social encounter with a woman from the Louvre. Their clumsy dialogue revolved around whether Australia had any works by Vermeer in public galleries, to which Nolan replied there were none, but “there was certainly a Rembrandt at the National Gallery of Victoria”.29

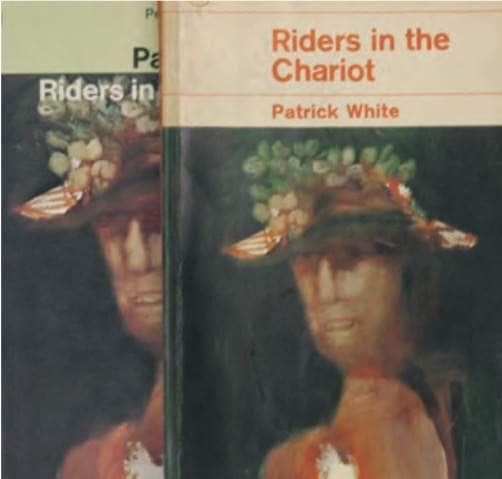

Whatever her origins, ‘Lady Interrupted’ became a symbol of the strong relationship Sidney was forming with the broader arts. She graced the cover of Nobel Prize winning author Patrick White’s1964 “Riders in the Chariot” – Patrick wrote “I am anxious to see the cover of the Penguin Riders in the Chariot which I am told is excellent in every way”30 – and she formed the backdrop to a famous Axel Poignant photograph of Sidney in his studio. The photograph appeared prolifically in newspapers, books and catalogues and now resides in the National Portrait Gallery of Australia.

No other painting better represented Sidney Nolan of the 1960s, or the complex layers of the Adelaide Ladies. Vermeer himself was represented by female portraits. They ranged from wealthy nobles in stately houses to simple country milkmaids. Many wore hats or linen caps and looked out of the paintings half turned, suggesting movement without the need for specific gestures or facial expressions, preserving the essential stillness of the compositions.

Detail of ‘Girl Interrupted at her Music’ (1658-59) by Johannes Vermeer

Although similarly half turned Lady Interrupted-like poses are apparent in many of Vermeer’s works, the echoes of his ‘Girl interrupted at her music’ are unmistakable here. The angle of the head, the back of the chair, the falling of the light, the shape of the body and instead of the simple linen shawl the flower festooned “seaweed mop like hat…covered with lollies” perfectly mirroring the Dutch work. And in a Nolan flourish that creeps throughout the series, the work itself appears ‘unfinished’. White primer board shows through as though Sidney himself has been interrupted. The same theme reappears in the Axel Poignant photograph, as Sidney stands almost humorously to one side wearing a paint-spattered apron as if interrupted mid-work.

