Based on the story of 1940s Heide, Philippe Mora’s recent film “Absolutely Modern” tells of Modernism, the female muse and the role of sexuality in Art.

The Muse. Photo from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

“We know that certain minds can create an order in the chaos of appearances which other minds can contemplate with delight. We know that certain eyes can see in nature shapes and colours to which our eyes were blind”. So wrote Sir Kenneth Clark in his 1945 essay Art and Democracy just before he vacated his directorship of the National Gallery.

Four years later, perhaps in search of such minds and eyes, he visited Australia – where he would find them in a tiny bungalow in Woniora Avenue, Wahroonga. They belonged to Sidney Nolan.

Then, 25 years later, K, as Clark was known to his friends, would enter the homes of millions via his popular TV series Civilisation, and lift the scales from many blind eyes so they too could contemplate these delights.

Lord Steinway’s “Epic of Civilisation”. Photo from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

Now, almost 70 years letter, is he here again?

Not quite. But Lord Steinway, aka Philippe Mora, is here. Along with the real Orson Welles, the real Ern Malley, and some not quite so real (but quite surreal) players on the 1940s Heide stage: John and Sunday Reed, Joy Hester, Albert Tucker, and Nolan; and also Mora’s very real mother Mirka who stars as herself – close friend to the Reeds, to Hester and Tucker, and captive to the seductive handshake of Nolan whose hands, she confides, “were like a novel.”

The vehicle for this improbable collage of characters is Philippe Mora’s recent film Absolutely Modern. And it is absolutely must-see – not only for the coterie of Heide aficionados , but for all those willing to be drawn into a unique avant garde filmic experience; one perhaps not unlike first seeing Nolan’s Kellys and Tucker’s Images of Modern Evil with 1940s Melbournian eyes.

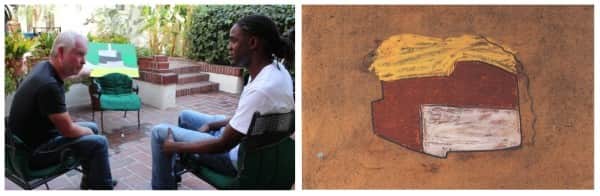

An unknown and unsuspected son materialises (is it Steinway’s son or Mora’s?) He is dark, from Surinam, and in search of his father. Mora (or is it Steinway?) will teach him culture, he will teach them soccer. In this they chose well for Mario Melchiot, who plays young Jack Steinway, was capped for Netherlands more than 20 times. He is something of a natural thespian to boot. Why not have him play both Bert Tucker and Sid Nolan in their film: Tucker as he begs Joy Hester not to give their son Sweeney (played by one of Mirka’s heady dolls) to the Reeds, and Nolan as he resists Sunday Reed’s plaintive wailing “Don’t leave me Sid.”

Jack Steinway plays Nolan and Tucker. Photos from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

A deft touch – not for the first time is a dark figure placed in the landscape of the antipodean avant garde.

The story of 1940s Heide is well known: Nolan and the Reeds in their ménage à trois, creation of the Kellys, Nolan’s departure, and his seemingly lifelong attempts to banish his disquieting muse and shed this Heide albatross; attempts characterised by Paradise Garden, his illustrated book of vituperative poems.

Less well known is that a Paradise Garden film was made in the early 1970s with the poems recited by Orson Welles. Both film and soundtrack were believed lost.