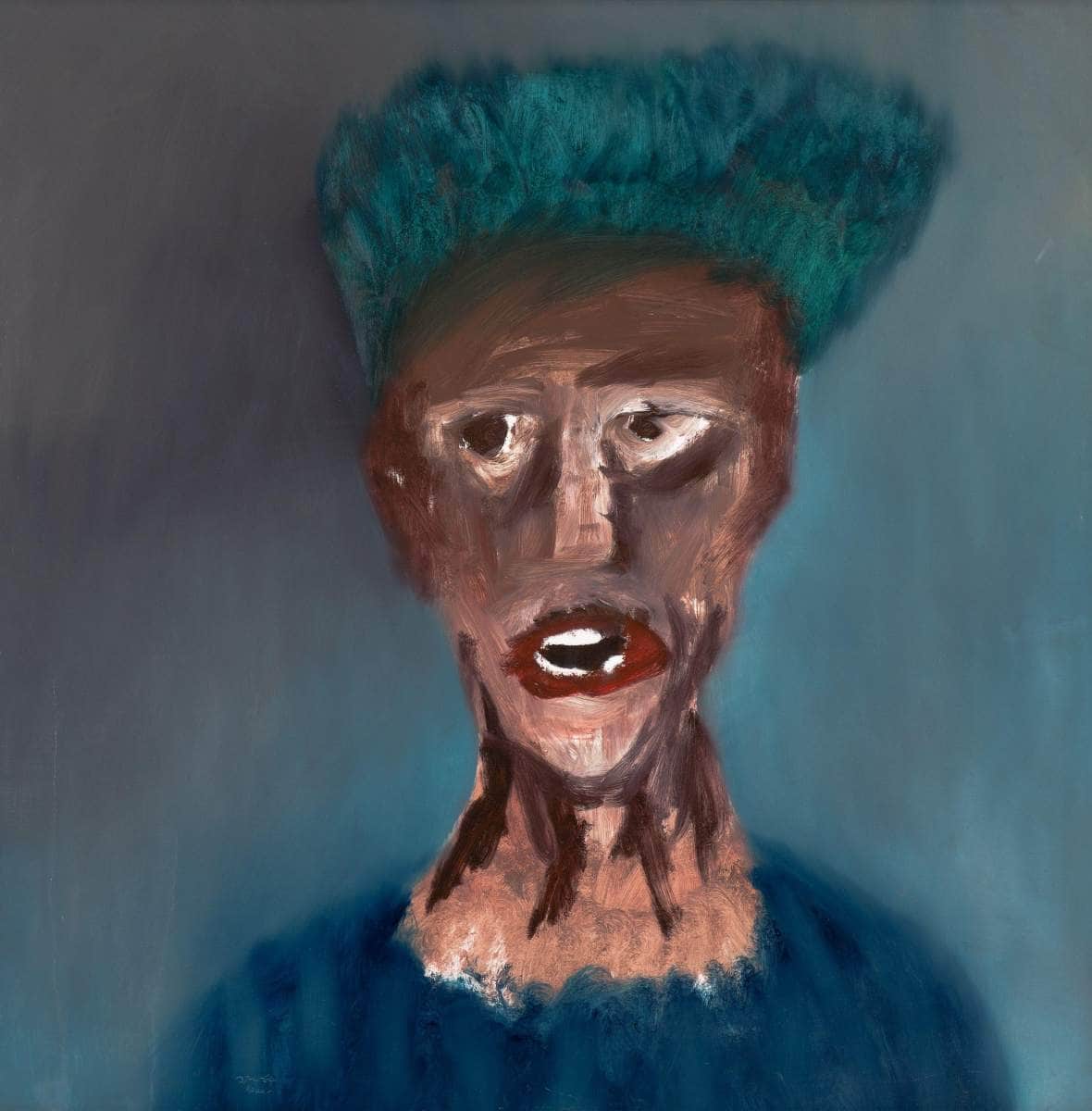

By May 28th the subtleties of light and shadow had been left behind and Sidney’s ‘Country Woman’ and ‘Woman with tree’ were blazing Nolan Australiana through and through.

‘Country Woman’ (28 May1964) by Sidney Nolan

There were several reasons for this mercurial detour back through ‘Kelly Country’ to revisit the theme of the persecuted outsider. The most obvious was that geographically Sidney was painting his way through the faces and places of his journey, from Sydney to the Adelaide Festival, but in reverse. Central Victoria, with the ghost of Ned, was the stop between the western Victorian faces of Dimboola with “… steak and eggs at the Greek café”31 before his northern dash to capture the “Urban women of Sydney”.32

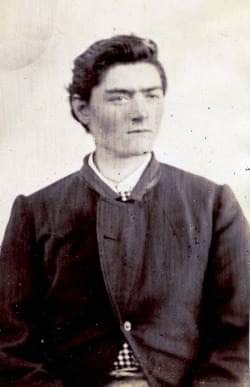

The Bushranger was also foremost in his thoughts for another reason. Sidney knew that in a few short weeks he would see his emotion charged, and now world famous,1946-47 Ned Kelly paintings once again. It would be the first time since he had painted, then abandoned them, 17 years previously when he stormed out on both the works and his tempestuous relationship with Sunday and John Reed.

In May 1964 Sidney was in constant communication with Alan Moorehead. He had travelled to Antarctica and Adelaide with him earlier in the year and he was now writing the introduction to the Thames and Hudson book accompanying the June Kelly exhibition at the London Qantas Gallery.33 In a clear expression of the high emotion Sidney felt at the time, he agreed to help hang the “Kellys” but expressly banned John Reed from accompanying the exhibition.

The third reason was that Sidney himself was feeling like the outsider on this day. In a letter to Albert Tucker postmarked 28th May he had this to say: “The whole art game seems to be based on misunderstandings. These are not the exception but the daily food of writers on art. I see little hope now of anyone ever arising in Australia who will write about its painters properly. Just as there was no inland sea to discover, so it seems there is no critical voice to discover”.34 This shot was aimed at Robert Hughes, an Australian art historian and critic, who in February 1964 had published an article on Tucker and who dogged Nolan with his criticism for many years. In his opening salvo three years previously Hughes had said “there is a forced repetitiousness in the later Kellys of 1954–57, a confused slickness in the rainforest paintings…and the neat thumbprint of Bond Street on Leda”.35

Sidney’s disdain for the art establishment can be felt in the narrow-necked, burnt umber and purple shadowed portrait bearing a disturbing resemblance to an 1873 prison portrait of Ned Kelly.36 With her hands clawed in a kangaroo-like pose ‘Country Woman’ is in, and of, a dream-like and heat-hazed country. She is a social outsider among the Ladies, framed by a distant, clouded horizon line reminiscent of Sidney’s famous Kelly-like silhouettes.

Ned Kelly (dated to June1873) photograph attributed to Charles Nettleton. Taken after his transfer to Pentridge Gaol in Melbourne aged 15 years

Art critic Daniel Thomas even made comparisons between Kelly and the Ladies during the1967 Nolan retrospective. He wrote “…as well as Kelly’s helmet- masks, we find the suburban ladies of Adelaide masking themselves quite well with no more than a hat, some make-up and a careful expression”.37

With all her adornments stripped away, ‘Country Woman’ is far from the streets of Adelaide. A modern image of the country but “not masked as I had painted Ned Kelly”38, she sharply reflects the rancor Sidney gave voice to that day.

Perhaps it was this aversion to critics on 28th May that bled over to May 30th and resulted in a Rembrandt portrait embedded in the series. Both men had led their artistic lives with a disregard for established rules resulting, at times, in severe criticism by art theorists.

Sidney’s passionate rant to Albert Tucker emphasises how critics often played the villain in his story – speed of output, lack of classical or formal training and his facility of image often led to critical censure. So too for Rembrandt. When asked for advice in 1670, the Flemish painter Abraham Breughel wrote a letter to Sicilian collector Antonio Ruffo full of contempt for Rembrandt saying that Italian masters would not condescend to paint the trifles Rembrandt splashed on canvas. Joachim von Sandrart, the German Baroque art historian implied in 1675 that Rembrandt was not only ignorant of the classical art canon but virtually illiterate. And17th century Dutch art biographer Arnold Houbraken wrote that Rembrandt was greedy, accepting so many commissions and working so fast that his pictures looked as though the paint had been smeared on with a trowel.

‘Self portrait wearing a soft cap’ (1631) etching by Rembrandt van Rijn.

It is possible that as the Ladies played out, the bond between the old master and the new wave modernist had grown so strong that it was simply impossible for Sidney to resist painting Rembrandt.

Just three years earlier, an English born novelist and journalist, Colin MacInnes, wrote that Sidney’s “rich pictorial language fed on all sights – on paintings on colour, photography and most of all on those of life – expressing his ideas in fluent shapes and vivid colours”.39 Kenneth Clark’s book began with the premise that the world, life itself and art inextricably entangled, were Rembrandt’s sources of inspiration – on one hand inspired by the visible world and on the other by existing forms of artistic creation reworked.40

Neither Sidney nor Rembrandt were interested in perfection and both strove to find alternate visual solutions. This quote describing Rembrandt, equally describes Sidney – “The succession of paintings point to a restless searching. Each picture, every version of the same picture, represents a new experiment, referring back and looking forward with new qualities coming to light. The great abundance of freehand drawings provides evidence of unrestrained creative powers allowing no submission to any step by step process”.41

‘Self portrait with cap pulled forward’ (c.1630) etching by Rembrandt van Rijn

The influence Rembrandt had on the series gave his appearance something of an air of inevitability. Whether there was one reason or many, Sidney adapted Rembrandt’s ‘Self portrait with a cap pulled forward’ (c.1631) for his own use on May 30th, and described it simply in his diary as ‘red brick background, smudged face, white loose hat’. Rembrandt’s self portraits were famous for his often rumpled hat and expressive eyes, but this painting is the only work in the series without eyes, removing the observational act, the famous gaze, and obscuring its true identity. Sidney turned the “angry young man” who Kenneth Clark assumed appeared in Rembrandt’s early etchings into the “Everyman”.42 Or in this case the “Everywoman”.

‘Sydney Woman white loose hat’ (30 May1964) by Sidney Nolan

Sidney worked solidly on the Ladies through the London spring, which had been cold, wet, dull and sunless. Temperatures averaged a miserable 5 ̊C in March, 9 ̊C in April and May followed suit. Suddenly in the last days of May, the temperature shot up to nearly 25 ̊C and, still in the throes of Rembrandt, Sidney turned to flowers and the change of season.

‘Saskia as Flora’ (1634) by Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt had repeatedly painted his wife Saskia as Flora,43 the Roman goddess of flowers and spring, and for the last time in the series Sidney appropriated pictorial ideas of a predecessor. On June 2nd 1964, three days before the anniversary of her 1633 betrothal to Rembrandt, Saskia was twice more wreathed in flowers.