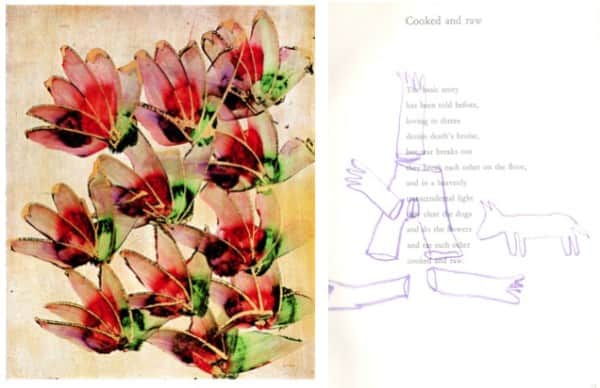

Not so! For any steeped in the Sid/Sun saga, Absolutely Modern would be well worth viewing for its pre-title voice over alone – the distinctive Orsonian tones recite Nolan’s Cooked and Raw in what is the first public release of this Welles performance. Click here to listen to Cooked and Raw

Sidney Nolan’s “Cooked and Raw” from “Paradise Garden” 1972

“Tragical-comical-historical-pastoral” is the how Shakespeare’s Polonius describes plays performed by the troupe of players visiting Elsinore. Replace pastoral with satirical, and you are absolutely modern.

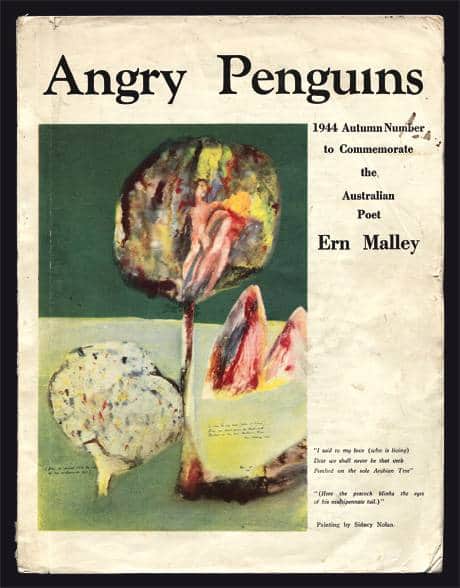

Tragical. The 40 year long dénouement of the relationship between Nolan and Sunday Reed has all the elements of tragedy. It certainly blighted the lives of both. They would, in the words of Ern Malley, and as they themselves felt when discussing how uncannily relevant the hoax poems were to their own circumstances, “never be that verb perched on the sole Arabian Tree.”

Sidney Nolan, Arabian Tree, 1943

Cover of Angry Penguins, No 6, June 1944

Moving beyond them, the film is dedicated to Sweeney Reed, the closest friend of Philippe Mora’s youth, whom he filmed – crucified in the construction site of the new Heide – in his earliest works.

Sweeney

Like the Mora/Steinway son Jack, Sweeney also sought a father. And a mother. Adopted by the Reeds, he led a privileged but troubled life and suicided in 1979. As did John Reed in 1981. And as did Sunday Reed 10 days later. Sweeney’s life and death profoundly affected all, and his presence lingers still – a sad reminder, to misquote Omar Khayyam, of a wilderness ne’er paradise enow.

Comical. Some may recall the goo-goo-googley eyes of Barney Google and Eddy Cantor.

Steinway researches pornography. Photo from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

They are a match for those of Lord Steinway as he gazes up at Marilyn Monroe’s panties beneath Seward Johnson’s 8 metre Forever Marilyn statue in Palm Springs. With similar perspective and greater bewilderment he also surveys the bollocking wonders of the LACMA Bourdelle sculpture Hercules, the Archer.

Steinway researches sculpture. Photos from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

Apart from visual humour, there is a definite comic element even though some of it might best be appreciated by the cognoscenti. Thus a wry smile will reward those familiar with Nolan’s Head of Rimbaud as the faux John Reed argues “It’s not a cake.” Neither, with apologies to Adrian Lawler, is it a French cheese.

(L) “That’s not a cake” John Reed meets Nolan. Photo from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora; (R) Sidney Nolan, “Head of Rimbaud”, 1938-1939, Heide Museum of Modern Art.