‘Woman white flower crown’ (possibly 2 June 1964) by Sidney Nolan.

It was no coincidence that Kenneth Clark, during his tenure as Director of the National Gallery, greatly expanded the collections, acquiring many masterpieces. One of the best known was ‘Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume’ otherwise known as ‘Saskia as Flora’ (1635) by Rembrandt van Rijn.

Finally, on the 11th of June 1964, a veil was lowered on the end-to-end series, and Sidney’s last head was dated.

His simple style with complex undertones was well suited to the nature of a portrait and the spirit of a face. International literary icons agreed.

‘Lady Interrupted’ on the cover of Patrick White’s ‘Riders in the Chariot’ published by Penguin Books in 1964 and subsequently on the cover of repeat publishings in 1974, 1976 1979 and 1985

Patrick White was enthusiastic about ‘Lady Interrupted’ appearing globally on the cover of ‘Riders in the Chariot’ and although less enthusiastic about the group of four portraits – including ‘Suburb’ and ‘Country Woman’ – used for the UK release of ‘The Burnt Ones’, he still wrote “I think the jacket is marvellous as itself, but I can’t feel it has a great connection with the contents of the book. Still, it is so arresting I am sure it will sell a great many copies”.44

Sidney Nolan and Patrick White, Adelaide Arts Festival (1964) by Robert McFarlane

Charles Osborne, an Australian journalist, theatre and opera critic, poet, novelist and director of the Arts Council of Great Britain also recognised the potency of the images. He was there at the beginning in Sidney’s first diary entry, and there at the end for their last major showing as a group. In the summer of 1972, eight Ladies reportedly accompanied readings at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, as part of Poetry International directed by Osborne45, and a good number of them passed into his own collection in the same year as Cynthia Nolan’s death.

A group of Sidney’s Ladies also appeared at the opening of the Marlborough-Gerson Gallery in New York in January1965, but the critics’ praise was saved for the well-worn Kelly and new Antarctic images. What they didn’t realise was that Sidney had started on the ice in early April 1964, but stopped after three rather thinly scumbled works and one thickly oiled scene, turning his attention instead to the Adelaide Ladies. The Ladies led to his May 30th discovery of Rowney’s gel, which became an important medium for the subsequent 59 rich and liquid Antarctic works.46 That was two days after finishing ‘Country Woman’ and the same day he painted ‘Sydney urban woman white loose hat’.

Three days later, on June 2nd, he wrote to his friend and Antarctic travelling companion, author Alan Moorehead saying “Just coming to the end of a long line of women’s faces based on those I saw in Adelaide. Already Antarctic colours are creeping into their hats and dresses…I think I am about ready to start on the ice”.47

The response to the Adelaide Ladies was different in Australia. When they appeared with the new Kelly paintings and landscapes at the David Jones Gallery in Sydney on 5th May1965, the Sydney Morning Herald art reviewer applauded, saying that the six heads on show formed a “more fluent, lively and colourful departure from the more sombre landscapes” and added “there are still undertones of depths that reach through and beyond the immediate impressions”.48

Despite being of mixed parentage – conceived in Adelaide during the opening of his African exhibition, created in London and infused with the colours of Antarctica – Nolan’s deft touch had nationalised bitter, optimistic and even cosmic themes in his Ladies.

For all their size, they were full of expressive depths. For all their stillness, they were full of life and the spirit of the country. The monumental simplicity of the portraits blinded many critics to the artistic, tragic and heroic identities hidden within. Many of their secrets have been forgotten, but they should always be remembered as a master painter’s response to the face of contemporary Australia in the 1960s.

EDITOR’S NOTE

At this point in the book five chapters then divide the 59 paintings chronologically and thematically, and provide comprehensive details and illustrations of each. These chapters, as follows, will in due course be posted on aCOMMENT with links appearing here:

27 April to 12 May 1964 – From English soil and Adelaide

12 May 1964 – The shadow of the masters

12 May to 28 May 1964 – A window on the Wimmera

28 May 1964 – Back through Kelly country

30 May to 11 June 1964 – The end of the road

Epilogue THE FINAL WORD

Sidney Nolan and Ladies in his Putney studio 1964

Critics and curators alike have all but ignored the Adelaide Ladies, unsure how they “fit” into Sidney’s oeuvre. Like Mrs Colquhon and Mrs Sugden, they looked to the subject matter for reassurance, but in ones or twos the faces are difficult to read.

Alone, the paintings lack the attributes that make them heroic or mythic figures. They do not represent a ‘noble spirit’ and as portraits they are not defined by action or purpose. As a group we know their spirit was shaped, and sometimes crushed, by environmental and social pressures outside of their control.

What the critics struggled to see in single images but what we see in the many, are the classic characteristics defining an anti-hero.

Sidney pinpointed a time in modern society and a role that only women could own. A role based on an imported English class consciousness as Australian women were either hemmed into small pockets or isolated and strewn across a wide brown land. It was a time in Australia when a war-footing economy with women in the factories and working on the land was still fresh in the communal memory, yet publicans would be fined if they served a woman in a public bar.

It was these paradoxes that triggered the painter’s response in Sidney. As close friend and author Elwyn Lynn wrote, “the constant and curious correlations between cultures and the contrarieties, ironic and diverting, between customs, inspire his attitudes”.49

Sidney valued his Ladies as much for their failings as their successes and the pictures are at times “disturbing because he is an observer of the awkward as opposed to the comfortingly familiar”.50 Unforgiving in his approach, he captured their connected and disconnected character, what he called their “tawdry nature”, but at the same time he considered them portraits of defiance – of the land, the old ways, the new ways and possibly even their destiny.

This series comprehensively explores the ‘outsider‘. What has confused the critics is that Sidney explores this theme in general archetypal terms, rather than through specific or literal imagery.

1964 was Sidney’s year of the ‘outsider’. Fresh travel experiences reinvigorated his art and with “an often disconcerting momentum which revealed flashes of sheer genius. Inventiveness, lyricism, and a strong sense of the theatrical…”51 he painted manically, creating four sets of work strongly interrelating the identity of Australia.

In January Sidney had travelled to Antarctica with Allen Moorehead, in February drove overland between Sydney and Adelaide, returning from the Adelaide Festival in March better versed in Australian landscapes and faces than ever before. He painted Adelaide Ladies from April to June (at least 59 paintings in 46 days), Burke and Wills in August, Antarctica from late August through to late September (also 59 works but this time in 27 days) and from October to December Ned Kelly – “I did a number of such paintings, probably 25 leading up to Riverbend”.52

Sidney encouraged people to compare the four sets of works – his Adelaide Ladies, Burke and Wills, Antarctica and Ned Kelly – by exhibiting them together: from the Adelaide Ladies as the ‘heart’ of the country in their own cultural and physical wilderness, through Burke and Wills in the ‘dead heart’, Antarctica as its own icy desert, and the lonely watery wastelands inhabited by Ned Kelly.

For the January 1965 opening of the Marlborough- Gerson Gallery in New York, Sidney chose to show an equal number of paintings side by side – ten of the Adelaide Ladies (including ‘Stockman’), ten of the new Burke and Wills pictures, eleven Antarctic landscapes and twelve new pictures of Ned Kelly.53

He knew that when the paintings were shown in isolation they created an episodic narrative at best – being disconnected works and snapshots, when in fact each series (and the years’ work) was created as one continuous story in paint.

Beyond 1965, recognition of the Adelaide Ladies was limited. They appeared in dribs and drabs at major exhibitions and retrospectives, out of context as singular compositions rather than part of Sidney’s thematic pathway. Art critic Daniel Thomas considered the context of the1964 works best. In1967, he described them as “Recent explorers on camels travel over melting landscapes. Antarctic ice deserts heave”54 and then went further in1973 writing “Like Nolan’s portraits of Antarctic or desert explorers or like Adelaide’s middle class masked by make-up and flowered hats, there are richly ambiguous images at once heroic and squalid… he thinks he is exploring the unique qualities of our own Australian soul, and he may be right.”55

In hindsight it is a shame that the Ladies were not included in later retrospectives.

In the 1987–1988 ‘Landscape and Legends’ retrospective exhibition they would have represented both the social landscape and the narrative of the outsider with faces drawn directly from memory of his 1964 experiences. At the 2007 ‘Sidney Nolan’ retrospective their construction would have been the epitome of the Rimbaudian influence the exhibition represented, “the process of living and working at speed, and submitting himself compulsively to the day”.56 The Ladies were created in the same way Rimbaud himself created. Rimbaud was described by French writer and close friend Ernest Delahaye as “A passionate believer in observation, he prefers to make use of the real, of things he has experienced, but then displacing them from their true context, splitting them into parts that can be used in a new way, joining and mingling things which are in fact quite separate”57 – paintings, photography and memories of life itself, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Sunday Reed, Dimboola, Antarctica, Ned Kelly, soldiers and explorers.