Historical. The film opens a window on an epoch making episode in the history of Australian modernism – a window admittedly Mora-tinted, but not tainted, and bringing with it an acuity of vision unblemished by prejudice from any personal experience of those heady Nolan-charged days of the 1940s, for when the Moras arrived in Australia from Europe, Heide had not seen Nolan for more than four years. Whilst the entire Mora family was very close to the Reeds – Mirka saying of Sunday “She needed me a lot. I spoiled her a lot. But I loved John and Sunday very much. They were family” – Nolan was not a topic for discussion. “That was a no no. Only Barrie Reid could discuss him.”

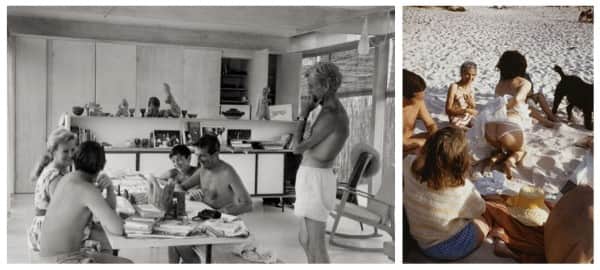

The Reeds and Moras at Aspendale. (L) Clockwise from bottom left: John Perceval, Nadine Amadio, Sunday Reed (above divider), Philippe Mora, Georges Mora, John Reed, photo by John Sinclair 1962; (R) Clockwise from bottom left: Sunday Reed, Georges Mora, Lucy Beck, Mirka Mora “showing her frilly knickers”, photo by Albert Tucker 1961.

The Moras thus experienced these Nolan times at one remove, and Absolutely Modern can be seen as correspondingly the more dispassionate.

Satirical. Nothing is sacrosanct when Mora unleashes Lord Steinway: not modernism itself, nor its temples such as Heide, nor its critics like Clark, certainly not its muses, and not the exercisers of this other craft or sullen art – whether Picasso, Man Ray or Nolan. His satire makes us think about what we laud and why. The take on the creation of Nolan’s Mrs Fraser painting is but one example.

Steinway explains Nolan’s “Mrs Fraser”. Photos from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

How to see it.

Absolutely Modern premiered last year at the New Horizons Film Festival in Poland and I saw the Australian premiere at the Arc, the theatre of the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra.

Films of the avant garde seldom see general release. Absolutely Modern is available from Amazon Instant Video via the following links.

Movie link:

Trailer link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RToly7cnsvA

Other reviews and background can be seen at the Facebook page for the film:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Absolutely-Modern/429822753746917?ref=br_tf

Lord Steinway (or is it Mora?) introduces the film saying “This is one of those sad stories that ended up making great art. And it turns out that much great art has misery and angst and tragedy behind it.” And that is apt summary.

Mora and Steinway go on to say “Let’s hope we can create some great art sometime, without all the sturm und drang and trauma.” And they succeed. Absolutely Modern is great art – at least this reviewer thinks so.

And that leads me to suggest how we might see it other than via Amazon. Why should not art such as this be packaged in limited editions for acquisition by major art institutions and collectors? And why should such institutions not make public screenings of such works in their theatres for their gallery Societies and their groups of Friends?

May this encourage Philippe Mora to contact our galleries to this end, and encourage you to see the film.

POSTSCRIPT.

The interviews with Mirka Mora are valuable in their own right. She paints a penetrating idiosyncratic picture of the Reeds, particularly Sunday. Philippe Mora has kindly agreed to provide aCOMMENT with Lord Steinway’s complete interview with Mirka for transcription. The transcript will be posted in due course.

Photo from “Absolutely Modern” Copyright P.Mora

3 Comments

Join the conversation and post a comment.

I couldn’t agree more with what you write about this film. I was transfixed and constantly amused all the way through.

And I am pleased to advise you that, like a lot of Philippe’s other film work, the film was acquired for the National Film and Sound Archive’s National Collection some time prior to its premier in Arc.

I’ve just stumbled onto this guy.? and the history. FFS.! Why this isn’t more widely known/celibrated.? So much junk on the net. This held me transfixed. Well done all.!

Thanks Peter