“For Sidney Nolan, creating art was about more than dabbing paint on canvas. It was about digging deep into the red dirt of Australia, and into the soul of those who have lived and died here”.58

I like to think of Sidney standing in front of the Adelaide Ladies looking at his story, and history looking back at him.

IMAGE CREDITS

All images of Sidney Nolan paintings are © The Sidney Nolan Trust / Bridgeman Art Gallery.

The bigger picture

Sidney Nolan in front of his painting for the jacket of the 1964 edition of Patrick White’s ‘Riders in the Chariot’,1964, by Axel Poignant © Roslyn Poignant. Image source National Portrait Gallery, Canberra digitised collection.

Meet the ladies

Sidney at Bonython Gallery. Sidney Nolan and Robert Helpmann, Adelaide Arts Festival,1964 © Robert McFarlane. Courtesy Josef Lebovic Gallery & the National Library of Australia.

‘Self-portrait with Saskia’ (1636) etching by Rembrandt van Rijn. Etching 10.5 × 9.6 cm (plate) 10.9 × 9.9 cm (sheet), 3rd of 3 states National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1933 (14-4) Image courtesy the National Gallery of Victoria.

‘Mrs South Kensington’ (1937) by William Dobell © Sir William Dobell Art Foundation. Image source AGNSW digitised collection.

‘Girl Interrupted at her Music’ (1658-59) by Johannes Vermeer. © The Frick Collection New York.

‘Ned Kelly’ (dated to Jun1873) photograph attributed to Charles Nettleton. Image source National Museum of Australia digitised collection.

‘Rembrandt wearing a soft cap: full-face; head only’ (c.1631), etching 5.0 x 4.4 cm (plate) 5.5 x 4.8 cm (sheet) B./Holl. 2 only state National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Everard Studley Miller Bequest,1961 (1239-5). Image courtesy the National Gallery of Victoria.

‘Self portrait with cap pulled forward’ (c.1630) etching by Rembrandt van Rijn. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Scan created by Reba Fishman Snyder.

‘Saskia as Flora’ (1634) by Rembrandt van Rijn. © the Hermitage Museum St Petersburg.

Sidney Nolan and Patrick White, Adelaide Arts Festival1964, by Robert McFarlane © Robert McFarlane. Courtesy Josef Lebovic Gallery & the National Library of Australia.

The final word

Sidney Nolan and Ladies in his Putney studio 1964. ABC documentary Nolan, 2018

PUBLICATION

© Andrew Turley 2016. All rights reserved. This document is copyright.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this

publication may be reproduced without permission in writing from the

author. Neither may documentation be stored electronically in any form or

by any means, without the prior written permission of the author.

This document has been created solely for the purpose of promoting and

facilitating education and research.

Author: Andrew Turley

Editing: Harriet Richert

Book design: Savit Pookapun

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Sidney Nolan images are © The Sidney Nolan Trust / Bridgeman Art Gallery.

For all other copyright and image acknowledgements see Copyright and

Credits above.

ISBN 978-0-646-59749-2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Mark Fraser was the first Director of MONA in Hobart and is now Chairman of Bonhams Australia. He is also the most knowledgeable and passionate ‘Nolan man’ I know. The first person I met committed to ‘feeling’ Sidney’s art as an expression of both the head and heart. Without our conversations or his insight and encouragement the soul of the ladies might still be buried.

Harriet Richert was the first to persuade me to write the story of Sidney’s Ladies, to continue writing it when I faltered, and to do it in a way that stayed faithful to the spirit and character of the paintings. It was her challenging, pushing and polishing that kept the words grounded in Sidney’s 1964 and helped side step the distractions of better known but well-trodden narratives.

Rachael Ash was the first to introduce me to Sidney Nolan. Five years ago

we knew very little about him. When mesmerised by a particular work from ‘African Journey’ she triggered our own Nolan journey – both in words and across the globe to Kisoro in Uganda and Harar in Ethiopia – and somehow she continues to connect intuitively with paintings that later reveal hidden histories or turn out to be works particularly favoured by Sidney himself.

END NOTES

- Extract from ABC Guest of Honour to air 22/3/1964. ‘Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words’, edited Nancy Underhill, Penguin Group Australia, 2007 p.309.

- John Macdonald unpublished interview1992 from Lou Klepac ‘Nolan, Ripolin and the act of painting’ in ‘Sidney Nolan’, Beagle Press for AGNSW, Sydney 2008 p.83.

- Sidney Nolan quoted by Noel Barber, ‘Conversations with painters’, Collins, London 1964 p.94.

- Ibid p.98.

- Terence Maloon in the Sydney Morning Herald 8th Jan1983.

- Barber, Op.cit. p.94.

- This number is based on fifty four works in private collections dated or with provenance, four in public institutions in Australia and one held at the Tate Gallery, London.

- Simon Pierse, ‘Australian Art and Artists in London1950-1965; an antipodean summer’, Ashgate Publishing, Surrey, England, 2012 p.48.

- Ibid p.241.

- Marr. D, ‘Patrick White: a life’, Random House, NSW,1991 p.375.

- White. P, ‘Riders in the Chariot’, Penguin Books, England 1964 p.479.

- W.T. ‘Nolan Paintings at David Jones’ Art Exhibition Reviews, SMH 5th May1965 p.14.

- Letter to Cynthia Nolan from Adelaide on13 March1964 from ‘Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words’, edited Nancy Underhill, Penguin Group Australia, 2007 p.186.

- Tate catalogue entry for T03554 Woman in a Hat c.1964 “Nolan says that he was thinking more of Australian country women with their ‘dried, sad look’, who get dressed up to come into town for country agricultural shows and the like”.

- Nolan said “Its very different from being a European or American. There is a certain innocence about being an Australian. It’s about being part of a dream that hasn’t yet been shattered…I’m reluctant to drop the concept of a hero figure. If I lost this I would be discarding something very Australian. Without the hero you end up with anonymity… but on this visit, when I travelled across the country with Drysdale, I was fascinated by truly Australian faces. I found myself looking at them for the first time and I wanted to paint them not masked as I had painted Ned Kelly” from Charles Spencer, ‘Myth and Hero in the Painting of Sidney Nolan’ Art and Australia, September 1965.

- Rodney James, ‘Sidney Nolan: Antarctic Journey’, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery 2006 p.10.

- Diary entry 26 April 1964 from ‘Nolan on Nolan’, edited by Nancy Underhill, Viking, Australia 2007 p.28.

- Daniel Thomas, ‘The poetic themes of Sidney Nolan’ SMH, Saturday Sep 9th1967, p.15.

- Lou Klepac ‘Nolan, Ripolin and the act of painting’ in ‘Sidney Nolan’, Beagle Press for AGNSW, Sydney 2008 p.83. In a 1964 interview as ABC guest of honour during the Adelaide Festival he also said “In these notes I have access to my own thoughts in a way that I have not got in the sketches or drawings I show publicly. These written things for me are always the key to the scene when I was first looking at it”.

- Nolan said of an Australian attitude “it seems like they’ve got to act like Anglo-Saxons; that is their culture, that’s what they inherited. They’ve got Keats and Shakespeare; that’s what they’ve been taught at school and that’s what they’ve got to deal with as much as possible…they tend to come back to what they know, what came out of the ships” during ‘Bewitched by the Environment – The Australian Painter Sidney Nolan talks to A. Alvarez via BBC 1’ The Listener, 13 November 1969.

- Barry Pearce, ‘Nolan’s Parallel Universe’ in ‘Sidney Nolan’, Beagle Press for AGNSW, Sydney 2008 p.57.

- Scott Bevan, ‘Bill: The Life of William Dobell’, Simon & Schuster Australia 2014.

- James Gleeson ‘William Dobell’, Thames and Hudson, London 1964, p.48.

- Tate catalogue entry Op.cit.

- Sidney Nolan diary record dated 27th April 1964 from Rodney James ‘Sidney Nolan: Antarctic Journey’ Mornington Peninsular Regional Gallery, 2006 p.17.

- Kenneth Clark’s introduction in ‘Sidney Nolan’ Thames and Hudson, London 1961 p. 9.

- Interview by Peter Fuller ‘Sidney Nolan and the decline of the West’ Modern Painters Vol no.2 Summer 1988.

- T03554 Woman in a Hat c.1964 Oil on hardboard 48 × 48 (1219 × 1219) not inscribed presented by Lord McAlpine 1983. Published in: ‘The Tate Gallery 1982-84: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions’, London 1986.

- Brian Adams, ‘Sidney Nolan’s Odyssey: A Life’ p.175.

- David Marr (ed.), ‘Patrick White: Letters’, Chicago University Press, Chicago, 1996 p.270-71.

- Letter to Cynthia Nolan 24th February1964 written in Western Victoria on the way to the Adelaide festival ‘Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words’, edited Nancy Underhill, Viking, Australia, 2007 p.185.

- James, Op.cit p.21 “Paint 5 4×4 paintings for the first time using Rowney’s Gel. Sydney ‘urban’ women”.

- Letter to Alan Moorehed from Sidney Nolan 20 May1964 “Thames and Hudson have asked me to write to you…What is desired apparently is a longer piece from you, 600 words or so, with the emphasis on Kelly and not on myself… I think there is a great deal you could do for Kelly” from ‘Nolan on Nolan’, edited by Nancy Underhill, Penguin Group, Australia 2007 p. 216.

- Patrick McCaughey, ‘Bert & Ned: The correspondence of Albert Tucker and Sydney Nolan’, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Victoria 2006 p.233.

- ‘Sidney Nolan’ Thames & Hudson Reviewed by Robert Hughes in Australian Book review Vol.1 no.11961.

- Photograph of Ned Kelly, attributed to Charles Nettleton, which was pasted to Ned Kelly’s criminal record. The caption states the photograph was taken five months after Kelly was transferred to Pentridge in Melbourne from a country jail, dated to June 1873.

- Daniel Thomas, ‘The poetic themes of Sidney Nolan’ SMH, Saturday Sep 9th 1967, p.15. In 1972 Daniel Thomas continued the metaphor when he reviewed Sidney Nolan’s exhibition of portraits of ‘Miners’ and said of them “…like Adelaide middle-class, masked by make-up and flowered hats, these are richly ambiguous images at once both heroic and squalid” from ‘Heroism, squalor in Nolan faces’, Entertainment and the Arts, SMH 8th November1973 p.4.

- Spencer Op.cit 1965.

- Colin McInness in ‘Sidney Nolan’ Thames and Hudson, London 1961 p.35.

- Vitale Bloch, ‘Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance’, The Literature of Art, Burlington Magazine Vol.109 no.777 (Dec. 1967), p.714-716.

- Michael Brockemuhl, ‘Rembrandt’, Taschen, Koln 2014, p.8.

- Kenneth Clark, ‘An introduction to Rembrandt’, London, 1978 p.14.

- Simon Schama ‘Rembrandt’s Eyes’ Penguin London1999 p.367-369.

- Marr. Op.cit p.270.

- Eight works from the series (including ‘Suburb’) were auctioned by Sotheby’s Australia in Sydney on 29/11/1993 under the title “Property from the collection of Charles Osborne London” and noted “Although painted at different times (works were dated from 27/4/1964 to 18/5/1964) these eight female portrait heads were assembled by Sidney Nolan to be exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Arts London, in the summer of 1972, as part of the Poetry International directed by Patrick Garland and Charles Osborne. The paintings formed a visual accompaniment to a reading, by Edward Woodward and Vivian Merchant”. Notes from the AGNSW library state that one of the works sold by Sotheby’s as part of that Charles Osborne collection, ‘Interior’, was in the possession of Cynthia Nolan up until 1976 – the year of her death.

- Sidney Nolan diary note “Used Rowneys gel for the first time. (a) Girl with roses crimson painting, (b) red-brick background smudged face white loose hat, (c) violet and vermillion face, (d) pocked mark face, e. ditto”.

- Letter to Alan Moorehead from Sidney Nolan 02 June1964 from ‘Nolan on Nolan’, edited by Nancy Underhill, Penguin Group, Australia 2007 p.217.

- ‘Nolan Paintings at David Jones’ SMH Op.cit. On May16th 1965 in the ‘Sydney Town’ section of the SMH was “Five pictures have been sold from the Sidney Nolan Exhibition at the David Jones Gallery – three landscapes for 2,000 guineas each and 2 heads for 1,500 guineas each. All buyers were from overseas”. One of the heads purchased was the work now in the Tate collection.

- Elwyn Lynn ’Sidney Nolan – Australia’ Bay Books,1979 p.19.

- Elwyn Lynn Op.cit p.14.

- Barry Pearce, ‘Sidney Nolan. A new retrospective’ Curator of the exhibition, 2007 AGNSW Archives.

- Sidney Nolan quoted by Elwyn Lynn, ‘Sidney Nolan – Australia’, Bay Books,1979 p.130.

- Catalogue ‘Sidney Nolan’, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery Inc, New York, Jan 1965.

- Daniel Thomas, ‘The poetic themes of Sidney Nolan’ Sydney Morning Herald, 1967.

- Daniel Thomas, ‘Heroism, squalor in Nolan faces’ Sydney Morning Herald, Nov 8th 1973.

- Barry Pearce, ‘A Journey With Sidney Nolan’ Nelson Meeres foundation.

- Charles Nicholl, ‘Somebody Else: Arthur Rimbaud in Africa’ Random House, London1997, p.152.

- Scott Bevan ‘Exhibition celebrates work of Sidney Nolan’ on The 7.30 Report, Australian Broadcasting Corporation broadcast 31/10/2007.